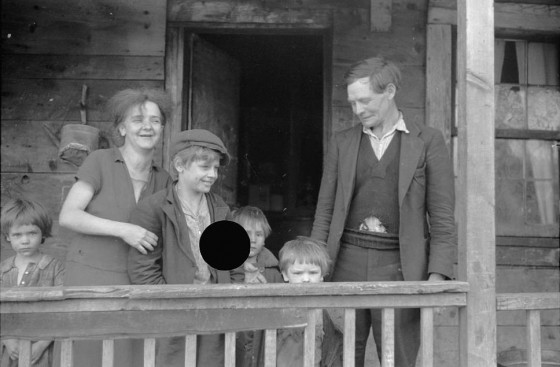

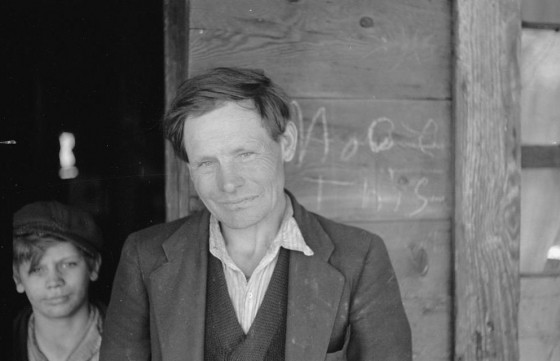

John Vachon caption: The Blizzard family, Kempton, West Virginia, May 1939, John Vachon. (*Note: the photo was taken in Kempton, Maryland, not West Virginia).

“I agree that we were a poor family, but I don’t see how we could’ve been that bad off. We were living on a small farm outside of Kempton then. We didn’t have anybody helping us, but we were getting by with what we had.” -Dorothy Slaubaugh, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Blizzard

“She never used the word ‘poor,’ she just said she didn’t have much, but that her father always seemed to find a way to take care of them.” -Wayne Dillsworth, son of Nellie Blizzard

“One time when we visited, Grandpa (Blizzard) was going to the store, and he asked me if I liked bananas. I told him I did, and he came back with a huge basket of them.” -Marjean Cool, daughter of Mildred Blizzard

“He didn’t get any further than the sixth grade. When he was young, he worked on a farm for about 25 cents a day, just so he could help his parents. He started working in the coal mines when he was 18.” -William Blizzard, son of Carl Blizzard

“I think it’s great to be able to see my dad and his brothers and sisters, and what things were like when they were young, you know, not having a thing, and to see where they ended up. They didn’t have much as kids, but the family was there and the love was there.” -David Blizzard, son of George Blizzard Jr.

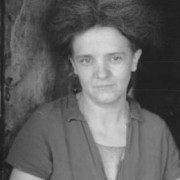

This is one of my favorite photographs by John Vachon. He portrays the family with great dignity and respect, as he did in all of his pictures for the Farm Security Administration. The parents and their children seem at ease and comfortable with who they are. Mr. Blizzard leans slightly toward the camera. Mrs. Blizzard, with delightfully unruly hair, smiles warmly. The children, who strongly resemble their mother, are beautiful, and the parents look genuinely proud of them. One glance, and I care about them, and I want to know more.

Before I tell the story of this family, let’s look at the photographer, the mine, and the town of Kempton.

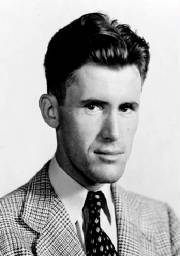

John Vachon

The following is from a 1964 interview of John Vachon, the photographer of the above picture. The interview was conducted by Richard Doud, for the Smithsonian Institute.

Doud: Do you remember – I’m sure you do – your first major assignment as a photographer, and how you went about getting ready for it, what you did to prepare yourself for it?

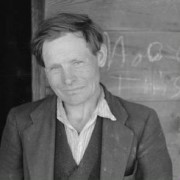

Vachon: One which only lasted about three days, maybe less, two days, I think, and I don’t remember what led up to it, but it was just one in which I happened to get some pictures which I have always liked quite a bit. It was to go to a coal town in West Virginia (Maryland) called Kempton, which had been where the mine had (temporarily) closed. You know, it was one of those poverty stories, and I went with a guy named Harold Bellew (Ballou), who was an information adviser or something. I can’t recall what connection – you know, how this fit in with Farm Security or Resettlement, what they were considering doing for these people, but we spent two or three days in that town, photographing families, and housing, and children. I can’t recall any preparation, except that I think that I was probably, more than any other photographer who ever worked there (for the FSA), imitative, because I had been so exposed to all these other photographers, and particularly Walker Evans, who had a great influence on me. I went around looking for Walker Evans’ pictures.

