John Vachon caption: The Misch family, tenant purchase borrowers. Labette County, Kansas, November 1940.

“I remember Mom and Dad laughing about it. The photographer dropped by one morning and wanted to take a picture of the kitchen cabinets we had just put in. My brothers were out working with Dad in the yard and the barn, and they were all muddy. I was probably still in bed, so they had to get me up. We were not prepared for it.” -Delores Miksch Morarity

“It seemed like we were up every morning at four o’clock, milking cows and feeding the hogs. You had to get it all done before you went to school.” -Dale Miksch

“I don’t remember Grandpa whining about what he had to go through during the Depression. I knew people who lived in that era who were always telling you how bad it was, but Grandpa would just tell me about the things he did to get by, and that was why we were doing the same things now. -Donald Hellwig, grandson of Forrest and Ruth Miksch

Forrest Eldon Miksch and Danzil Ruth Pefley were born and raised in Liberty Township, a farm community near Oswego, Kansas, a small city in Labette County. They married on November 7, 1927. They had met at a “box supper,” a popular custom in the Midwest (see below for more information about the box supper). The couple settled into a rented farm next door to Forrest’s parents, Charles Amos Miksch and Catherine Adelaide (Addie) Carton Miksch. Ruth’s mother, Stella Mae (McLin), died in 1928, and her father, Daniel Pefley, remarried and lived in nearby Parsons.

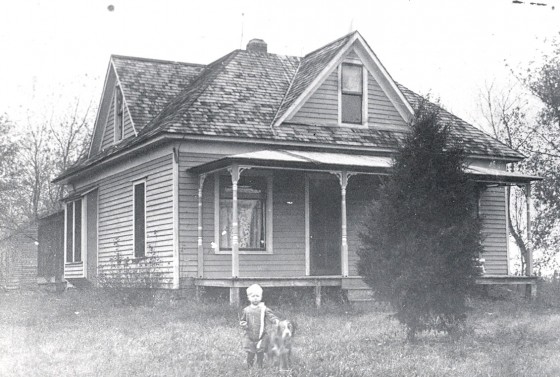

In 1940, Forrest and Ruth, now with four children, received a loan from the Farm Security Administration, a federal agency created by the Franklin Roosevelt administration in 1937. The FSA employed a staff of photographers whose assignment was to document the work of the agency. One of those photographers, 26-year-old John Vachon, showed up at the Miksch farmhouse one morning in November. It was probably a Saturday, because in the photograph the children were at home and the family was not dressed in typical Sunday garb. He took an additional picture, showing Mrs. Miksch in the kitchen.

Vachon would later become one of America’s best known documentary photographers, working for Look Magazine, Life Magazine and the United Nations, among many others. Forrest and Ruth used part of the loan to purchase the farm they were renting, and subsequently operated the farm successfully for 35 years. All four of their children attended post-secondary educational institutions, married, and raised children of their own, one of whom is Donald Hellwig, who has owned the farm since 1975.

In his caption, Vachon didn’t include a first name, and misspelled the last name, but I confirmed who they were in the 1940 census, and within days, had spoken to children Dale and Dolores, and grandson Donald, the one who owns the farm. Their interviews, and many family photos that they provided are included in this story.

**************************

Box suppers: Box suppers were affairs often held to purchase supplies for the local school. Each girl attending would bring a box supper, and boys would bid on them, without knowing which girl brought which box. The boy who made the winning bid on a box got to eat whatever was in it with the girl that brought it. Boys were often asked to bring pies or cakes to sell. As the family tells it, one of Ruth’s friends knew Forrest, and wanted Ruth to meet him. She told him to go to the event, and when he got there, she told him which box belonged to Ruth. He bid on it and won.

Below is an article that appeared in the Hutchinson News (Kansas), on November 1, 1922.

“The box supper Friday evening at Red Rock School was a success. There were about twenty boxes and six pies sold. The most popular young lady was Miss Schonholtz, who taught at Red Rock last winter. She was presented with a cake. The homeliest man was Park Coffey. Mr. Coffey’s cake was cut in several slices and sold for 5 cents a slice. The school gave a real nice program. They took in $24.86. The proceeds will go toward buying the necessary things for the school.”

