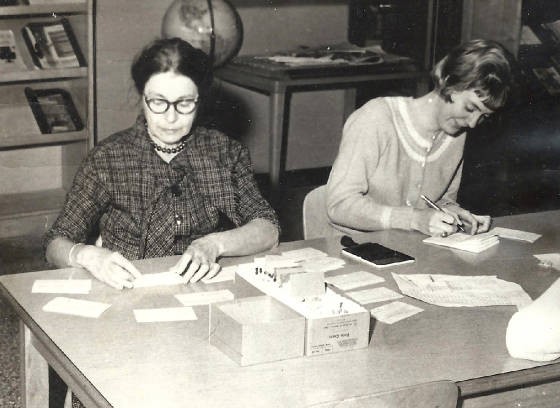

Lewis Hine caption: Betsey Price, First year high school at her Club sewing. 4 H Club work, Marlinton, W. Va. Location: [Pocahontas County]–Marlinton, West Virginia / Photo Lewis W. Hine, October 7, 1921.

“I don’t know if that was why her picture was taken, but my mother was really pretty. My dad told me that when he saw her for the first time, she was so beautiful, that he fell in love with her right away.” -Elizabeth Blake, daughter of Betsy Price

People familiar with Lewis Hine’s child labor investigations might wonder why he took this photograph for the National Child Labor Committee. Betsy is well dressed, even fashionable, and quite grownup looking for 13. And she is sewing for the 4-H Club in her high school, not for some rich textile mill owner in his lint-filled brick building by the river. It was taken in 1921, not in the years between 1908 and 1917, when Hine took nearly all of his classic child labor pictures. To learn more, I contacted Tom Beck, chief curator of the Special Collections Department of University of Maryland, Baltimore County. The collection includes nearly all of Hine’s child labor photographs, and Beck is regarded as an expert on Hine’s work.

He told me that West Virginia established a Child Welfare Commission in 1921. At that time, the state had stiffened its laws requiring school attendance for children between 14 and 16. “Like other locations where Hine was sent to photograph,” he explained, “the state was in the midst of changing their laws regarding child labor. The National Child Labor Committee would have wanted Hine to highlight the state’s efforts.”

Shortly after, I found the following, which I have excerpted from Rural Child Welfare, An Inquiry by the National Child Labor Committee (1922), based upon conditions in West Virginia, under the direction of Edward N. Clopper. Photographic illustrations were by Lewis W. Hine.

“In the beginning of our agricultural development it was necessary that every member of the family be a producer to his greatest capacity. Families lived far apart, seasonal help was scarce, and the labor of the whole family was necessary to save the crop. The family that did not produce to its utmost was looked upon as a drag on the community. A child who spent his time in play was not only of no benefit but was thought to be on his way to ruin. Work kept adults out of mischief, so why was it not good for the child? Rural folk are slow to change from old to new ideas. Many children are still compelled by their parents to work, not from necessity, but because they honestly believe that work is the only thing worthwhile for them. They are prejudiced against play, recreation, and social life, and cannot see the value of an education if it interferes with their immediate needs, so they often require children to work to keep them out of devilment. On the other hand, there is still severe economic pressure on many rural homes which, without relief from other sources, demands the undivided attention of every member of the family.”

“The parent’s conception of his relation to his child is another factor influencing the kind and amount of work the child does. The popular conception in the rural mind is that the child is indebted to the parent for bringing him into this world, that it is the child’s duty to make every sacrifice for the parent, that where the interests of the child and the parent conflict, those of the former should always be sacrificed.”

“The work done by children on the farm presents no difficulties to the mind of the rural parent. In conversation with a man who was a leading farmer and an active church and Sunday School worker in his community, one who had more than an average education and appreciation of present-day problems, in fact a man who was the leader of his prosperous community, this question was asked: ‘Do you think the children in this community are in any way injured by the work they do on the farm?’ Answer: ‘No, indeed, more work would be better for them and the community would be more prosperous.'”

