Lewis Hine caption: A menace to Society. The Padgett family. The entire family including the mother totally illiterate. No one could read or write. The mother does mill work some. Alice, 17 years has steady job. Makes from $5 to $6 a week. Alfred, 13 years now, worked here when he was 12, and in other mills before that. Makes $4 a week. Recently crippled by getting his hand caught in the cogs of a spinning machine. Richard just reached 11. Been working here 1 year; began when he was 10. Makes $2.40 a week. “The work runs him down too.” William, 6 years old, nearly blind. Lizzie, 5 years old. Home in utter neglect; filthy and bare. When investigator called the mother had been gone about an hour, leaving a roomer’s 3 months old baby in the cradle before an open fire on the hearth, and only two children 5 and 6 years old – one nearly blind, playing around. She came back and fed them a lot of cheap candy. What will Society reap from its neglect of this family? Shaw Cotton Mills. Location: South Weldon, North Carolina, November 1914.

“My father was always blind in one eye, and he couldn’t read, but he could still do a lot of things. What always amazed me was that he could do math problems in his head. I admired him. He didn’t go to school, but he busted my britches if I didn’t go to school.” -Bob Padgett, son of William Padgett

My first reaction to this photograph was a familiar one for me. It was sadness at the family’s seemingly desperate situation, coupled with the hope that I could track them down and discover that they somehow found a way out. But my second reaction was very different. Mr. Hine’s caption seemed uncharacteristically harsh. He seemed to be calling the family, “A menace to society.” And he seemed to be partially blaming the mother for the situation: “Home in utter neglect; filthy and bare”…”When investigator called the mother had been gone about an hour, leaving a roomer’s 3 months old baby in the cradle before an open fire on the hearth, and only two children 5 and 6 years old – one nearly blind, playing around”…”came back and fed them a lot of cheap candy.”

I was concerned that if I managed to contact descendants, how would they react to the caption? I certainly wouldn’t be happy to find out that my family had been referred to as a menace, nor would I be pleased that someone I didn’t know had told me about it.

I read the caption over carefully numerous times, and slowly came to the tentative conclusion that Hine was referring to the neglect of the family as a “menace,” not the family. His final comment in the caption is, “What will Society reap from its neglect of this family?” But I was still bothered a little by his comments about the mother. But then it occurred to me that 11 years before Hine took the picture, he had studied sociology at the Columbia University School of Social Work. At that time, social work was beginning to focus considerably on child care and public health issues, so it would have been understandable for Hine to make these observations.

I contacted a historian and teacher whose work I admire, Dr. Kate Sampsell-Willmann, author of Lewis Hine as Social Critic. I asked her what she thought about it, and she replied:

“I do not believe Lewis Hine was calling the Padgett family a menace. My impression is that someone else added the title, “A menace to Society,” at another time. If you remove that title, the rest of the caption sympathizes with the family as being neglected by society, not as a danger to it, which is much more in keeping with the tone Hine used in his own captions. As a social scientist, Hine had learned to investigate and copy down information rather than jump to conclusions while in the field. Abstract or angry titles would have been added after reflection; they did not accompany notes on conditions.”

“Although I have yet to discover the original caption, several anomalies lead me to believe that the caption was added later. First, and most important, is the incongruity between such condemnatory language and the innocence on the face of at least the youngest child. Not once did Hine blame a child for the conditions spread by child labor, no matter how he felt about the adults in the picture. To indict the entire family would be fundamentally out of character. If he wrote that title (which I very much doubt), the menace to society was not the family but the conditions they lived in. Furthermore, in the photograph Hine made of the injured Padgett child, the caption is congruent with Hine’s overall body of work.” (see photo below).

“If anything, Hine blamed the mother’s parenting skills: leaving a baby alone, giving the children nothing but candy, children not learning to read or write. Hine’s son Corydon was born in December 1912, so he would have been nearing his second birthday when this picture was made. Hine may have subconsciously compared his wife Sarah as a mother, with the Padgett mother. Either way, if read in its totality, with some doubt as to the first title, it is clear that Hine’s concern was for the condition the children lived in, not for how they might injure the rest of us.”

I concurred, and continued with my research, knowing that I would have to explain our collective assessment to whatever family members I located.