************************

John Vachon was about to celebrate his 25th birthday when he was dispatched to Kempton in May of 1939. He had been using a camera for only a short while when he was hired in 1938 as a photographer for the Farm Security Administration. He took 128 photographs in Kempton, 20 of the Blizzard family, some untitled and/or unpublished. His simple, straightforward and moving portraits of life in this remote mining village should be regarded as some of the finest work he produced in his illustrious career.

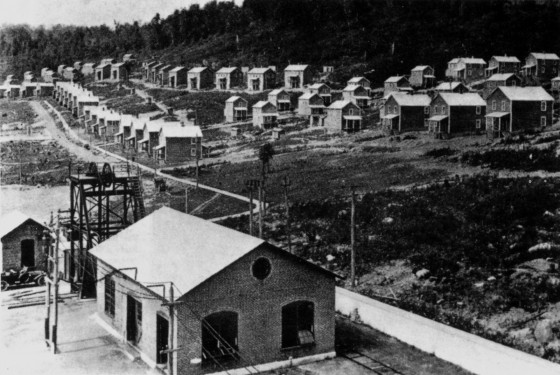

Davis Coal and Coke Company, Kempton, Maryland

“Seventy-one miners were caught by an explosion at the Kempton mine of the Davis Coal and Coke company, on a spur of the Western Maryland railway, about two miles from Fairfax, W. Va. Twelve dead bodies have been recovered, five after several hours’ search. It was expected that one more body will be found, bringing the fatalities to thirteen. All but three or four men known to have been in the mine are now accounted for.”

“The mine was not badly wrecked, according to mine officials. The explosion, it was stated, was probably caused by dust. The men had scarcely reached their working places when (because) of the blast, hurried to the location it occurred. Those not directly in range of the blast hurried to the main entries and started for the foot of the shaft in which the cages were still operating. There they were met by rescue parties from the surface and quickly hoisted. Other rescuers made their way into the mine and soon located several bodies. Later other miners who had been unable to reach the main lines of communication were found and brought out.”

“The mine is in Garrett County, Md., and is practically new, with all modern machinery. It is a shaft mine, 430 feet deep with seven or eight miles of headings. The machinery of the mine was not damaged and the cages working expedited the rescue of the imprisoned men. The explosion occurred about 2000 feet from the shaft bottom. Falls of coal from the explosion delayed the rescue work. The mine is devoid of gas. The identification of the men taken out has not yet been established. Several are burned and badly maimed. The mine has a capacity of about 2000 tons a day.” –Tyrone Herald (Pennsylvania), March 2, 1916

“Have you heard the news from Kempton? Splendid isn’t it? Something to be proud of. Kempton, the youngest town of Garrett County; Kempton, a mining town on the Western Maryland Railroad; Kempton, one of the patriotic towns of the county, the town that does things.” -Oakland (Maryland) Mountain Democrat, July 4, 1918

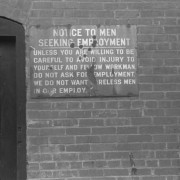

Sign on road to Kempton, West Virginia-Maryland. The post office and company store are in West Virginia. Miners pay the West Virginia sales tax. The rest of the town is in Garrett County, Maryland, May 1939, John Vachon.

According to Where the Potomac Begins, by Gilbert Gude (1984, Seven Locks Press), the Davis Coal and Coke Company in Kempton, Maryland, began operations in 1914. It was situated about one-and-a-half miles downstream from the Fairfax Stone, where the first trickle of the great Potomac River begins. Kempton straddled the border of Maryland and West Virginia. The mine and the surrounding village of Kempton were located in Maryland, but the post office and company-owned store were on the West Virginia side. (Vachon incorrectly specified the location of his photographs as West Virginia). I have either changed that to Maryland, or left out the state name in the few cases where I have quoted his captions).

The company built the mine and houses on a hillside above the Potomac, where a strip of ground was cleared three quarters of mile long and several 100 feet wide. Most of the residents lived in single-family houses, with four to six rooms, an outdoor toilet, and a small lot, enough for a lawn in front and a small garden in back. Next to the company store was an arcade called the Opera House, with a lunchroom, bowling alleys, pool tables, dancing floor and auditorium. The streets were unpaved. By 1918, Kempton had 106 houses and a population of 850.

