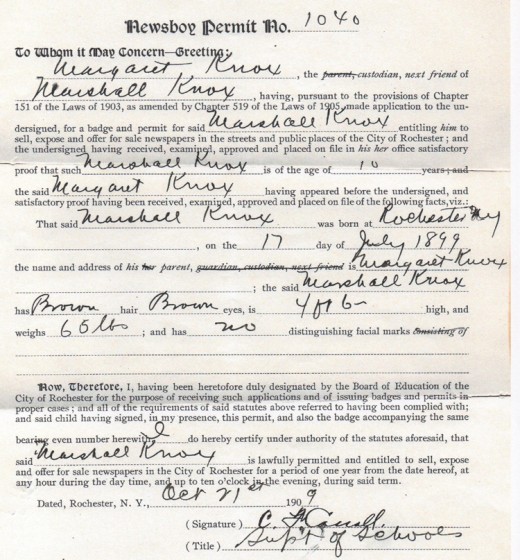

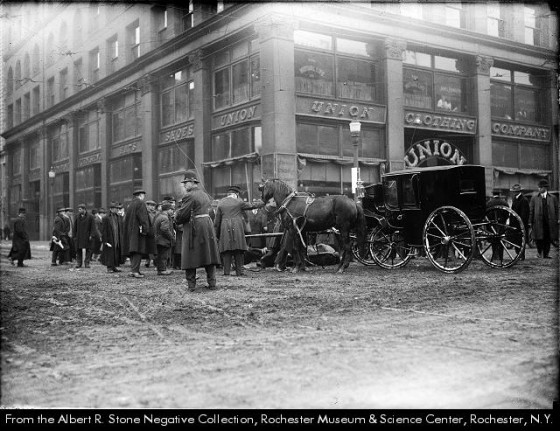

Lewis Hine caption: Newsie on Main St. at 2 P.M. Said “our class did not have any school this afternoon.” Marshall Knox, 10 years old, 23 Hamilton Street. Location: Rochester, New York (State), February 1910.

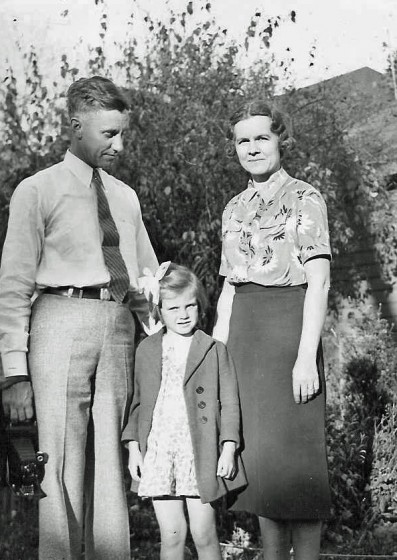

“He was very distinguished looking. When he was almost 90, he had a lot of shocking white hair.” -Marianne Hesselberth, daughter of Marshall Knox

Marshall Knox was 10 years old when Hine found him standing on the sidewalk, with the Union Clothing Company providing a distinctive background at the corner of Main Street and St. Paul Street.

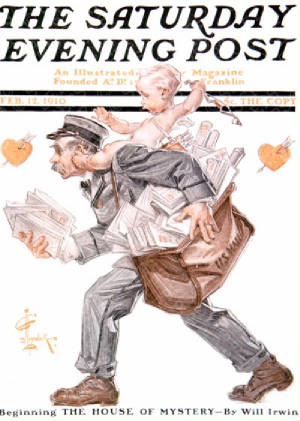

My research shows that he was selling the February 12, 1910, edition of the Saturday Evening Post, which at that time was a weekly magazine. He surely would not have noticed the bizarre coincidence contained therein. Starting on Page 10, there was an article called “The Limitations of Reform,” written by Joseph W. Folk. The author mentioned child labor. The following is a brief excerpt.

“Reform is progress and, notwithstanding all opposition, there has been much progress in the last few years. The war being waged against corruption, the primary laws and anti-lobby laws, race-track gambling laws, public service regulation laws, the child labor laws, are all evidence of the struggle for better things. Where will it end? Where should it end? These questions are being asked everywhere. The fight against privilege should never end, it must be kept up constantly.”

