Lewis Hine caption: Capps family at Columbia vaudeville. Baby of 21 months (been on stage for 6 months). Girl of 5 years (been on stage for 2 years). Boy of 7 years (been on stage for 1 year). Girl of 8 years (been on stage for 5 years). Boy of 12 years (been on stage for 8 years). Boy of 14 years (been on stage for 9 years). Oldest boy is acrobat, contortionist, etc. All do singing and dancing acts except baby, who appears in final scene as Charlie Chaplin. They appear 3 or 4 times a day–sometimes 7 days in the week, usually coming last on program (as a feature), which means they do not leave dressing room until nearly 11 p.m. Then, in addition, the life in cheap hotels and on the road “making new towns” is very unsettling. It was very touching to see the little ones curled up back of the scenes waiting for their act and getting 40 winks or the mother nursing the baby just before it was poked out onto the stage to do his little “turn.” In spite of their stage life, their manners are good. They are quiet, well-appearing children, and the parents are kind and sympathetic. The father acts as nursemaid to the baby, and the mother dresses and changes the others and appears herself. She said: “They’re never sick. It’s the healthiest kind of life.” The 8-year-old girl said: “I don’t like it–the men in some places are so rough.” There was some familiarity shown to them, but not much. Location: Grand Rapids, Michigan / Lewis W. Hine, November 29, 1917.

“I was born in a hotel. My family was traveling on the vaudeville circuit at the time. My sister Dolly was born in a taxi cab, and my sister Bee was born in a streetcar.” -Everett (Jimmy) Capps, youngest child in the Capps Family (not in photo)

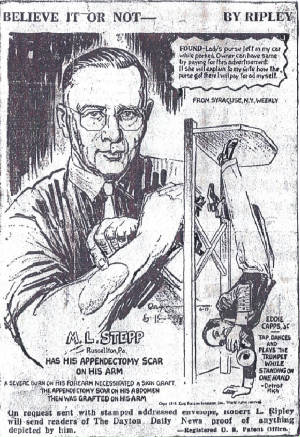

“My dad was in Ripley’s Believe It Or Not, for an act that he did. He stood on one hand and tap danced on a prop while he accompanied himself on the trumpet. They were kind of crazy, you know, real daredevils. They would do handstands on the top of the Empire State Building and the Eiffel Tower, and dive off bridges without knowing how deep the water was.” -Barbara (Bobbi) Toro, daughter of Edward Capps Jr.

