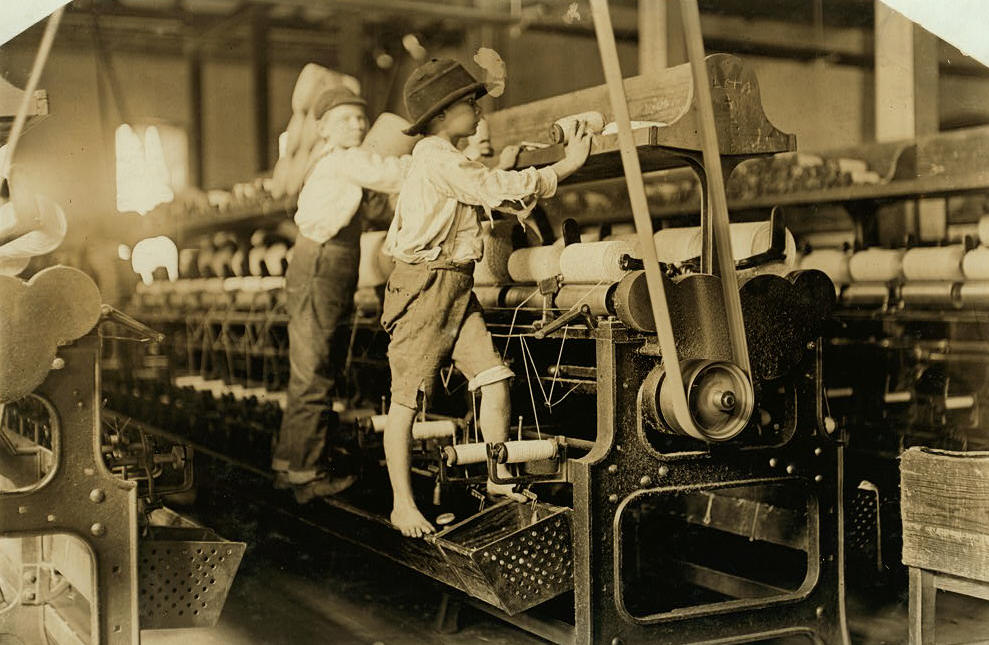

Lewis Hine caption: Boys working in Bibb Cotton Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga. Smallest boy–Otto Sheldo–2 yrs. in mill. Next, Jack Bowman–4 yrs. in mill. Next, Clement Olford–5 years in mill gets .75 a day. Next, Lawnie Williams–8 years in mill, gets .65 a day. Next, Henny Potter–2 yrs in mill. Two boys on left hand end are country boys just beginning to work, get 50 cents a day Witness, S.R. Hine. Location: Macon, Georgia, January 19, 1909.

Lewis Hine caption: Doffer boys in Bibb Mill #1, Macon, Ga. Location: Macon, Georgia, January 1909.

Lewis Hine caption: Group at the Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon Ga. This is one of the mills of the Bibb Mfg. Co., See label on photo 538 for profits made. Jan. 19, 1909. Location: Macon, Georgia.

Hundreds of orphans have been helped by the President of the Industrial and Orphan’s Home at Macon, Ga., who writes: “We have used Electric Bitters in this institution for nine years. It has proven a most excellent medicine for stomach, liver and kidney troubles. We regard it as one of the best family medicines on earth.” It invigorates the vital organs, purifies the blood, aids digestion, and creates appetite. To strengthen and build up thin, pale, weak children or run-down people, it has no equal. Best for female complaint. Only 50c at R.E. Green’s. -Advertisement (made to look like an article) published in several newspapers on January 19, 1909, two days after Lewis Hine photographed Otto

Lewis Hine took 32 photographs in Macon in January of 1909. The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, and the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938 eventually took bogus medicines such as “Electric Bitters” off the shelves. The Keating-Owen Child Labor Act of 1916, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 eventually eliminated most child labor in the United States.

