“And she became the sad Carlotta. Alone in the great house…walking the streets alone…her clothes becoming old and patched and dirty. The mad Carlotta…stopping people in the streets to ask: ‘Where is my child? Have you seen my child?’ Poor thing. And then she died…by her own hand. -Edited from the screenplay for Vertigo

In Alfred Hitchcock’s classic movie, Vertigo (1958), retired detective Scottie Ferguson (played by Jimmy Stewart) is hired by an old friend, Gavin Elster, to follow his wife, Madeleine Elster (played by Kim Novak). Madeleine has been behaving strangely, and Gavin wants to know what’s wrong. At one point, Scottie observes Madeleine staring longingly at a portrait of Carlotta Valdes at an art museum.

Later she visits Carlotta’s tombstone. Scottie soon learns that Carlotta was mistress to a rich man by whom she had a child. When the man abandons her and takes the child, Carlotta is left to wander the streets, asking people “Where is my child?” She eventually commits suicide. When Scottie tells this to Gavin, he explains that Carlotta was Madeleine’s great-grandmother, and that the child was Madeleine’s grandmother. He is concerned that Carlotta’s ghost is beginning to possess Madeleine.

I have been haunted by Vertigo ever since I saw it more than 50 years ago. One of my daughters had the same reaction when she saw it many years later. When my wife and I made our first visit to Hope Cemetery in Barre, Vermont recently, she spotted Carlotta Miglierini’s tombstone. She cried out, “Look, it’s Carlotta!” It was a chilling moment. When we got over the shock, we wondered why it looked so much different than any of the other tombstones at the cemetery, and we felt sadness at its poor condition. Right away, I wanted to know who she was, and if there was anyone alive who remembered her.

Hope Cemetery was designed by Edward P. Adams, a famous landscape architect. It was established in 1895, on 53 acres of land. By then, many skilled artisans from around the world, especially Italy, had been immigrating to Barre to become a part of the booming granite industry. Silicosis, a respiratory disease caused by granite dust, was common among the artisans and sculptors who were breathing it in every day, and that led to an abnormally high death rate among them. Understanding that their lives might be shortened by their work environment, many of the workers designed their own tombstones to showcase their skills. It is estimated that 75% of the tombstones at Hope Cemetery were designed by the occupants of the graves. Now expanded to 65 acres and more than 10,000 tombstones, the site is a popular tourist destination.

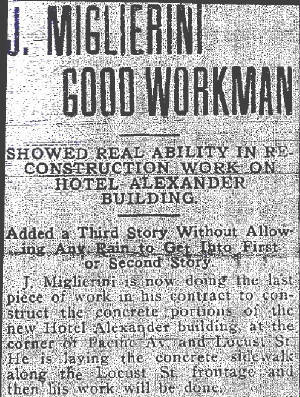

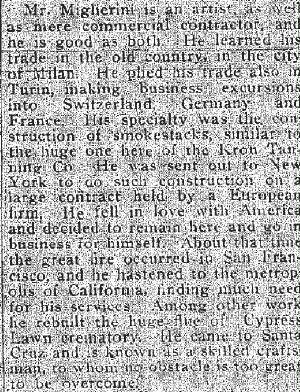

When we drove home, all I could think about was Carlotta. The next day, I logged on the Internet and started searching. At first, I found no records of her – not in the census, not in birth, marriage, death or immigration records, not even listed in the millions of family histories that amateur genealogists have posted on sites like Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org. But I did find a few people named Miglierini that were residents of Barre and Montpelier in the early 1900s, among them Aldo Miglierini. Very quickly, I found an interesting document posted online, titled Joint Resolution In Memory of Aldo E. Miglierini. Among other things, it said, “Whereas, Aldo E. Miglierini initially worked with his father as a tender, helping to construct the impressive brick tower that stands at the pinnacle of Hubbard Park; Whereas, decades later, in 1974, he continued his family’s contribution to Vermont’s premier building when he expertly reconstructed the wall behind the State House that his father originally built…”

