Lewis Hine caption: Dillon Mill (tallest) Lizzie McKenzie, Has helped 1/2 year. Mamie Baxley (holding baby). Been in mill 3 years. Runs 4 sides = 40 cents a day. Maud & Daisy “help.” Location: Dillon, South Carolina, December 1908.

“She said she was on her feet 12 to 14 hours a day, and that she would stand on crates because she was too small to reach the machines. And when she went home, she still had chores to do.” -Patricia Graham, granddaughter of Lizzie McKenzie

The following appeared in the Galveston Daily News (Texas), on August 15, 1909 (less than a year after Lewis Hine took the photo above), under the headline: Child Labor in South Carolina Decreasing:

So far this year, 4,600 permits have been issued to children under 14 years of age to labor in the cotton mills of South Carolina. Many of these permits have been canceled, so that the number of children of that age actually at work is somewhat less. The figures given represent an estimated reduction of 1,500 since last year.

That showing will hardly be satisfactory to the foremost opponents of child labor: they will continue to gaze steadily at the 4,600, and give but a sidelong glance at the 1,500. But if that reduction indicates only a slow awakening to the evils of child labor, it nevertheless does indicate an awakening. It shows that the people of South Carolina are becoming aroused, and it gives promise of a time when public opinion will, if not abolish the system everywhere, at least reform it radically. For it is hardly conceivable that with the light that is breaking in the minds of men, they should much longer tolerate a system whose admitted evils are a thousand fold more than all the benefits that the sophistry of greed can claim for it.

People are beginning to see that even if an industry were dependent on the labor of children, the price it exacts is too much to pay for its success. They are beginning to see that it has consequences that are not justified even by the plea – in most cases an invalid plea – that the child’s earnings are indispensable to the family.

We are rightly alarmed by the increasing ravages of consumption, and yet we shall find in this system of child labor one of the most potent causes of the increased death rate from tuberculosis. Child labor in the mills is confinement at a period of life when exercise in the open air is indispensable to the making of a sound body. If disease itself is not actually contracted by the child, the man is made trebly pervious to it. He has been made to forfeit a large part of his chance of health and long life. If there were no other consideration, that of hygiene alone ought to move society to make war on the child labor system as it exists now.

But of course there are other and impelling reasons why we should do away with it. Weakened in body and denied all but the merest chance to get an education, what hope has the man to escape the thrall of the circumstances which tempted his parents to make a laborer out of the boy? It is said that the obstacles develop the latent strength of the boy. But while the handicap may be the making of one here, it will in the same time turn out 999 derelicts. The titanic man comes too high when he costs a thousand peasants who have sapped even of their ambition.

The factory child labor system is a system of bondage, as much in its essentials as was the institution of slavery – bondage, not of one man to another, but of man to an inexorable condition, in the making of which he had no part. Being that, at least a radical reform of it is as certain as it is that the world grows in benevolence and civilization, and of that fact no student of history can entertain a doubt.

**************************

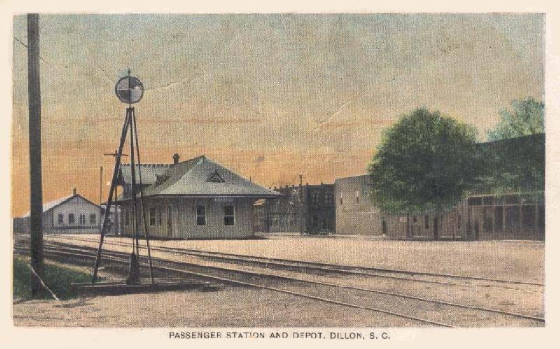

Lizzie McKenzie and the Baxley children lived in Manning Township, a section of the Town of Dillon, a small community that was dominated by the Dillon Mill and the Maple Mill. In the 1910 census, almost every family living in this section of town had at least several persons that worked at one of those cotton mills. Although Dillon had about 5,000 residents at the time, it was relatively isolated. The closest city of significant size was Charlotte, North Carolina, about 130 miles away. The railroad ran through town, stopping frequently at the busy station, and was the only practical means of public transportation. The original train station still exists and is a stop on the Amtrak line.

Despite the fact that many of these children would have worked as many as 10-12 hours a day, six days a week, it would be a mistake to assume that they had no life outside of the mills. Many of them would have had loving and caring parents, other relatives nearby, playmates (when they had time to play), church activities, and at least limited schooling. The mill families lived close to one another in the mill village, shared common experiences, and sometimes intermarried. In fact, Lizzie’s sister Mollie married Henry Baxley, one of the Baxley children not photographed by Hine.

