Lewis Hine caption: Sadie Pfeifer, 48 inches high, has worked half a year. One of the many small children at work in Lancaster Cotton Mills. Nov. 30, 1908. Location: Lancaster, South Carolina.

The following are excerpts from The Survey, Volume 21, published in 1909.

As to conditions in South Carolina, Mr. Hine thus states his opinion: “In general, I found conditions here considerably below those of North Carolina, both as to the age and number of small children employed, though several of the mill towns in North Carolina approach the worst ones in South Carolina. In Chester, S.C, an overseer told me frankly that manufacturers all over the South evade the child labor law by letting children who are under age ‘help’ older brothers and sisters. The names of the younger ones do not appear on the company’s books and the pay goes to the older child who is above twelve years.”

In South Carolina, Mr. Hine found a mill settlement, the Wylie Mills at Chester, with no schoolhouses accessible to the children. He found a boy of twelve, fifty-two inches high, who is a weaver running six looms and making a dollar a day, a boy who has been at work two years. The children themselves overstate their ages, their parents have misstated their ages. Illiteracy seems to prevail here. Many boys and girls could not even spell their own names. The mill schoolhouse is a shed-like structure and very small.

The present report and photographs on Lancaster confirm the report on the same mill early in the year, by Rev. A. E. Seddon, who examined forty-five children at work and found thirty-four illiterate. One little girl of seven had been working in the mill for eighteen months; that is, she went to work at five and a half years, though as the child is an orphan, this is not a violation of the South Carolina law. Children may legally work at any age in June, July and August if they have attended school four months that year and can read and write.

**************************

Today, as I write this, it’s been almost 105 years since Sadie Phifer became one of the haunting faces of child labor. It would be hard for most Americans now to close their eyes and inhabit her dark world; but in China and other South Asian countries presently experiencing their own industrial revolution, there are millions of girls like Sadie, mostly out of sight and out of mind.

The first major assignment given to Lewis Hine by the National Child Labor Committee was to photograph child laborers in Ohio and Indiana, in August of 1908, and then to travel to West Virginia to take pictures of children working in coal mines. He was not pleased with what he saw, and many of his captions reflect that. In early November, he began a three-month tour of the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida, and was shocked to see many child workers in textile mills who were seven to ten years old, and some in seafood canneries who were as young as four and five.

In Lancaster, South Carolina, authorities at a large cotton mill gave Hine permission to photograph children working at the looms and spinning machines, resulting in some of the most compelling and beautiful pictures he would ever make. In the one of Sadie, the spinning machine looks huge next to her. Since most child cotton mill workers toiled 10 to 12 hours a day, six days a week, daylight was something Sadie observed mostly through the windows behind her, if she ever had time to stop and look.

In my research, I learned that Sadie did not attend school beyond the second grade, apparently leaving so she could work. Hine photographed the mill school, and the public school where non-mill children went.

Lewis Hine caption: This is where the mill children go to school. Lancaster, S.C. Enrollment 163– attendance, usually about 100. There are over 1,000 operatives in the mill. These are all that go to school from this mill settlement, which is geographically a part of Lancaster, but on account of the taxes has been kept just out of the corporate limits. Nov. 30/08. Location: Lancaster, South Carolina.

Lewis Hine caption: This is where the other children go to school. Public School: Lancaster, South Carolina, November 1908.

Lewis Hine caption: The Lancaster Cotton Mills S.C. One of the worst places I have found for child labor. Location: Lancaster, South Carolina, December 1908.

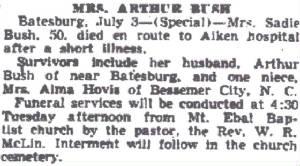

Sadie Phifer (called Sarah in the 1900 census), was born in Wadesboro, Anson County, North Carolina. Her death certificate states that her date of birth was March 31, 1900, but in the 1900 census, her parents gave her birth date as March 1899, a more credible date in my opinion, so I have settled on March 31, 1899. Her parents were North Carolina natives Caswell Thomas Phifer and Nancy Emerline (Childers) Phifer, who were married about 1884, when he was about 31, and she was about 19. Thomas had been married once before. They had at least eight children, only four of whom were living in 1900. Sadie was the youngest. At that time, the family was living in Lanesboro Township, Anson County, about 50 miles southeast of Charlotte. Mr. Phifer was a farm laborer.

By 1910, the Phifer family was living near the Lancaster Mills, in the mill village section called Gills Creek. Both Mr. Phifer and Sadie worked in the mill, he a picker, and she a spinner. She was not attending school. In about 1916, Sadie married Arthur Wallace Bush. He was about 23, and she was about 17. In 1917, Arthur enlisted in the Army. At that time, he and Sadie were living in Danville, Virginia. Arthur had been working at Dan River Mills, one of the largest textile mills in the South. Sadie probably worked there also.

After Arthur was discharged in 1919, he and Sadie moved to Rock Hill, South Carolina, where they both worked at the Rock Hill Cotton Factory. Sadie’s parents lived 25 miles away in Lancaster. According to city directories, Sadie and Arthur were living in Gastonia, North Carolina in 1927, in a mill village surrounding the giant Loray Mill, a textile mill that was to be the site of a historic and violent strike two years later. Her parents lived one block away. In 1928, Sadie’s mother died.