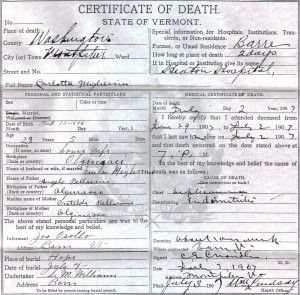

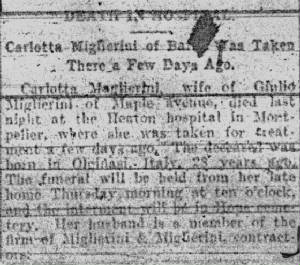

His daughter, Joan Kirby, was mentioned. I found her and gave her a call, thinking that she might know something about Carlotta. She was excited about my inquiry. She told me that she discovered Carlotta’s tombstone several years ago and wondered if she was a relative, but could not find much information. All she learned was that Carlotta married Giulio Miglierini, that her maiden name was Bellarini, and that she died of septicemia (a serious blood infection). She could not find anything more about Giulio, but she was hopeful my research might turn up something more. It did, but nothing to confirm that she is related to him.

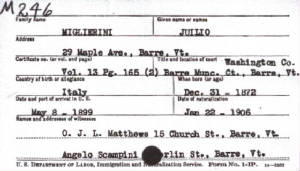

I tried searching a number of variations of Giulio and Miglierini on Ancestry.com, and was soon rewarded with the 1906 naturalization record (above) for Juilio Miglierini, of 29 Maple Ave, in Barre. It said he entered the US on May 8, 1899, and that he was born in Italy on December 31, 1872. Then I found a Julian Miglierini listed as a World War I draft registrant, living in Santa Cruz, California. He had the same date of birth. His occupation was brick layer. Then I found Giulio Miglierini, a cement contractor, in the 1920 census, still living in Santa Cruz.

He was living with wife Mary (later confirmed as Maria), and 15-year-old daughter Louise, born in Vermont. Wow, I thought, that means Louise was born before Carlotta died in 1907, so she must have been her daughter. She would be about 105 now, but I had visions of identifying her children, if she had any, and tracking them down. I imagined the prospect of talking to Carlotta’s grandchildren, and being able to send them my photo of the tombstone. Would they even know about her? It didn’t take long.

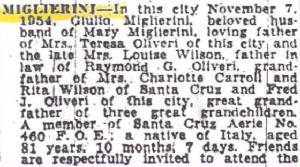

Next I came up with Giulio’s death record. He died in Sacramento on November 7, 1954, at the age of 81. I emailed the library in Sacramento and asked for a copy of the newspaper obituary. Meanwhile, I made another big discovery. Carlotta appeared to have had another child. In the 1910 census, “Julia” Miglierini is listed as a widower living in Santa Cruz, with his mother, Mary, and his two children, 6-year-old Louise and 10-year-old Teresa, born in Italy. And then Giulio’s obit popped up in an email from the library.

I was disappointed to learn that Louise had died before her father did. A few minutes later, I found Teresa’s California death record. She died in Sacramento in 1960. Her mother’s maiden name was listed as Bellarini, confirming that Carlotta was the mother. But I did have some people to track down: granddaughters Charlotte Carroll and Rita Wilson, and grandson Fred Olivieri. I found Charlotte immediately in the Internet White Pages and called her.

Of course, she was surprised by my inquiry. I asked her if Carlotta was her grandmother. She said, “I’ve always assumed that. I guess I was named after her. Charlotte is the English version of Carlotta.” She referred me to her sister Rita, whose daughter, Josephine Rifesi, was compiling the family’s history. I called Rita and wound up speaking to Josephine, who was amazed that I was doing research on her family. She told me that she and her mother had gone to Barre about 10 years ago.