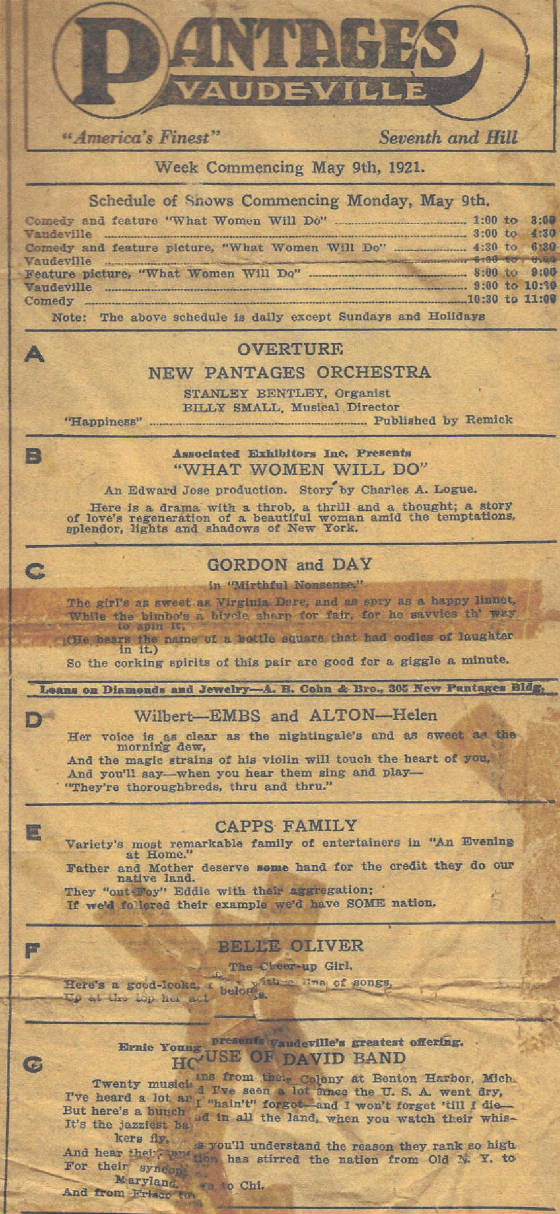

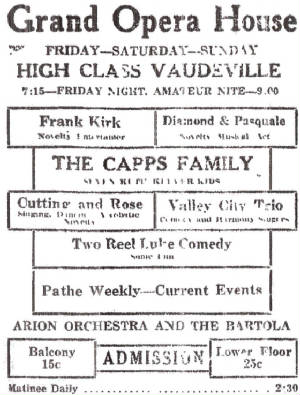

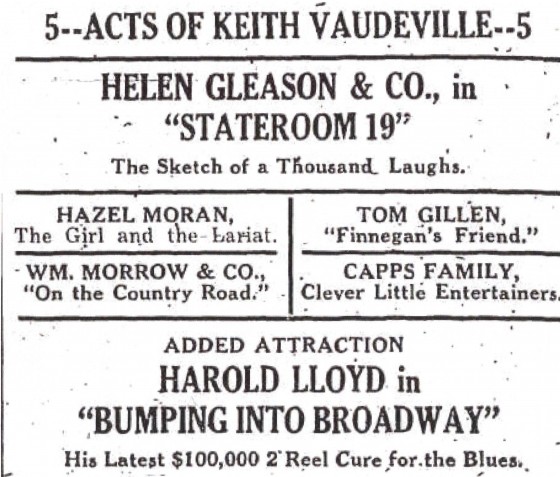

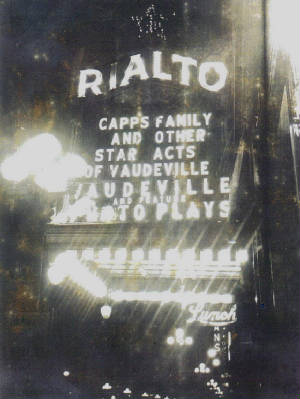

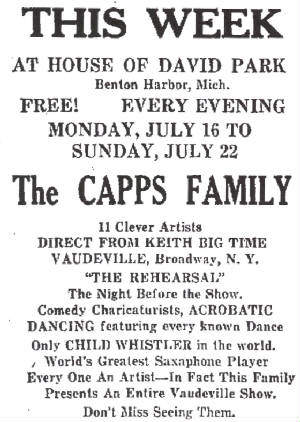

“The Capps Family, eight in number from the toddler of three to the proud mother and father, are a happy lot who have something in the way of entertainment that is out of the beaten path, a novelty in laughter, song and dance that scintillates with the spirit of youth. Vaudeville has had its share of family acts in which precocious kiddies have been featured and have made good. Several acts of this nature have, however, carried two or more children who while appearing did not contribute to the act in entertaining. In the Capps Family, everybody works, the sextet of kiddies contributing individual numbers that are altogether worthwhile, specialties that will delight the little folks and make the old ones feel young again.”

“As the curtain slowly rises, the octet is heard in an ensemble singing a number which serves to formally introduce this clever family. Following the opening, two of the children, a boy and a girl, offer a pretty singing and dancing number which in turn is followed by a vocal solo by another boy whose rendition of same is most worthy. Then we have the most versatile of the male portion of the family in a display of magic, music and acrobatic dancing. The female portion, not to be overlooked now have their innings as one of the girls presents a character song which is followed by another young Miss attired in full evening dress clothes, impersonating one of the male sex singing a characteristic song. Then a trio consisting of two boys and a girl offer a clever dance, the closing number showing all six children offering homage to their parents. The audience invariably voices their hearty approval and never fails to express empathetic appreciations for the wonderful Capps Family.” -Owosso Argus Press (Michigan), October 9, 1919

**************************

“Eldridge T. Gerry sailed for Europe on Wednesday, but before taking passage, he instructed the agents of his Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, in this city, to oppose all applications for the use of children in stage performances during the summer. Mr. Gerry still believes in the arguments presented by him to Mayor Strong the other day, that theatrical employment during the warm weather is physically harmful to children, and as a result of this, all applications made by the city managers have been refused by Mayor Strong, after the Gerry Society has filed it formal objections.” –New York Times, June 7, 1895

Sixteen years after the above article was published, Jean M. Gordon made a presentation called “Child Labor on the Stage,” at the Seventh Annual Conference of the National Child Labor Committee. The following is an excerpt:

“There is no phase of child labor which I have found in my four-and-a-half years’ experience as factory inspector in the City of New Orleans so baneful as that of the children of the stage. We became impressed with the subject of the children in the mill, because we could see those hundreds of little children coming out every evening after a hard day’s work. I do not think many of us have realized the enormous growth of the nickel show and the vaudeville theatre, or the number of children employed in them. My work as factory inspector brought me in touch with the theatrical situation in New Orleans. I did not find any talent displayed in the girls that I had to take off the stage. They were simply employed for their physical attractiveness. In my office I have learned from girls of ten and twelve and thirteen years of age, of the low standard of morals taught these young children as part of their stage experience.”

“The state has said that no girl under twenty-one years of age can have charge of her money. But you allow a little girl of ten years of age to take her moral life in her hand. You may think that this is all very true, but that art is a hard taskmaster, and genius must be given a certain sway. Theatrical people have a great way of talking of the geniuses. I think I am more interested in helping the geniuses along than any of the others, because I fear that those with any real genius in them would soon have it blotted out by the contact with the life they lead.”

“It is only the human family that lives off the earnings and the wages of its own little children. They tell us that they always take such excellent care of the stage children. Stage children of five and seven years were boarded in a place in New Orleans where, I believe, no respectable parents would care to have their little five and seven-year-old children stay; going home as they did at half past eleven and twelve o’clock at night.”

**************************

Lewis Hine took only three pictures of children working in vaudeville or the theater. In one of them, taken in Philadelphia in 1910, Hine wrote a lengthy caption:

“This picture shows the ‘Four Novelty Grahams’ acrobatic performers at the Victoria Theatre, Philadelphia. The father is 23 years of age. Willie Graham is 5 years of age, and Herbert Graham is 3 years of age. At 9 P.M. on June 10th, 1910, these children were performing on the stage. Four times daily they do a turn which lasts from 12 to 14 minutes. Herbert Graham, the youngest, was said by the father to have commenced performing on the stage as an acrobat when he was 10 months of age. Willie, now 5, is said to be the youngest acrobat in the world. The attached letter head shows some of the stunts these youngsters are engaged in. The mother of these boys was formerly a school teacher, and is now performing with this trio on the stage. The children are bright and strong, but have a playfulness about them which shows them to have forgotten the best years of childhood.”

According to the Hine child labor collection at the Library of Congress, Hine’s final photograph of a vaudeville family also has the distinction of being the very last picture he took for the National Child Labor Committee between the years of 1908 and 1917, which was the period when he did his most significant work. In 1918, he landed a job with the American Red Cross, documenting WWI refugees in Europe. He went on to take several hundred more photos for the National Child Labor Committee between 1921 and 1924, 95 of which were child laborers.

When I started my research, I had difficulty finding the family in the census, so I hunted for them on newspaper archive websites and other Internet sources. I found a few old newspaper articles and other items about the family, but no indication that they were very famous, or that anything substantial had been written about them. I got lucky when I discovered a brief posting by Ms. Bobbi Toro on an online genealogy forum. She gave her contact information, so I emailed her about the photo and my research, and received this prompt reply.