Otto Shelton grew up, served in World War I, married, raised a family, and worked most of his life as a railroad mechanic. Only one building, now vacant, remains at the site of the former Bibb Mill in Macon. Its big sister, the Bibb Mill in Columbus, Georgia, once one of the largest cotton mills in the South, burned to the ground in 2008. In two more generations, almost no one will remember either of those mills, and in one more generation, there may be no one living who personally knew Otto.

In 1906, three years before Otto was photographed, Georgia enacted its first significant child labor law. It prohibited the employment in any factory or manufacturing establishment of children under the age of 10 under any circumstances. Starting in 1907, the law began prohibiting children under 12, except when a sworn certificate from the county ordinary stated that the child in question under 12 was an orphan with no other means of support, or had a widowed mother or disabled father dependent on its earnings. After January 1, 1908, night work between 7pm and 6am was prohibited to all children under 14 in factories, and all such children under 14 had to be able to read and write and have had at least 12 weeks of schooling.

According to most records, Otto Harrison Shelton was born in Macon on April 28, 1898, so he would have been 10 years old when he was photographed by Lewis Hine, who said in his caption that Otto had been working two years in the mill already. He was not an orphan, nor did he have a widowed mother or disabled father dependent on his income, so he was clearly working illegally. Investigations at the time by the National Child Labor Committee indicated that it was not unusual for cotton mills to employ children as young as eight or nine, especially in Georgia and South Carolina.

The census clearly showed that the “Otto Sheldo,” as misspelled in the caption, was Otto Shelton. I found his death record quickly and then obtained his obituary from the Macon Public Library. One of his survivors was his daughter, Polly Amerson, and I located her right away.

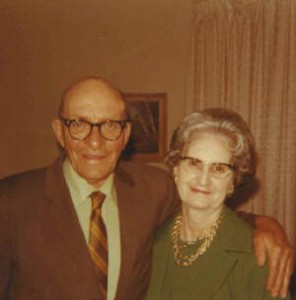

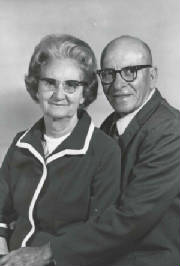

Otto was the oldest of at least seven children born to Oliver and Lavenia (Mitchelli), who married about 1896. Otto married Agnes Lee Lowe in 1920. They had five children. Otto worked for the fire department, and later as a house painter, and then for the Central of Georgia Railroad. He passed away in Macon on February 2, 1976, at the age of 77. Agnes passed away in 1993, at the age of 89.

I interviewed daughter Polly, and her daughter Denise, who provided some photos of Otto.

Edited interview with Polly Amerson, daughter of Otto Shelton; and Denise Goings, granddaughter of Otto Shelton (and daughter of Polly). Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 27, 2013.

JM: What do you think of the picture?

Denise: Had it not been for your call, we would never have known about it.

Polly: I can’t express how I felt when I saw it. It’s just miraculous. Of course, it’s a disgrace that those children had to work in the mills. But I think it made him a very strong person.

JM: Polly, what year were you born, and where were your parents living at that time?

Polly: I was born in 1932. They were living in East Macon, but I don’t remember what street we were living on then.

JM: How many children did your parents have?

Polly: Five. I had four older brothers.

JM: What did your father do for a living when you were growing up?

Polly: Before I was born, I think he sold vegetables out of his car. Then he worked for the fire department in Macon. When I was growing up, he was a painting contractor. He painted houses and stuff like that. Much later, he worked for the railroad. He was a fireman and a conductor.

JM: Did your mother work outside of the home?

Polly: No.

JM: When did they get married?

Denise: They got married on December 24, 1920. It’s right here in the family bible.

Polly: They met at a fair.

JM: Did you know that your father worked at the Bibb cotton mill when he was a boy?

Polly: Yes, I did. He told us he worked in the mill as a child, because his mother and father told him to. He said that it was really hard, and that he was so little, that he had to stand on a platform to change the spindles.