(Left): Sign at entrance to mine, Kempton, May 1939, John Vachon.

(Right): Sign in English, German, Hungarian, Italian, Lithuanian, Czech, and Polish, Kempton, May 1939, John Vachon.

The workers started their first union not affiliated with the company in the early 1930s, and after that, it was common for them to institute a 30-day strike before the annual contract was renewed. Such a strike was occurring when Vachon visited the community. Ironically, about one month before he arrived, the Davis Coal and Coke Company had shut down its operations in Boswell, Pennsylvania, only 90 miles north of Kempton.

**************************

“Boswell, Somerset County mining community, founded shortly after the turn of the century, faced a bleak future today. Officials of the Davis Coal and Coke Company disclosed that their large operation is in the process of abandonment. Boswell is 10 miles north of Somerset. Closing down the mine will throw 170 persons out of jobs, and leave the community of 2,000 inhabitants without an industry of any kind.” –The Charleroi Mail (Pennsylvania), March 31, 1939

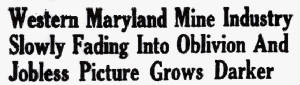

Only 11 years later, the company closed its operations in Kempton.

“Western Maryland’s mine industry is slowly being squeezed out of operation, coal men familiar with the area fear. Spokesmen said that underscoring the continuing trend to lower production and greater miners’ unemployment was the closing of Maryland’s largest mine. The Davis Coal and Coke Company shut down its No. 42 mine at Kempton, Garrett County, Saturday. The 1,200-ton-a-day operation was mechanized and employed about 250 diggers. Equipment is being dismantled now and shipped away. Garrett County Commissioners confronted with a bad jobless situation, promptly moved to have the county declared a federal disaster area. Kempton’s only store, which employed seven people, also closed Saturday.”

“Coal men believe the mine slump is far more than just a seasonal depression due to present market conditions. They attribute it to a competitive disadvantage of Western Maryland coal, a low volatile grade, and they see no prospect for sufficient demand to make it profitable again. Production costs at Kempton, a Davis spokesman explained, were ‘way out of line’ with the type of coal produced.” –The Daily Mail, Hagerstown, Maryland, April 21, 1950.

The Blizzard family

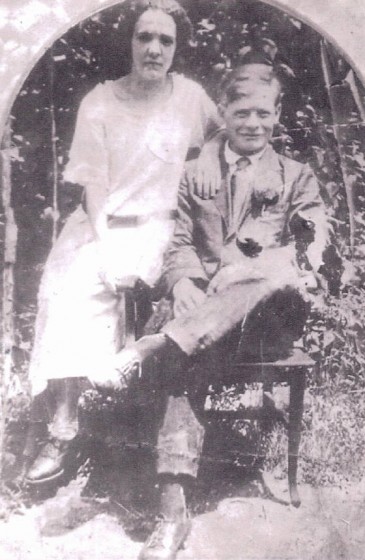

George David Blizzard was born in Grant County, West Virginia, on September 7, 1887. He married Nanna Bowser, probably about 1910. They had one child, Daisy, who was born in 1911. The marriage ended in divorce. On May 2, 1926, he married Lillie V. Sims, in Mineral County, West Virginia. He was 38 and she was 22. She was a native of Preston County, West Virginia.

They had nine children, one of whom, Edward, died in 1930 at the age of six months. According to one family member, they had several others that were stillborn or lived only a few days. In the 1930 census, the family was listed as living in Garrett County, Maryland, in an area called Ryan’s Glade, about 15 miles north of Kempton. George was working in an unspecified coal mine. They moved to a farm in the Kempton area shortly after. When the family was photographed in 1939, they were living on a farm near Kempton, not in the mine village.

In the 1940 census, the family was listed as living in the mine village of Kempton, Maryland, at 31A Toney Street. All of the eight children living with them were attending school, except for the youngest three, which were all under the age of six. The census noted that George left school after the third grade, and wife Lillie left school after the sixth grade.

Lillie died on November 27, 1960, at the age of 57. George died three years later, on December 17, 1964, at the age of 77. He was survived by eight children, 36 grandchildren, and 10 great-grandchildren. Both were living in Gormania, West Virginia, about 15 miles from Kempton.