“The state, on the other hand, has taken a somewhat different attitude. It regards its children as future citizens, who must be given the chance of normal development so that they can take their proper places later on. The state believes that all is not well now with the rural child and is taking steps to relieve him of the burden it thinks he is bearing. Knowing the individualism of the rural father and how he insists on being lord of his household, it is not taking measures of compulsion, but is trying to displace child labor with something better – it is substituting children’s work for child labor, but it is often hard to distinguish between them. Child labor interferes with health, education, and recreation; children’s work not only does not interfere with these but aids in securing them to the child.”

“West Virginia, through its Division of Extension, is offering children’s work in the form of boys’ and girls’ Four-H Clubs. These clubs have been in successful operation for about ten years. Their emblem is a four-leaf clover, each leaf representing one essential part of a child’s life. It means luck, and luck comes to the boy or girl who has his Four H’s, namely, ‘Head,’ ‘Hand,’ ‘Heart,’ and ‘Health,'” all well developed. Clubs are organized in counties which employ agricultural, home demonstration, or club agents. They center around the local schools, and often the children from two or three schools will be organized in one. Any rural child between the ages of 10 and 18 years may become a member, if he will meet certain requirements.”

Hine took 110 photos in West Virginia in October of 1921. About 40 were of children participating in 4-H Clubs around the state. Others showed children attending rural schools, and a few showed rundown shacks and cabins inhabited by poor farm families or coal miners. He took two photographs of Betsy.

Lewis Hine caption: Betsay [i.e., Betsey] Price, – First year High School at her club sewing. 4 H Club work – Marlinton, W. Va. Location: [Pocahontas County]–Marlinton, West Virginia / Photo by Lewis W. Hine, October 7, 1921.

Elizabeth “Betsy” Price was born March 17, 1907, in Marlinton, West Virginia. She was the oldest of five children born to Calvin Wells Price and Mabel (Milligan) Price. They married in 1906. Their only son died at the age of eight. According to the West Virginia Encyclopedia, Mr. Price was the longtime owner and editor of the Pocahontas Times in Marlinton. His father had purchased the newspaper in 1892. Calvin took it over in 1906. He was a widely known journalist and conservationist. In 1954, the Calvin W. Price State Forest was dedicated in his honor. When he died in 1957, his daughter, Jane Price Sharp, became the editor and held the position until her retirement in 1981.

Given Mr. Price’s accomplishments and reputation, it is likely that Betsy and her three sisters would not have worked at a young age and would have completed high school, even if the progressive child labor and school attendance laws had not been passed by West Virginia in 1921. So in retrospect, Betsy was not a good example of what Hine was trying show; although at the time, those seeing Betsy’s photograph would not have known that.

Betsy did, in fact, complete high school and then graduated from the College at William and Mary in 1929. For most of her career, she was a librarian. She married John Branch Green in 1929, and they had two children, Elizabeth and John Jr. She passed away in Richmond, Virginia on February 12, 1992. The following is from her obituary in the Richmond Times.

“Mrs. Green, the first librarian at St. Christopher’s School, died Wednesday. She was 84. Before she joined St. Christopher’s in 1933, the school was not accredited by the Southern Association of Secondary Schools because it lacked a working library. Mrs. Green, who had been librarian at Washington and Lee High School in Arlington, left that post to establish a library at St. Christopher’s. She catalogued books, secured reference materials and introduced the Dewey Decimal system to the library, which met accreditation standards within months.”

Excerpts from my interview with John Green, son of Betsy Price. Interview conducted on March 5, 2011.

“When my parents got married, they kept it a secret for a while. My dad was a teacher at St. Christopher’s School, a private school in Richmond. My mother was a librarian in Washington. Dad was afraid that if they got married, he would get fired, because the school didn’t want teachers to be married. Finally, my father proposed to the school that my mother come to the school and start an accredited library there. When the school agreed, my father announced that they had gotten married.”

