Lewis Hine caption: Selling on Main Street, 9:30 P.M. Left to right: Joseph Magus, 10 years old, 80 Melody St. Guy Casacali, 12 years old, 31 Maple St. Morris Stein, cripple, 14 years old, 53 Sullivan St. Asked policeman on corner where they were selling, how late they stayed out at night. He answered evasively; “Ain’t supposed to be out after nine o’ clock.” Location: Rochester, New York (State), February 1910.

“His whole life, he had all kinds of jobs, along with his regular job. He always picked up little part-time jobs, just to keep the family above water. We had a big family, and he always took care of us.” -Guy F. Casaceli, son of Guy E. Casaceli

“In the country the darkness of night is friendly and familiar, but in the city, with its blaze of lights, it is unnatural, hostile and menacing. It is like a monstrous vulture that hovers, biding its time.” -playwright and novelist W. Somerset Maugham

“Why do we allow little children to work at any age, both night and day, as newsboys, bootblacks and peddlers in the essentially dangerous environment of the street? Such employment offers but a gloomy future – the useless life of the casual worker. There is no better position to which it leads, no chance for the discovery and development of ability, and no reward for good service. It seems incredible that we have been so engrossed with throwing safeguards about the children in regular industries that we have altogether neglected the street worker, for the arguments against child labor in factories, mills, mines and retail shops apply with even greater force to the work of children on our city streets.” -from Child Labor in City Streets, by Edward N. Clopper, National Child Labor Committee, 1912

**************************

It’s a typical February night in downtown Rochester. Snowflakes cling to the coats and hats of anyone who decides to brave the cold. A trolley goes by on a slushy street, perhaps some factory workers going home among the passengers. Three newsboys, 10, 12 and 14, stand on a sidewalk, probably wishing they were also on that bus and heading for their homes. Lewis Hine surveys the scene and wonders, “Who in his right mind would be looking to buy a newspaper now?” But the more important question Hine had on his mind was, “What are these children doing out here at 9:30?”

We may never know what happened to 10-year-old Joseph Magus, and 14-year-old Morris Stein, whom Hine describes as crippled. My research turned up little of value. But 12-year-old Guy Casaceli left an easy trail to follow. I found his WWI draft registration. He appears in the 1930 and 1940 censuses, and he is listed in the Social Security Death Index. And then I came across the 2008 obituary of one of his daughters, who was survived by a brother, Guy, who lives near Rochester. I called him, and he had never seen the famous photograph of his father.

Guy Ernest Casaceli was born in Lipari, Italy on October 28, 1897, the son of Felix (or Felice) Casaceli and Mary Lombardo Casaceli. Immigration records for the family are sketchy. In the 1915 New York census and the 1920 US census, Felix’s immigration year was given as 1903 and 1902, respectively, but I could not confirm the date in the passenger lists for Ellis Island. Felix is listed in the Rochester directories as early as 1904.

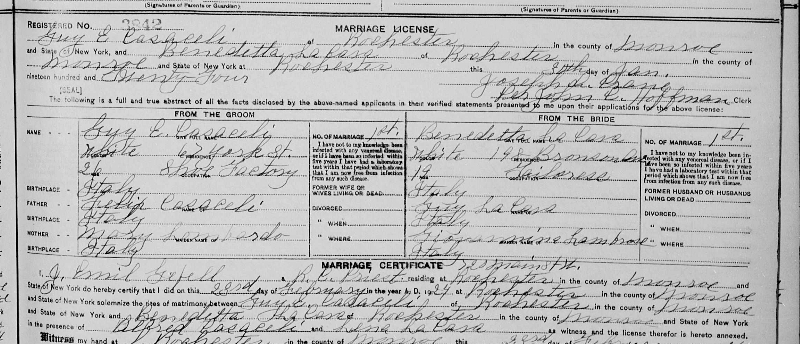

Guy was working as a shoe cutter as early as 1918, and continued to do that at least until 1938, according to the census and city directories. He married Benedicta (called Bertha) La Cava in Rochester on February 23, 1924. He was 26, and she was 19. Guy passed away in Rochester in January of 1974, at the age of 76, less than a year after Bertha died. They had seven children.

