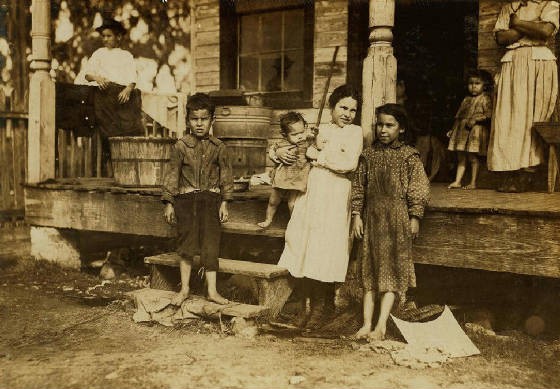

Lewis Hine caption: Alma Crosien, three-year-old daughter of Mrs. Cora Croslen, of Baltimore. Both work in the Barataria Canning Company. The mother said, “I’m learnin’ her the trade.” Location: Biloxi, Mississippi, February 1911.

“It was hard times back then. That house they were living in looks like a rundown shack. I’d seen some of those shacks down in Biloxi when I was a kid. You could see through the walls when you went in them.” -Joseph Olier, son of Alma Alves

On August 25, 2009, I saw this photo on Shorpy.com, a popular photo blog that posts historic photos, often those of Lewis Hine. After several frustrating hours of searching almost frantically, the only thing I could find was Cora Croslen and her husband in Biloxi in the 1910 census, but childless. I posted this as a comment on Shorpy.com. Two days later, I received an email from a Shorpy reader.

“I looked at the 1910 census record for the Croslens and saw that a neighbor, age 3, was named Alma. Her mother was also an oyster opener. The parents were given as Peter and Angelina Alvells. In the 1920 census, Peter and Angelina Alves, with Alma, are still there. In 1930, Peter is gone but Alma Olier and her husband live with Angelina Alves. Alma and Angelina work for a seafood company. Hope this helps in your search.”

Within a few minutes, I had found an Alma Alves Olier in the Social Security Death Index. She died in Biloxi in 1987. Then I found some of the Alves family history on OceanSpringsArchives.net, a terrific site created by historian Ray L. Bellande. Before the day was over, I had tracked down Alma’s youngest son and talked to his wife for a few minutes.

After I hung up, I went to my computer to print a copy of the photo, so I could mail it out to them. When I did, I accidentally found another photo of Alma, this time with some of her brothers and sisters, identified as the Peter Elvis (obviously Alves) family. From the moment I had seen the first photo, I wondered why Cora and Alma didn’t look the slightest bit alike. Now I knew. Cora was probably babysitting while Alma’s parents were working. Both photos went out in the mail. The next day, I found a photo of Alma’s brother Joe.

Lewis Hine caption: Family of Peter Elvis, New Orleans, La. All except smallest baby work in the Barataria Canning Company. Youngest boy, Jo., seven years old works Saturdays. Alma, the three year-old by the door is “learnin’ the trade” her mother said. Location: Biloxi, Mississippi, February 1911.

Lewis Hine caption: Howard Simmons and Joe Elvis, two of the smallest here, both shuck oysters in Barataria Canning Co. Location: Biloxi, Mississippi, February 1911.

Edited from North & South: Devoted to Health, Happiness and Honesty, published in 1904.

Whatever may be written of the Gulf Coast region – its fruits and flowers, its vegetables and nuts – is incomplete without a mention of its great oyster beds. They supply two-thirds of the world’s demand for oysters, are perhaps more responsible than any other one thing – climate not excepted – for the lack of agricultural development on the part of the natives. With a small boat and a pair of oyster tongs no one in the region of the Mississippi Coast need fear starvation. It is this luscious bivalve primarily to which much of this condition must be hid – for it furnishes not only ready food but ready money at notice, inasmuch is everyone eats oysters on this coast, summer and winter alike, and the leisure classes prefer buying their supplies to manipulating the oyster long on their own account.