John Vachon caption: Home supervisor with wife of tenant purchase borrower in new kitchen. Labette County, Kansas, November 1940.

(L-R): Dale’s sister Delores, his parents Forrest and Ruth, his wife Beverly, Dale, Pat (Duane’s wife), and Dale’s brother Duane.

Edited interview with Dale Miksch (DM), one of the children in the photograph of the Miksch family. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on November 12, 2012.

JM: When were you born?

DM: 1935.

JM: When did you find out about the photo?

DM: I don’t remember when, but we saw it in the local newspaper.

JM: What did you think of it?

DM: I vaguely recall the picture being taken. At that time, my parents were doing a large remodeling project on the house. They were putting in new cabinets in the kitchen, building a new table for the dining room, and adding a screen porch. I assume that my parents were getting a government loan.

JM: Where did you go to school?

DM: For elementary school, I went to a little brick schoolhouse in Labette. It had three rooms, two of them classrooms, and the other was a large hall with a stage at one end. It was used for indoor recreation and school programs. One classroom had grades one through four, and the other had five through eight.

JM: Where did you go to high school?

DM: We all went to Labette County Community High School in Altamont.

JM: Did you go to college?

DM: I went for one year to Parsons Junior College, which was close to home, and finished my education at Kansas State University. I majored in animal husbandry.

JM: What have you done in your career?

DM: I spent about three years in extension work for the State of Kansas, primarily with 4-H Clubs. After that, and until my retirement, I was in the seed business.

JM: What kind of a farm did you have?

DM: We had 309 acres, but the railroad ran through it. There was another small parcel which I think Dad eventually purchased, and that gave us a total of 320 acres. We grew mostly small grains and corn, and we had cows and pigs. There was a small village about a mile away called Labette. The town where we did all of our grocery shopping was Oswego.

JM: What was it like to have the train going through your property?

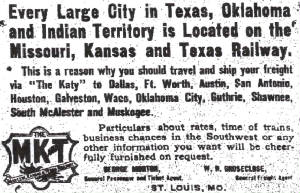

DM: It was kind of fun, but it was also an irritation. Most of the pasture land was on the other side of the tracks, so you had to bring the cattle across the tracks. It was the main line of the Katy Railroad.

JM: There were a lot of hobos on the trains in those days.

DM: I remember quite a few occasions when they would come to the door. Mother would always tell them to wait outside, and she would put food out for them.

JM: Did you have electricity when you were growing up?

DM: We got electricity for the first time in 1947. It was on my 12th birthday.

JM: Did you have indoor plumbing or running water?

DM: No. When that picture was taken, part of the remodeling project was digging a new cistern for catching water. When they were working on it, it was about 10 or 12 feet deep, and I was standing there one time looking over the edge. One of the workers said, ‘Why don’t you jump down here and help us?’ So I did. It was not a smart thing to do.

JM: Did you have to work hard on the farm all through your childhood?

DM: We thought it was awfully hard. It seemed like we were up every morning at four o’clock, milking cows and feeding the hogs. You had to get it all done before you went to school. At one time, we were milking 14 or 16 cows, and sold the milk, and we also sold the cows and hogs. There was a little stockyard by the railroad track in Labette. I remember my father and me taking some cattle to town, putting them on a train, so he could take them to market in Kansas City.

JM: What did you do for fun when you were a kid?

DM: There were a lot of things to do. We talk a lot about what kids do today to have fun, and compare that to what we did for fun when we were kids. Back then, we might have just been pushing a hoop around with a stick or playing in the hay or whatever.

JM: Did you ever have to deal with a tornado?

DM: No. But we had a lot of big thunderstorms. After the remodeling project, we had a basement for the first time.

JM: What were your parents like?