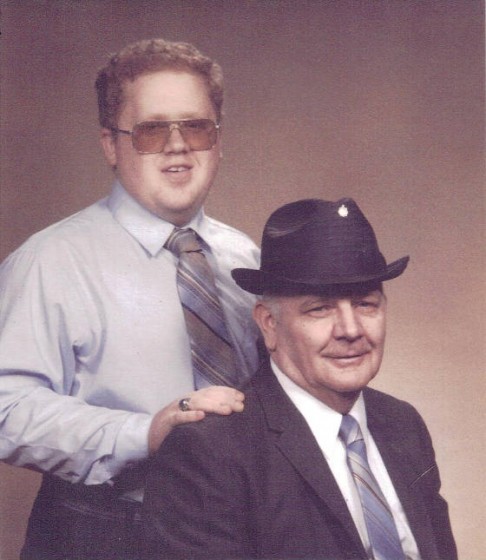

Lillie and George Blizzard with (L-R): Mildred, Carl, Nellie and Dorothy. This is an unpublished photograph by John Vachon, which explains the large black spot near the center.

After obtaining several obituaries of the Blizzard children, I contacted and interviewed Dorothy Slaubaugh, the only surviving child shown in the photographs. I also interviewed a son or daughter of Carl, Mildred, Nellie and George Jr., the four other children shown in the photographs. One other child is still living, Mary, but for health reasons, she was unavailable for an interview. She did not appear in any of the photographs.

Carl Blizzard

Carl Martin Blizzard was born on January 21, 1929. He married Ruby Jordan. They had two children. Carl served in the Korean War, worked for many years for the Island Creek Coal Company, and was also an auctioneer. He died in Maryland on August 8, 2002, at the age of 73. Ruby died in 2011. Survivors included two children, four grandchildren, five great-grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Edited interview with William Blizzard (WB), son Carl Blizzard. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on August 17, 2013.

JM: Did you know about these photos of your family?

WB: Yes, I saw them in the book, Where the Potomac Begins. My father didn’t like the pictures. He didn’t want people to see how he lived when he was growing up. I bought a copy for him, but he shoved it into a bookcase in a place where you couldn’t see it. But I don’t have a problem with the pictures. A lot of people had to grow up like that back then.

JM: Did he tell you much about his life as a child?

WB: He didn’t get any further than the sixth grade. When he was young, he worked on a farm for about 25 cents a day, just so he could help his parents. He started working in the coal mines when he was 18. He talked a lot about helping his dad at the mine. He said his father had to work really hard to keep his family fed. His mother used to cook supper on a coal stove. He told me about the death of his little brother Edward, who died when he was just a baby; and about his sister Agnes, who died at the age of 18, while he was stationed in Korea.

WB: I found his Army papers, and the VA sent me all of his medals. One of his sisters told me that when he got home from Korea, he burned his uniform. He must have had some bad memories of the war. He worked 39 years in the mines at the Island Creek Coal Company in Bayard, West Virginia. We didn’t live in Bayard, we lived in Terra Alta, which is about 38 miles from Bayard. So he drove to work every day. He also worked as an auctioneer. He started doing that in 1966, but he continued to work at the mine. He liked to tinker around at home. After he retired from the mines, he built sheds and other outbuildings and sold them.

JM: How many children did your parents have?

WB: Two. He adopted me when I was six months old. My mother had a child from a previous marriage.

JM: Did you graduate from high school?

WB: Yes, but I didn’t go to college. I helped him for a while with the auctions. Later, I worked for Wal-Mart for 18 years. I worked in the pharmacy for part of the time.

JM: Was he in good health most of his life?

WB: He told me he had rheumatoid arthritis as a kid, but I guess he got over that. He got hurt in the mines a few times. He had several heart attacks. The last one, in 2002, was massive and it took him. My mother died two years ago.

My first child was born with a club foot. My dad said that before he died, he wanted to see her walk. He did, just a couple of minutes before he passed. She was in the room, and he said to her, ‘Come over here,’ and she pulled herself up from the floor and walked over and got in his lap, and then she got back down. And then he said, ‘I’m going,’ and he died.

Mildred Blizzard

Mildred Delores Blizzard was born on April 8, 1933. She married Earl Lipscomb. They had six children. They lived in Barberton, Ohio, most of their lives. Earl died in 1998. Mildred died in Barberton, on December 31, 2002, at the age of 69. Survivors included six children, 12 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Edited interview with Marjean Cool (MC), daughter of Mildred Blizzard. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on August 30, 2013.

JM: When did you see the photographs the first time?