Scattered along the coast between Mobile and New Orleans are many great oyster canning factories, where from September until May, the business of pulling up the giant product is carried on. Biloxi has the largest factory in the world, and quite a group of the canners are congregated here so that the name of this city is synonymous with that of the oyster.

The oyster beds skirt the Mississippi and Louisiana coast and are hundreds of miles in area, thus being utilized by the canneries of both states and producing a heavy revenue for each. Between 300 and 400 schooners and small barges haunt the oyster grounds daily during the season, and flights of these little ships constantly wing their way to and from the beds.

At the oyster wharves an interesting scene is enacted when the ships come in and null up alongside the little “oyster railroads” with their miniature trains of cars. With automatic hoists the oysters are lifted to the wharf and emptied into the cars. When filled, each train runs into the factory where a picturesque line of Bohemians, men, women and children, awaits them and falls to opening the shells as soon as they are steamed. The dexterity with which they learn to extract the bivalve is fascinating. As their tin cups are filled, they are paid in cash. Shuckers make from 60 cents to $1.25 per day and besides this wage, receive free houses, fuel and water from their employers.

Labor is an ever-present problem with the oyster canners – most of it comes from Baltimore, but the briefness of the season and lack of all-year-round employment deters many from making the long journey to the coast. In order to obviate this condition, the canners have tried canning various products – cane syrup, figs, vegetables – but none has been sufficiently successful up to date.

All along the coast the big canning factories loom up alongside mountains of bleached oyster shells. It is little wonder that the roads in this region are so fine. The shell of the oyster ground into dust makes a highway as hard as asphalt, dazzlingly white in the Southern sun and stretching away beneath the pines.

The five canning factories at Biloxi which is the most centralized point in this great industry, employ 2,000 to 3,000 men, women and children for eight months in the year, putting up sea products, fruits and vegetables. The raw oyster shipping industry is a business in itself, employing 200 to 300 men from September to May, who earn from $2.00 to $3.00 a day.

Lopez & Dukate, at Biloxi, have the largest of the coast canneries; in fact, the largest in the world. The city of Biloxi owes its growth and progress largely to this firm. Its public buildings, new street railway system, as fine a trolley line as one can find in the North, theatre, bank, almost everything of consequence, are chiefly due to these gentlemen. The Mississippi Sound oyster is sold under thirty-five different labels from this one factory, part of these being private labels that have purchased them.

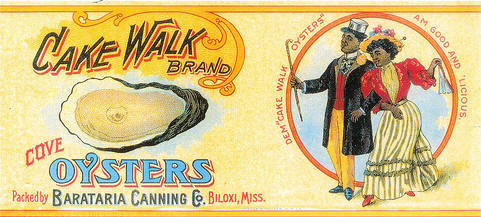

The Barataria Canning Co. is one of the largest industries on the Gulf Coast, and its product is sent over the world – oysters, shrimp, figs and vegetables. Several hundred hands are employed in the factory, and on the boats. Thirty-five oyster ships are operated by this company. The capacity of this factory in oyster canning is 2,000 barrels a day.

Alma Alves was born in Louisiana on July 8, 1907, the daughter of Peter Alves and Angelina (Trasierra) Alves. The family moved from New Orleans to Biloxi about 1910. They had ten children, two who died very young. The youngest, and the last to die, was Wilhemina, who passed away in 2005 at the age of 95.

In the 1920 census, Alma, then about 13, was listed as attending school and not working. Her father was unemployed due to illness, and her mother was working as an oyster shucker. Alma married Voorhis Olier in about 1926. In the 1930 census, they are living with her mother, but her father is not listed in the home. Alma is working in a seafood cannery, and Voorhis is working as a boatman.

Edited interviews with Joseph Olier, son of Alma Alves, and Joseph’s wife, Patricia Olier. Interviews conducted separately by Joe Manning (JM), both on September 23, 2009.

Joseph Olier

JM: What did you think of the pictures?