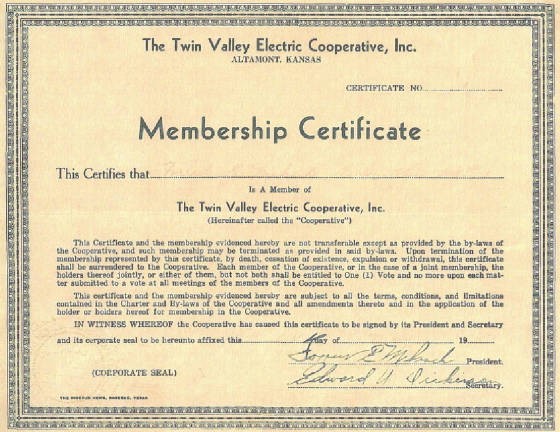

DM: My father was a very conservation-minded and progressive farmer. In the middle to late forties, he spearheaded a movement to bring rural electrification to the area. I remember him making two or three trips to Washington, DC, to lobby for funding. He helped form the Twin Valley Electric Cooperative, and was its president for a while. I admire the way he lived his life, the way he took care of the farm, and the way he went about doing business. My mother was a wonderful cook, a wonderful housekeeper, and a wonderful mother.

Excerpts from interview with Delores Morarity, one of the children in the photograph of the Miksch family. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on January 14, 2013.

“The 1940 photograph has been part of the family for as long as I can remember. I have a framed copy of it hanging in my bedroom. I was only three years old when it was taken.”

“After I graduated from high school, I enrolled in Stormont-Vail School of Nursing in Topeka, and graduated three years later. Then I went to Kansas City (Missouri) and worked for a year at the medical center, and then I moved to Jefferson City (Missouri), where I have lived ever since. One of my classmates and her husband lived in Jefferson City, and she wanted me to visit. I went down on the train from Kansas City, and they sent the director of nurses at the hospital to pick me up at the station. They wanted me to move there and work, and that’s why they arranged it. I ended up getting a job as an obstetric supervisor. I got married in 1966, and I have two children.”

“Dad was not a real affectionate person, but yet, we always felt loved. My mother was sweet and loving. My dad always said she was the best cook in Labette County. Mom and Dad were very close. When we were little, all of the extended family would get together. The adults would play cards, and the kids would play something else. And when we got tired, we’d go pile up on a bed and go to sleep.”

“Dad was a progressive farmer. He terraced the land and took care of it. He had only 309 acres, but he still did well, lived comfortably later in life, and still managed to have money left for inheritance. For never having finished high school, he was quite intelligent and successful. He received the Skelley award (annual W.G. Skelley Agricultural Achievement Award for outstanding farmer of the year). When he finally quit farming, he moved into town, and we were worried about what he was going to do. But he took up woodworking, which he had never done. I’ve got a big sewing cabinet that he made.”

Edited interview with Donald Hellwig (DH), son of Darlene Miksch, the older girl in the John Vachon photo of the family. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on January 24, 2013.

JM: When were you born?

DH: September 19, 1950. I grew up with Grandma and Grandpa Miksch. Mom was injured in a car accident in 1954, when I was just four years old. Dad was killed, and my younger sister and I were both injured. For the most part, my grandparents raised me. I went off to college, worked in various jobs, and when Grandpa chose to retire in 1975, my wife and I returned to take over the farm, and we moved into the old farmhouse that was the subject of the photo.

JM: Did your mother recover from her injuries?

DH: Somewhat. She had a severe head injury, a broken back and hip. She carried some problems from that time, such as balance issues. The trauma surgeons back in 1954 weren’t able to do a lot for her, but she survived, and died about two years ago.

JM: When you lived with your grandparents, did your mother also live there?

DH: Part of the time. She later recovered enough that she could live independently. She attended Parsons Junior College and worked for many years as a private nurse. She lived in Labette, about a mile down the road from the farm, so Grandpa became like my dad. I lived with my grandparents most of the time. By the time I was in grade school, their other children were leaving home. So I was in essence like their only child.

JM: What were your grandparents like?