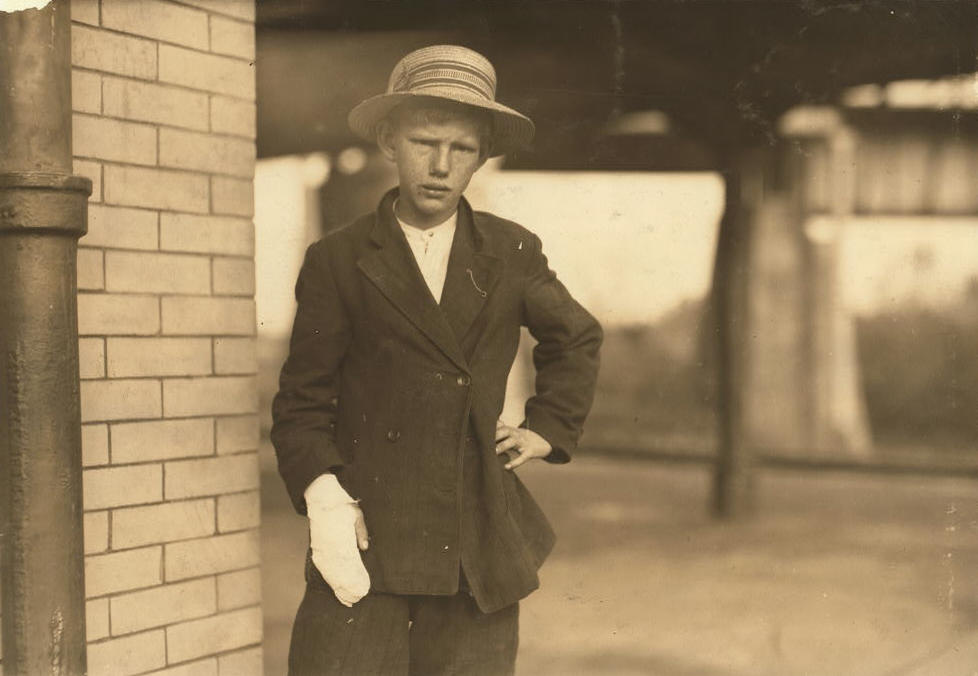

Lewis Hine caption: Shaw Cotton Mills. An accident case. Alfred Padgett a doffer says he is 13 years old now, but worked when he was 12, and in other mills for 2 years before that. “I got my hand caught in the cogs of the spinning machine last week, and lost part of my finger. It stopped the machine, and I tell you it hurt. It pains me a lot now. Don’t you think they orter pat me wages while I’m out with this bad hand? No, I can’t read or write, but I think my mammy knows how to spell my name.” Not a member of the family could read or write. Location: Weldon, North Carolina, November 1914.

“On Saturday nights, my grandfather would give each of us kids a nickel, and stand in the yard and tell us when it was safe to cross the street. And then all of us would get an ice cream cone and stand there until he would tell us it was okay to cross the street again.” -Dianne Hilliard, granddaughter of John Alfred Padgett

Lewis Hine caption: Shaw Cotton Mills. Overseer grouped all the workers, and several of them are surely under 13, and several began work under 13 last year. Location: Weldon, North Carolina, November 1914.

“Weldon, N.C. The mill buildings for the Shaw Cotton Mills, in the course of construction, are expected to be ready for the machinery early in the summer. It is estimated that the buildings will cost about $24,000. The equipment will consist of 5,129 spindles for manufacturing 2/24’s to 2/30’s yarns.” –Posselt’s Textile Journal, April 1908

“At Weldon there are two very progressive cotton mills, the Shaw Cotton Mills Company, and the Weldon Cotton Manufacturing Company. The Shaw Cotton Mills have in operation 10,000 spindles, and the Weldon Manufacturing Company has 3,636 spindles. The former manufactures hosiery splicing yarn on cones, while the latter manufactures men’s cotton knit underwear. The raw materials used in these mills are bought from the cotton growers in the county, and these two cotton mills, in conjunction with those situated at other towns in the county, furnish a local market for cotton.” -Halifax County: economic and social: a laboratory study in the Rural Social Science Department of the University of North Carolina (1920)

Lewis Hine caption: Group of workers in the Shaw Cotton Mills going home. Several violations. Location: Weldon, North Carolina, November 1914.

According to NCpedia, an online encyclopedia managed by the Government and Heritage Library at the State Library of North Carolina, the 1909 North Carolina child labor laws set the minimum age limit for factory work at 13 years, with no more than 66 hours of work allowed per week. In 1913, a state law was passed making school attendance compulsory at least four months of each year for all children between the ages of eight and 12. In his caption for the photo of the whole Padgett family (at top), Hine indicated that two of the boys were working illegally, and one had worked illegally the previous year.

After establishing that Alfred Padgett was commonly known by his first name of John, I located his obituary, as well as the obituary for his son, Joseph. One of the survivors listed was Dianne Hilliard, niece of Joseph and granddaughter of John. I called Mrs. Hilliard, and then emailed her the photos. She replied: “I am stunned, absolutely stunned. I had no idea that my grandfather and his family ever lived and suffered as witnessed by Mr. Hine.” She accepted my explanation regarding the “menace to society” comment in the caption.

At her suggestion, I called Bob Padgett, son of William Padgett, one of the boys in the photo of the family. He was equally stunned by the pictures, and he told me that he was currently working on compiling information about his family. He was not pleased with the “menace to society” comment, but he also accepted my explanation. However, he added, “Somebody needs to officially delete that from the caption.” He led me to the names and phone numbers of other descendants. Unfortunately, several of them passed away before I could interview them, and several more had extended illnesses that substantially delayed completion of my research for the story. All told, it took almost two years to finish my research. Many family photos were provided by Dianne Hilliard; Bob Padgett; and Carrol Padgett, widow of Bob’s brother Jerry.