“My mother knew that her mother, Louise, was born there, and she was interested in finding a birth certificate and other documents. We found the address of the house she lived in with Carlotta and Giulio, and we also found Carlotta’s death certificate. It said she was buried at Hope Cemetery. We went out there and drove through. Most of it was very pretty and well maintained. Finally, we found an older section, and I got out of the car and walked up a little incline, and then down a hill, and that’s when I saw Carlotta’s tombstone. I was stunned. My hands were kind of shaking. It was so unexpected. My mother thought it was wonderful, but it was in pretty bad shape. We took some pictures, but we had to fly back home that day, so we didn’t have any more time for research. When you do genealogy, every time you find out something, you have a dozen more questions. We still didn’t know what part of Italy Giulio and Carlotta came from. When we got home, we showed the pictures to my Aunt Charlotte, who was named after Carlotta.”

With Josephine’s help – she sent me copies of numerous documents and photos – and my own research, this is what I have learned:

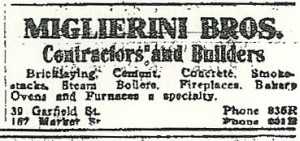

Giulio, Carlotta and Teresa came over from Italy in 1899, and settled in Barre. Louise was born in Barre on September 5, 1904. Carlotta died three years later. Given that Carlotta’s tombstone was made mostly of cement, the family assumes that it was constructed by Giulio and one or two of his brothers, who were cement contractors and also lived in Barre. Shortly after Carlotta died, Giulio, his two children, and his mother, Mary, moved to Santa Cruz, where one of Giulio’s brothers, Angelo, had recently moved. They became partners in Miglierini Bros, a construction company, which later rebuilt the Water Street Bridge in Santa Cruz. In 1909, Giulio married Felicita Piazzini. They had no children, and divorced in 1914. Shortly after, Giulio married Maria Paolinelli. They had no children, and were still married when he died in 1954.

Teresa died in Sacramento on June 1, 1960, at the age of 60. She had one child, Frederick. Louise died in Santa Cruz on October 4, 1941. She was only 37. She was married twice and had two children, Charlotte and Rita.

Carlotta Bellarini Miglierini was born on February 10, 1879, in Olginasio, a village in Besozza, just north of Milan in northern Italy. Her parents were Angelo and Crotelda Bellarini. She died on July 2, 1907, at the age of 28, after spending her last two days at Heaton Hospital, in Montpelier. Other than that, we know very little about her.

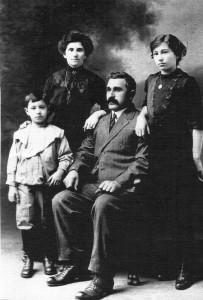

Like the haunted woman in Vertigo, was she the “sad Carlotta?” I’d like to imagine otherwise. Despite the struggles she had to endure, and her tragic death, she was probably thankful for her husband and her two children, and the opportunity to start a new life in Vermont. According to several sources, her native town is situated in the region of the lakes, with Lago Maggiore being only six kilometers away, and features breathtaking views of the Alps. In many ways, Barre would have reminded her of her homeland. I’d also like to imagine that in the afterlife, she saw her husband live a long time and attain a modest share of the American Dream. What did Carlotta look like? My research has turned up no photographs of her. So we must be content to see her image reflected in the faces of her children and grandchildren.

I asked the family if they were interested in restoring Carlotta’s tombstone, and they said they were, so I talked to an experienced granite sculpture in Barre. He kindly offered to inspect it. He told me that the cement is cracked in a number of places, causing the tombstone to be very fragile. His believes that it cannot be restored.

Two More Stories: Angelo Bernardina & James Walker

I was walking down a dirt road that loops around in the southern portion of Hope Cemetery, and I came to a huge monument that had eight columns and a carved likeness of some sort of angel or saint holding a cross. At the bottom was inscribed the name Calcagni. Suddenly I noticed what appeared to be a tiny tombstone about 50 feet away, on the edge of the woods. It was in a shady spot, making it barely visible.