“Thank you for your interest in my incredible family. I am the daughter of Edward Capps, the little boy in the center of the picture. I am aware of the photo of my father and his brothers and sisters and my grandparents and would love to correspond with you about them. The youngest child, Jimmy, who is not in the picture, is in his 80s and lives in California. Hope to hear from you soon.”

Ms. Toro followed up by sending me many photographs of her family and many newspaper articles about them. I interviewed her and her Uncle Jimmy, the youngest member of the Capps Family. As I write this, it has been 93 years since Hine photographed the Capps Family, I feel privileged to be able to tell some of their story.

All photos and images in this story provided by Bobbi Toro, except where noted.

Edited interview with Everett (Jimmy) Capps, youngest child of the Capps Family. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 13, 2010.

JM: When were you born?

Jimmy: 1924, in Saginaw, Michigan. My real name is Everett, but I go by my nickname, Jimmy.

JM: Was your family living in Saginaw then?

Jimmy: No. I was born in a hotel, the Everett Hotel (Everett House). My family was traveling on the vaudeville circuit at the time. I don’t know which circuit it was. There was the Fox Circuit, the Keith Circuit, the Orpheum Circuit and a bunch of others. My sister Dolly was born in a taxi cab, and my sister Bee was born in a streetcar.

JM: I heard that when your mother had a baby, she would take about 10 days off, and then she would bring the new baby on stage in a bassinet and place it on the piano. Did she do that when you were born?

Jimmy: Probably. I heard about that.

JM: The Lewis Hine photo was taken for an entirely different reason than you might think. There are a lot of historic photos of vaudeville families, but this was taken because Hine was taking pictures of children who were working. He was trying to create support for child labor laws. The photo of your family was an unusual one for him. Almost all his pictures were of children working in mills and coal mines, or working in other jobs that were often dangerous for little children.

Jimmy: Well, we were certainly not child laborers. We were just a show business family. We weren’t ashamed of it.

JM: What are your oldest memories of being on stage and traveling with the family?

Jimmy: I don’t remember all that much about it when I was little. But I’ve seen pictures of me on the stage then, so I must have been there.

JM: When you were a kid, did you consider yourself different because you were in show business?

Jimmy: I don’t remember how I felt at that time.

JM: I think it would have been hard to make friends when you were traveling all the time.

Jimmy: Yes, it was. We played all over. We played in Montreal and a lot of places in Canada. We traveled by boat from Detroit to Windsor, Ontario, and then took the train to Montreal.

JM: How old were you when you stopped traveling with your family?

Jimmy: I’m not sure. I traveled with a sister and two brothers, Dolly, Earl and Eddie, when I was about 14 or 15.

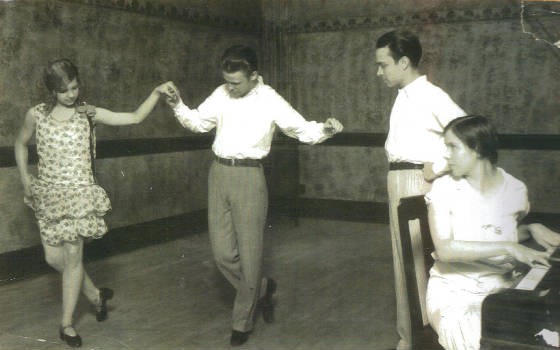

JM: What did you do on stage at that time?

Jimmy: I was a tap dancer and an acrobatic dancer.

JM: Did you dance to music played by the pit orchestra, or did you provide your own music?

Jimmy: Oh, it was the pit band. We played instruments, too, but not me.

JM: How did you learn to tap dance?

Jimmy: From my brothers. We had regular routines, and we practiced all the time.

JM: When you were traveling, were you also going to school?

Jimmy: I took correspondence courses from the Calvert School in Baltimore. I believe I did it for just the fifth and sixth grades. A lot of theatrical people used that school. I still have some of the books.

JM: When did you start attending school in an actual school building?

Jimmy: I started doing that in Oxford, Michigan. We were living in Oxford, actually in Stony Lake, which is three miles from Oxford. That’s about 40 miles north of Detroit. I finally got my GED, so I graduated. Dolly and Orville also got their GEDs, but I was the first one to do it. Some of my brothers didn’t even get as far as high school.

JM: Were you off the road at that point?

Jimmy: I don’t remember being on the road then. By that time, the family act had broken up. People had gotten married and gone in different directions. You know how it is. They start their own families. Later on, Earl and Eddie and Dolly were on the road, and they took me for a while on another circuit, not part of vaudeville, I think. It was theaters and night clubs. I was part of the act and did acrobatic tap dancing.

JM: Were there dancers at that time that you looked up to as inspiration, like Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson?