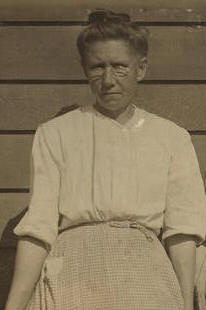

Annie Padgett, the mother, was born Annie Hardison, about 1874, in Williamston, Martin County, North Carolina. She married James Robert Padgett in 1888, when she was about 14 years old, and he was about 17. According to the 1900 census, they were living in Williamston, with two children, 6-year-old Mary and 2-year-old Alice (the oldest child in the Hine photo). James was a fisherman. In 1910, the family was still in Williamston, but Annie was a widow, with three more children, John, Richard and William. Mary, the oldest child, was not listed, but she may have died, because Annie told the census taker that she had given birth to seven children, and only four had survived. Annie worked as a “wash woman.”

At the time of the census, April 23, 1910, Annie was apparently pregnant, because I learned later that Lizzie, the youngest girl in the Hine photo, was born on October 10, 1911. Her full name was Mary Ann Elizabeth, but she was known as Elizabeth. That would mean that Annie’s late husband, in order to have fathered Elizabeth, would have died between January and April of 1910. Both Annie and daughter Alice were listed in the census as illiterate, but the literacy of the other children was not indicated (Hine said in his caption that all of them were illiterate). According to Hine’s captions in 1914, it appears that the family had been living in South Weldon since about 1912. Actually, South Weldon was not a town, but simply a census district in Weldon.

After further research, and interviews with Dianne Hilliard and Bob Padgett, I was able to compile considerably more information on the lives of Annie, and all of the Padgett children in the photographs. I will start with Annie; then Alice, Elizabeth and Richard, whose direct descendants I was unable to interview; and then William and John, whose direct descendants I did interview.

Annie Padgett

In the 1920 census, we learn that Annie had remarried, to William Hayes, year not specified. He worked for a lumber company. They lived in Weldon, with Annie’s children: Alice, John, Richard and Elizabeth; Annie’s widowed mother; and William’s 15-year-old son James, probably from a previous marriage. All the children, except Elizabeth, were spinners in a cotton mill. In 1930, Annie, now a widow for the second time, lived in Weldon with daughter Alice. Annie passed away in Weldon in 1931, at the age of 57. At her request, she was buried in her hometown of Williamston.

Alice Padgett

Alice Padgett was born in Williamston, on August 12, 1893, according to her death certificate. But Hine gave her age as 17, which would mean she was born in 1897. Census records while she was living with her mother indicate she was born in 1897. So I will settle on 1897. According to North Carolina death records, Alice gave birth to an unnamed boy on August 19, 1917, but the baby died about seven weeks later, of malnutrition. She was unmarried, and the father was listed as unknown. In 1930, Alice (last name Gilliam) was living with mother Annie, in Weldon. She was married, but Mr. Gilliam was not listed in the home. Alice was a winder at a cotton mill. In 1932, Annie Elizabeth Gilliam was born in Weldon to Alice and William Gilliam. Alice and William divorced sometime in the next five years, because in 1938, a second child, Charles Alsberry Norton, was born, and the father was her second husband, Clemon Monroe Norton. Alice gave birth to Charles when she was 41 years old. Mr. Norton, who was 13 years older than Alice, had been married once before, and had five children. His first wife died. Mr. Norton died in Weldon in 1948.

Alice passed away a year later, of a cerebral hemorrhage, on January 4, 1949. She was 51 years old. According to her obituary, she died: “a short time after she was admitted following a sudden attack on the street in Weldon. Mrs. Norton was between Elias’s store and Shaw’s Mill on First Street when she was apparently seized with a stroke and fell to the sidewalk. Aid was summoned immediately, but there was no doctor immediately available and she was rushed by automobile to Roanoke Rapids Hospital. She died a short time later. Surviving are one daughter, Elizabeth, and one son, Charles.” Her sister, Elizabeth Hanna, was listed as a survivor, and lived in Newton, Illinois. That helped me locate her later.

I found her son Charles, and sent him the Hine photos of his mother and family, but he did not respond. Subsequent attempts to contact him failed. Her daughter Annie passed away in 2013. I could not identify any other living direct descendents.

Elizabeth Padgett

Mary Ann Elizabeth Padgett was born October 19, 1910, in Williamston. Several documents list her year of birth as 1911, but evidence clearly indicates it was 1910. So she was three years old in the Hine photo, not five as stated in the caption. She was the only child in the family that was not working in the mill at the time. In 1920, she was living with her mother, in Weldon; but in 1930, she was married to Charles Ray Hanna, and lived in Wheeler, Jasper County, Illinois. They had married that year, and both were living with Charles’s parents. In 1932, a daughter, Doris, was born.

According to the 1940 census, Elizabeth was a lodger in a house in Newton, also in Jasper County, Illinois, and worked as a maid in a hotel. She stated that she had graduated from high school, though there is no other evidence to support that. She was divorced. Her daughter was not listed as living with her, but instead was living in Newton at a different address with what appeared to be unrelated adults. I did not find out why, or even if it was correct. Former husband Charles was still living with his parents in Wheeler. Bob Padgett, William Padgett’s son (and Elizabeth’s nephew) told me: “My Dad told me that Elizabeth was mad at the family. My cousin told me that she moved to Illinois. He said they went there one time and she didn’t want to have anything to do with them.”