MC: My sister-in-law told me that they were online. I hadn’t seen them in the book yet (Where the Potomac Begins). When that book came out, my mother was very upset about them, and so she didn’t buy the book. She said, ‘They made my daddy look like he was a bum.’ If you knew my mom, and the way she felt about her dad, anything that might make him look bad would really offend her.

JM: What did you think about them?

MC: I knew my grandfather had worked in the coal mines. And if you live in a coal mine town, and you go outside, you’re going to get really dirty. My grandmother and grandfather looked to be okay with the way they and the kids looked. After all, they were letting the photographer take the pictures, so I don’t think they thought there was anything wrong with it.

JM: I thought they looked comfortable with who they were. Your grandmother’s hair was sticking up, but she was smiling and didn’t seem the least bit self-conscious.

MC: When I saw Grandma with her hair like that, at first I wondered why she didn’t comb her hair for the pictures. But her sisters all had a problem with their hair if the humidity was high. It would get frizzy. My mother had the same problem, and so do I, but we had gel to keep it down.

JM: What year were you born?

MC: 1956.

JM: At that time, where were your parents living?

MC: In Barberton, Ohio.

JM: Did they own their house?

MC: Not at that time. We lived in a project. During that time, Dad was working off and on at B & W (Babcock & Wilcox). There were times when they would lay off people. My parents still owned a house in Kingwood, West Virginia, so Dad would go back there to work when he got laid off.

JM: What was it like growing up in Barberton?

MC: It was a very small town, right next to Akron. I was the only girl. My three older brothers went to public school. When we moved from the projects to the house that my parents bought, there was a Catholic school right across the street. Walking to the public school from there was a little over a mile. That was fine for the boys, but Dad wanted me right across the street where it was convenient, even though we were not Catholic. After that, my two younger brothers also went to the Catholic school. When we got to the eighth grade, we all went to the public school.

JM: Did your mother work when you were growing up?

MC: No, except for some cleaning of houses that she did for a while. She had six kids to raise and take care of.

JM: Did she graduate from high school?

MC: I think she went as far as the eighth grade.

JM: Did your mother tell you what her life was like when she was growing up?

MC: When she was a girl, her mother made her go into the kitchen and learn to make bread. She cried all the way through it because she thought she should be outside helping her dad in the yard. She was very close to her daddy. But she went ahead and learned, and when she made her first loaf of bread, her mother told her, ‘That was the best bread ever because your tears are in it.’ I remember my mom canning and all of that, so she learned to do what her mother taught her.

She talked about how her dad, every Saturday, would give the children enough money so they could go to the movies. I remember her talking about all of the babies that died. The only two she mentioned that had names were Minnie and Kenneth. Grandpa would bury them. She said that her parents had a total of 14 children, but only eight survived to adulthood. She talked a lot about her sister Agnes, who died when she was about 18. They were very close.

JM: Do you remember your grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. Blizzard?

MC: I was only four years old when Grandma died, and only eight when Grandpa died. We lived in Ohio, and they lived in Maryland. We would go there in the summer to visit. I remember that Grandma’s gray hair was so pretty. One time when we visited, Grandpa was going to the store, and he asked me if I liked bananas. I told him I did, and he came back with a huge basket of them. I remember Mom talking about one time when Grandpa had sent money to her. She knew he didn’t have much money. But he wanted Mom to buy something for all of us kids. So she used just part of it and sent back the rest.

My mother was very giving. Her little church was about 10 or 15 people. For Christmas, she would want to buy something little for everyone in the church. She dearly loved her grandchildren. They were her life, and she would do anything for them. When I had my first grandchild, she was on cloud nine.

JM: Was your mother in good health most of her life?

MC: In her later years, she got diabetes, and she had congestive heart failure. She died on New Year’s Eve of 2002. My father was 13 years older than my mother, and he died in 1998.

My mother loved gladiolas, so I planted some in the spring and took them to her grave. I miss my mom very much. There was never a time we would talk or visit that we didn’t tell each other, ‘I love you.’ She was that way with all her family.

Nellie Blizzard

Nellie Mae Blizzard was born on August 11, 1934. She married Edward Dillsworth. They had two children. She died in Oakland, Maryland, on July 16, 2011, at the age of 76. Survivors included her husband and their two children.

Edited interview with Wayne Dillsworth (WD), son of Nellie Blizzard. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 31, 2013.

JM: What did you think the first time you saw the photographs of your mother as a little girl?

WD: I thought it was kind of cool. I saw them in the book, Where the Potomac Begins.

JM: Did the pictures confirm what you already knew about her life as a child?