In February of 1910, The National Child Labor Committee sent Lewis Hine to the Upstate New York cities of Rochester, Buffalo, Syracuse, Utica, Schenectady and Albany, to investigate child labor among newsboys and street messengers. His visit followed up on some sharply worded reports 13 months earlier at the annual convention of the Committee. Here are some excerpts.

George A. Hall, Secretary of the New York Child Labor Committee: “The following are, in my judgment, the weak points in the New York law (regarding newsboys): The minimum age of ten is absolutely bad; it should be at least twelve. Our Committee stands for the twelve-year age limit. The night-closing regulation is another bad feature. I can see no reason why boys should be permitted to work on the street until ten o’clock when the law requires boys in stores to stop at seven and in factories at five. We urge at least an eight or nine o’clock closing hour.”

“Improvement is to be recorded in the enforcement of the law regulating the sale of newspapers by young boys in cities of the first and second class. This is particularly noticeable in New York, Rochester and Troy, where badges indicating that the holders are legally licensed to sell papers, are beginning to be more generally worn by newsboys.”

Mrs. E. J. Bissell, Rochester, N. Y.: “Rochester is a city of 200,000, with 700 newsboys. We have this law in New York State, and up to a year ago, the board of education did not even know they were responsible for issuing badges. We found perhaps one boy in thirty, in some cases one in fifty, with a badge. The Committee on Child Labor visited first the board of education and had a serious talk. The board promised to co-operate with the police commissioner or to get his assistance.”

“The policemen themselves had had a fee of twenty-five cents for issuing every badge, so they were disposed to give no help, and the only way even under our good law was through a mass meeting called for another purpose, a mass meeting of about 1200 women. The subject was brought up, the city was districted, and each woman was asked to consider herself a member of a Vigilance Committee in her hours of shopping. Every woman whose business took her to the city at seven or eight o’clock in the morning was asked to co-operate and to follow out one little plan. The moment a boy was found, or two boys, in some cases there would be five before you would walk a hundred feet, that woman would get to the nearest telephone and say to the board of education and the police department, I found so many boys at such an hour at such a place.”

“It took but five days to send in such a fire to both these departments that the school superintendent and then the president of the board of education called up the chairman of this committee and wanted to know what they could do in the matter, and arranged for a meeting. We had our meeting and called attention to the fact that badges should be issued, and they asked for two weeks in which to secure new badges and enforce the law, and of course, for two weeks we stopped telephoning.”

“At the end of two weeks the badges came and the superintendent had, in the meantime, called up each principal. The principal was to send his boys desiring badges to the board of education. The truant officer came there, also the chairman of the Child Labor Committee, and each child had an ordinary little card which had to be signed, and the badges were issued and the children were instructed to wear them. For possibly three or four weeks we saw a great many badges on the streets, and then the badges disappeared gradually. We felt we ought to begin our campaign over again. We found one little boy four times in ten days, a child of seven selling papers and pleading for money – he had ‘lost twenty-five cents,’ and, of course, he was obtaining money.”

“We secured the help of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, and we made this a test matter. As the outgrowth, the board of education appointed one truant officer, the commissioner of police appointed another policeman, and he then districted the city, and those two men were required to report every child found. In the new campaign, they took away, in three days, fifty badges from boys. No badge was reissued until the parents, at least one parent, accompanied that child back to the office of the board of education. That had a very good effect on the child as well as on the parent. Many of the men became interested and today I think we have an unusual city.”

“Just before I left, I had a report from a business man, saying that he had one serious charge to make against the Child Labor Committee of Rochester. He said that where formerly anyone, at seven o’clock or six o’clock in the morning, could find any number of small boys selling papers, now he had to walk two blocks before he could get one at an early hour.”

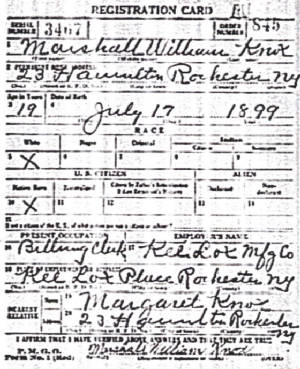

After finding Marshall in the census, and then finding his World War I draft registration, I tracked down his death record and obituary, which led me to his daughter, Marianne Hesselberth, who lives just a few miles east of Rochester. She had never seen the famous photo of her father, though much of Hine’s work is displayed or archived at the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film, which is in her hometown.