I found her death date in the Social Security Death Index, and then her obituary and a photo of her gravestone. She died in Olney, Illinois, on December 22, 1983, at the age 73. Her obituary named daughter Doris, her only child, as a survivor, also of Olney. I called her and told her about the picture of her mother. She had just gotten out of the hospital several days earlier, but she was interested, and we talked for about 20 minutes. She told me that her mother did not remarry and lived part of her life in Chicago. She was surprised and delighted about the Hine photograph of her mother, but she told me that her mother often said that she didn’t want to stay connected with her family back in North Carolina. I mailed the photograph to Doris, but she took ill again and passed away in the hospital before I could talk to her again.

I found her obituary, and after waiting for a few weeks, I called one of her daughters and told her about my conversation with her mother, and about the photo of Elizabeth, her grandmother. She was interested, and she characterized both her mother and grandmother as “great women.” But after sending her the photo, I could not get in touch with her. Later, several Padgett descendants sent me a photo of Elizabeth with her brother John, both children at the time. So I emailed the photo to Elizabeth’s granddaughter, but she did not reply. So I have to assume that she is no longer interested.

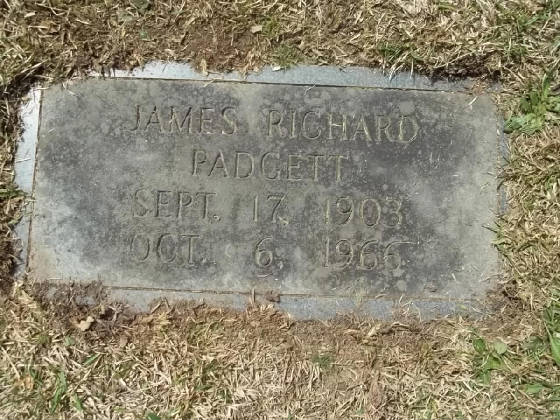

Richard Padgett

James Richard Padgett, known as Richard, was born in Williamston on September 17, 1903. In 1920, he was living with his mother in Weldon, and worked as a spinner in a cotton mill. He married Pearl Pearson in 1925. Their first and only child, Hazel, was born in 1926. In 1930, they were living in Weldon, next door to his mother, and his brother John. His brother William was living with him. Both Richard and Pearl worked in a cotton mill. In 1940, they were living in Weldon. Richard was working in Patterson Mills in Roanoke Rapids. He stated in the census that he had left school after the second grade. Pearl passed away in 1960, at the age of 57. Richard passed away in Roanoke Rapids on October 6, 1966, at the age of 63. Due to health problems, daughter Hazel was unavailable for an interview, and I could not locate any grandchildren. Richard’s nephew, Bob Padgett, told me: “Uncle Richard was a lead man in the spinning room, and he fixed things, like the gears. He was a heck of a nice guy. When I was young, I worked in the mill with him, and he looked out for me.”

William Padgett

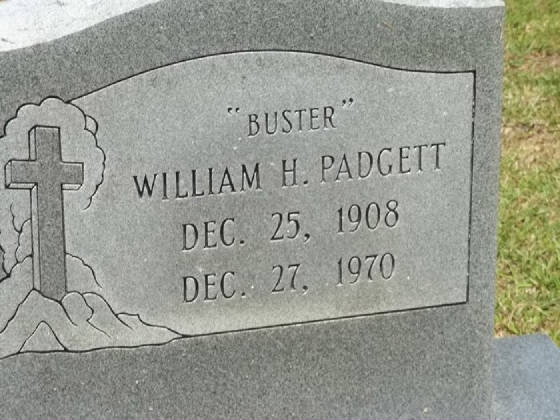

William Henry “Buster” Padgett was born on December 24, 1908, in Williamston. He was the boy that Hine described as “nearly blind.” He was five years old in the Hine photo, not six as stated in the caption. I could not find him in the 1920 census, but I found him in the two succeeding censuses. In 1930, he was living in Weldon with his brother Richard, and was not employed. In 1940, he was living in Weldon with wife Dora and his son Bob, just three months old. William was working for the federal program known as the WPA. They had one additional child, Jerry, in 1945. William died in Roanoke Rapids on December 27, 1970, at the age of 62. I interviewed his son, Bob.

Excerpts from interview with Bob Padgett, son of William Padgett. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on February 23, 2013.

I was born in 1939. My mother’s name was Dora. My parents married in about 1938, when my father was about 30, and my mother was about 16. My brother Jerry was born in 1945. He died in 2006. We were the only two children. My parents finally divorced, and my mother married again and had two children by her second husband. My father worked in the cotton mills. He worked for J.P. Stevens. He also did plumbing work and electrical jobs, wiring houses and churches, which he did while he was still working his regular job at the mill. I used to help him wire houses. I would be the guy who went through the attic, because I was small.

When I was born, we were renting a house right behind a textile mill in South Weldon. It was kind of a bungalow, with three bedrooms and an outhouse. It was out on Route 301, near Oak Ridge Cemetery. My mother also worked in the textile mills, at the River Mill.

My father was always blind in one eye, and he couldn’t read, but he could still do a lot of things. What always amazed me was that he could do math problems in his head. He could tell you about a lot of things. With no education at all, he had a lot of foresight. My dad would sometimes tell me, ‘One day, they’re going to have cars that go around on electronic tracks.’