Joseph: I’d seen one of them before, the one with the family. It was in the Biloxi-D’Iberville Press five or six years ago. I had never seen the other one of my mother until you sent it to me. I sure was surprised. I didn’t think I would ever see something like that. I had cut out the one that was in the newspaper and put it in a frame, but Hurricane Katrina got it. It took my home and everything.

JM: Did you rebuild your home?

Joseph: No, I bought one somewhere else. They had wanted to rebuild my house 18 to 20 feet off the ground, but it would have been too expensive for the insurance.

JM: So when I sent you the pictures, I guess I replaced the one you lost.

Joseph: That’s right. Actually, I had recently been thinking about seeing if I could get another copy from the newspaper, but then you sent it.

JM: When the picture was in the paper, did you let them know your mother was in it?

Joseph: No, I didn’t do that.

JM: Were you surprised to see your mother and your family in that situation?

Joseph: I kind of figured it was like that back then, because I remember my daddy talked about how bad it was when he was little. He lived in Louisiana and had to cut sugar cane and plant rice and stuff like that.

JM: Mr. Hine took these pictures in order to convince people that there should be child labor laws.

Joseph: Well, that was a good purpose. It was hard times back then. That house they were living in looks like a rundown shack. I’d seen some of those shacks down in Biloxi when I was a kid. You could see through the walls when you went in them. My daddy lived in a shack when he was little.

JM: Did your mother ever talk about this?

Joseph: No.

JM: Did you know Peter Alves, your grandfather?

Joseph: No, he died before I was born. I knew my grandmother when I was little.

JM: When were you born?

Joseph: 1939.

JM: Where was your family living then?

Joseph: I was born in my grandmother’s house on Myrtle Street, in Biloxi. We lived with her for a while, and then we lived in a project in Biloxi. The projects were homes for people who didn’t have much money. We paid about $15 or $20 for rent.

JM: What did your father do for a living then?

Joseph: He worked in the shell mills. They’d grind up shells and make bricks out of them. He also worked in other factories, and finally went to work for the USO (United Service Organizations). He was a maintenance man. He also worked for the church.

JM: Did you mother work when you were growing up?

Joseph: Yes, she worked in the factories. She picked shrimp, opened oysters, things like that. She’d get up about 3:30 or 4:00 in the morning. She’d get home late in the afternoon, depending on how many boats they had to unload.

JM: How many children did she have?

Joseph: Five. Two of them, a brother and a sister, died of pneumonia at about a year old. I didn’t even know them. I’m the only child left.

JM: Who took care of all of you when both your parents were working?

Joseph: My grandmother, Angelina, as far as I can remember. That’s my mother’s mother. She lived about five blocks from us until 1947, when we bought the house next door to her. That’s when we moved out of the projects.

JM: What was the address of that house?

Joseph: The old address was 219 Myrtle Street. Then it was changed to 129 Myrtle.

JM: Was your mother still working then?

Joseph: Yes, and my daddy was working for the USO then.

JM: Have you lived all your life in the Biloxi area?

Joseph: After I got married, I also lived in Louisiana and Texas. I live about 25 miles from Biloxi now.

JM: Do you ever go back to see the house on Myrtle Street that your parents bought?

Joseph: It’s not there anymore. The hurricane took it. It was a block and a half from the water. Katrina cleaned out the whole point down there. They call it Point Cadet. The only thing that’s down there now is casinos.

JM: Oh, so you were living in your parents’ old house when Katrina came?

Joseph: Yes. I still own the property, but there’s nothing going on with it right now.

JM: What was your mother like?

Joseph: She was a hard worker, both her and my daddy.

JM: Did your parents have a lot of friends?

Joseph: Yes, until they got to be 70 or 80 years old. My daddy used to throw all kind of fish fry parties at the house.

JM: When did your daddy die?

Joseph: In 1983. He was born in 1902. My mother was born July 8, 1907, and she died September 1987. My father’s first name was Voorhis, and he was Acadian. That means he was French. My mother was Spanish. She looked like a Spaniard.

JM: Was there anything your mother liked to do when she wasn’t working?