DH: They were great. They probably had a little more conservative bent than parents of Mom’s generation would have had. But that has stood me well. Grandpa was a good father, and he was also a good confidant in later years. He was rather reserved, but he could become outspoken when the right subject pushed his button. He wasn’t real vocal, I guess until it really mattered. He was a leader in the community. He did a lot of work with various farm organizations. He was the president of the Labette County Farm Bureau at one point. Grandma was very outgoing, but she was not involved in a lot of things outside the home or church. She was very congenial, and a lot of fun to be around.

JM: Were you sort of your grandpa’s right-hand man on the farm?

DH: Yes, I was. I joked that I started driving a tractor when I was four years old, which was a stretch. By the time I was five and six, he would put me in the tractor seat, and I could barely reach the clutch of the old Allis WD with my foot. I was in the field doing things by the time I was in late grade school. I was a member of Future Farmers of America all the way through high school. Grandpa was very much my helper in that, and he got me into my first agricultural project. He helped me get a flock of sheep, which we kept at our farm. He is very much responsible for my love of agriculture.

JM: So when you were growing up, was there any doubt in your mind that you were going to be a farmer?

DH: A little doubt, yes, but I had the desire. Grandma and Grandpa were both very adamant about education. My mom was the only one of their children that didn’t go straight on to furthering their education after high school. And it was assumed that I would do that, too. I enrolled at Kansas State in 1968, and got my bachelor’s in agriculture in 1972. As I was finishing college, Grandpa and I, more than once, fired up the old stove in the shop on cold days and talked about whether there was a way for me to eventually take over the farm.

That was in the early 1970s, and things hadn’t been that rosy for farming in a while, although Grandpa had always made a good living at it. But I wasn’t going to get rich doing it, what with commodity prices going down in the 1960s. He pretty much said, ‘No, no, you don’t want to do this. You can do better.’ So at that point, I didn’t expect there would be much of a chance for me to run or own a farm.

When I got out of college, it was at the end of the Vietnam era, the troops were back home, and it was difficult to get a job coming out of college. I ended up working for a large corporate farming operation in Garden City (Kansas). I didn’t like it much and only stayed there for about eight months. Then a friend helped me get an interview with one of the area farm extension directors, and that led to me getting a job as the Lincoln County extension agent.

I hadn’t been in that job more than six or eight weeks when Grandpa called me, and I remember exactly what he said. ‘Now that you have a good job, do you still want the farm?’ Just like that. And my answer was an immediate yes. I had promised to stay in the job at least two years, so Grandpa and I started planning for my eventual move back to the farm. Two years later, I resigned, and Grandma and Grandpa moved out of the farmhouse and into the city of Oswego, and my wife and I moved into the farmhouse. We had one child at that time, and one on the way. We had a total of four children.

JM: What kind of agreement did you have with your grandfather?

DH: We had a written rental agreement. He had an arrangement with his brother Glenn, who farmed across the road. They were two separate, but adjoined farms, but they shared most of their equipment. They each had their own tractor and plow, but every other piece of machinery was owned jointly. Glenn was three years younger than Grandpa, but they both chose to retire from farming at the same time. That’s what gave me the leverage I needed. When we moved home to take over the farm, we also took over Glenn’s at the same time. I was able to amass enough acreage to get a good start. Each one of them had about half a section (half a section is 320 acres). A local machinery dealer came out and appraised the machinery, and I gave Grandpa and Uncle Glenn each a promissory note for the value of it.

JM: Did your grandfather ever say anything about the Dust Bowl years in the 1930s?

DH: Yes. And he was very much a conservationist because of it. He told me about some of the programs that were attempting to control livestock production. In that part of the state, the dust storms didn’t have as bad an effect. But still, Southeast Kansas, where Grandpa lived, was very much affected by the bad economic times.

JM: When you studied agriculture in college, did you learn some things that your grandfather didn’t agree with?

DH: No, not really. He was a very progressive farmer. From an economic standpoint, I probably wanted to be more aggressive than he was, in terms of expansion. But what he told me about the Depression era probably rubbed off on me. My kids tell me I’m too damn conservative for my own good. But I did expand the farm. My emphasis in college was conservation work, so it was a very good fit for what Grandpa had already done. But I was building terraces with bulldozers, and he built his first terrace with an F-20 tractor and a two-bottom plow. But even with that old equipment, it remains the longest terrace on the farm.