WD: Sure. I heard those stories for years. She never used the word ‘poor,’ she just said she didn’t have much, but that her father always seemed to find a way to take care of them. She said she was just like Loretta Lynn in Coal Miner’s Daughter.

JM: Do you think she struggled as much as one might imagine from seeing the pictures?

WD: I think they would have been a little better off than people would think. I know that some of her siblings were very angry about the pictures in the book. One of her sisters consulted a lawyer about suing the author to get the pictures out of the book. But they didn’t bother my mother at all. She actually had a copy of it autographed by the author.

JM: When did your parents get married?

WD: January 19, 1957.

JM: How many children did they have?

WD: Just me and my sister, who was born 10 years after I was.

JM: When were you born?

WD: 1962.

JM: Where were your parents living at that time?

WD: In Oakland (Maryland). When I was two or three years old, they lived about half a mile from where I live now. They rented the house.

JM: Did they ever own a house?

WD: Yes. The last house they owned was built by my father, and he still has it.

JM: Did your mother work outside the home?

WD: No, not after she had me.

JM: Did your mother graduate from high school?

WD: No.

JM: What did your father do for a living?

WD: He worked in the logging business. He retired from that about five years ago, and he drives a tractor-trailer now. He never stops working.

JM: What was your mother like?

WD: She was a good mother. She was a lot of fun sometimes, but if you did something wrong, she’d straighten you out. She was kind of a homebody. She liked picnics and family reunions, and that kind of stuff.

JM: What about your father?

WD: When I was growing up, if he wasn’t working, he was in bed. He believed in working all the time. He still does. Unfortunately, I’m just the opposite. I believe in putting things off till tomorrow.

Dorothy Blizzard

Edited interview with Dorothy Blizzard Slaubaugh (DS), daughter of George and Lillie Blizzard. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on February 25, 2013.

JM: You told me that you saw some of the pictures a few years ago.

DS: Yes. I first saw them in a book (Where the Potomac Begins). My oldest sister was very upset with them. There was one picture that I did not like. The kids were putting on these old coats and stuff. One had put on shoes that didn’t match. They were just playing. They wouldn’t have dressed like that normally. I agree that we were a poor family, but I don’t see how we could’ve been that bad off. We were living on a small farm outside of Kempton then. We didn’t have anybody helping us, but we were getting by with what we had. During the Depression, we got coupons to buy shoes, and to get sugar and things like that. My mother canned a lot of stuff. We butchered a lot of our meat and canned that, too.

JM: When were you born?

DS: January 1, 1936. When I was about four years old, we left the farm and moved into the coal mining town. There were some pretty good houses there, though they were old, and they all looked alike. I walked to school. Later, we went to school in Thomas, West Virginia, so we had to walk to the post office across the state line to get the bus, because we couldn’t take a bus from Maryland. We had a car, but someone else had to drive us, because neither of my parents could drive.

We lived there till I was about 13. Then we moved over to Gorman, Maryland, in what they called Table Rock. We bought a house there, a nice big house. We had an outdoor bathroom, and we had to carry our water from the spring, because we had no running water. We owned two horses, some pigs, and cows and chickens. Our main meat was served on Sunday. We never felt poor, but I felt like we didn’t have as much as some of the other people.

But we lost the house, because my father was on strike and couldn’t keep up with payments. He was getting some money from the union, but it wasn’t enough. A friend of ours owned a vacant house back off the road, which was a nice house, so we rented it for a while. That was in Gormania, West Virginia. My dad was still on strike. I don’t think he ever worked again in the mines after that. After he retired, he got a pension.

DS: I lived in Gormania until I grew up and got married to John Slaubaugh in 1953. He and I moved to Barberton, Ohio. That’s where most of the work was. I had a sister, Mildred, living there, and she told us they were hiring at Babcock and Wilcox, a big construction company. We lived there about two years. And then they started laying people off, so my husband had to find another job. We moved to Arlington, Virginia, where he got a construction job. He built houses and things like that. We had a total of 14 children.

JM: Did you or any of your siblings go to college?

DS: No.

JM: How many graduated from high school?

DS: My oldest sister Mary did, but I think she was the only one.

JM: Your father died in 1964.

DS: He had that disease in the lungs that miners get (pneumoconiosis, commonly called ‘black lung disease’), but we never could prove it, because when he was very young, he accidently shot himself while he was hunting, and they could’ve blamed it on that. He died of a heart attack while he was being treated in the hospital. My mother had died four years before. She was only 58. My father was married before. My mother was in her twenties when they got married. My dad had a 15-year-old daughter from his first wife.