In effect, they were more than just child laborers; they were people who had lives to lead, however difficult, and deserved to be treated with dignity. Lewis Hine believed that, and his respectful photographs of Lizzie and the Baxley children are good examples of that belief. He took 22 pictures in Dillon. Many of the child workers were apparently under legal age to work, or had started working in the mills at a very early age. He did not take any pictures inside the mills, probably because the owners refused to let him in.

Story of Lizzie McKenzie (followed by story of the Baxley children)

Lizzie was born Elizabeth McKenzie, but was known as Lizzie. Her parents were James and Minerva (Herring) McKenzie. According to the 1900 census, they were married in 1878. They had at least eight children, but only five were living in 1900. Lizzie was the youngest, but her date of birth is not certain.

South Carolina did not keep official birth records until 1915. Her year of birth in census records, on her marriage record, and on her death record conflict substantially. She may not have ever known exactly when she was born, which would have been common in rural states at that time. For this story, I will accept her date of birth as July 6, 1896, which appears on her death certificate. If that is correct, she would have been 12 years old when she was photographed.

Lizzie’s father died on August 31, 1904, according to the inscription on his gravestone at the Pleasant Grove Baptist Cemetery in Dillon. Lizzie was only eight years old then. According to the 1920 census, Lizzie, then 24 years old, was still working in a cotton mill in Dillon, as a spinner. She married Nathan G. Graves on December 12, 1924. He was apparently about 17 years older than she. Nathan, a widower, had two children from his first wife.

Sometime in the 1920s, Nathan and Lizzie moved to McColl, South Carolina, 25 miles south of Dillon. By 1930, they owned their home in McColl, where Lizzie and Nathan worked as spinners in a cotton mill. They already had three children of their own, and would later have three more. Lizzie’s mother died in 1931. In 1940, both still worked as spinners, but they now rented a house in the town of Hamer, fives mile north of Dillon. They later moved back to McColl, where they stayed the rest of their lives.

Nathan died in 1963. Lizzie died 15 years later, on October 14, 1978. She was apparently 82 years old.

When I began my research, I found her marriage record and death record, and then her obituary, which is posted on FindAGrave.com. I finally located her granddaughter, Patricia Graham.

Edited interview with Patricia Graham (PG), granddaughter of Lizzie McKenzie. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on August 6, 2013.

JM: When were you born?

PG: I was born July 8, 1951, in Bennettsville, South Carolina.

JM: Did you live near Lizzie?

PG: Yes, pretty much all my life, until she died.

JM: What the first place you remember her living?

PG: 108 Walters Street, in McColl, where she lived all her life after she moved from Dillon. I lived with her from the time my mom divorced, when I was three, till when I graduated from high school and got married.

JM: How many children did she have?

PG: Her husband, Grandpa Graves, had two children from his first wife, and then she died, and he married my Grandmama Lizzie. They had six children: my mom Ann and her twin Nan, who died young (at 11 months), and Jack, Alfred, Lucille, and James.

JM: What kind of grandmother was she?

PG: She was a good, wholesome, kind and compassionate grandmother. She was awesome.

JM: What are some of the things you did together?

PG: I would help her can vegetables and plant her garden. I would help shell the beans and the peas. We would pick huckleberries and blueberries, and we would bake. She taught me how to make biscuits.

JM: Do you make stuff now that your grandmother used to make?

PG: Yes.

JM: Do you have her recipes?

PG: Well, she would have to tell me how to make things, because she didn’t get to go to school for very long, so she couldn’t read. But she could write her name and she could count money. It made her sad a lot of times that she couldn’t read. She would always be saying to me, ‘Get your education. No one can take that away from you.’ I loved to read when I was growing up. The bookmobile would come around, especially in the summertime, and I would get books and read stories to her. When my aunt was living in Germany, Grandmama Lizzie would get letters from her, and someone would have to read them to her. She paid her bills with money orders. She didn’t have a bank account. When we went to town sometimes, she would get money orders and I would have to fill them out.

She babysat for my brother and me, and sometimes for my cousins, and she would sing old hymns. We had an iron post bed, one of those real old-timey beds, and she would get us all in that bed and sing songs to us. She would sing ballads and true stories that happened to people. That’s one of my favorite memories of her. I wish we had been able to record that.

She always loved coffee. When I was little, she started me drinking coffee. She would pour it in a saucer for me so it would cool, and I then would sip it from the saucer. And now my seven-year-old grandson wants me to give him coffee, so I sometimes give him a little bit when his mom says it’s okay.

She always told me her name was Elizabeth Betsy Ann McKenzie, and I would laugh and tell her that she had a lot of names for one person. She would tell stories about her life growing up. Her father died when she was young. That’s why she had to quit school and go to work in the cotton mill. She said she was around 10 or 11 when that happened. She said she was on her feet 12 to 14 hours a day, and that she would stand on crates because she was too small to reach the machines. And when she went home, she still had chores to do.

