Lewis Hine caption: Dillon Mills, Dillon, S.C. Lizzie Davis, (smallest). Been in mill 2 years. Next–Nettie Arnet – Been in mill 8 years. Next–Monnie McCraney, been in mill 3 years. Next–Vater Arnet, been in mill 8 years. Next–Mattie Connor, spinners and Winders. Saturday, Dec. 5, 08. Location: Dillon, South Carolina.

“Following a meeting of the board of directors a few days ago, announcement is made that Mr. W. T. Bethea will succeed Mr. W. M. Hamer as president of the Dillon and Hamer Cotton Mills. Mr. Hamer voluntarily retires from the active management of the two mills to enjoy a well earned rest after performing the arduous duties of president for a period of ten years. Mr. Hamer is a large stockholder in both mills, and will retain his holdings in the two institutions. He will continue to act as president of the Maple Mill, which is twice as large as the older mills.”

“Notwithstanding the depression in the cotton goods market for the past several years, Mr. Hamer has managed to keep all three mills running, and recently the Hamer Mill has been equipped with new machinery, which brings its physical condition up to the highest point of efficiency. Dillon is the second largest cotton manufacturing county in Eastern Carolina, and the combined capital of its three mills is about $600,000.” -November 4, 1910 (two years after Hine took the photograph), The Sunday News, Dillon, South Carolina

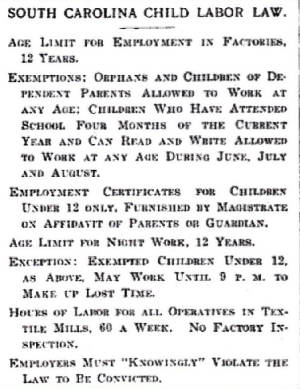

“COLUMBIA, S.C., Feb 7: The (South Carolina) House of Representatives, by a majority 18 today passed the Marshall bill prohibiting the labor of children under twelve years old in cotton mills. It had passed in the Senate by a large majority. The bill is to go into effect gradually. Children wholly dependent on their own labor for support, or having widowed mothers are partially exempt. None are to work between 7 P.M. and 7 A.M. Fine and imprisonment is provided for the employment of children under age, and punishment is also provided for parents who make false report of age of their children.” –New York Times, February 8, 1903 (five years before Hine took the photograph)

Lewis Hine had been taking photographs of child laborers for the National Child Labor Committee for about five months when he visited Dillon. He took 22 pictures, mostly of children that worked at the Maple Mill, and some that worked at the Dillon Mill, including the one above. He was apparently unable to get inside the mills, since all the pictures were taken outside. Hine was not happy with what he saw, as evidenced by the report below, which appeared in The Survey, Volume 21, published in April of 1909.

“In the town of Dillon, Mr. Hine heard many complaints among workmen about conditions in general – low wages, long hours, pressure of work, and use of young children. During the past year, some children have been turned off, but many remain, some under the guise of helping. The children themselves overstate their ages – their parents have misstated their ages so long. Illiteracy seems to prevail here. Many boys and women could not even spell their own names. The mill schoolhouse is a shed-like structure and very small. The mills were not running at night, but the men expected them to start up soon. In the Maple Mill at Dillon, one boy was found – a boy of ten – who had worked for three years and who is now earning thirty cents a day.”

I found the Arnette (not Arnet) sisters listed in the 1910, living in the Manning Township section of Dillon County. They were two of nine children born to Susan (Rowell) Arnette, now a widow. Three of the children were working in the cotton mills, including Nettie, but not Vater (Lavator is correct). A few minutes later, I found the family in the 1900 census, living in Green Sea, Horry County, South Carolina, about 35 miles southwest of Dillon. Her husband, William Wright Arnette, a farmer, was still living, and they had all of their nine children living with them. One of them, James, died before 1910.

In 1920, Susan was still living in Manning Township, and worked as a winder in a cotton mill. The only child living still living with her was Nettie, who had the same job. Both were listed as being illiterate. Ten years later, Nettie was listed in the 1930 census as a patient in South Carolina State Hospital, in Columbia, once known as the South Carolina Lunatic Asylum. She stated that she could read and write. She was listed again as a patient at the hospital in the 1940 census.