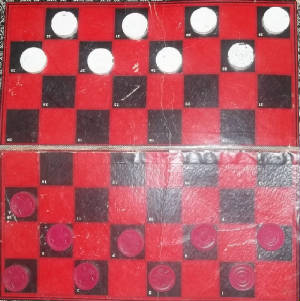

His nickname was Buster. He was a wiz at checkers. They had a lot of little backyard stores around where we lived, and they would have checker tournaments. He had a problem seeing the black checkers when they were on the black squares, so he painted the black checkers white. I still have those checkers.

He was a wonderful guy, and I admired him. He didn’t go to school, but he busted my britches if I didn’t go to school. I graduated from high school and took some courses at a number of colleges, but I didn’t get my degree. I worked in ship building in Newport News, Virginia.

My father used to sign his name with an “x.” When I learned how to write, I taught him how to sign his name, and he thought that was marvelous. He no longer had to make an “x” on his checks.

William Padgett’s other son, Jerry, who passed away in 2006, compiled some of his memories of growing up in Weldon. His son, Jerry Padgett Jr., posted them on a website, with the title, “My Dad’s Autobiography.” Carrol Padgett, widow of Jerry Sr., gave me permission to include excerpts in this story.

I was born on August 15, 1945, in the old hospital in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina. At this time my mom and dad lived in a house in South Weldon, across the street from a Shell gas station on Route 301. I don’t remember living there but was told this by my dad. The first house that I remember living in was an old company house we rented on what was called “Cotton Mill Hill.” The houses had been built by the Audrey Spinning Mills for its workers, but the mill had been out of business since the Depression. The old building, its fire water tank, and the mill pond were still there, though the building was a warehouse for storing cotton bales.

We lived, to start with, on the hill east of the old mill overlooking Oak Ridge Cemetery, the black cemetery. Daddy worked at Patterson Mill in Roanoke Rapids, where Uncle John and Aunt Rosa worked also. Uncle John was Dad’s brother. Dad never had a car, so he rode to work with John and Rosa, who lived a few blocks away down on Washington Avenue across from Ham’s Cafe. Mom had a job at the River Mill in Roanoke Rapids. As best I could tell, times were good then. Grandma kept my brother Bobby and me, and cooked meals and cleaned the house for Mom and Dad.

Once in the winter I saw Grandma pour hot water on the back door steps to melt the ice, so the steps wouldn’t be so slick. Then one evening, Bobby choked on a piece of ice in his tea. Everybody was upset that he was choking, so I told Grandma to pour some hot water down him. After the crisis, everybody thought the hot water idea was funny.

I remember Mom playing in the yard with us kids. She would laugh and run with us playing kick the can. All of the houses I ever lived in when I was young had a swing on the front porch. Dad loved to swing, so at night after the games, supper and bath, my next event was to join Dad on the swing. I would climb up on the swing and put my head in Dad’s lap where I would go to sleep and magically awake the next morning in my bed. If the weather was a little cool in the evenings, Dad would tell me to go and get his old coat. He would tell me to go and get the booga bear coat. I spent many nights with my head in Dad’s lap with my booga bear coat pulled up tight, listening to him tell stories about when he was little and about when he worked at the power plant that made electricity from the water flowing through the canal on the river downtown.

He told me all the stories like The Three Pigs, Goldilocks and all the rest. We never lived far from the railroad tracks of the Atlantic Coast Line, so the old stories on occasion would be about ghost trains and people who got killed on the tracks. One he told was about a ghost train back when he was young. People would walk down the side of the tracks to town and see the light from an oncoming train. They could see the light and the train and feel the wind as the train went by, but there was no sound. It was absolutely quiet.

Daddy was a hard worker and very, very smart. He was digging a hole in our backyard one day to make a drain system for the kitchen sink he had put in. The hole had field lines and all, just like a modern septic tank system. Now you might not think it such a big deal now, but back then the only water was a spigot out in the back yard. Nobody around our neighborhood had indoor water or a bathroom. The bathroom was an outhouse. So having an indoor sink and running water was a very big deal.

Dad was always looking for ways to make life a little easier for Mom and Grandma. It was while Dad was digging on one of the field lines that I walked up behind him and he hit me on the head with a pick. Now Dad didn’t know I was behind him, so it was an accident. This brought on my first experience with doctors and hospitals.

Daddy had a shop in the back yard where he would fix radios and electrical appliances. There were not many then, but he loved fixing them. He put up a big light bulb on a tall post and it lit up the whole yard. It was the only light in the neighborhood. I have always thought what a shame it was that he never went to school. Dad could do math in his head as fast as anyone I knew, but couldn’t read or write. One side of Dad was bright and futuristic, but on the other side he was also superstitious about black cats and walking under ladders. He knew all about the phases of the moon. He used it to plant his garden every year. We would always have a big garden that produced more than anyone else’s.

