Lewis Hine caption: George Cox, 13 year old colored boy, has just joined the 4 H Club and is raising a pig. His father is a “renter” in this poor home near the W. Va. Collegiate Institute (Near Charleston) the State colored agricultural college. Mr. A.W. Curtis, Agri. Agent, is helping George. Location: Charleston [vicinity], West Virginia.

“We lived on a hill, in a big white house. Daddy had built steps that went from down near the road up to our house, so we wouldn’t have to walk in the mud.” -Mildred Holmes, daughter of George Cox

African Americans appear in only several dozen photographs that Lewis Hine took for the National Child Labor Committee. Obviously, this was the result of racial discrimination, but not on the part of Hine. Textile mills, factories, and canneries, where Hine took many of his pictures, were almost never integrated. Most mainstream newspapers catered principally to whites, seldom reporting news involving black residents, so almost all newsboys and newsgirls were white. Since there were not very many black-owned farms, most children employed as pickers were white. So Hine seldom encountered African Americans in the fields. As unfortunate as child labor was, it was not a “luxury” available to non-whites, especially among the occupations Hine concentrated on.

In 1921, three years after the bulk of his child labor work was completed, Hine accepted an assignment from the National Child Labor Committee to photograph West Virginia school children, many that were involved in 4-H programs. Early that year, the state had enacted progressive laws limiting child labor and mandating school attendance. Hine’s pictures were supposed to illustrate how those laws were affecting the quality of life for children who otherwise might be typical child laborers.

Institute, where George was photographed, is a small town near Charleston, formed in the 1890s around West Virginia Colored Institute, a black agricultural college. In 1915, the name was changed to West Virginia Collegiate Institute. It is now called West Virginia State University, and was fully integrated in the 1950s, following the historic Brown V. Board of Education decision.

In the photo above, George is getting some guidance from Austin Wingate Curtis, the dean of the college at that time. He was an accomplished educator. His son and daughter, Austin Jr. and Alice, were also photographed by Hine, on the same day. Their stories are also posted on this site.

George Edward Cox was born sometime in 1909, probably in Gladeville, Wise County, Virginia. In 1924, the name of the town was changed to Wise. He was the second of at least seven children born to Philip Henry Sheridan Cox and Estella (Bandy) Cox, both Virginia natives. The family does not appear in the 1910 census, but according to the 1920 census, they still lived in Gladeville, where Sheridan worked as a railroad watchman.

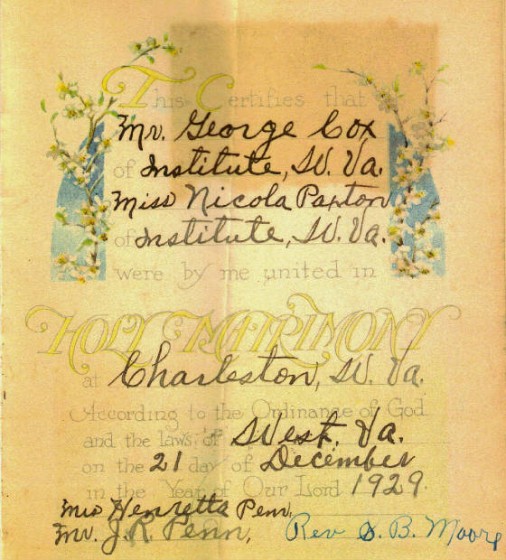

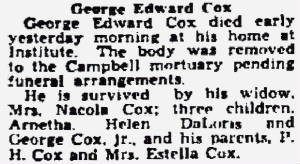

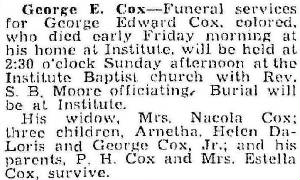

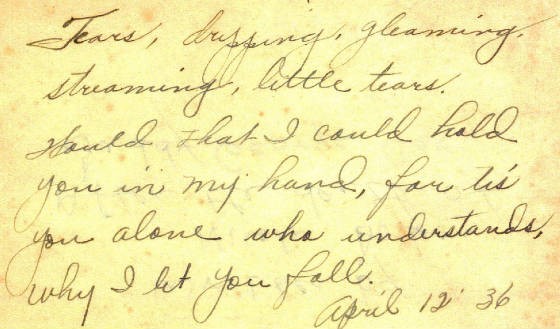

The family moved to Institute sometime in 1920. George Cox married Nicola Paxton in Charleston, on December 21, 1929. He was 20, and she was 15. In the 1930 census, they are listed as living with George’s parents in Institute. George was working as a plasterer. By 1936, He and Nicola had three children. Then tragedy struck. George died suddenly on April 10, after having some teeth pulled the day before.