Joseph: She liked to work in her garden. She planted flowers all around the house. My daddy planted a huge garden every year, with tomatoes and potatoes. My mother liked to cook. She’d make gumbo, and meatballs and spaghetti.

Patricia Olier

JM: What was your reaction to the pictures?

Patricia: It sure pleased my husband to see what his mother looked like. If you look at Joe, the boy in the family picture, it’s just like you’re looking at my husband, the dark hair, the dark olive complexion. You could tell it was a hard life that they had.

JM: Did Alma ever talk to you about that?

Patricia: No, she never did.

JM: Were you aware of the poor conditions she was living in then?

Patricia: No. I knew she was raised working in a factory, but I didn’t know it was at such a young age that they started teaching them the trade.

JM: What was Alma like?

Patricia: She had her good moments and her bad moments, as most mother-in-laws do.

JM: What were the good moments?

Patricia: We lived away a lot, but my husband would go get them every Christmas, and they would stay with us until January or February. Neither one of them drove. We all had a good time then. I got along better with my father-in-law than I did with Alma. You gotta remember, I married the youngest son. He had been married to someone else before me. He had gotten married when he was in the Navy. By the time I met him, he had already been divorced a long time. He had a daughter with his first wife. I think his mother always wanted him to go back to his first wife, because of his daughter. But when we had a son, her attitude changed, somewhat.

I think she had a good life. She worked hard. I’m not sure when she quit the factory. She worked there a little bit after Joseph and I got married. And then she started doing housekeeping at the Trade Winds and the Sun and Sand (hotels). She worked at the USO when my father-in-law worked there. I think she made sandwiches and stuff like that in the kitchenette. When they worked at the USO, they had a lot of the guys coming in, and she would take in their laundry. She had clothes hanging all over the house, even outside. It really hurt when my father-in-law had to give up working at the USO. He was diagnosed with cancer.

JM: What did your husband do for a living?

Patricia: When we first met, he was running two service stations. Then we got married, in 1964, and we moved to Louisiana, and he worked on the ships on the river. And when that kind of played out, we moved to Arlington, Texas. Our daughter was six months old then, and our son was three years old. My husband went to work at a Shell station. He did that for a few years, and then he got a job doing the maintenance for the apartment complex we were living in. He was taking care of the air conditioning and the plumbing, whatever needed to be done. In 1979, we moved to Saint Bernard, Louisiana, where my dad was. I’m originally from New Orleans. We lived there for about three years, and then we came back to Biloxi, and that’s when my husband went into business for himself, as a carpenter and contractor. He built houses, fixed roofs and added on rooms. Whatever had to be done, he did it.

JM: Did he go to college?

Patricia: No, but he graduated from high school.

JM: Do you know how far Alma went in school?

Patricia: No, but I doubt that she got very far. My father-in-law couldn’t read anything. But he was a whiz at math. He could figure it out in his head before you could do it on a piece of paper.

JM: Lewis Hine used the pictures of your mother-in-law and her family to promote the passing of child labor laws. What do you think about the conditions they had to live under?

Patricia: I never would have believed it if I hadn’t seen it. We sent copies of the pictures to our son in Florida. Alma always called him her ‘Little Jesus.’ We talked to him the other night after he got the pictures, and he couldn’t believe it. We were all flabbergasted.

JM: Have you got any pictures of Alma or anyone else in the family?

Patricia: We lost them all in the hurricane. When it came, we didn’t leave with anything but the clothes on our backs and a few important papers.

Joseph Oiler (Alma’s son) and I tried together to identify each person in the above photo. It was interesting how we figured it out, so I decided to include the text of that conversation.

JM: In the family picture, can you identify the boy on the porch? Maybe August or Louis?

Joseph: August was a cousin, I think. Louis was one of my mother’s brothers.

JM: According to 1910 census, Louis would have been 19 at the time, and August would have been 17.

Joseph: I’m trying to figure out who you’re calling August.

JM: There was a son named August listed in the census.

Joseph: I had an uncle called Gussie. They also called him Sparky.