My mother was a hard worker. She helped a lot on the farm. She was very pleasant to be around. My father was a very nice man. He was very understanding. We used to have a lot of fun together. My older sister Mary and I are the only children still living.

Lillie Blizzard, with (L-R): Nellie, Carl, Dorothy, Mildred, May 1939. Photo by John Vachon.

The following are excerpts from my interview with Janine Shirley, one of Dorothy Blizzard’s 14 children. She was born in 1961, in Arlington, Virginia.

“My mother had a lot of faith in God. When we were growing up, we would all get together every evening, and she would read to us from the Bible. And then we would say a prayer and go to bed.”

“She said that her parents made sure all of their children went to school, even if they had to walk in a snowstorm. My mother also believes strongly in education. All of us had to go to school, and had to do our lessons. She would help us with our schoolwork. She would answer any questions we had to the best of her ability. She was very intelligent. She didn’t finish high school, but she went back and got her GED.”

“She knew math very well. And she continued to learn as she helped each of us with our schoolwork. When all of us grew up, she loved children so much that she became a teacher’s aide in the schools. At least two of us children went to college.”

“My parents have always been very close. They do everything together. Our whole family has always been very close. When I was growing up, practically every Sunday after church, we would go out to McDonald’s, and then to the park, where we played baseball. My mother loved to play and run the bases. She also loved to play Jacks and horseshoes.”

“I asked her once why she had so many children, and she told me it was because she never wanted to be alone. And now we children are grown and have our own families, most of us live in the same area, and we often have family reunions and get-togethers.”

“In those pictures the government took, I could see how much my mother and her siblings had to struggle to get by. But I believe that kind of a struggle can make you stronger as a person. You learn that the most important things in life are God, family, a place to live and enough to eat. My mother always says, ‘It doesn’t matter where you live, it’s what you make of your home.’”

“My mother is humble, just like her parents were. She doesn’t really understand how much of a positive effect she has had on us children. She has always been a strong, vibrant woman, with a lot of pride and a lot of faith. She continues to be loving, caring and nurturing. She has the warmest hands. I can remember when I was growing up and had an ear infection, she would cup my ear in her hand, and it would sooth the pain.”

George Blizzard Jr.

George David Blizzard Jr. was born on February 5, 1937. He married Helen Dillsworth, sister of Nellie Blizzard’s husband Edward. They had six children. He worked in construction most of his life. George died in Virginia on September 17, 2010, at the age of 73. Helen died a year later. Survivors included seven children, 21 grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

Edited interview with David Blizzard (DB), son of George Blizzard Jr. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on August 20, 2013.

JM: When were you born?

DB: 1960.

JM: Where were your parents living then?

DB: With Grandma and Grandpa Blizzard, at the old home on Table Rock (in Garrett County, Maryland). When I was two years old, we moved to northern Virginia.

JM: Why?

DB: There was no work in Garrett County, except for the coal mines and logging. My father got a job in construction. He did a lot of concrete work and a lot of bridge work at first. He had dropped out of school in the sixth or seventh grade. But despite that, he was a heck of an architect. I remember when I was a kid, he would bring home a set of plans, roll them out on the table, and by the next morning, he would have it in his head how he was going to build whatever it was he was working on. Most of the work he did was for companies, but once in a while on weekends, Dad and his brother-in-law Johnny would go out and get work to build houses, from the ground up. In his later years, he did a lot of asphalt work. A lot of it was put down by hand. I worked with him for a while when I was young. The company had an old flatbed, and we could haul about 10 tons at a time. I remember sometimes we’d work from early morning till 3:00 in the afternoon, and by that time, we had put 100 tons of asphalt down by hand. And then he would tell me to go get another load.

JM: Did he build the house you grew up in?

DB: No. Dad rented, but when he got older, he bought a couple of houses.

JM: How did your parents meet?

DB: Mom’s older brother married one of Dad’s older sisters (Nellie), and that’s how they met.

JM: When were they married?

DB: March 4, 1959. I remember that, because my wife and I got married on March 4, 1979. We planned it that way, and my parents were very pleased.

JM: How many children did your parents have?

DB: Six. I am the oldest.

JM: Did your mother ever work out of the home?

DB: No.

JM: Did your father see the famous photos of your family?

DB: I don’t know. But if he could see them today, I know he would be tickled to death.

