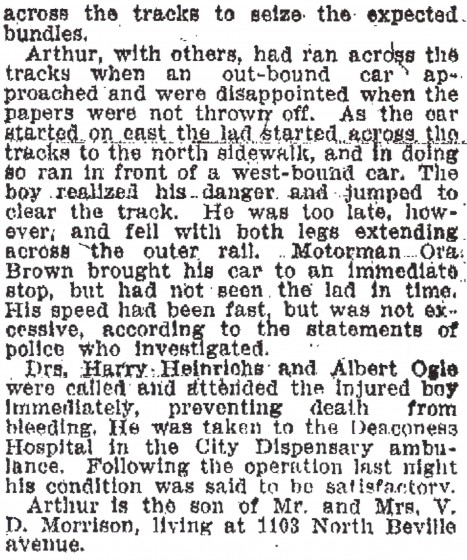

Lewis Hine caption: John Howell, an Indianapolis newsboy, makes $.75 some days. Begins at 6 a.m., Sundays. (Lives at 215 W. Michigan St.) Location: Indianapolis, Indiana, August 1908.

“In the evenings, he would go play pool, and me and my brother would go with him. He was a great pool player. He would play for a dollar or two a game, and he’d let me carry the money. We would come home $80 or $90 ahead.” -Thomas Howell, son of John Howell

The first thing that caught my eye in this photo was the shadow of Lewis Hine and his camera. This is one of only several photos where that happened. The second thing that caught my eye was how large the newspapers looked under young John’s arm. He was only nine years old.

Right away, I wanted to know where he was standing, and what the location looks like 104 years later. In the online Indianapolis directories for the early 1900s, I found the location of the Danbury Hat Company (see vertical sign), and the Douglas Shoe Co. (on the corner across from John). Using Google Maps, I located the exact spot where John was standing. He was facing west, at the corner of West Washington Street and North Meridian Street. New buildings have replaced old ones.

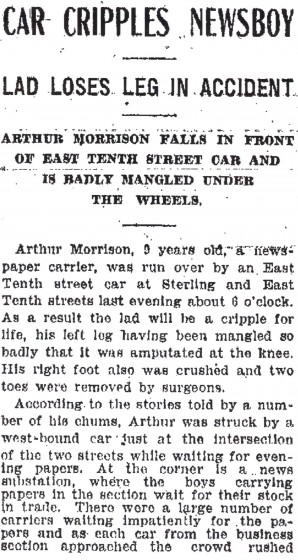

Lewis Hine took close to a thousand pictures of newsboys, newsgirls, messenger boys, and other children involved in the street trades. His employer, the National Child Labor Committee, was concerned about young children being subjected to risky, dangerous and unhealthful conditions in a variety of situations, not simply mills and factories. The article below was published in the Indianapolis Star, 15 months after John was photographed. His family probably heard about it.

Six years later, an article about this issue appeared in Public Welfare in Indiana, published by the Indiana Department of Public Welfare.

“In seeking to arouse public interest in the newsboy or messenger boy, the social worker runs up against two opposing forces – the sentimental man who says that the street life is a good training for a boy, instancing men of his acquaintance who have become successful business men starting out as newsboys or messenger boys; and secondly the newspapers who, because of the competition of other papers, use all their powers to persuade boys to become newsboys and scout the idea that any boy could be hurt by such work.”

“It is a fact that over 50 per cent of the delinquent boys who come into our juvenile court, and I venture to say the majority of juvenile courts, are boys of some street experience, the majority being newsboys. The messenger service in times past contributed a good share of boys, but the percentage is now very low. This is due to several causes, the principle one, I believe, being the enforcement of the law which prohibits the employment of a (messenger) boy under 16 after night.”

“Edw. N. Clopper in his various books and pamphlets on street trading has brought out very strongly the dangers which surround the messenger boy who works at night, the association with gambling, drinking and prostitution. Even in day messenger service the boy is brought in contact with those vices but not to such an extent. In a number of states, no boy under 21 is employed in messenger service after night.”