She also worked in the mill when she moved to McColl, after marrying my Grandpa Graves. One day, some machinery fell on her feet and crushed one of them. After that, she always had poor circulation and problems with her feet and legs. She could not take any action against the mill because all of her children were working there pretty much then, and she did not want them to get fired.

When I was a little girl, and somebody in the neighborhood would get sick, or somebody was out of work, or somebody had a baby, or somebody died, Grandmama Lizzie and I would take a wagon she had and go from door to door and collect what we called ‘food poundings.’ And then we would give the food to the person in need.

She was a very simple person. She never really had a lot of material things. She just appreciated her family. That is what made her happy. Everybody came to her house on Sunday. It was like the central meeting place for the family. But when she died, there was nobody else to keep that going. We had big porches in the South, and the neighbors would come over on Saturday nights and talk, while we kids would play. We would put cloth in pots and set them on fire to chase away the mosquitoes.

She told us that she went to Myrtle Beach when she was very young, but there wasn’t much there at that time. When she was old and in poor health – she had kidney problems – she said, ‘Before I die, I want to see it one more time. So we went in August of 1978, a month before she died, and we stayed about five days. She enjoyed herself very much. She was in a wheelchair by that time, but her mind was still sharp as a tack. She wore her hair long, and it was still dark.

JM: Did you go to college?

PG: Yes. I went three years at Francis Marion University, in Florence, South Carolina. But then my mom got cancer, so I had to put everything on hold and I couldn’t finish. I worked for the Post Office for about 15 years. For the past 13 years, I‘ve been working as a patient advocate for a community health center. Both of my girls went to college.

JM: What did you think when you saw the picture of your grandmother?

PG: I had mixed emotions. I was sad, and it made me cry. But then I realized that Mr. Hine was trying to do something good. He saw that child labor was bad. It breaks my heart to know that she never really had a childhood. If you worked in a mill from sunup to sunset, what kind of childhood could you have? Her life was hard. She didn’t have a lot to look forward to. We had a big family reunion a couple of weeks ago, and I made copies of that picture for everyone.

Grandmama Lizzie was my buddy. I’m a lot like her. I’m very short, but my mother was very tall, and so are my brothers. Sometimes people call me ‘Little Lizzie.'”

“Grandmama Lizzie’s birthday was July 6. When she was buried, my mama got mixed up and put my birthday on the gravestone. I told her to leave it, and that Granny would not mind having my birthday on her stone.” -Patricia Graham

*Lizzie McKenzie and Baxley children story (below) published in 2013.

Story of the Baxley Children

Lewis Hine caption: Dillon Mill (tallest) Lizzie McKenzie, Has helped 1/2 year. Mamie Baxley (holding baby). Been in mill 3 years. Runs 4 sides = 40 cents a day. Maud & Daisy “help.” Location: Dillon, South Carolina, December 1908, Lewis Hine.

Lewis Hine caption: Dillon (S.C.) Mills. Charley Baxley. Has doffed 4 years. Gets 50 cents. Had been out hunting. Dillon, South Carolina, December 1908.

The Baxley children were born to John and Etta (Hayes) Baxley, who were married about 1890, and had a total of at least seven children. The children’s dates of birth cannot be reliably established because all of them were born before South Carolina officially recorded births, and the information in the census is not consistent from decade to decade. Nor can we be sure that the dates of birth given on their death records or gravestones are reliable.

Although the children showed up in the census, death records and obituaries, it was very difficult to locate descendants that had useful information. In fact, I found only one surviving child of the six Baxley children, the 91-year-old daughter of Charlie Baxley. I interviewed her. She was delighted to see her father’s photograph. She was charming and easy to talk to. Surprisingly, she is still working (four days a week) as a bookkeeper and accountant for her church. But she didn’t give me any significant personal recollections of either her father, or his brothers and sisters. So this story is based on a few facts she told me about each of the Baxley children, and what I found in official records and newspaper archives.

John and Etta Baxley and their children lived in Dillon as early as 1900. John died of a ruptured appendix in November 1906, which means that the children lost their father just over two years before Hine photographed them. In 1910, the entire family except the two youngest children, Hattie and Inez, worked in the cotton mill. Only Charlie and his mother could read and write. Their given ages were as follows: Henry (19), Charlie (16), Minnie (14), Maude (11), Daisy (11), Hattie (8), and Inez (3). Henry did not appear in the Hine photos.