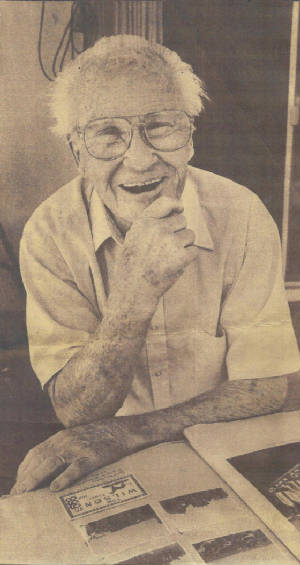

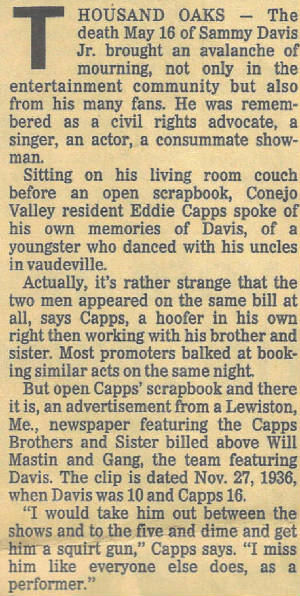

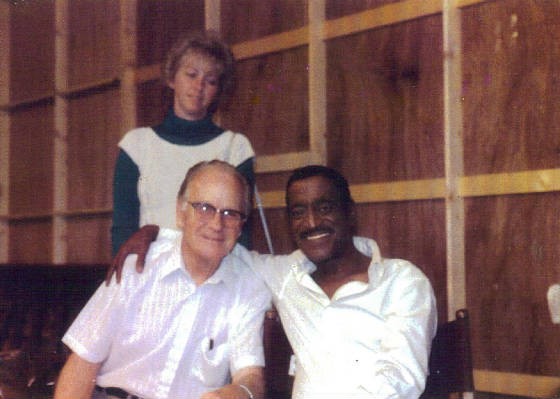

Jimmy: I had heard about him, but I never met him. I knew Sammy Davis Jr. real well. I idolized him. He did a number that was an imitation of Bojangles. We worked with him quite a bit. I used to play with him backstage. We knew the O’Connor family, you know, Donald O’Conner and his family. I worked with the Foys once.

JM: Was your family act hurt by the movies?

Jimmy: Movies ended vaudeville. A lot of the vaudeville stars went to Hollywood and became stars in the movies.

JM: Did you do that?

Jimmy: I was drafted into the service in 1943.

JM: Did you serve overseas?

Jimmy: Yes. When I came back, I went to work in Hollywood. I was in one movie.

JM: What was the name of the movie?

Jimmy: It was called Freddie Steps Out (1946). It starred June Preisser and Freddie Stewart. It was what they called a ‘B’ picture. It was made by Monogram Pictures. I was under contract with them for two weeks. And then they didn’t need me anymore. I’ve tried to get a copy of that picture, but they must have destroyed it. Maybe it was my bit in it that made them decide to destroy it.

JM: What did you do after you made the movie?

Jimmy: I worked at Fox Studios for a while, and then I taught dancing with the Arthur Murray dance schools, but that was for only about a year. Then I worked in a gas station. But I was held up one day and almost got killed, so I quit. After that, I went to work at the California Military Academy, as one of the officers supervising the cadets.

JM: Had you gotten married by then?

Jimmy: Yes, but I was divorced when I was working for the Academy.

JM: Did you have any kids?

Jimmy: No, and I never got married again.

JM: Where have you lived for most of your life since you grew up and left the family?

Jimmy: I lived in different rooms and houses in California, in whatever town I could find a job.

JM: I’d like you tell me a little about each of the persons in the photo.

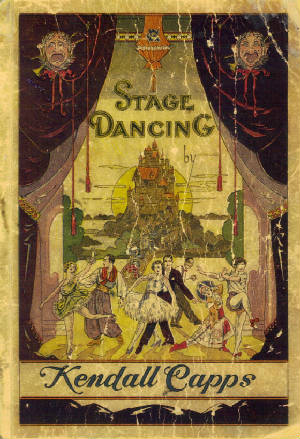

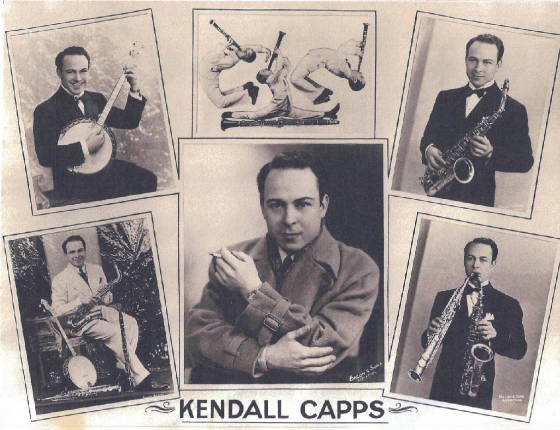

Jimmy: Kendall, Earl and Edith were the oldest, in that order. Kendall was married when he was about 17 or 18. His son was Kendall Jr., and he was born before I was. So I’m his uncle, even though I am younger than he is. Kendall stayed in show business and did a single (solo act), but the others did a family act. Kendall played the saxophone and clarinet, and he did acrobatic dancing. He was the best. He and Fred Astaire were my idols.

JM: Did you know Astaire?

Jimmy: No, but some people thought I danced like him. I was taught a routine by a dance director that directed some of Fred’s numbers. I used it in a couple of night club acts. It was pretty good.

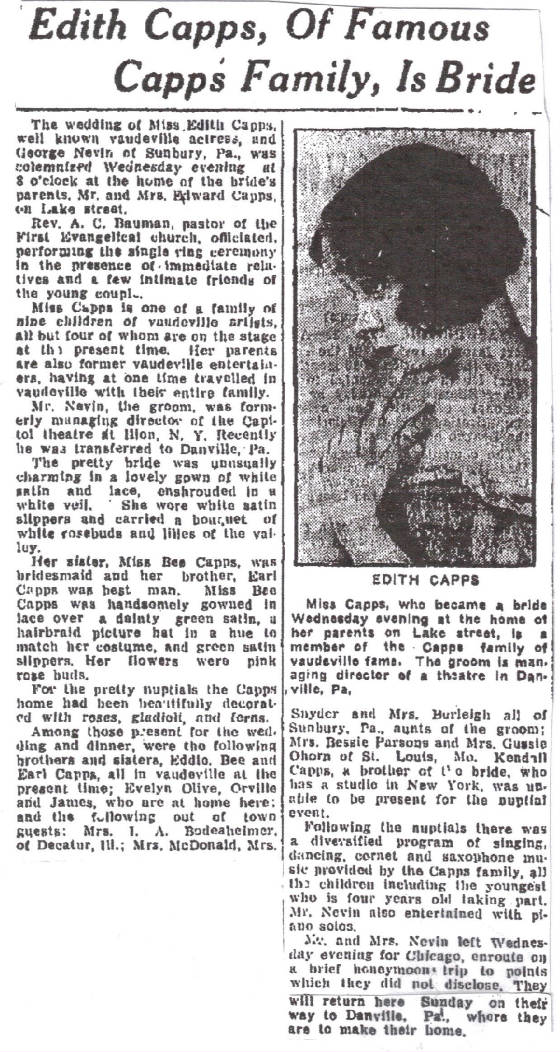

JM: Tell me about Dolly.