I located his two surviving children, after finding a 2011 newspaper article about the 100th birthday of George’s sister, Florence. She was not available for an interview. I interviewed George’s daughter, Mildred Arnetha Holmes, and talked to son, George Jr. Both were greatly moved by the photographs of their father.

Lewis Hine caption: George Cox, 13 yr. old colored boy, has just joined the 4 H Club and is raising a pig. His father is a “renter” in this poor home near the W. Va. Collegiate Institute (near Charleston) the state colored agricultural college. Mr. A.W. Curtis, Agri. Agent, is helping George. Location: Charleston [vicinity], West Virginia.

Edited interview with Mildred Holmes (MH), daughter of George Cox. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on November 17, 2011.

MH: I was born in 1930. My father died in 1936, when I was six. He was only 26 years old. He died in Institute. My mother brought me and my sister and brother down to Grandma and Grampa’s house. They were my father’s parents. My grandma opened up the door and we went in, and that’s where my life as I really know it began. My brother and sister remember nothing about my daddy.

JM: How did he die?

MH: I was told that he died of tuberculosis of the stomach. I don’t believe that. My mother told me that Daddy went to Charleston and had some teeth removed. When he came home, he became very ill, and then he died the next day. Many years later, I told my doctor about this, and he asked me, ‘What do you think he died from?’ I said I thought it was septic poisoning, and he agreed.

JM: What was your mother’s name?

MH: Nicola. Her maiden name was Paxton. My father and his brother Cliff, and his father – my grandpa – were plasterers. They were working once in a town I can’t remember the name of (probably Marsh Fork, where she was living in 1920, according to the census). That’s where Daddy met my mother and married her, in 1929, and they settled in Institute. We lived on a hill, in a big white house. Daddy had built steps that went from down near the road up to our house, so we wouldn’t have to walk in the mud.

The house had a well. I remember one day we had a birthday party for my mother. We had ice cream and cake out in the yard. We were singing and getting ready to blow out the candles, and suddenly everyone looked around and said, ‘Where’s Jeff?’ That was my brother George’s nickname. His full name was George Edward Cox Jr. We all began searching for him, and my mother panicked. They went to the well, and my mother found a diaper on top of the well. She hollered and screamed. It was just awful. But there was a big heavy top on the well, so someone said, ‘He can’t be in the well.’ I went down the steps, and when I got down to the bottom, my brother was standing there with not a stitch on, and he was waving at the cars going by. People were laughing and waving back. He was so cute. I snatched him up and ran up the steps and gave him to my mother.

JM: Do you remember anything about what your father was like?

MH: Just that he was very loving to me.

JM: What stories about your father were passed down through the family?

MH: He was a very good plasterer. Some of the buildings in Charleston were ones he had plastered. It was not common for colored people — we call ourselves black now — to have jobs such as plastering. It made them kind of stand out.

JM: Did your mother remarry?

MH: She did much later, to James Dodson. She met him in Charleston.

JM: How did she support the family after your father died?

MH: When Daddy died, she went to Charleston and found a job working for a private family. She lived there. She was off on Thursdays, so she would come down to see us then. It was like a holiday when she came. That went on for years. Grandma and Grandpa raised us. From the day we first walked into their house, we never felt unloved or unwanted. I truly believe that I am the woman I am today because of them.

JM: What were their names, and when did they die?

MH: Grandpa’s name was Philip Sheridan Henry Cox. Grandma’s name was Estella. Bandy was her maiden name. Grandpa died in 1948, and Grandma died in 1964.

I graduated from Teacher Training High School in Institute. In 1946, my mother and her second husband went to Detroit to find a better way of life. The automobile plants were hiring, and that’s where my stepfather worked. In 1947, my mother went back to Institute to get my brother Jeff and my sister Helen. That same year, I married Robert Galloway, and we moved to Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Jeff (George Jr.) graduated from Chadsey High School in Detroit, and then joined the Air Force, and made a career of it. He served in Korea. He retired from the Air Force after 22 years of service, and then attended the University of South Florida, in Tampa, where he obtained a bachelor’s degree. He lives in Tampa now. He never came back to Detroit. He had several children, and all of them were in the military. One of his children, Michael, was just a step away from being a general. Helen also attended Chadsey High School, but did not graduate. She married a Canadian and moved to the Windsor area, just across the bridge from Detroit. She lived there almost her whole life. We used to visit her almost every Saturday. She died about three years ago. My mother died in 2002.