Once I had been playing way down in the woods. They called it Marsh Island. I had become lost, and after walking a long way, it turned dark. Boy, was I scared. After walking a while longer I saw the flicker of a light. At first I thought it was a star low on the horizon. Then I realized it was a street light, but only barely visible. I started walking in that direction trying all the time to keep my eye on the light. Now when you are walking down a path in the dark, that’s hard enough, but when you leave the path in order to try and walk straight toward a target, the light, that’s a whole new ball game.

Still scared, tired, lost, and wet from crossing all the streams and ditches, I finally arrived at the light by a cinder block building on the back side of a gravel pit way down in the woods. It was where the local rich men went to play poker. There were a lot of thrown away playing cards which were strange to me. I had never seen anything like them before, but they were pretty. I managed to find my way out to the highway and back home. I must have been about seven or eight at the most, but somehow I remember it very clearly, maybe for what happened later.

I arrived home to a worried dad and grandma, but I did not get scolded or spanked or anything. They were relieved just to know I was okay. After a few weeks when everything had gotten back to normal, I began to think about that lost cinder block building with the cards outside and what the place might look like in the daylight. So off I rambled, and I soon found the place, which was just a block building, light pole and trees. I picked up some of the cards, just the ones with pictures, like Jacks, Queens, and Kings, and proudly started off for home. It was something new to play with. I had them laid out on our small back porch when Dad came up and saw them. At first I thought he had seen a snake. That’s when I noticed he was looking at the cards and then at me. So that’s the story about how I found out that Daddy didn’t allow cards at all.

The first time I saw a funeral was of a black man that had been killed in the Korean War. The black cemetery was nearby, so my playmate and me went over to see what all the commotion was about. So there we were, two little white boys in a crowd of black people all dressed in suits and their finest dresses. The women were crying and so were some of the men. There we were in bib overalls. One in the group told us about how the man had been killed in the war.

I thought it was some sort of church service. There were praying, singing, and preaching. All of it was familiar to me, having grown up in a church, but I didn’t know that was done at a cemetery. Suddenly an Army bus pulled up and soldiers with guns started getting off the bus. My friend and I, who were already scared, just froze at the sight of grown men with guns getting off a bus in a cemetery. Some of the soldiers were white and some were black.

Quickly the soldiers fell into line, smartly shouldered their weapons, and marched over beside the flag- draped coffin where the officer in command of the squad told how the man had died in battle honorably defending the country. Then the soldiers fired their guns, giving the twenty-one-gun salute. I noticed the spent shell casings falling to the ground, and I wondered if they were to be picked up by the soldiers. Finally my friend and I went back home.

I asked Grandma what was going on. She told me about a war in some faraway place across the ocean, namely Korea, and how the man who had died had given his life to defend our country. That is why the soldiers had come to give him a military funeral. The next day I went back to find that no one had picked up the shell casings. I had never seen any before, so I picked up all that I could find and kept them to play with.

My life growing up, from my earliest recollections, was very close to the Weldon Pentecostal Holiness Church. My dad was a deacon. Grandma was a Sunday school teacher, and my step-granddad, Blackie Harlow, was a substitute preacher. We went to church every Sunday, Sunday night, and to a Wednesday night prayer meeting. One of my earliest memories was sitting in a church pew and realizing my feet only reached the edge of the pew. This was in what they called the old church.

The old church sat on the corner facing Elm Street. Just beyond Elm Street are the main line tracks of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. I remember sitting in the back row of pews looking out the church window when the trains came by. There was so much noise the preacher would stop preaching until it had passed. I thought the trains were very pretty. The steam was huffing and the smoke trailed behind over the cars. As quick as they had come, they rolled away and the services would continue. There was always singing in our church, but no choir until a few years later. Everyone sang together, and this was something I enjoyed a lot.

I started school in September of 1951. The first building I was in was the brand new elementary school. My first grade teacher was Ida May Cheatham. My brother Bobby would ride me to school on his bicycle. All the roads to school were dirt and gravel, which meant a lot of little holes and a very rough ride. At first I rode on the crossbar, but then Dad decided I could ride better if Bobby’s bike had a basket. Well, the bicycle bounced so bad that I was afraid of bouncing out. So Dad bought a luggage rack for Bobby’s bike and that was just right. I would ride to school and home sitting on the back hugging my big brother. I did that for three years.

Every Friday, Bobby, who is six years older than me, went to classes in another building with the big kids. My building was for classes first and second only. Friday was payday for Dad, so Bobby would ride downtown with me to wait for Dad. School let out at three and Dad got off at three, but he and my Uncle John and my Aunt Rosa would stop in Roanoke Rapids to get their checks cashed. Roanoke Rapids is four miles away from Weldon. So it worked out that there was always a little time to wait before they got to town. Bobby and me would always wait at the same place, which was the sidewalk beside the A&P store facing Main Street on the corner. Up the street behind the A&P was the library, so I would sometimes get a book to read while waiting, keep it all week, and exchange it the next Friday. This began my love affair with reading.

Well I’m sure by now you are wondering why we were waiting for Dad. Each week, Dad would give Bobby and me an allowance of 50 cents. I know that may not seem like a lot of money, but in 1951, a Coke was 5 cents, a gallon of gas was 18 cents, a gallon of kerosene was 10 cents, and a ticket to the movies at the Center Theater was 14 cents. It included a double-feature, a cartoon and a serial. At the theater, candy bars were 5 cents, bubble gum was 2 for 1 cent, and popcorn was 10 cents a box.