Jimmy: She didn’t stay in show business. She married Les Vaughan when she was living in California. He worked at Fox Studios. My youngest sister, Olive, also worked at Fox. She and Orville were in the act at one time, but not very much. They didn’t like show business. Orville was in the service. He was an electronics technician. He was sort of the brainy one in the family.

Eddie used to do a handstand on the edge of the top of the Empire State Building. I could never do a handstand. But we all had special things we did that the others couldn’t do. Earl was more or less the manager. He played saxophone and did some acrobatic dancing. When he was older, he had his own business as a cabinet maker. Edith got married and opened a dancing school in Pennsylvania. She was also a seamstress. She used to make costumes for the kids in the recitals. She was in the family act before I was born, and I don’t know much about that.

JM: What did your sister Bee do?

Jimmy: She was a dancer and singer in the original act. And she also did a whistling routine. She married Al McCaskill in Pomona and had a family.

JM: When did your mother stop going on the road?

Jimmy: That’s a long, long time ago. I don’t even remember when she was on the road. By the time I remember my mother, she’d been off for quite a while.

JM: I was told that your father was the road manager, and didn’t perform.

Jimmy: He was the manager of the original act, but Earl was the manager of the other act when I was on the road with my brothers and Dolly.

JM: What did your parents do for a living once they were no longer in show business?

Jimmy: My dad was a writer. He wrote some beautiful stories. He did a picture called Attic Of Terror (1937). It was kind of a documentary that was made in New York, under the auspices of Floyd Gibbons, who was like a soldier of fortune, like those traveling commentators such as Lowell Thomas. My father was a lot older than me, because I was the last child. I never knew what he looked like when he was younger, until I saw this photo you sent to me. I was born seven years later. He was very intelligent, but I can’t tell you much more. I was never really close to him.

JM: What was your mother like?

Jimmy: She was a wonderful mother, absolutely perfect. She was a good dancer, and she was also good at sewing.

JM: Looking back on it now, how do you feel about the fact that you and your family were in vaudeville and the theater?

Jimmy: I wonder why I didn’t succeed more than I did. I should’ve been a big star. But I wasn’t.

JM: What do you think is the reason for that? Did you lack ambition? Did you not work hard enough at it? Or was it just bad luck?

Jimmy: I had the ambition. I came real close. Close, but no cigar.

JM: Do you think you might have lost some opportunities when you were in the Army?

Jimmy: That’s possible. A lot of my friends from Detroit, like Joan Leslie and Ruth Terry, became stars then. But I was in the Army. You need to have good timing, you know. With anyone, there’s a moment, just a split second, when your whole life can go in a certain direction, and whatever you decide to do then, that’s the road that you wind up taking, good or bad. But look what happened to people like Elvis Presley, how his life turned out. Have you seen A Star Is Born? I liked the Judy Garland version the best. The movie was about what Hollywood was like. It was like a factory. Judy was a star, but her life was heartbreaking. Maybe it might have been a blessing that I didn’t go that route.

JM: In show business, and also in sports, there are a lot of people who spend the second half of their lives saying, ‘I could have been this,’ or ‘I could have been that.’

Jimmy: Like Marlon Brando said in On The Waterfront. ‘I could’ve been a contender.’ That’s me. I came close, but never top banana. That’s the way life is.

JM: A lot of people who were leftover from the decline of the theater and vaudeville after World War II wound up going into early television.

Jimmy: You’re right. That’s exactly what happened. You had vaudeville and silent movies, and then you had the ‘talkies,’ and that killed vaudeville. Then came color movies, and then television. Each one was like an era, like a page in the book.

JM: In the early days of television, the networks didn’t really know what kind of programs to have on. So they had a lot of variety shows. You’d watch one of those, and they’d have an opera singer on, and five minutes later, there would be a juggler, and then a tap dancer, just like vaudeville. How come you didn’t get into that? You could’ve come on those shows and done a dance routine.

Jimmy: I never thought of that. My brother Kendall was on a few of those. He was on Ed Sullivan. He did a solo. He played the banjo. He could do anything. Eddie played the trumpet and tap danced at the same time. None of us could do that. We competed with each other. ‘You can do that, but I can do this.’

JM: So when you were not on stage, and you were not practicing, were you and your brothers and sisters still sort of performing when you were playing? Did you all go out in the yard and dance?

Jimmy: We probably did. I lived this thing.

JM: Did you remain friends with Sammy Davis Jr.?

Jimmy: No. But Sammy and my brother Eddie remained friends. Funny thing though. Sammy never once mentioned me. And I was the one who knew him more than any of them. I grew up with him.

JM: Were there others who were famous that you were friends with?

Jimmy: Jackie Cooper. He came in right after Jackie Coogan, who was a big child star. We used to play together in the Fisher Building (Detroit). He used to have an act where he would sing and his mother played the piano. Later on, he did a few pictures, and then went into television.

JM: In later years, did you often get together with the family and talk about those days?

Jimmy: We talked about that when we got together, but that wasn’t too often. I’m the only one left now.