“Although we find some regulation of the working hours of the messenger boy, we find none for the newsboy. He may rise, and often he does, at five in the morning, and sells papers until late at night. Even if he is a school boy, he may rise early, sell before school and after school and get so little sleep that he is dull and sleepy in school and often a truant. On the street he may work, and often does, twelve or fourteen hours. He is exposed to all kinds of weather, his food is uncertain and insufficient, and he is in constant physical and moral danger. He should be protected by the state, yet is not, because street trading is not included in the child labor law, and the newsboy is not regarded as a wage earner but as a little merchant.”

“Lieut. Corrigan of the Indianapolis police force has made an extensive study of street trading. His attention was called to the number of newsboys who were injured and maimed for life by street accidents.”

John David Howell Jr. was born in Ohio on July 29, 1899, the third child of John David Howell Sr. and Flora L. (Robinson) Howell, Illinois natives who married in about 1895. According to the 1900 census, the family was living in Gibson, Ohio, where John Sr. was a clergyman. The Indianapolis directories indicate that the family moved to the city about 1905, where John Sr. was a city solicitor for several years, and also worked as a collar maker.

But a few years later, something must have gone wrong with the family situation. According to the 1910 census, John Sr., John Jr., and his older brother Kenneth were living in a boarding house in Jackson, Michigan, where John Sr. worked as a newspaper reporter and son Kenneth worked as a newsboy. John was attending school. But wife Flora and 12-year-old daughter Alice did not live with them. In fact, I could not find them in the census at all. According to a 1913 article in the Indianapolis Star, John was convicted of child desertion. He never appeared again in the Indianapolis directories or in the census.

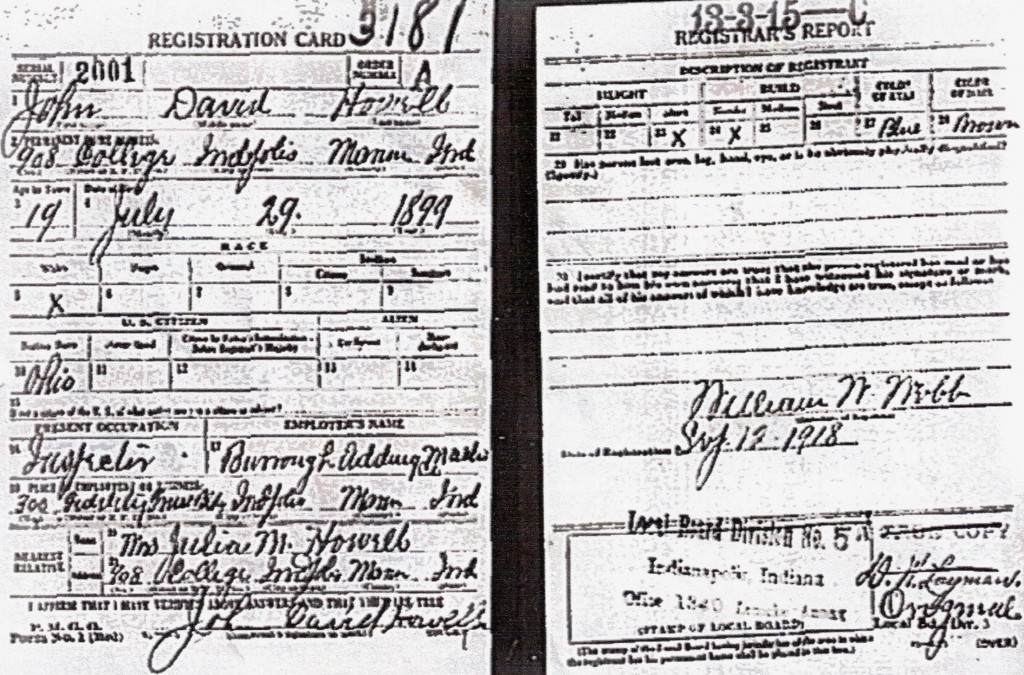

By the time John Jr. registered for the draft in 1918, he was married to Julia, and he was an inspector for the Burroughs Adding Machine Company. His mother Flora was living with them. According to the 1920 census, John and Julia were living at 908 College Avenue, in Indianapolis, and had one child, also John (called Jack), born in 1919. He was born in Canada. John’s son confirmed this, but he does not know why his father and mother were in Canada. John’s mother Flora was working as a private duty nurse, and lived nearby. She was listed as a widow.