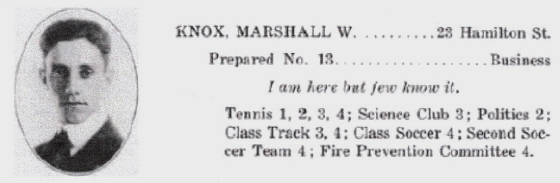

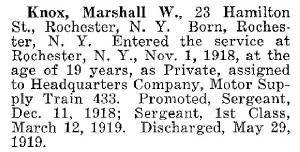

Marshall William Knox was born in Rochester on July 17, 1899. His parents, Charles and Margaret, had only one other child, a daughter who died at the age of two. They married in about 1898. Marshall married Laura Towsley in 1930, and they had one child. An accountant for many decades, he passed away in Rochester on February 26, 1989, 79 years to the month after he posed for Lewis Hine on a cold winter day. He was 89.

Edited interview with Marianne Hesselberth (MH), daughter of Marshall Knox. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on November 5, 2012.

JM: What was your reaction to the photo?

MH: I thought it was great. My father never said anything about it.

JM: Did you have any idea that your father was a newsboy at the age of 10?

MH: No.

JM: What were his parents’ names?

MH: Charles and Margaret. Her maiden name was Marshall. My father was named after her.

JM: What was his father’s occupation?

MH: He was a shoemaker. I think he worked for a shoe company.

JM: When did your father marry your mother?

MH: In 1930. He married Laura Towsley. She was from Rochester.

JM: How many children did they have?

MH: Just me. I was born in 1932.

JM: Where were they living at the time you were born?

MH: 125 Edgemont Road, in Rochester. It’s just a short walk from the Erie Canal and the city limits.

JM: Did they own the house?

MH: Yes. It was a single-family house, right near the University of Rochester.

JM: What was your father doing for a living then?