I headed down and stared at it. Compared to what I had seen in the cemetery so far, it looked totally out of place, like a pup tent in a campground full of RVs. I muttered to myself: “Does anyone ever notice this? Does anybody know who James M. Walker was? What did he do to deserve this humble home in a neighborhood of mansions?” Then I turned around and saw Angelo staring right at me. A man of privilege, I thought. His family must have had lots of money to afford this. I took some pictures and decided to seek out more information when I got home.

Angelo Bernardina

The first thing I found when I searched Bernardina and Barre on Ancestry.com was the 1988 Vermont death record for Mrs. Edvige Dindo Slora, whose father was listed as Angelo Dalla Bernardina. Louis Dindo, a son, was listed as the informant. I found him immediately and called him up. I asked him about his grandfather’s impressive tombstone.

“My mother told me that a friend of his by the name of Pelligrini, that was living in Quincy (Massachusetts), cut the bust from a picture, and as he remembered him. The granite is what they call Westerly Red, which comes from the red granite quarries in Rhode Island. People from Barre went down to work in the stone sheds in Quincy, and some came up from Quincy to work in Barre.”

“The tombstone would have been expensive. The family was probably what you would call middle class. My grandfather was involved in the Barre Union Cooperative Store, on Granite Street. They sold food. My mother told me he was also involved with making and selling wine. After he died, my grandmother bought a duplex at the end of Railroad Street, so she must have had enough money to afford that. My mother got married a year or two after Angelo died. I was born in 1931. My father passed away eight months later. They had just bought a home. My mother took in day boarders. That’s how she survived, until she remarried in 1942.”

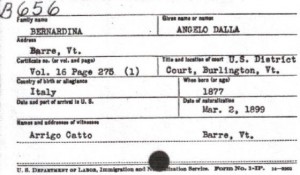

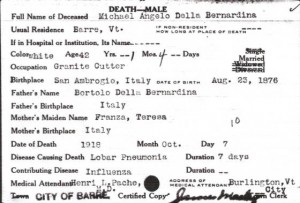

According to Mr. Dindo, and various official records, Michael Angelo Dalla Bernardina (he later dropped the Dalla), was born in San Ambrogio, Italy on August 23, 1876. His parents were Bortolo Dalla Bernardina and Teresa Franza. He entered the US about 1897, and was naturalized on March 2, 1899. He married Luigia Richelli in 1900. A granite cutter, he worked for the Harrison Granite Company, in Barre.

The Barre Union Cooperative Store, with which Angelo was involved, has great historical importance in the US. The following is from Cooperation in New England, Urban and Rural, by James Ford (1913):

“Immigrants from Italy have not founded cooperative stores in this country to a large extent, despite their practice in co-operation at home. The chief cause is probably the instability of population through frequent returns to Italy and migration within this country. But Italians in America are also largely urban, whereas co-operation succeeds most easily in the smaller centers where push-carts and bargain sales are infrequent. The Barre Union Co-operative Store of Barre, Vermont, founded by Italian stonecutters in 1901, was until 1908 the only incorporated Italian store in New England.”

“At the beginning of 1910 this association comprised a membership of 124 Italian stonecutters, earning a typical wage of $3.20 per day. They carried on a business for 1909 of $30,000 on a capital stock of only $1,200 and with a reserve of $2,600. With exceptional enterprise they began in 1911 to publish a fortnightly journal, La Cooperaiione, dedicated to propaganda for co-operation, thrift, improved housing, social hygiene, mutual benefit associations, peoples’ banks, and immigration. In addition to reviews of important social movements in Italy, this journal has devoted space to the consideration of schemes for a national federation of the Italian co-operative associations of America.”

“The Barre store and the Italian Co-operative Market in Lynn (Massachusetts), founded in 1909 by shoemakers, are under socialist direction. In accordance with the principle of orthodox socialism already quoted, no interest is paid on share capital by these associations. The profits of the store make possible a considerable reduction of the cost of goods to the purchaser, as well as substantial contributions to broad working class interests and to socialist propaganda. The Italian socialists of Barre were probably the first in New England to attempt with any success to train themselves for ultimate political socialism through immediate common ownership of co-operative business.”