Nettie died in Columbia on April 15, 1975, at the age of 78, 79 or 80. Her date of birth is uncertain. The Social Security Death Index states July 2, 1895. In the 1900 census, it’s about 1897; in 1910, about 1895; in 1920, about 1897; and in 1930 and 1940, about 1895. South Carolina did not officially record births until 1913. So she was 11, 12, or 13 when Hine photographed her. The caption says that she had been working in the mill for eight years. That is surely a mistake, probably made by the National Child Labor Committee when they transcribed Hine’s caption, which was originally scribbled on a small notepad.

I could find no obituary, and I cannot request her death certificate unless I am a direct descendant. Since it appears that she did not marry or have children, no qualified descendants are living. Did she die in the State Hospital, or did she leave, get a job, and take residence in Columbia? I talked to several descendants of her sister Lavator (see her story following this), and they had never heard of Nettie. So the rest of Nettie’s life remains a mystery.

I found considerable information about Lavator Arnette on FindAGrave.com, and that helped me locate Lynn Abee, one of Lavator’s granddaughters. When I sent her the Hine photograph of her grandmother, she told me: “It was an ‘oh, my goodness’ moment. I knew nothing about my grandmother working in a mill.”

Lavator Arnette (known as just Vator) was born in Dillon County on either May 24, 1890, or May 24, 1891, depending on which records one goes by. So she was either 18 or 19 when Hine photographed her. According to the caption, she had also been working in the mill eight years, which does seem likely.

She married William Fredrick (known as Fred) Burney on April 16, 1910. In the 1920 census, they were listed as living in Bennettsville, South Carolina, with three children: Evelyn, Clyde and John. Both parents could read and write. Fred was an auto mechanic. In the 1930 census, they were still living in Bennettsville, and Fred was still an auto mechanic. They had four children living in the home: Clyde, John, William and Mabel. In 1940, they were living in Laurinburg, North Carolina. Mr. Burney was still an auto mechanic. Oldest child Evelyn, who was with them in 1920, was living with them again. Lavator stated that she had left school after the seventh grade.

Lavator Arnette Burney died in Wadesboro, North Carolina, on July 30, 1976, at the age of either 85 or 86. She was survived by three children, four grandchildren, eight great-grandchildren, and one great-great-grandchild. Her husband Fred had died in 1969. Her descendants were not able to provide any pictures of her.

Edited interview with Lynn Abee (LA), granddaughter of LaVator Arnette. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on September 7, 2013.

JM: What year were you born?

LA: 1951. My mother’s name was Mabel, one of my grandmother’s children.

JM: What did you think of the photo of your grandmother and her sister?

LA: It was an “oh, my goodness” moment. I knew nothing about my grandmother working in a mill, and I don’t know anything about her sister Nettie, my great-aunt. I’d never even heard of her.

JM: Lewis Hine wrote that your grandmother had already been working in the mill for eight years, which means that she would have started when she was only 10 or 11 years old, because she was 18 or 19 in the photo. Where was she living when you knew her?

LA: Laurinburg, North Carolina. I’ve always lived in Columbia, South Carolina, about three hours from Laurinburg. We used go there at Christmas, and at other times as well, usually for just a weekend. I was the first granddaughter, so I always felt like I was pretty special to my grandparents. Her house was close to downtown. My brother and I would walk to the movies, or to the dime store to buy something. There wasn’t a lot to do there, so we did little things, like playing ball and hopscotch in the backyard. It was fun.

She liked cooking a big meal in the middle of the day, sometimes with the help of my grandfather’s sisters, if they were in town. They would put all the food out on the table, and after we ate, they would just put a table cloth over the food, and we would eat again that evening. When I got older, she was sick a lot. When the family sat and talked in the big dining room, she would lie in a bed that was in the room.

She made wonderful biscuits. When I was a child, she would give me a little bit of dough to play with. I used to sleep with my grandmother when I was a little girl. My grandparents had two double beds in the room, and my brother would sleep with my granddaddy in the other bed. When I saw the picture, I was amazed that I looked so much like her at that age.

*Story published in 2013.