(A terrace is a sloped plane that has been cut into a series of successively receding flat surfaces or platforms, which resemble steps, for the purposes of more effective farming. Terraced fields decrease erosion and surface runoff.)

I don’t remember Grandpa whining about what he had to go through during the Depression. I knew people who lived in that era who were always telling you how bad it was, but Grandpa would just tell me about the things he did to get by, and that was why we were doing the same things now.

The farm is just north of the Oklahoma line, so we were on the northern range of Bermuda grass country. You go much further north, and it can’t stand the cold. He was one of the first to try Bermuda grass as a pasture. I recall that in the mid-fifties, when I was in grade school, Grandpa brought Bermuda grass sprigs from Oklahoma and planted them for the entire pasture. It made for wonderful grazing for many years. He loved cattle. That was the one difference between us. He loved working with animals, and I could stand right next to one that was deathly ill and wouldn’t know it till she took her last breath. He wanted everything to be right for his cattle. He experimented later with fescue, but we still have lot of Bermuda grass that he originally planted.

Another practice that he adopted early on was to abandon the moldboard plow, the one that turns the soil upside down. It was primarily responsible for causing the Dust Bowl. All the sod had been turned upside down, and there was no vegetation left and no crop residue left. We’ve learned from that mistake over the years, and we have better equipment. Grandpa was one of the first to adopt the chisel plow, which doesn’t turn the soil upside down, it just mixes it and lets Mother Nature to do the rest.

JM: When did you finally leave the farm for good?

DH: I like to think that I never really left. But I left the farm as a full-time profession in 1986.

JM: Why?

DH: Economics, the debt crisis of the 1980s being what it was. Grandma and Grandpa lived just a few miles away. I probably spent as much time talking to Grandpa as I did my wife. He was out there every day to help me. I had been his right-hand man when I was growing up, and eventually, it was the other way around.

But at that point, I had another wonderful opportunity; and again, it was connected to Grandpa. One of the things that he did in that progressive era back in the mid-thirties was to pursue electrification. When the Rural Electrification Act of 1936 was signed by Roosevelt, Grandpa very quickly organized the neighborhood to try to get electricity here. They just about had it ready to go when World War II started, and everything went on hold. It started again very quickly after the war ended, and Grandpa, true to form, got the first certificate from the Twin Valley Electric Cooperative. I still have that certificate.

Interview with Donald Hellwig continued

DH: In 1978, I got elected to the Twin Valley Board of Directors. Everybody on that board was closer to Grandpa’s age than mine, so it was, ‘get over in the corner and shut up kid,’ which I never did do. Eight years later, the manager of the Co-op announced her retirement. The debt crisis of the eighties being what it was, I was worried that we were going to become one of those nasty bankruptcies. The going interest rate on loans was 18 percent. I resigned from the board. A couple of months later, the Co-op hired me.

Grandpa was thrilled, and so was I. That gave me the opportunity to stay on the farm and work in town at a professional job. Having expanded over the years, we were farming about 1,000 acres, but because of the job, we scaled it back a lot, and I farmed the place for another 10 years that way. By that time, my own son was growing up. He is also a lover of farming, so he finally took it over in 1996, but he lasted only about two years. Six bushels of soybeans two years in a row took care of that. Ironically, because he had been a farmer, he somehow got a full ride to law school.

He’s a tax attorney now in Wichita, and he told his partners he was going to practice law till he can afford to go back to the farm, so he may someday end up back on the family farm. He’s working on a plan now to make sure that the farm can stay in the family. That way, if my grandsons or granddaughters want to be farmers in a few years, we’ll have a way to get them started.

JM: Who operates the farm now?

DH: We crop share lease it to a young man that lives a couple of miles away. I still go down there every chance I get. In fact, I’m going down there tomorrow. The farm is 240 miles from where I live now, but I’m down there about once every three weeks to build a fence or cut brush.