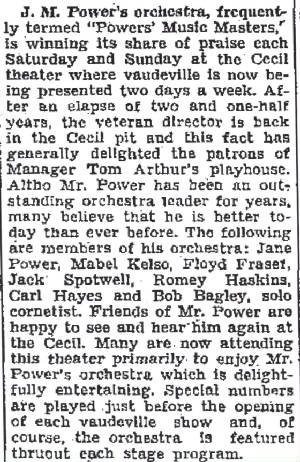

JM: My grandparents were in vaudeville. In fact, for many years, my grandfather was the conductor of the house orchestra at the Cecil Theater in Mason City, Iowa. My grandmother played cello in the orchestra. I wonder if the Capps Family played at that theater when my grandparents were there.

Jimmy: Could be. We played just about everywhere.

**************************

After I conducted this interview, I did some research to see if I could determine if the Capps Family, or members of the family, ever performed at the Cecil Theater, and if they did, would it have been at the time my grandparents, Joseph Power and Jane Power, were there. I already have a sizable collection of articles about my grandparents from the Mason City Globe-Gazette, which I obtained from NewspaperArchive.com. I went back to the site and searched “Capps” in the archives, and came up with an article about the Capps Brothers and Sister appearing at the Cecil Theater in October of 1931. Then I looked through the articles about my grandparents and found an article from August of 1931, which confirmed that he was the conductor of the pit orchestra at that time, and my grandmother was in the orchestra. As one of my friends says frequently, “Everything is connected.”

Edited interview with Barbara (Bobbi) Toro, daughter of Edward Capps Jr. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on February 16, 2010.

JM: How did you first find out about the Lewis Hine photograph?

Barbara: I looked up the Capps Family online one day, and I found the picture. My father, Edward Jr., is the little boy in the center.

JM: Do you know that it was taken by Lewis Hine, one of America’s great photographers?

Barbara: No, I didn’t know that. That’s amazing.

JM: How old are you?

Barbara: 65.

JM: Among the people in the picture, which of them did you personally know?

Barbara: All of them, including my grandparents. In fact, I grew up two doors down from them. We lived on a street where the family had bought a plot of land in Pacoima (part of Los Angeles). They subdivided the land, and each brother built their own home, all next to each other. I don’t know how they knew construction, but all of the houses were designed and built by each one. Much of my early life was spent on my grandfather’s knee listening to stories, or listening to him sing, and play the harmonica, the banjo and the guitar.

JM: How did the family wind up out there?

Barbara: They were living in Detroit, and then about 1945, most of the family decided to come to California, probably because there were more opportunities here.

JM: Didn’t they live in St. Louis for a while? They are listed there in the 1930 census.

Barbara: That was my grandparents’ home, but they hardly ever lived there, because they traveled around the world.

JM: In the 1910 census, they were listed as living in Tennessee. Your father was listed as eight months old.

Barbara: I’ll be darned. That makes sense, because my grandfather was born in Tennessee.

JM: How did they get started in show business?

Barbara: My grandfather sold tombstones. He worked for my grandmother’s father. When he met her, she was only 15 years old, but her mother gave her permission to marry my grandfather, even though he was 10 years older. Then they had Kendall. My grandmother was already doing some dancing and things like that, and she started teaching Kendall to do acrobatics at a very young age. He was brilliant at it, so they set up shows in tents, where people would go to see him perform.

JM: When did they start going on the road?

Barbara: According to a newspaper article, he first took the family on the road in 1914.

JM: Was your grandfather part of the act?

Barbara: No. My grandfather was a promoter when he was a young man. He once put posters all over town saying there would be a show and to come on a certain date and he would “let the cat out of the bag.” People watched with curiosity as the tent went up and all the chairs were put inside. When the day came, Grandpa collected the dimes, or whatever the price was, and then went inside and proceeded to remove a cat from a bag. Then he ran very fast.

He also wrote stories. One of them was called I Slept With A Dead Man. It was made into a movie called Attic Of Terror (1937). Radio commentator Floyd Gibbons had a contest for amateur writers called Your True Adventures. Grandpa’s story won, and he got $500 and a gold watch. The movie is now in the Library of Congress. I was able to get a copy of it. The best part is at the end when my grandfather comes on and receives the prize from Mr. Gibbons.

JM: What were some of the children doing in the act? What were their specialties?

Barbara: Uncle Kendall played the saxophone, and he was a great dancer and contortionist. My father was a great dancer, too. He taught Betty Grable to tap dance when she was 13. Aunt Dolly was a whistler. She was born in a taxicab in Madison, Wisconsin, so they called her Dolly Madison Capps. Aunt Bee was born in a streetcar that was going over the Eads Bridge, so they named her Eads Bridget. Uncle Jimmy, the youngest one, was named Everett. He was born on the bathroom floor in the Everett Hotel. My grandmother would go to bed for 10 days, because that was what women did on those days. On the 10th day, she would introduce the baby into the act by putting it on the piano. My grandmother would literally put the little ones in drawers in the hotels. They made perfect cribs.

JM: How did the children go to school, if they were traveling all the time?

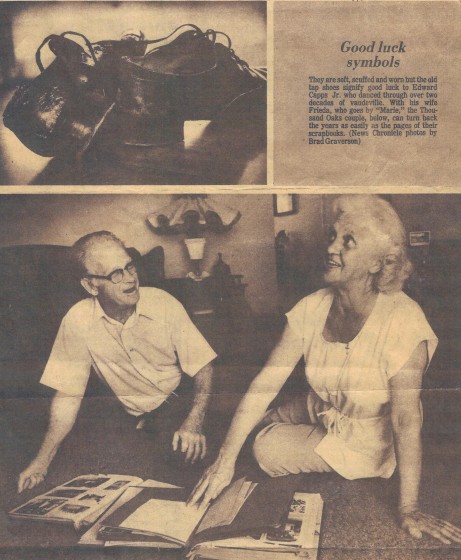

Barbara: They had tutors, and they all turned out to be brilliant. I think some of them went to school in St. Louis, at least for a while. I think my dad went up until the third grade. When they lived in Detroit, the House of David was a very important part of their lives. That was a religious organization, sort of like a cult. They didn’t belong to it, but they were all great musicians and had a band. My family lived near them. My dad was taught to play the trumpet by one of the band members. The family traveled around and played with them for a while.