Lewis Hine caption: Newsies in cellar-room of a paper office in alley back of Main Street, waiting for evening papers, 4 P.M. Conditions here vile. Location: Rochester, New York (State), February 1910.

Edited interview with Guy F. Casaceli (GC), son of Guy E. Casaceli, Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on November 8, 2012.

JM: What did you think of the photo?

GC: It was very good. I liked it. I was surprised that he was selling newspapers at that age. His whole life, he had all kinds of jobs, along with his regular job. He always picked up little part-time jobs, just to keep the family above water. I remember him working as a clerk at Dawes Drugs. We had a big family, and he always took care of us.

JM: With him working so much, you probably didn’t see him very often.

GC: I didn’t. He was a working fool, I tell you.

JM: Did you know that he lived at 31 Maple Street when he was a boy. That’s what the caption in the photo said.

GC: I know that he lived in that area. His mother had a little grocery store. The first place I remember us living at was at 65 York Street.

JM: What was his father do for a living?

GC: He was a cooper. He made barrels in a factory.

JM: What was his father’s name?

GC: Felix, and his mother’s name was Mary. Her maiden name was Lombardo. She was related to Guy Lombardo. Her brother was Guy Lombardo’s father, so she was Guy Lombardo’s aunt. She used to correspond with him.

JM: In the 1930 census, your father was a listed as a shoe cutter in a factory.

GC: Yes, I know that. Later, he got a job with the city of Rochester. He worked for the water works. It was an office job. (In the 1940 census, his job at the water works was listed as janitor.)

JM: Did your mother work outside the home?

GC: Not that I ever knew. She had plenty of work to do in the house. She had seven children.

JM: What was your mother’s name?

GC: Benedicta, but she was called Bertha.

JM: When did your parents marry?

GC: I don’t know, but I would guess about 1923 (1924). Felix was the first child.

JM: Did your parents own a house?

GC: Yes, when we moved to 65 York Street. It was a two-family house. First we lived in 67, and then we moved to 65, and my grandmother and her family moved into 67. Most of the people in our neighborhood were Italian.

JM: When your father did have time, what did you like to do with him?

GC: We used to go pick dandelions a lot. My mother would cook the greens. When apple time came, my mother would go out and climb the trees and pick apples.

JM: Did you graduate from high school?

GC: Yes, Madison High School. Then I got a job at Kodak, and at night, I went to RIT (Rochester Institute of Technology). I graduated from there. Kodak paid for it. I put in a lot of years at Kodak. I was a toolmaker.

JM: Did any of your siblings go to college?

GC: My big brother, Felix, graduated from RIT. Then he moved to New York City. After I got married, I was living in Rochester, and then my wife and I moved to Avon (New York) about 1970. I commuted from there to work, which was about 18 miles. I retired in 1991.

JM: When your father retired and got older, was he still in good health?

GC: Yes. He would come up to the house and work around the yard. He was a go-getter.

JM: What was your father like?

GC: He just worked hard all the time. He didn’t smoke or drink, though he might have had a beer occasionally.

JM: Your father was born in Italy. Did he ever talk to you about his life when he was a boy?

GC: He never talked about it. My wife and I went to Italy on vacation once and saw some of his family. They were still around. He was brought up on an island off the coast of Sicily, but I don’t remember the name of it. (It was Lipari.)

JM: Did your parents speak Italian?

GC: Yes. And we spoke it with them when we were kids.

JM: How well off was your family when you were growing up? Were you relatively poor?

GC: We got by. My father always provided us with enough food. We didn’t have a car. We would take the bus. You could get a whole week’s pass for one dollar.

JM: What did your father die from?

GC: He had cancer. I thank the Lord that he was my father, because he always provided for us. He lived for us, not for himself.

