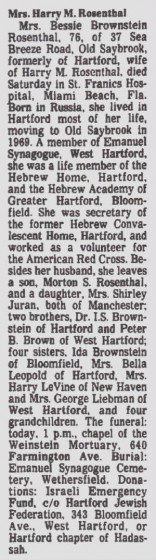

Lewis Hine caption: Newsgirls waiting for papers. Largest girl, Alice Goldman has been selling for 4 years. Newsdealer says she uses viler language than the newsboys do. Besie Goldman and Bessie Brownstein are 9 years old and have been selling about one year. All sell until 7:00 or 7:30 P.M. daily. Location: Hartford, Connecticut, March 1909.

“I remember that my mother was very proud of her work with the Red Cross blood drives during World War II. I also remember that when I reached high school, she started working Saturdays and during the holiday seasons in a very fine women’s specialty shop. And finally, I remember that her baking skills were amazing.” -Shirley Juran, daughter of Bessie Brownstein.

“I always imagined that she worked in her father’s store and that sort of thing. It’s a huge surprise. I live in Mexico, and there are kids all over the place selling things. Child labor is a huge issue here.” -Enid Dollard, granddaughter of Bessie Brownstein

“Hartford has at least one problem peculiar to Hartford. It issues licenses to sell newspapers to children between the ages of ten and fourteen years, without regard to sex. It is a good bit of a shock to the stranger to see little girls of ten selling papers after dark, with legal sanction, and in a community with a New England conscience. There’s no doubt the conscience is there, but the news-girls of Hartford are almost an institution. Girls have been on the streets for twenty years.” –The Survey, Volume 27 (1912)

When Bessie Brownstein was photographed as a newsgirl, she had been in the US about six years, according to census information. She was born on March 10, 1900. Hine took her picture sometime between March 1 and March 8, when she was still eight years old. Her parents, Meyer and Jennie Brownstein, were Yiddish-speaking Russians. They married about 1890, and had 10 children. He started out as a fruit and vegetable peddler, and later ran a small market. Bessie married Harry Rosenthal about 1918. They had two children, Morton and Shirley. In the 1930 census, Harry was listed as an advertising manager. Bessie died in Florida, on April 24, 1976, at the age of 76. I found her obituary, and that led me to her daughter, who was surprised and delighted to see the photo. But she recommended that I interview Enid Dollard, whose father was Bessie’s son Morton. Ms. Dollard was very close to her grandmother Bessie. She lives in Mexico. Other photos of Bessie may be available from the family at a later date.

Edited interview with Enid Dollard, granddaughter of Bessie Brownstein. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 30, 2010.

JM: What did you think of the picture?

Enid: It’s wonderful. I’ve already called my cousins. I knew they were immigrants, and that they had a huge family, but I never knew she sold newspapers when she was a girl. When I knew her, she was the ultimate lady, and the whole notion of her hanging around with girls who were using vile language was just too much. It was great.

JM: When were you born?

Enid: 1947. So I knew her almost 30 years. We were very close. I was the first grandchild. She and my grandfather always called me ‘Number One.’ I spent every summer with her and my grandfather until I was 16 and had all my childhood illnesses with them. I would catch the chicken pox while visiting, and my mother would say, ‘Okay, I can’t take her home. You can have her for another week.’ Her mother — my great-grandmother — lived with her until I was 13. She was this little tiny lady. My great-grandfather died when I was very little, and I don’t remember him.

JM: What was your grandmother like?

Enid: She was definitely the center of her family. Whenever there were events, everybody congregated at her house. She loved to entertain. She was a great cook. She had a bridge club and a canasta club. She would entertain her lady friends. She collected those China cups that were all different. She and my grandfather would go to New York all the time because he was a buyer. They would take me along, and we’d go to the Broadway shows.

JM: It sounds like your grandmother was fairly well off financially after she got married.

Enid: They were middle class, and they only had two kids, which was kind of unusual in those days. They had a summer cottage and things like that. They never owned a home in Hartford. They rented a seven-room flat at 101 Plainfield Street. It was owned by a Polish couple, who were like family. They also bought a large cottage at Cornfield Point in Old Saybrook. Eventually, they built a smaller winterized home on the lot next door at Cornfield Point, and left Hartford.

JM: When they were in Hartford, did they live in a Jewish neighborhood?

Enid: Yes. It was in the Blue Hills section of Hartford. After I grew up, I ran a ballet school, and I had a program for inner-city kids. We went into the public schools and auditioned kids, and one of most talented kids was living in that house. When I saw the address, I started screaming, and he thought I was a raving lunatic.

JM: When you were visiting your grandmother, what did you like to do together?

Enid: We’d shop. We loved to go to Fox’s (G. Fox department store in Hartford). We’d eat in the Connecticut Room and go to the fashion shows there. She would get all dressed up and wear white gloves, the whole bit. She was a great card player, and she taught me to play canasta. I went to Hartford College for Women, so after class, I would go over there and hang out with her and just talk. She was so proud of what her grandkids were doing.

JM: Did you ever talk to her about her family’s days in Russia?

Enid: I remember having a conversation with her once, and she talked about being a Jewish American. I said, ‘But you’re a Russian American.’ And she said, ‘No, I’m a Jewish American.’ I went to Russia many years later. I was in a cab in Moscow, and I asked the driver if he was Russian, and he said, ‘No, I’m Jewish.’ At that moment, I understood what my grandmother had said to me.

JM: When you grew up, how did your relationship with your grandmother change?

Enid: We were still very close. I would hang out at her house. She was very supportive of the ballet. They would come to fundraisers and performances. I visited them in Florida. We’d go down once a season. They would go there for six months every year. They had a whole second life down there and made many friends.

JM: The records show she died in Florida.

Enid: Yes. It was really sad. I was talking to her on the phone, and she sounded terrible. She said she had the flu. She sounded weak. So I called my father and said, ‘You’d better get down there.’ He and my mother went down and ended up putting her in the hospital, and my mother wound up catching what she had. So she came back alone. My aunt and I went down there, and then my grandmother died. My mother ended up in the hospital on the day of the funeral. It was horrendous.

JM: What do you think about the fact that she was selling newspapers on the street at the age of nine, and that her picture was used to push for the enactment of child labor laws?

Enid: I always imagined that she worked in her father’s store and that sort of thing. It’s a huge surprise. I live in Mexico, and there are kids all over the place selling things. Child labor is a huge issue here.

JM: I imagine that many people who run across these child labor photos will probably say, ‘I wonder what that kid was like.’ If you had one minute to answer that question, what would you say about your grandmother?

Enid: She was generous, warmhearted, an incredible hostess, loved family and friends, and her door was always open. She was very devoted to her husband, to her mother and her siblings, and she doted on her grandchildren. She was a great lady.

JM: What do you miss most about her?

Enid: There’s nobody around who thinks I’m as perfect as she thought I was.

*Story published in 2010.