JM: When did the family end the act?

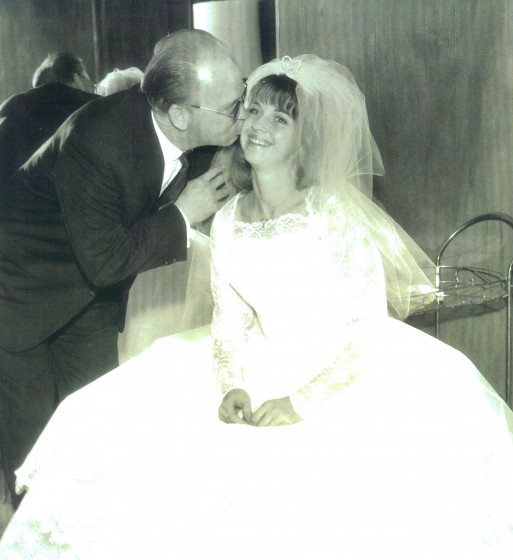

Barbara: About the time that Edith, the oldest daughter, got married (1929). Most of the children were grown, and they split off. My dad, Aunt Bee, Aunt Dolly and Uncle Earl traveled around the world with their own act. My dad met my mother, Frieda, in England at the Palladium, where she danced with the Tiller Girls, which were like the Rockettes. She was called Marie.

JM: So she came back to the US with your father?

Barbara: Not for about seven years. She stayed there with her mother, and she had a child, my older sister. My dad was selling cars in Detroit when I was born. He was once voted Salesman of the Year in Detroit. But he continued to perform until I was about 10. When we moved to California, he went to work for Lockheed, as an airplane painter, but he was still doing shows, although he didn’t travel. He worked at Lockheed until he retired.

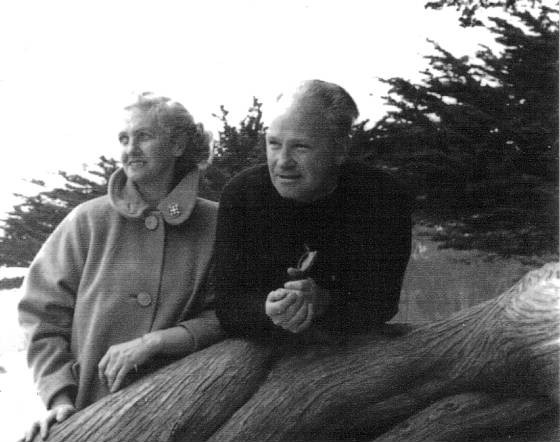

JM: When did your grandparents die?

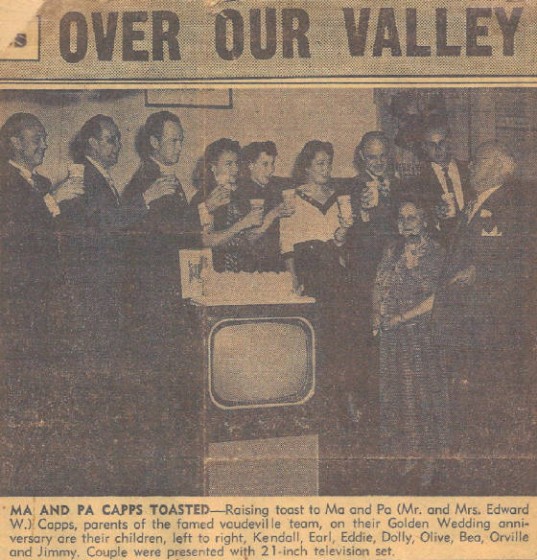

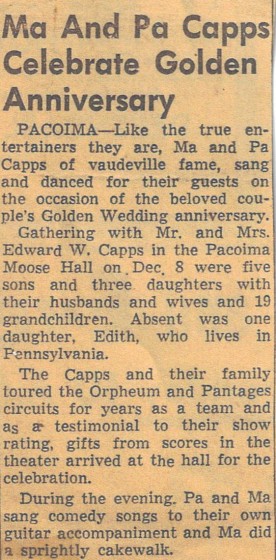

Barbara: My grandfather died on November 29, 1954, in Sun Valley, California. My grandmother died September 10, 1966, also in California.

JM: Did you ever travel with any of the family when they were performing?

Barbara: No, but I saw them put on a big show here in California at a junior high school, but it wasn’t a professional appearance.

JM: They would have been a lot older then, so I assume that maybe it was a bit different and they didn’t do as much acrobatics.

Barbara: Oh no, they pretty much did the same act. On my grandparents’ 50th wedding anniversary, they put on a big show. They rented a hall and had a lot of people there. Kendall was still doing his acrobatics then. He was incredible. He played the saxophone and did acrobatic tap dancing both at the same time. My dad was in Ripley’s Believe It Or Not, for an act that he did. He stood on one hand and tap danced on a prop while he accompanied himself on the trumpet. They were kind of crazy, you know, real daredevils. They would do handstands on the top of the Empire State Building and the Eiffel Tower, and dive off bridges without knowing how deep the water was.

“My husband, Frank, was the special effects man for Fantasy Island. In one episode, Sammy Davis Jr. was playing Mr. Bojangles. Frank mentioned that his father-in-law worked with him in vaudeville. Sammy remembered our family. My dad used to take little Sammy out for candy between shows. Sammy asked to see him. He stopped production when we came in, and he talked to my dad and looked through his photo album with him.” -Bobbi Toro

Interview with Barbara (Bobbi) Toro, daughter of Edward Capps Jr. (continued)

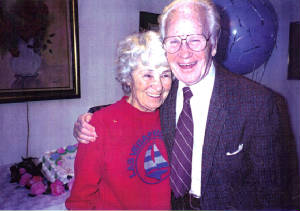

JM: When did your father die?