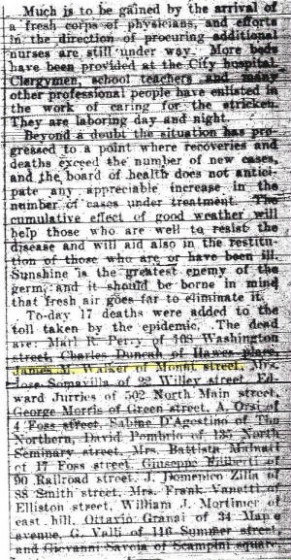

Angelo Bernardina died in Barre on October 7, 1918, from pneumonia caused by the Spanish Flu pandemic, leaving his wife and two children. He was 42 years old. At the time, he was living at 20 Vine Street.

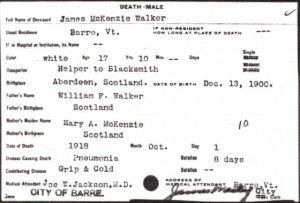

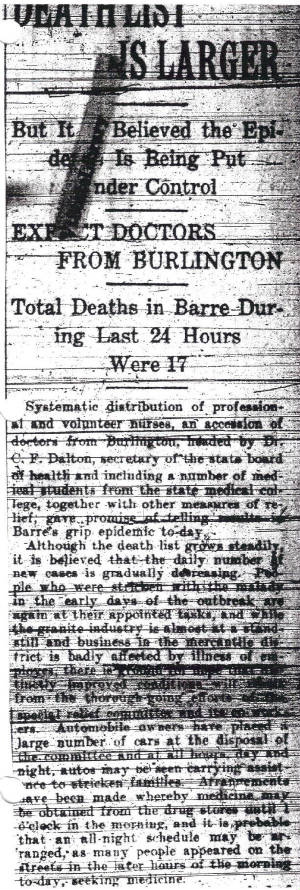

James Walker

I found the death certificate online for James McKenzie Walker. He was born in Aberdeen, Scotland on December 13, 1900. He died of pneumonia on October 1, 1918, at the age of 17. His occupation was listed as “helper to blacksmith.” It appears that he was a victim of the Spanish Flu as well, since he died only six days before Angelo did. The epidemic swept through Barre in early October, and began to subside in November. According to the death records for Barre in 1918 (posted online), 387 deaths were recorded, more than half of which occurred in October.

His parents were William F. Walker and Mary A. McKenzie. In the 1901 Scotland census, William is listed as a stonecutter, and they have two children, James and his sister Jessie. According to immigration records, they entered the US, through Boston, on September 26, 1908. By that time, they had two more sons, George and William. In the 1910 census, they are listed as living at 74 South Main Street, in Barre. William is still a stonecutter. Seven years later, his 1917 draft registration lists him living at 5 Mount Street, where he was also living in 1920, according to the census.

After that, no members of the family are listed in any accessible records. One has to assume that they left the US before 1930 (year of the last census available to the public), and possibly moved to Stanstead Plain, Quebec, just across the border from Derby, Vermont. The town was one of the centers of the granite industry in Canada. Or perhaps they just went back to Scotland. Either way, they may never have had the opportunity to visit James’s little tombstone again.

And now, Angelo and James face one another, one remembered, one forgotten.

“Some men left a reputation, and people still praise them today. There are others who are not remembered, as if they had never lived, who died and were forgotten, they and their children after them. But we will praise these godly men, whose righteous deeds have never been forgotten. Their reputations will be passed on to their descendants, and this will be their inheritance. Their descendants continue to keep the covenant, and always will, because of what their ancestors did. Their family line will go on forever, and their fame will never fade. Their bodies were laid to rest, but their reputations will live forever. Nations will tell about the wisdom of these men, and God’s people will praise them.” –Book of Sirach, New Testament, Catholic Bible