Guy Ernest Casaceli: 1897 – 1974

The following are excerpts from a 1913 report by Zenas L. Potter, published in the bulletin of the New York Child Labor Committee:

In the fund now before the public, little or nothing showing the relation of street trading to the school is to be found. The moral effects of street trading have been studied. We have known that astonishingly large numbers of newsboys and bootblacks find their way into juvenile courts and reformatories. The poverty side of the question has been investigation and reported on. But we have had little information as to the effect of street trading on the boys’ school work. During the past year, therefore, the New York Child Labor Committee made an investigation of this phase of the question in three Western New York cities — Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse.

School records of newsboys were obtained directly from their teachers. In Buffalo the records of 230 boys-about one-fourth of the newsboys in the city-were secured. Eighteen per cent were reported as truants. Twenty-three percent stood poor or very poor in both attendance and deportment. In scholarship twenty-eight per cent were below grade, while but nineteen per cent of all the children in the Buffalo school, with the largest attendance of Italian children-the best basis for comparison obtainable-were below grade in their work.

In Rochester records of 130 newsboys were obtained. Here but five per cent were truants, and but ten per cent were poor in attendance, due to excellent enforcement of the Compulsory Education Law. Twenty-one per cent, however, were poor or very poor in deportment, and twenty-nine per cent failed in scholarship, as against fifteen per cent who failed of all the children in the school having the largest percentage of foreign children.

One hundred and eighty newsboys’ records were studied in Syracuse. Nine per cent were reported as truants, and sixteen per cent were poor or very poor in attendance. In deportment twenty-eight per cent were below standard, and in scholarship, thirty-five per cent, over one-third of all the newsboys failed, as against twenty-four per cent who failed, of all the children in the school having the largest per cent of foreign attendance.

Besides gathering these facts, the Committee studied the boys in the truant institutions of these three cities. In Syracuse forty per cent of the boys in the truant school had been newsboys. In the Buffalo truant school, forty-six per cent were former street traders. Rochester maintains no truant school, but a special class for truants and incorrigibles. At the time of my visit there were sixteen boys in this class. Fourteen were newsboys or bootblacks.

What conclusions are we warranted in making from these facts? I believe we are justified in saying, in the first place, that truancy among newsboys is abnormally large. By truancy is meant not only absence from school, but absence without a legitimate excuse. The actual percentage of newsboys who are truants in each city is intimately bound up with the character of enforcement of the school attendance laws. In Buffalo eighteen per cent of the newsboys were reported as truants. It would seem, however, that what truancy there is in Rochester is confined largely to street traders, for of the truants who found their way to the truant class, eighty-five per cent were newsboys or bootblacks.

The second conclusion suggested is that street trading tends to make boys ungovernable in school. In support of this conclusion, besides the fact that approximately a quarter of the newsboys stand poor or very poor in deportment, as shown above, is an almost universal opinion among principals and teachers in these cities that newsboys are difficult to manage.

The third conclusion which our facts go to prove is that street trades have a direct and detrimental effect on the scholarship of the boys who engage in them. The facts show indisputably that the per cent of the newsboys who fail in their school work is from once and a half to twice as great as the per cent who fail of all the children in the schools having the largest proportion of foreign attendance — the best basis for comparison which was obtainable.

In reason, these are the conclusions to be expected. It is only natural that a newsboy, when he finds he can make monopoly profits on the streets during school hours, should incline to truancy. It is expected that the lack of restraint which he experiences on the street will make him uneasy under restraint in school. Moreover, it is reasonable to suppose that when the boy gets out amid the excitement of the street, and first experiences the joy of earning money and of spending it, his center of interest will be transferred from his lessons to his work, and his school work will suffer.

I do not wish to be misunderstood. I neither claim that all newsboys fail in their school work, nor that when a newsboy fails, street trading is the sole cause of his failure. A boy with a good heredity and environment will often overcome the disadvantages of street trading. I do claim, however, that those disadvantages are real, not imaginary, and that with the class of boys who predominate in street trading, they are often the influence which, added to other bad conditions, lead to the boys’ failure in school. We cannot in a day remove dirty, overcrowded homes, ignorant parents, or poverty; but we can and should protect boys from the injurious effects of the street trades.

*Story published in 2013.