In 1930, John and Julia were living at 2332 Parker Street, in Indianapolis. He was still inspecting adding machines for Burroughs. Their second child, Alice, had been born in 1921. By 1940, they were living in Phoenix, Arizona. They had two more children, Patrick and Robert, born in Arizona about 1934 and 1937. John was still an adding machine inspector. His mother Flora, 69, still lived in Indianapolis, and still worked as a private duty nurse. She passed away in 1955, and is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, in Lebanon, Indiana, about 30 miles from Indianapolis. By 1943, the Howells had moved to Tucson, and had twin boys, Jerry and Thomas.

John Howell died in Tucson in November of 1982, at the age of 83. Wife Julia died seven years later. I located and interviewed John’s son Thomas, who lives in Tucson. He had never seen the photograph of his father. He was not able to find any pictures of his father.

The following are edited excerpts from my interview with Thomas Howell, son of John Howell. Interview conducted on August 4, 2012.

“I was born in Tucson in 1943. I was a twin; the other was named Jerry. My parents also had Jack, Alice, Patrick, Robert, and a stillborn child.”

“He worked most of his life for the Burroughs Adding Machine Company. He was trained by them in Indianapolis, and later, the company sent him out here to Tucson. By the time I came along, Mother and Daddy were in their forties. He worked for Burroughs until sometime in the 1950s or 1960s. They let him go before he retired, without any benefits. He had carpal tunnel syndrome, and that’s why they let him go. So he started an adding machine and service supply business and ran it himself until he retired. He worked on all types of adding machines. He had a big garage a couple of miles from the house, and he operated his business out of there. He made a good living cleaning and adjusting adding machines, and selling the ribbons.”

“He always drove Chrysler cars. He always bought a station wagon. They had a house on Broadway when I was growing up, and then they moved to 51 West Wetmore Road. When he would come home from being on the road, he would bring us a load of cantaloupes and watermelons, and he would always buy us cases of Pepsi or Coke. He said things were too expensive in Tucson, and he could get good bargains out of town.”

“When school was out, he would take me and my brother on the road with him for seven or eight days at a time. We’d go all around the state, and he would work on adding machines. We would help him. We didn’t stay in any big luxury hotels. The ones we stayed in always had a bath down the hall. But we always ate good. In every town, he’d have seven or eight adding machines to work on. He also bought and sold adding machines. If he found a used one, he would fix it up and sell it to some little store that needed one, and he would give them a guarantee and a service contract. Daddy was smart.”

“In the evenings, he would go play pool, and me and my brother would go with him. He was a great pool player. He would play for a dollar or two a game, and he’d let me carry the money. We would come home $80 or $90 ahead. I remember that in the towns we would go to, they had a lot of Chinese and Mexican markets. They all loved Daddy, because he was good to them.”

“After he retired, he and Mom lived in a trailer court. The last couple of years of his life, he was living in a nursing home, and my mother lived in a separate room in the same nursing home. He finally had a heart attack. He never drank, but he smoked Pall Malls up until the day he died. My mother died a couple of years later. She was the kindest, sweetest, most lovable person I’ve ever known. She was a Gold Star Mother, because Jack died in WWII.”

John Howell: 1899 – 1982.

So what happened to Arthur, the newsboy who was run over by a street car? I am happy to say that he did well. He moved to Cleveland, Ohio, and in 1922, started Breath-O-Life Oxygen Inc, which manufactured a device that helped people with breathing difficulties. He was the president of the company, and received (posthumously) both a US patent and Canadian patent for the device. He was married, but had no children. He died in 1959. I found one descendant, a nephew who lives in California. He knew very little about him. All he could remember was that his Uncle Arthur visited his family in California several times and “drove a fancy Cadillac.”

*Story published in 2012.