A year later in the second grade I got sick with pneumonia. Back in Grandma and Dad’s day a lot of people died from this. So they were very upset and worried and took very special care of me. But with a few shots of penicillin, I was up and running in a few days. They insisted that I stay in bed. Dad kept the heater on day and night. We heated our house with a coal heater. Dad would get the stove pipe red hot. Grandma had me under four quilts, and I listened to the radio and read.

John Alfred Padgett

John Alfred Padgett was called Alfred by Lewis Hine, but he was known as John. He was born in Williamston on April 20, 1901. In his caption of the photo at left, Hine said:

“Alfred Padgett a doffer says he is 13 years old now, but worked when he was 12, and in other mills for 2 years before that. “I got my hand caught in the cogs of the spinning machine last week, and lost part of my finger. It stopped the machine, and I tell you it hurt. It pains me a lot now. Don’t you think they ‘orter pat me wages’ while I’m out with this bad hand? No, I can’t read or write, but I think my mammy knows how to spell my name.”

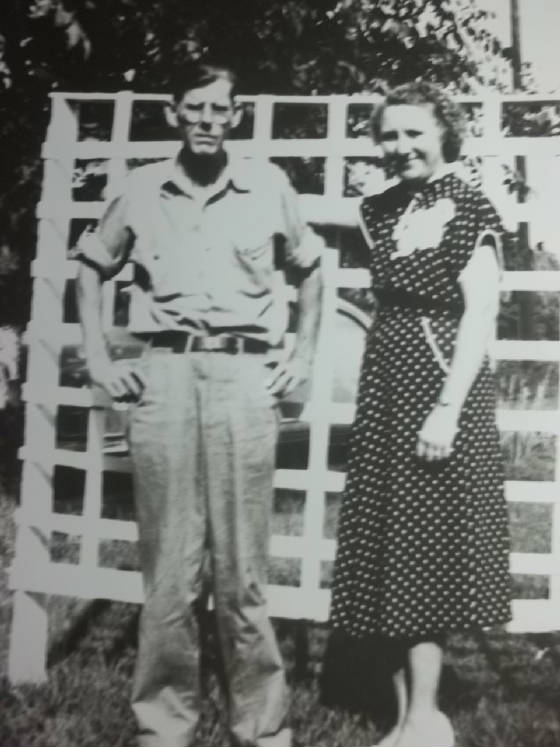

But John, as did the other Padgett children, overcame considerable adversity and went on to lead a productive and meaningful life. Photos of him later in life indicate no evidence of the injury he described to Hine in the caption (“lost part of my finger”), nor did the descendants I spoke to remember noticing a finger injury. It may have been a serious cut that healed.

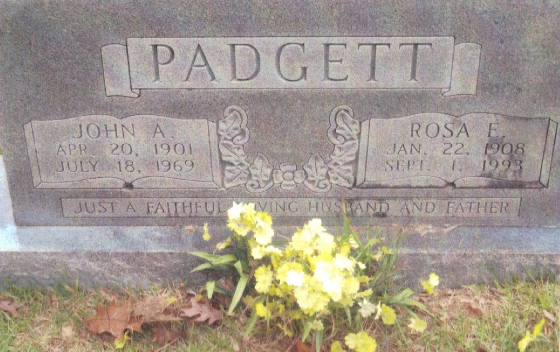

In 1920, he was living with his mother and siblings, in Weldon, where he worked as a spinner in a cotton mill. He married Rosa Carter in about 1923, and in 1930, they were living in Weldon, where John continued to work as a spinner at Patterson Mills in Roanoke Rapids. They had three children, John, William and Margaret. A son, Walter Grady Padgett, was born in 1934, but he lived only six months. In 1940, they continued to live in Weldon, and now had two more children, Jesse and Joseph. Both John and Rosa were still working at Patterson Mills.

John Alfred Padgett passed away on July 18, 1969, at the age of 68. Rosa remarried, and died in 1993, at the age of 85. All of their children were accomplished adults. Their son, Joseph Stancil “Shorty” Padgett, is a notable example.

The following is from Joseph Padgett’s obituary: “He received his undergraduate degree from East Carolina University, his Master’s degree from The College of William and Mary, and his advanced degree in education administration from the University of Virginia. He then went on to become a teacher and principal in the Hampton City Schools for approximately six years. From there he became the assistant superintendent in the Fluvanna, Prince William and Loudoun County Schools, where he was directly responsible for overseeing a construction budget of more than 80 million dollars annually. Upon his retirement from the Loudoun County Schools, he served as director of Policy Services for the Virginia School Boards Association for two years.”

Edited interview with Dianne Hilliard (DH), granddaughter of John Alfred Padgett. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 13, 2013. Also included are several written comments from Dianne.

JM: What was your grandfather like?

DH: He and my grandmother doted on their children and grandchildren. By doting I mean – I can’t say that nothing was denied, because they didn’t have unlimited financial resources – but they gave as much as they could give. Forgive me if I become emotional. They had six children, including my mother, but one died in infancy. My mother, Margaret, had two older brothers and two younger brothers. She had a very special relationship with her father. They were very close. I would really get tickled at him because he would call her ‘Mah-get,’ in a slow drawl. We spent a lot of time with my grandparents. Sometimes we would go down for dinner on a Saturday night, and sometimes we would visit after church on Sundays.