JM: I think Gussie would have been a nickname for August. Do you remember Charlie?

Joseph: Yes, my Uncle Charlie.

JM: Maybe the boy was Charlie. He would have been 14 then, and he looks like he could be about 14.

Joseph: The boy in front would be Uncle Joe. The caption says that it’s Joe.

JM: The girl who was holding the baby was probably Jennie. Unless it’s Bertha.

Joseph: No, Bertha is standing next to her. The other girl, her name ain’t Jennie.”

JM: Jennie would have been about 12 years old in the picture. She looks like she’s about 12.

Joseph: I think she was the oldest girl. The baby is Wilhemina.

JM: In the 1910 census, Jennie is the oldest girl.

Joseph: The oldest girl was named Honey. That women standing up by my mother, she’s the woman in the other picture. Both of them are in white. You notice that?

JM: I think you’re right.

Joseph: She was probably babysitting. The parents would have been working.

JM: I almost certain now that the boy with the hat on was Charlie.

Joseph: Maybe so.

Alma Alves Olier passed away in 1987 at the age of 80.

Others in the family picture above: Charles died in 1971, Wilhemina (2005), Jennie (1980), Bertha (1986), and Joseph (1953). Joseph was seriously injured on the job when he was 14 years old. His family sued the employer.

Joseph Alves

When he was 14 years old, Joseph Alvis was seriously injured while working for the Sea Food Company, at Point Cadet in Biloxi. His family filed a lawsuit, and they won. But it was appealed by the company. The edited text of that appeal is below. The company lost the appeal.

Action (1918) by Joe Alves against the Sea Food Company. From a judgment for plaintiff, defendant appeals.

Appellant operated an oyster cannery in the city of Biloxi. Its canning house was on the beach, and its wharf extended from the house out over the waters of the harbor. Schooners laden with oysters for the factory would moor at the wharf. Tracks were projected from the house running out upon the wharf upon which small crated cars, twenty-two inches wide and eighteen inches deep, with seven-inch wheels, pushed by hand, conveyed the oysters from the boats to the factory. The oysters were then steamed in the crates on the cars, causing the grease to be removed from the car wheels, necessitating the wheels being greased on each trip of the cars out when empty.

The appellee, Joe Alves, a minor fourteen years of age, was employed by the appellant to grease and regrease the wheels of these empty cars on the wharf while they were stopped and awaiting transfer to the loading track to be loaded from the schooner moored at the wharf. While the appellee was serving appellant in this capacity on the wharf, he stepped into a hole in the wharf which caused him permanent injury. This hole was about six inches wide and twelve inches long, and was used by appellant as a slot with a wire cable running through it, which connected with a derrick that lifted the oysters, in baskets, from the boat into the cars. The hole was open and unguarded until after the injury occurred. The case was submitted to the jury on the question of whether or not the master was guilty of negligence in failing to provide the servant a reasonably safe place in which to work, and there was a verdict and judgment in favor of appellee, from which this appeal is taken.

The appellant contends that the lower court erred in not granting a peremptory instruction to the jury to find for the defendant below, and urges three reasons in support of his position: First, it is not liable because appellee was not engaged within the scope of his employment at the time he was injured; second, there is no liability, because appellee failed to show the negligence of appellant, and the risk was assumed; third, appellant is not liable, because appellee knew the hazardous situation and knew of the presence of the hole and willingly stepped into it.