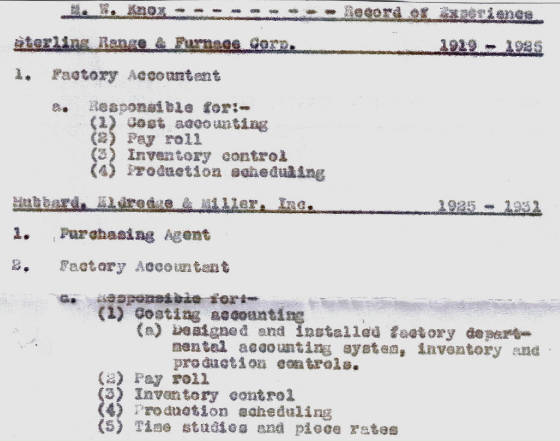

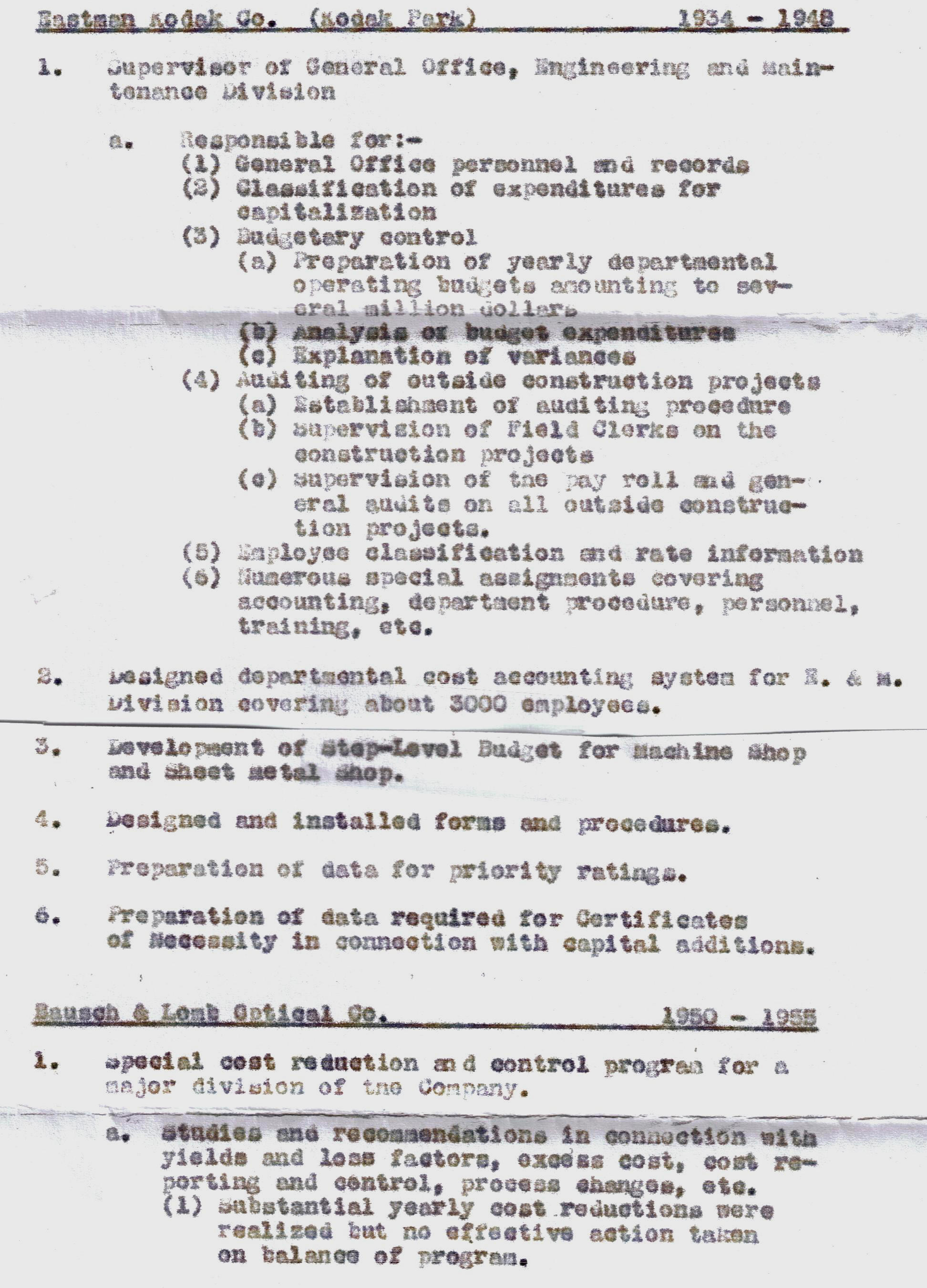

MH: When my parents were first married, he was an accountant for a furniture store (Hubbard, Eldredge & Miller), which folded during the Depression. Then he was at Kodak about 14 years, and then a few years at Bausch & Lomb. He always was an accountant.

JM: Did he go to college?

MH: He went to an accounting school in Rochester for about a year or so. He wasn’t a CPA.

JM: Did he drive or walk to work?

MH: He always drove.

JM: Did you live in the house all the years you were growing up?

MH: Yes.

JM: Did you have a lot of friends in your neighborhood when you were growing up? Were there a lot of children to play with?

MH: Yes, quite a few. Some of them had families that were connected with the university or the Strong Memorial Hospital.

JM: When did you leave home?

MH: I went away to college. I spent two years at College of Wooster, in Ohio, and I graduated from St. Lawrence University in Canton (New York). I majored in business administration. Then I started working as an underwriter for Travelers Insurance Company. When my husband started a business, I was his bookkeeper.

JM: Have you lived in the area all your life?

MH: Yes, except for one year when my husband was in the service, and the four years I was in college.

JM: Do you have children?

MH: Yes, David, Mary and Susan.

JM: Have they seen the photo of your father?

MH: Yes. Susan looked it up on the Internet and found it on six websites, and Amazon was selling a copy of it. She said to me, ‘I wonder what Grandpa would think if he knew he was on the Internet.’ David could see that his grandfather was selling the Saturday Evening Post, so he went online and looked it up and found out the date of that issue.

JM: Why did your parents have only one child? Was it a biological reason?

MH: It was because of the Depression, I think. And my mother taught in Rochester for 42 years. When you got married in Rochester back then, your salary was cut in half if you were a teacher. A good share of her friends, and some teachers had only one child, or didn’t get married. She probably had a more secure job than my father had. Also, my mother was already 34 when she got married. My dad was 31.