JM: You’ve known about the Farm Security Administration photo of your family since you were a kid. What does it mean to you?

DH: More now since you called and got me thinking about it. It has always been important because it was one of the few pictures I have of Grandma and Grandpa from that era. Grandpa had many copies of it made, and at one point, every immediate family member had it. He even made frames for all of us. My wife Helen took one of the copies of the picture and had it scanned and put on a quilt, along with other family photos, in honor of my grandparents’ 70th wedding anniversary. In their later years, when they were in a nursing home, that quilt hung on the wall.

My grandparents bought the farm in 1940. They had been living there and operating it for about eight years. They were leasing it from a family that lived in the area. Then they got a $10,000 government loan, which was the reason for the photograph. My understanding is that they paid $8000 for the farm, and $2000 for improvements to the house. Grandpa hand dug a cistern, and laid up the brick and the whole nine yards, and that cistern was large enough to hold 7,000 gallons of water. They did the remodeling, including those cabinets. The door behind Grandpa eventually got moved. And they did a wrap-around porch. Your call has triggered a lot of activity in our family, and we dug out a lot of the old pictures. We’ve had a pleasant trip down memory lane. And your call has made me understand that I need to make sure that my kids get some copies of the picture as well.

Forrest Eldon Miksch: 1906 – 1998

Danzil Ruth Pefley Miksch: 1908 – 2000

Gladys Darlene Miksch Sinclair: 1931 – 2011

Duane Eldon Miksch: Born 1933, lives in Kansas

Charles Dale Miksch: Born 1935, lives in Iowa

Delores Catherine Miksch Morarity: Born 1937, lives in Missouri

The following are excerpts from an article by the late Fred Trump, Public Affairs Specialist with the Soil Conservation Service. It appeared in the Lawrence (Kansas) Journal-World on January 26, 1985, under the headline, “Labette County led way to fight Dust Bowl onslaught.” A newspaper representative told me that he is not aware of any copyright limitations. The article mentions Forrest Miksch, his brother Glenn, and his father Charles.

Kansas farm families and agribusiness people caught in the vise of the cost-price freeze may gain some consolation by looking back 50 years to the Three D’s of 1935 – depression, despair and dust storms. That was the year when Congress took action to do something constructive about the sad state of the environment in the Midwest, and elsewhere in the nation. It was on April 17, 1935, that the Soil Conservation Act went into effect, authorizing creation of the Soil Conservation Service in the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A few farmers in Kansas had already caught the spark of enthusiasm for really doing something about severe soil erosion conditions on their land. But the demonstration projects and the federally employed conservation workers in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) weren’t getting results fast enough.

Farm leaders from around the country suggested a farmer-operated local organization that could be a catalyst for getting conservation practices on the land. So in 1937, President Franklin Roosevelt wrote to the governor of each state suggesting that a state law be passed permitting establishment of local conservation districts. The Kansas Legislature was not the first to respond, but it was one of the first. On April 10, 1937, within six weeks after the president wrote to the governor of Kansas, a conservation district-enabling law went into effect for the Sunflower State.

That was just what a group of farmers in Labette County were looking for. The Extension Service there had already helped develop high interest in terracing and contour farming. By the end of 1937, a total of 2,000 acres of cropland had terraces installed. Soil conservation was off to a running start in Labette County.

Extension agent Maurice Wycoff pushed the idea of applying to form a conservation district. On November 4, 1937, a hearing was held concerning organizing the district. A statement said: “Labette County has made a phenomenal record in building terraces and in contouring in 1937, but additional help is needed.”

At that time, it took 75 percent approval by voters to establish a conservation district. On May 18, 1938, Labette County voters approved establishing a conservation district by an 83 percent margin. The first district board of supervisors consisted of George Rinehart, later a member of the State Conservation Commission; district chairman Arthur Hunter; Claude Payne, who was one of the first farmers to complete his conservation plan: Phil Hellwig; and John Evitts. Other pioneer conservation farmers in the county were Charles Miksch and sons, Forrest and Glenn.

*Story published in 2013.