There was a drive-up hamburger stand right across the street from their house. It was a teenage hangout. On Saturday nights, my grandfather would give each of us kids a nickel, and stand in the yard and tell us when it was safe to cross the street. And then all of us would get an ice cream cone and stand there until he would tell us it was okay to cross the street again. He did that for as long as I can remember. If I had gone down there when I was 18 years old, he still would have said, ‘Do you want an ice cream cone?’

My grandparents were employed for many years at the Patterson plant of J. P. Stevens Company, the location of which was one block from our high school in Roanoke Rapids. Many times during inclement weather, my brother and I would walk into the school yard after dismissal to find our grandparents patiently waiting. No matter how many friends were with us, nor the distance they lived from school, they were graciously welcomed by my grandfather into the warm, spacious back seat. When there were too many to fit comfortably there, the girls sat in front, and I was given the honor of sitting in my grandmother’s lap. After ensuring each of our friends was safely through their front doors, he drove my brother and me home and began the fifteen-minute drive to Weldon. Before he and my grandmother finally were able to settle into their own home for the evening, one final stop was necessary: making sure my grandfather’s younger brother, William, who commuted with them daily, was securely home.

They took us to the coast on the Outer Banks every summer. The mills would close the week of July 4, so that is when my grandparents would take a vacation, and they liked to have their children and grandchildren with them. I remember a cottage that they rented for several years. It was owned by a family in Roanoke Rapids. I thought it was wonderful. My dad did construction, and when the weather was good, he worked, so my mother took us.

I have a picture of my grandfather and me. According to the note made by my mother on the back of the photograph, she took it in the summer of 1947 when I was about a year old. When I saw the photo as an older child, I remember my mother telling me that I was interested in the box of matches my grandfather kept in his shirt pocket so he let me hold it for a few minutes. I imagine I must have thought it was the most wonderful thing. When he tried to take it from me, I began to cry. From the look on his face, it is apparent he regretted having to do that. Although I probably did not give it up easily, I’m sure he was able to distract me with something equally fascinating.

My grandfather was kind and generous, and so was my grandmother. She loved us all – again, forgive me if I get emotional – she loved her children and grandchildren unconditionally. She loved to cook and serve big family-style meals. She lived a long time after my grandfather died. She was sick most of 1993, and I remember that summer I went down there and helped take care of her. She told me one day, ‘All I want to do is to cook a big meal and have all my family here.’ I told her that I understood how she felt, but that she was just too ill to do that. I said to her, ‘Let’s reminisce about the times that you did it.’ So we talked about the food she would prepare and all the other things, and it seemed to ease her mind somewhat.

JM: When I first looked at the Lewis Hine photograph of the family, I didn’t know anything about them except the caption, and I had to wonder if those children had any chance in life at all. But based on what I have found, most of them turned to be, if not greatly successful, successful enough, and are remembered fondly by their children and grandchildren. That’s quite an accomplishment.

DH: You’re absolutely right. I’m 66, and looking back on it now, they gave a lot to their children, a lot that they themselves did not have growing up. I think they were determined that life would be better for their children, just as I want my children’s lives to be better than mine. It’s wonderful that they could pull together and make their lives better. I’m sure it wasn’t easy.

JM: And I’m sure it wasn’t easy for Mrs. Padgett, the mother of the children in the photograph. Lewis Hine made some critical comments about her skills as a mother, but we really don’t know the difficulties she would have had to face. Her first husband had died only three years before she was photographed. Hine may not have known that. At least, he didn’t mention it.

DH: As my mother always said, ‘You shouldn’t judge somebody until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes.’ We don’t know what she had to bear. Had I been in her situation, with all those children, and losing my husband, and not having an education, I don’t know what I would have done. I had the best grandparents anybody could ever have. All of their children were hardworking, productive, law-abiding citizens. They all had their faults, but they were good people, all of them. It could have turned out differently.

My grandparents began their marriage with nothing but each other; worked diligently to forge a better quality of life for themselves and their children; mourned the tragic loss of an infant son; faithfully endured good-byes as each of their four sons left home to serve in the military, the eldest of whom was engaged in battle in Germany and Austria during World War II; gave emotional support to each other and to members of their extended families, including my grandfather’s mother and his siblings; welcomed my grandmother’s mother into their home, supporting and caring for her until her death; and created a positive, happy environment for each grandchild, all while they easily could have reasoned that, since they had suffered hardships as they matured, it was only fitting their children and grandchildren be likewise subjected.

It has been emotional to look back, realize their hardships and appreciate even more the family into which I was born. John and Rosa Padgett were exceptional people, remarkable really, and I will always be grateful for having been privileged to call them grandparents.

Elizabeth Padgett: 1910 – 1983

Annie Padgett: 1874 – 1931

William Padgett: 1908 – 1970

Alice Padgett: 1897 – 1949

Richard Padgett: 1903 – 1966

John Albert Padgett: 1901 – 1969

*Story published in 2013.