Barbara: In 1997. My mother died six months before him. Dad was an amazing man. He was very athletic. Until he developed hip problems in his 80s, he was walking four miles a day.

JM: What happened to some of the other children?

Barbara: Kendall went into the Ziegfeld Follies. His son, Kendall Jr., is still involved in show business, although he is also a lawyer. He’s a songwriter. Edith moved to New York and worked in the theater. Orville died just a couple of years ago. He was an excellent painter. Jimmy, who was born after the photo was taken, was an excellent dancer, and he did some film work.

JM: Are you in show business?

Barbara: No, but I’m a piano teacher, and I’ve sung professionally. I did some arrangements of old Christmas songs from other countries for a choral group. They put it out on a CD. As a child growing up in a vaudeville family, you’re constantly performing, either for the family, or for something else. My father taught me to tap dance, and he taught me acrobatics. I tried out for the Mickey Mouse Club once, but I never got into it that much. My husband was a special effects man for movie companies like Pixar. He worked on Pirates of the Caribbean. He’s retired now, but he still works freelance.

JM: How many children do you have?

Barbara: Three.

JM: Are any of them in show business?

Barbara: No, but I have a son-in-law who’s in the business.

JM: Looking at the caption that Hine wrote for the photograph, it looks like he was concerned about the lifestyle that the children were experiencing, being on the road all the time. Do you remember your father, or anyone of his siblings, talking about how rough it was to be traveling in show business?

Barbara: Never. But because they ate out every single meal when he was on the road, my dad would never take us out to dinner. He enjoyed being at home.

**************************

The following is from a speech that Edward Capps Jr. made to his church late in his life.

“I was the fourth in a family that eventually totaled nine, five boys and four girls. My dad booked amateur shows in a circuit of theaters in St. Louis and nearby Illinois. My mom was a dancer and handled the choreography end. My oldest brother, Kendall, was the first to work in the theaters, doing impersonations of Charlie Chaplin, etc. He also did acrobatic routines, and when Dad booked amateur contests, he would compete and would win practically all of the contests, not because of being Pop’s son, but because it was judged by audience applause.”

“My next oldest brother and sister (Earl and Edith) teamed up in dancing and also did well. I wasn’t very interested at that time about being in show business, being only around 6 years old, nor was my younger sister Bee and brother Orville. But my mother decided to teach us all some routines and we became known as the Capps Family. We started traveling by what is called “barnstorming,” that is, engaging school buildings, town halls, and I guess we even worked in barns (some of the places looked like barns). I still wasn’t interested in show business, but at 6 or 7, I was uneducated in any other business like engineering or being a doctor, so I went along with the act.”

“After traveling for a year or so hitting and missing, we finally got recognition and started on the big time – the Keith, Orpheum, Pantages, Loew’s, etc. This was at the same time as the Foy family. The Foys and our act were the two largest families in vaudeville. We worked with stars like Burns & Allen, Martha Raye, Snub Pollard and many more that you might not know.”

“We had a tutor for our schooling that traveled with us, and for a while, we were in the theatrical children’s school, a correspondence school that most child actors used. My oldest brother left the family to go into New York productions like the Greenwich Village Follies, Girl Crazy, etc., and the four next oldest (including me) decided to go on our own and leave the four youngest at home in Benton Harbor (Michigan). We were home very seldom. Our home was more or less a headquarters.”

“We went to New York and had it pretty rough for a while until we landed a spot on the Publix Unit, which opened in New York and took us through most of the states, and then back to New York and another unit, starting at the Paramount Theater, with Duke Ellington. After coming back again to New York, things began to slow down for us, and my brother got an offer to come here to California in a Fanchon & Marco unit. My sisters formed a double act, and their first job was at the Melody Club, with Clayton, Jackson & (Jimmy) Durante. I decided if I was to get anywhere, I would have to learn acrobatics and do acrobatic dancing instead of straight tap. So I went to a friend’s dance studio every day for about three months and taught myself flip flops and walkovers, etc.”

“I went to Chicago, where my oldest brother (Kendall) was in a show, and I was booked into the Rendezvous Club for six weeks. Joe E. Louis was the M.C. My agent wanted me to go to Florida to another club which was also run by racketeers, but I didn’t want any part of it. I joined a couple of acts, but when my brother Kendall needed a teacher for his dancing school in St. Louis, I grabbed the chance, as I was tired of traveling anyway. I taught for a couple of years and enjoyed it. We had many pupils who became very successful, one by the name of Betty Grable.”

“Earl and my two sisters at this time were doing an act together, and my older sister (Edith) decided to marry a theater manager. So I went with the other two, taking her place. We did very well working mostly vaudeville, some clubs and fairs, on the bill with many big stars – the Duncan Sisters, Three Stooges, Edgar Bergen, etc. We went to Europe where we opened at the Palladium and then played there again after a few weeks in other theaters in London. We opened in a unit in Birmingham, where my (future) wife Marie was one of the Carlton Tiller Girls, a troupe of 16 precision dancers. We worked in that unit together for six weeks, mostly around London. In those six weeks, I was convinced she (Marie) was the one. Just think — I had to go across the ocean to find a girl like Marie, and I thank the Lord for this.”

Edward Walker Capps: 1877 – 1954

Dola Pearl Kyle Capps: 1886 – 1966

Kendall A. Capps: 1903 – 1967

Earl R. Capps: 1905 -1973

Edith Pearl Capps Nevin Minton: 1907 – 1994

Edward Walker Capps Jr: 1909 -1997

Eads Bridget (Bee) Capps McCaskill: 1911 – 1999

Orville Valentine Capps: 1916 – 2005

Dolly Madison Capps Vaughn: 1919 – 2008

Olive Annette Capps Ackerman: 1921 – 2002

Everett (Jimmy) Capps: born in 1924, interviewed for this story

*Story published in 2010.