The testimony in the record shows that it was the duty of appellee, Joe Alves, to grease the cars at any point at which they might stop on the wharf, and that the cars, when empty and ready to be greased, were not put at any particular place on the tracks but were left wherever they were shoved to, and when he did grease a car he would transfer it to the loading track and shove it to the proper place to be loaded from the schooner. On the occasion when appellee was injured he was serving within the purpose of his employment in waiting upon the wharf to grease the next car when empty. He would grease the cars all along the track, wherever they might stop, the performance of his duty requiring him to walk over and along the track on the wharf. At the time he was injured there was no car to grease, and he had gone over to another employee who was operating the derrick and asked him if he needed another car, it appearing that it was appellee’s duty to shove such car to the proper place for loading if needed, and the operator of the derrick informed him that he did not need another car at that time. Appellee then turned to walk back to the “steam box,” and as he walked along the track he stepped into the hole, through which the steel cable was being operated in hoisting oysters from the boat, and his leg was caught and mangled, resulting in very serious and permanent injury. The day the injury occurred was the first day that the appellee had worked on the wharf, and he had not been instructed of the dangers, nor had he been instructed to remain at any one particular place for the purpose of greasing the cars, but was given general instruction to grease the cars wherever they might be standing on the tracks.

There is testimony in the record tending to show that appellee at the time he was injured was not engaged in any independent pastime, but was in and about the master’s business; that is, he was not playing, nor engaged about any matter outside of the duties and scope of his employment. Therefore we think that, while the appellee was not actually engaged in greasing the cars for the master at the very moment when he was injured, yet he was in the employment and about the master’s business at a place incidental to his work, where he had a right to be as a servant employed to do that particular character of work, when he stepped into the hole and was injured.

The second contention is that the master was not guilty of negligence because the place in which the servant was working was a reasonably safe place. In other words, that having the dangerous and unguarded hole in the wharf, with the cable running through it, put there and maintained by the master, was not negligence. We cannot agree with appellant in this contention. Under the facts and circumstances of this particular case, it clearly appears to us that the master was negligent in establishing and maintaining an unsafe place in which this inexperienced boy was required to work. To say the least, it was undoubtedly a question of negligence vel non to be submitted for the determination of the jury. The record shows that after the injury occurred the master boxed and guarded the hole so as to make it safe to persons and employees who had to walk along and about the tracks on this wharf in the performance of their duties. Of course, the fact that the master remedied the dangerous condition after the injury occurred is not an admission of negligence, but is to be considered only in determining whether or not the master was guilty of negligence in the first instance in not boxing or guarding the dangerous hole so as to prevent injury to persons employed there who might step into it. It was not necessary to leave the hole open and unguarded in order to effectively carry on the work of hoisting and loading the oysters, because the wire rope ran through the hole perpendicularly, and the derrick and wire pulley could be operated as well when the hole was boxed up or guarded as when it was open. It may be true that the appellee was guilty of contributory negligence in stepping into the hole, but his .contributory negligence cannot defeat his cause of action if appellant is guilty of negligence, but should be considered only in diminishment of the damages. It is also true in this case that the appellee knew that this hole and several other holes, of the same kind and character and used for the same purpose, were there on the wharf, yet this would not bar his right of recovery if the master was guilty of negligence in failing to furnish the servant a safe place in which to work.

“The duty of the master extends to preventing the premises upon which he requires the servant to work from containing dangerous pitfalls, holes, obstructions or other mantraps, in which his servant is liable, unguardedly, to fall, while his mind is absorbed in the duties of his employment, or during momentary forgetfulness of the presence of the danger.” City of Natchez v. Lewis, 90 Miss. 310, 43 So. 471.

As to the third contention of appellant, in which he invokes the doctrine of volenti non fit injuria, we think that the principle is inapplicable in this case. It does not appear from the record that the appellee willingly or of his own volition stepped into the hole, nor was he injured by his own consent, and there is no assumption of risk in this state, where the master is guilty of negligence.

The lower court was liberal in granting instructions to the appellant properly submitting to the jury the questions of whether the appellee was acting within the scope of his employment at the time he was injured, and whether or not the master was guilty of negligence in failing to furnish a reasonably safe place in which the servant was required to work. Taking the record as a whole, we are unable to find any reversible error in the case. The verdict of five thousand dollars is not grossly excessive. The judgment of the lower court is affirmed.

Joseph Alves was born in 1903. He married Mable Marie Tauzin. They had four children. He died on October 19, 1953. Mable died on May 27, 2004. They are both buried in the Biloxi City Cemetery.

*Story published in 2009.