“My mother and father lived through the Depression. I remember her talking about those years. She said she would go to the grocery store with a little change in her pocket and see what she could afford. My mother sewed a lot of things. My wife often mentions that my mother used to save thread. My parents were very frugal, very thrifty. My mother played the piano at the school’s religious services. She played off and on all of her life, and Dad played the banjo.”

“I was born in 1944. My mother was 37 years old then. I graduated from Old Dominion University, with a degree in geology. I worked most of my life in the oil and gas industries. My wife and I left Virginia in 1972. We moved around a lot because of my career, and finally settled in Colorado. We would go back home every year to visit my parents, because they wouldn’t travel. They came out here once, in 1982. My father had never been on an airplane up until then. He was afraid of flying.”

Edited interview with Elizabeth Blake (EB), daughter of Betsy Price. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on February 25, 2011.

JM: What did your mother’s father do for a living?

EB: He was editor of the Pocahontas Times, in Marlinton, West Virginia, which is a very small town. He was a very influential person. There’s a state forest named for him, the Calvin W. Price State Forest. He was very interested in conservation. One of his brothers was a lawyer, and another was a doctor.

JM: Did your mother go to college?

EB: She went to the College of William & Mary, and then did graduate work in library science at the University of Virginia.

JM: What did she study there?

EB: She majored in education. She met my father there. His name was John Branch Green. They were married in Washington, DC, in 1929. She was a librarian there, at Washington and Lee High School. He taught at St. Christopher’s School in Richmond, Virginia, which was an Episcopal school for boys. That was at the beginning of the Depression. At that time, only one person in a family was supposed to be working, so they kept it a secret for a while. She got a job as the librarian at the school. We lived at St. Christopher’s until I was about 15. They had apartments for the teachers. We had all our meals with the boys at the school. My mother liked that, because she didn’t have to cook.

JM: How many years did she work for the library?

EB: Until I was about 10 or 11. My father taught there for about 25 years.

JM: What year were you born?

EB: 1939.

JM: How many children did your parents have?

EB: Just me and my brother, John Branch Jr. He’s about five years younger than I.

JM: Did you go to college?

EB: I went to Flora MacDonald College for a couple of years, and then I went to nursing school. I worked as a nurse until my children were born.

JM: Did your mother ever move back to West Virginia?

EB: No. But she loved it there.

JM: Is the house she grew up in still standing?

EB: Yes it is. Her sister, Jane Price Sharp, still lives there.

JM: How many brothers and sisters did your mother have?

EB: She had three sisters, and one brother that died at birth.

JM: Where was the last place that she lived?

EB: In Richmond. After we left the school, we moved into a house. My father had resigned from St. Christopher’s, and had gone into banking. My mother taught at J.R. Tucker School and Hermitage High School.

JM: Was she in good health most of her life?

EB: Not really. She was a heavy smoker. She got emphysema. By the time I was in high school, she was already having some breathing problems.

JM: What was your mother like?

EB: She was a very warm person. She loved music. Her father wanted all his daughters to be teachers, but I think she would have preferred to study music. She a very good at playing the piano, and she could compose.

JM: What are some of the things you and your mother did together when you were growing up?

EB: We went to a lot of concerts, like the chamber music concerts at the University of Richmond. I enjoyed that. I took piano lessons when I was young. As a family, we usually went back to West Virginia in the summer. At one time, my dad had a camp up in Maine, and sometimes, we would stay for the whole summer.

JM: How did you find out about the photographs of your mother?

EB: My mother had them, and when I married, she gave them to me.

JM: Did your mother ever say anything to you about the photographs? Did she remember being photographed?

EB: I think she did, because we had those pictures as far back as I can remember. I don’t know if that was why her picture was taken, but my mother was really pretty. My dad told me that when he saw her for the first time, she was so beautiful, that he fell in love with her right away.

Betsy Price: 1907 – 1992

*Story published in 2011.