JM: What do you think of them?

DB: I think it’s great to be able to see my dad and his brothers and sisters, and what things were like when they were young, you know, not having a thing, and to see where they ended up. They didn’t have much as kids, but the family was there and the love was there.

JM: Did you graduate from high school?

DB: I quit in the 10th grade. For the past 11 years, I’ve been managing a compost operation for Spotsylvania County. We take human waste from the wastewater treatment plant, mix it with mulch, and make the compost. It’s great for landscapers and gardeners. A few years ago, they changed the qualifications and wanted everyone to have a high school diploma or GED. So I went back in 2008 and got my diploma.

JM: How many children do you have?

DB: Two.

JM: Did your father tell you much about his childhood?

DB: He talked about how they didn’t receive much on Christmas. He could remember his father coming home with fruit baskets. He never complained about it. That’s one of the reasons my parents moved to Virginia, so we kids wouldn’t have to grow up the way he did.

JM: What was your father like?

DB: My Aunt Dorothy told you that her father – my Grandfather Blizzard – was a very nice person to be around, and that he was very understanding. My father was like that. He would take me fishing when I was a kid, but I remember that he didn’t have much patience waiting for the fish to bite. I’m the same way. Picnics were the big thing. Many times, on the spur of the moment, he would say, ‘Let’s go get some KFC (Kentucky Fried Chicken) and have a picnic.’

JM: Given that he grew up poor, was he frugal with his money?

DB: He knew how to pinch a dollar. He knew how to save and not buy things he didn’t really need.

JM: Are you like that?

DB: No, but I grew up in a different world. But I picked up a lot of his work habits. He was never late for work. I’m the same way. My wife is always asking me, ‘How come you’re going to work so early?’

JM: Was your father in good health before he died?

DB: Up to the last couple of years, and then he got a collapsed lung. He never smoked, so it was probably caused by the type of work he did. When you work in construction, especially when you’re handling concrete, you’re always breathing in some kind of dust.

JM: Your Grandfather Blizzard died when you were four years old. Do you remember him at all?

DB: A little. I remember getting out of the car when we would go visit him, and he would be standing on the front porch. He always had a pack of Teaberry gum in his pocket, and he made sure I got a stick of it. He passed away in the hospital in 1964. They were about to release him, and my dad went to pick him up and bring him to our house. Mom was cooking a big dinner to celebrate. Dad had him up and was putting on his shirt, and he suddenly died of a heart attack.

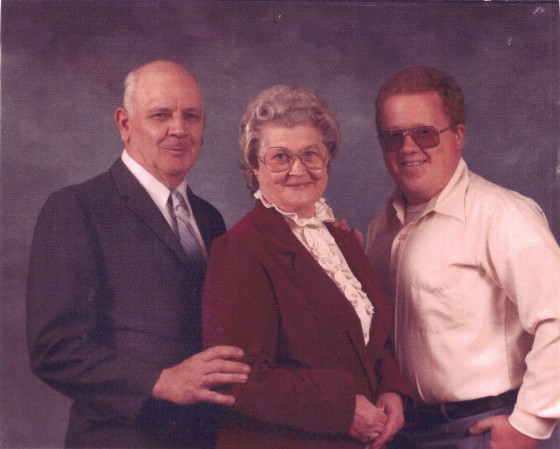

George Blizzard Jr. and wife Helen, with five of their six children (L-R): Sara, Brenda, David (interviewed above), Cindy and Helen.

Children of the Blizzard family in the photographs

Carl Blizzard: 1929 – 2002

Mildred Blizzard: 1933 – 2002

Nellie Blizzard: 1934 – 2011

Dorothy Blizzard: 1936 –

George Blizzard Jr.: 1937 – 2010

The other children in the Blizzard family

Daisy Blizzard: 1911 – 2002

Survivors included: four children, 26 grandchildren, 39 great-grandchildren and seven great-great-children.

Mary Blizzard: 1926 –

Betty Blizzard: 1927 – 2012

Survivors included: nine children, 31 grandchildren and 63 great-grandchildren.

Edward Blizzard: 1930 – 1930

Agnes Blizzard: 1931 – 1949

In May of 1939, John Vachon captured this beautiful image of a coal miner looking down at the town where he lives and works. Eleven years later, the mine would close for good. It’s been 74 years since Vachon left Kempton with his camera. It is no longer an official town, just a geographical location with only a handful of families living there.

*Story published in 2013.

See what Kempton looks like now in pictorial essay about the town