JM: When you were growing up, did you ever live on a farm?

MH: Never.

JM: It looks like your father did, according to the pictures.

MH: Not really. I don’t know where the pictures were taken. That wasn’t at the house my grandpa lived in when I was growing up. Institute was a small village. If you wanted to have pigs and a cow and a garden, you could. It didn’t have to be a farm. That changed over the years. When I went back to visit my grandparents once, they no longer had a cow and pigs. Then one time, I went back, and my grandma made canned biscuits instead of homemade biscuits. I knew at that point that Institute had come into the modern world. It was hard for me to accept.

Institute was always a college town. My grandpa was a plasterer, but he ended up being the head custodian at West Virginia State College. Because of that, students that were going to be teachers did their training in our high school. As a result, the education that we got was a very good one. The majority of the students went to West Virginia State and graduated.

Most of the people that lived in the community worked at the college. When we were in high school, we had a lot of contact with the college. We could go over there. Our physical education programs were held in the college gym. We swam in the college pool. We went to many of the things that happened on the campus, such as the Saturday night movies. I saw Marian Anderson sing there when I was a little girl.

JM: When you were attending those activities at the college, were they fully integrated?

MH: Not at that time. You see, it was a black college. It didn’t become integrated until the desegregation laws were passed. The white people in the surrounding area probably had wanted for so long to send their children to that college. When I was a little girl, there were a lot of white people that lived ‘down the road’ and ‘up the road.’ But they were just people like us.

One of the reasons my ancestors settled in West Virginia was because people in West Virginia did not have the same views on segregation as Virginia had, and it made a distinct difference. We were all just called hillbillies. The first time I saw signs that said ‘colored drinking fountain’ and ‘colored bathrooms’ was when I went to Winston-Salem. It was a shock. I remember looking at my mother-in-law in amazement, and she said, ‘We’ll talk about it when we get home.’ Until my brother went into the military, he had never seen anything like that.

JM: When your father was a boy, do you think he would have also experienced a lack of racism?

MH: No. His life would have been different from mine. But because West Virginia State was a black agricultural college when it was first organized, perhaps Daddy’s life was just as pleasant for him as it was for me.

I live in a senior community here. It’s very nice. One day, a lady was talking about cooking on a wood stove when she was young. She said to me, ‘You remember those days, don’t you?’ And I said I didn’t. She couldn’t believe it. I told her I grew up in a house that had a gas stove. We had hot and cold running water and a washing machine. Our lives in Institute were different, but we didn’t know it at the time.

JM: In one of the photos of your father, he is with Austin Wingate Curtis, who was the dean of the college. His son, Austin Jr., was also photographed by Hine in 1921. He grew up to be a famous scientist and worked with George Washington Carver. He moved to Detroit and established a research laboratory there. Did you know him?

MH: I knew who he was. I saw him from time to time, but I didn’t have any contact with him. Our lives just didn’t cross. I knew that he was in Detroit and worked with Mr. Carver. In fact, my mother worked for Mr. Curtis when she first moved up here to Detroit. I am sure that when she found out that his laboratory was here, she sought him out. She didn’t want to work in a private home anymore. I don’t know how long she worked for him. She ended up working for the Detroit school system.

JM: Do you remember anything else about your father?

MH: I remember a story my Grandpa told. When my Daddy and his brother Cliff were plasterers, a lot of their friends had gone to work in coal mines in northern West Virginia. One day, Daddy and Uncle Cliff told Grandpa that they wanted to do that, too. So against Grandpa’s wishes, they went up there to look for work, and they got hired. On the first day, the company put them down in the pits. When it got to be lunch time, they opened up their lunch boxes, and Uncle Cliff said, ‘Be quiet, what is that noise?’ And Daddy said, ‘It sounds like a woman screaming.’ They looked at one another, closed up their lunch boxes, and pulled a rope that signaled that you wanted to leave the mine. When they got out, they quit right then and there.

I remember one more thing about my daddy. Back in Institute, an orange was a very rare piece of fruit. We had plenty of apples and pears and plums and strawberries and peaches. They grew all over the place. One day, Daddy gave me an orange. It was like a gift from heaven.

“I was totally delighted and thrilled to see the pictures of my father. I was only two years old when he died, and I don’t really remember him. My mother was always praising him and telling me and my sisters how much she loved him and how much she missed him. I have one tiny photograph of him. I had carried it in my wallet for the last 20 or 30 years. But just about a week ago, I took it out of my wallet and slid it into the frame where my mother’s picture is. I placed it right by her heart.” -George Cox Jr.

*Story published in 2012.