JM: Were times tough for your parents during the Depression?

MH: I’m not sure. I was pretty young then. I know that both of my parents were helping to support their mothers.

JM: Did you know your father’s parents?

MH: Yes. For about 20 years, or perhaps longer, my father’s parents didn’t live together. But as they got older and were not well, they got back together, and for another 20 years they were very devoted to one another. I think it was a hard life for my grandmother, financially, because of the separation from my grandfather. She worked hard, and she didn’t drive. But she had a lot of friends. Her church was down at the corner, and a lot of family lived in the area. Between the family, the church and her work, she got by.

(Per the US and New York censuses, Marshall’s father was confined at the Rochester State Hospital for the Insane for at least five years, and might have been a patient there when Marshall was photographed by Hine. His father lived alone in a boarding house for 10 or 15 years after he left the hospital. When I informed Ms. Hesselberth of this, she said that she recalled hearing that Marshall’s father had a serious ear infection which led to a change in his behavior, but she could not be sure this was correct).

JM: What did your father like to do when he wasn’t working?

MH: He golfed and bowled, and both my parents were bridge players. Later in my life, I played golf with him. He was an air raid warden during the war. Everyone had to turn off their lights then. I still have his stick and his helmet. He belonged to the Masons and the American Legion, and he was very involved in the Presbyterian Church.

He was close to his childhood friends all of his life. He often spent time with them and their families on holidays, and went on picnics and trips with them, and sometimes children were included. Even today, the younger generations get together. I celebrated New Years Eve with my parents, starting when I was just three month old, probably so they wouldn’t need a babysitter. We visited relatives a lot. Five generations of both my parents’ families have lived in Rochester. I had many cousins in the area, but I had some from as far away as Albany, Wisconsin and Canada.

JM: How long did your parents live in the house you grew up in?

MH: About 50 years. Then they lived in an apartment for a few years, and after that, they moved into a retirement home.

JM: Were they in good health in their later years?

MH: They didn’t move into the retirement home till my mother was 90. She was a little older than my dad. My father died just short of being 90. He had never been sick a day in his life, until he had a stroke when he was 89. He died about seven weeks later. My mom died in a nursing home at the age of 96.

JM: What was your father like?

MH: He was very distinguished looking. When he was almost 90, he had a lot of shocking white hair. He was somewhat quiet, and very gentle, but he was stern in ways. You knew when he said no, that was it. When I got out of college, I wanted to move in with friends. He told me that as long as I lived in Rochester, I should live at home. That’s what he thought, and that’s what I did, until I got married.

JM: What do you think about the fact that Hine took a picture of your father so could use it to persuade people that children like your father should not be newsboys at that age?

MH: I was surprised that he was only 10 when he was selling on the street. I can’t imagine my grandmother letting him walk downtown. I always thought that she was quite protective, especially because Dad had only one sibling, a sister who died at the age of two, so he was really an only child. I know what downtown Rochester is like now, and you wouldn’t want your child there at all. It’s an entirely different situation.

JM: In many ways, it’s not that different. A lot of cities 100 years ago could be pretty dangerous for children. There may not have been a high level of drug dealing and stuff like that going on, but there still would have been a lot of unsavory characters and a lot of gangsters, even in places such as Rochester.

MH: I worked in the downtown for many years. It was great, but all those stores and restaurants were there. Now most of them have moved out, so it is more dangerous now.

JM: But when you’re an adult, and you are working downtown, then or now, there are things that you’re going to be cautious about. But little children aren’t very aware of that, so they are more vulnerable. There are a lot of temptations. That is what Lewis Hine was concerned about. But in the photo, your father was nicely dressed. He had a nice hat and a nice coat. His clothes fit him. His face looks clean. He looks like he’s okay. Obviously, he accomplished a lot in life despite being a young newsboy. Others did, too, but many did not. A lot has to do with family upbringing, and it sounds like he was raised well.

MH: He was a great father. He was very understanding. I’m glad that I was his daughter.

Marshall Knox: 1899 – 1989

Despite having to work as a newsboy at age 10, Marshall Knox’s accomplishments turned out to be impressive. After his retirement, he listed all of his adult employment, and included detailed descriptions of his tasks and responsibilities. Click on the images below.

*Story published in 2012.