Lewis Hine caption: 1-19-1909. Bibb Mill No. 1. Many youngsters here. Some boys were so small they had to climb up on the spinning frame to mend the broken threads and put back the empty bobbins. Location: Macon, Georgia.

JM: When was your mother born?

Polly: She was born in 1904. When she was young, she had to work in the mill because her mother died and her father was in a wheelchair because he was injured in the war (World War I).

JM: How far did your father get in school?

Polly: I don’t know, but he could read and write.

JM: What was he like as a father?

Polly: He was just wonderful. I was the baby of the family and…

Denise: She was the only girl. Does that answer your question?

Polly: He was always there for us, anything we needed, any place we wanted to go. We had a station wagon. When I was a small child, every Sunday afternoon, we would go and get ice cream. I went hunting with him and fishing with him. He taught me how to shoot a rifle and all kinds of other things. He was just a great dad.

JM: So he taught you some of the things that boys did then.

Polly: He sure did. I think it made me a stronger woman.

JM: What was your mother like?

Polly: She was always at home. She cooked three meals a day, and she took care of all of us. One time, I guess it was in the early 1940s, during the war, Daddy was working as a train conductor. My mother decided that she wanted to work. So she got a job working at a plant that made ammunition. We called it the Fuse Plant. She worked one day. When my father came home, he said to her, ‘You will not be going to work anymore.’ So she never went back.

JM: Did your father serve during World War I?

Polly: Yes, but just for a short while.

JM: When did he retire?

Polly: He worked until he had a heart attack.

Denise: I was born in 1957. My grandfather passed away when I was about 19. I was the apple of his eye.

JM: What did you and your grandfather do together?

Denise: He taught me how to shoot a BB gun. We used to spend time together just talking. Anywhere I wanted to go, he would take me. When I was 16, I had the car taken away from me because I went somewhere I shouldn’t go. Then my grandfather called me and wanted me to take him somewhere. I told him I couldn’t go because Mom wouldn’t let me drive the car. He said, ‘You get in that car and come over, and I’ll take you and buy you your own car.’ But he didn’t when my mother found out about it. He played games with me. He taught me to play poker. I took piano lessons, and he loved it when I played for him. He would make requests. He loved the ‘Marines’ Hymn,’ and I would play it over and over again. He was just a fun guy to be around. He was always laughing and telling jokes.

JM: How tall was he?

Denise: He was about six feet tall. All his sons were six feet tall.

Polly: He used to tell us that he never had shoes as a boy. And in the picture, he was the only one who wasn’t wearing shoes. And it was in January.

Denise: But he had a hat on, Mom. Why didn’t his parents take the money they paid for the hat and buy him shoes instead?

Polly: My father always wore a hat.

Denise: My grandfather was always giving me money. My mom told me that when I was a little girl, he gave me a five dollar bill. I looked at it and said, ‘I don’t want this. I want one with two numbers.’ I remember one time when we were riding on the Interstate. They planted a lot of clover alongside the road. My cousin was driving, and I was in the back seat. My grandfather was sitting in the front passenger seat. I said, ‘Oh, that clover is so pretty. I wish I had some.’ My grandfather told my cousin to drive closer to the edge of the road, and then my grandfather opened the car door and reached down a grabbed a bunch of clover and gave it to me.

JM: Polly, how far did you get in school?

Polly: I graduated, and so did two of my brothers. I worked for a short while at Woolworth’s, and then I got married and had Denise.

JM: Denise, did you go to college?

Denise: Yes. I got my nursing degree and an undergraduate degree in health care administration from Macon State, and then I got a master’s from American Sentinel University. I work as a nurse now.

JM: Is the Bibb Mill still there?

Denise: There is only one building left, and it is right across the street from the hospital I work at. How ironic is that?

Otto Harrison Shelton: 1898 – 1976

*Story published in 2013.