In 1930, Sadie and Arthur were living in Catawba Township, South Carolina, which includes part of Rock Hill and the Catawba Indian Reservation. Both were working in a cotton mill, probably the one in Rock Hill where they previously worked. Sadie’s widowed father and one of her sisters were living with them. Her father died in 1932, in Bessemer City, North Carolina, which is where Sadie and Arthur were living in 1940 (and as early as 1935, according to the census). They had one child, eight-year-old William Bush. Sadie and Arthur worked in an unidentified cotton mill. There were several in the city at that time.

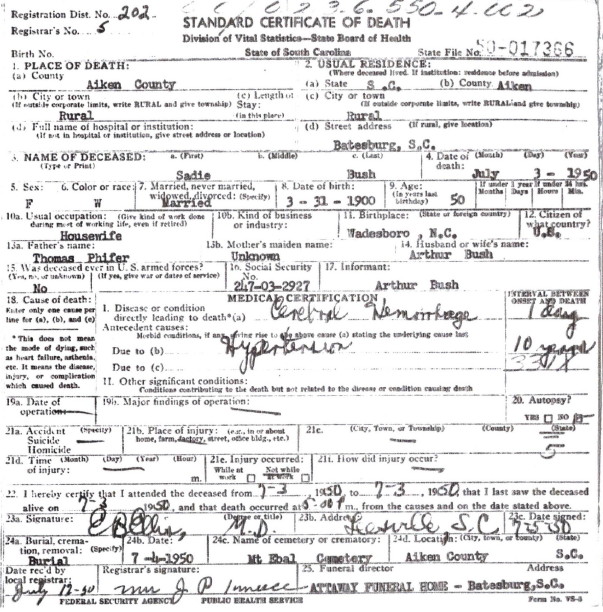

Sadie Phifer Bush died of a cerebral hemorrhage (stroke) on July 3, 1950, in Aiken County, South Carolina. She was only 51 years old. She was living with Arthur in nearby Batesburg (now called Batesburg-Leesville) in bordering Lexington County. She was buried in Mt. Ebal Cemetery in Aiken County. In her obituary, son William was not listed as a survivor, which leads me to believe that he died between 1940 and 1950. However, no one with that name and approximate year of birth is listed in the online death records for North or South Carolina. The only survivors listed were her husband and a niece. Arthur remarried, to Anne Pennigar, and then died in the Veterans Hospital in Columbia, South Carolina, on November 24, 1961. He had been living in Rock Hill. In his obituary, his only listed survivors were his wife and a brother. He was buried in Laurelwood Cemetery, in Rock Hill.

Unable to find any of Sadie’s descendants, or any living descendants of her siblings, I contacted the Aiken Standard, the leading newspaper in Aiken County, where Sadie died and was buried. A reporter agreed to write an article about my search for Sadie. It was published on March 31, 2013, along with the Lewis Hine photograph. No one responded.

So I made one more effort. I searched again for descendants of Sadie’s siblings, even though I had been down that road before using Ancestry.com and other genealogy sites. But this time, I tried Google. When I searched “Connie Phifer,” an older sister, I found a listing on FindAGrave.com. It was for an Alma Hovis, who died in South Carolina in 1975. Her mother was listed as Connie Phifer, married name Harris. I Googled her, and found the obituary of Connie’s son, Cole Harris, who died in 2001. He would have been Sadie’s nephew. The obituary listed a few survivors, one a daughter, Vicki Pilkey, who lived in North Carolina. I found her phone number, called her, and she confirmed that Sadie would have been her grand-aunt. I sent her the photograph and interviewed her. This is what she said.

Edited interview with Vicki Pilkey (VP), grand-niece of Sadie Phifer. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 12, 2013.

JM: What can you tell me about Sadie?

VP: When he was growing up, my daddy, who was Sadie’s nephew, lived with Sadie. She was like his older sister. I remember Daddy telling me tales, like him and Sadie fighting over who had to feed the mule. Neither one of them wanted to do it.

JM: In 1930, they were living in Catawba, South Carolina. Your father was 16 years old. He was living with Sadie and her husband Arthur. In 1927, Sadie and Arthur had been living in Gastonia. They worked at the Loray Mill.

VP: Daddy and his sister Aunt Alma worked there, too.

JM: In 1940, Sadie and Arthur were living in Bessemer City.

VP: They lived in what they used to call Newtown, which was a little mill village on the outskirts. My daddy talked a lot about Sadie’s husband, Arthur Bush. They traveled on trains and got work together when the Depression came.

JM: Did anyone ever tell you what Sadie was like?

VP: Well, I am very slow moving. Daddy always called me Sadie because she talked real slow and moved real slow, and I was just like her.

JM: She died of a stroke at the age of 50 or 51.

VP: She worked all her life in the cotton mills, and that will age you.

JM: Do you know anyone who might remember Sadie?

VP: Daddy and all of his brothers and sisters are gone. I don’t know of anybody else that would know anything about her.

Sadie Phifer: 1899 – 1950

*Story published in 2013.