In 1920, Etta Baxley and daughter Inez lived together in Dillon, in a mill house next door to Lizzie McKenzie, the other girl in the Hine photograph. Etta was still living in Dillon in 1930, with Hattie and Inez. Etta died a year later.

The Baxley children. All photos of the children taken by Lewis Hine, in Dillon, South Carolina, in December 1908.

Charlie Covington Baxley married Mamie Lee Thompson on May 13, 1913. They had six children. He worked in the textile mills until he retired at the age of 65. He had very little schooling, but could read and write. Charlie died on November 7, 1961, at the given age of 68. Mamie died in 1972. Both died in McColl, South Carolina. I could not find a picture of his gravestone.

Minnie Baxley married Alton Fowler. They had three children. She worked as a spinner while her children were growing up, and until she retired. Alton also worked in the mill. She died in McColl on September 3, 1964, at the given age of 69, a year after Alton died.

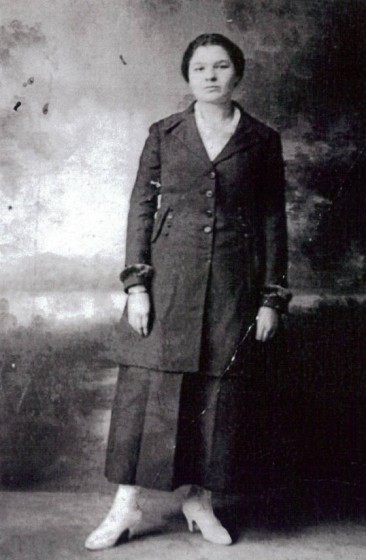

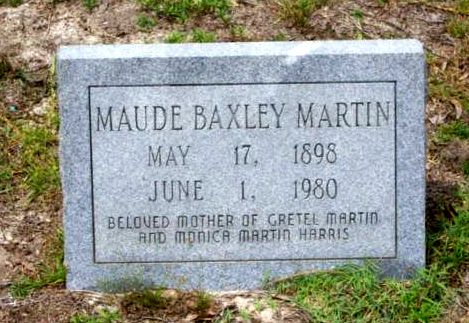

Maude Baxley married Solon Martin. They had five children, but one died as an infant. She was a spinner in the mills until she retired at age 65. Solon died in 1956. Maude died in McColl on June 1, 1980, at the given age of 82.

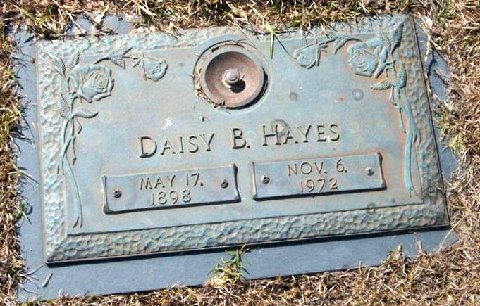

Daisy Baxley was the twin sister of Maude. She married Andrew Hayes. They had one child, a daughter. She was a spinner in a cotton mill until she retired at the age of 65. Andrew died in 1941. Daisy died in Dillon on November 6, 1972, at the age of 74.

Hattie Baxley married twice, first to a Mr. Bayley (first name undetermined). They had one child, a daughter, born in 1939. I do not know if the marriage ended in divorce, or whether he died. Her second marriage was to Samuel Harison. They had no children. Hattie worked most of her life in the cotton mills. Samuel, also a cotton mill worker, died in 1955. Hattie died in McColl, on July 2, 1961, at the given age of 59. She is buried at Rogers Cemetery in McColl, but I could not find a picture of her gravestone.

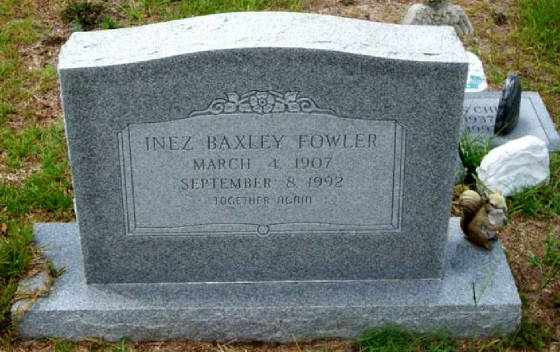

Inez Baxley married John Dalton Fowler. Known as Dalton, he was a textile worker. He was the brother of Minnie’s husband Alton. They had one child, a daughter. Inez worked in the mills as a spinner until she retired. Dalton died in 1958. Inez died in McColl on September 8, 1992, at the given age of 85.

All six of the Baxley children shown in the Lewis Hine photographs worked virtually their whole lives in the textile mills. All were born and raised in Dillon. Daisy remained in Dillon, but the other five children lived most of the rest of their lives in McColl, only 25 miles from their hometown.