Lewis Hine caption: Some of the younger workers (not all) who work in the Biloxi Canning Factory. On right-hand end of photo is Lazro Boney, 12 years old, been working 4 years at this factory. Both he and his mother said he makes $1.75 a day when shrimp are large and plentiful. He made $57.00 last year in 3 months. His brother Ed (not in photo) 14 years old, makes $2.25 on good days. Another brother, Pete, (one of the smallest in the photo) and 10 years old makes 50 cents a day. Two other brothers work at raw oysters; one, 17 years old, makes $4.00 a day. Eight ch[ildre]n in family. The mother said, “Lazro goes to school when he ain’t workin; but he’s gettin’ so he’d rather stay home with the boys than go to school.” Family lives at 616 Charter St. Next to Lazro (in photo) is Jim Kriss, 11 years old, been working at this factory two years; makes $1.50 on good days. His brother Jo Kriss (in photo next to girl on left end) 12 years old, makes $1.00 a day. Another brother Ed, not in photo, 14 years averages $2.50 a day. Sister Marie 7 years old (see photo at home) works when not tending the baby, and makes 25 cents a day. Mother picks also. Youngest boy in photo is Tommy Davis, 8 years old. 918 Charter St. Worked last year. Ester Barton, a 12 year old boy also is the photo, couldn’t spell his own name. Been working two years. “Teeny” Adams, girl on left end of photo, 11 years old, makes $1.15 some days. Missed three weeks of school last month, working. Works now before school, or all day. See also summary of young workers I found (on other label). Location: Biloxi, Mississippi, February 1911.

“I make it to Biloxi some three or four times a year, and I don’t think there’s ever a trip over there that someone doesn’t comment on my grandfather. They remember him walking around the neighborhood, and how friendly he always was.” -James Boney, grandson of Lazaro Boney

From The American Child, National Child Labor Committee (1922):

Mr. Henry F. Pringle, Staff Correspondent of the New York World, has made a bad mess of things. He has been writing a series of articles describing the conditions of working children in different parts of the country, and has fallen afoul of the Chamber of Commerce of Biloxi, Miss.

In the course of his studies Mr. Pringle visited Biloxi to see the little children at work in the oyster and shrimp-canning sheds. His description is graphic and convincing, but unfortunately he chanced to land in the town during a few days of sub-normal weather and spoke of it. When Mr. Pringle slandered Biloxi by saying that in many days of early November, “there is no sunshine at all and the air is far from balmy, with rain driving in from the gulf and the wind moaning through the palm trees that fringe the shore,” he was headed for destruction.

Now it happens that the Biloxi Chamber of Commerce has been boasting “the genial southern sunshine” and the “balmy atmosphere,” and they are very much peeved because the effect of Mr. Pringle’s articles may be detrimental to Biloxi’s major industry, entertaining northern tourists. “We do not care what you say about child labor in our nasty canneries, Mr. Pringle,” the Chamber of Commerce seems to say, “but lay off our climate, for climate is vital to our beautiful hotels, our magic Gulf-shore drives and our verdant golf links.”

In describing the work of children in Gulf Coast shrimp canneries, Mr. Pringle has stumbled again. He speaks of the injury to the children’s fingers from a “thorn” in the head of the shrimp which often causes festering sores, and adds, “There is an acid in the shrimp, also, which eats the little fingers.”

Let us rise to correct Mr. Pringle before it is too late.

Some ten years ago when the National Child Labor Committee was studying child labor conditions in Gulf Coast canneries, we made a statement similar to this and the very day a prominent Gulf Coast canner came in to our office to tell us how many different kinds of a liar we were, a bulletin came from the Federal Government explaining that those who can shrimp in tins should have the tins lined according to Government specifications, because the shrimp secretes an alkali that not only eats into the flesh of workers and destroys shoe leather, but actually eats tin.

Of course the people who work in the canneries and the people in the community always speak of it as an acid, and they may be forgiven, but neither the New York World nor the National Child Labor Committee can afford to make such a mistake. It is not an acid, Mr. Pringle, it is an alkali.

**************************

The following was based on an 1895 interview with Charles Patten, manager of the Biloxi Canning Company. The interview was conducted by Charles L. Dyer, for his book, Along the Gulf, published in 1895 by L&N Railroad:

The Biloxi Canning Company was started in 1881 and from a small beginning the plant has been gradually built up, until at the present time it occupies a space of 100 feet by 500 feet, running from the street to the end of the wharf where vessels land. They employ during the busy season about 350 hands and their goods are shipped to all parts of this country and Europe. England is one of their best customers and indeed it would seem so, for on the day that our party visited the cannery a shipment of 525 cases of canned shrimp was sent to a London firm. This company, as a matter of course, cans oysters and shrimp, and they also ship raw oysters away in bulk. In addition to this they have made quite a specialty of canning figs.

Regarding the shrimp, which are put up in cans, two dozen of which go to the case, the Biloxi Canning Company has made a departure in the line of packing. It is a well-known fact that if the shrimp touches the tin of the can it immediately loses its bright red color and becomes black and unsightly. To obviate this, the other companies use a muslin bag, in which the shrimp are placed before being packed. Now, instead of this muslin bag, in which, according to Mr. Patten, the shrimp are liable to get broken up slightly in filling the bag the Biloxi Canning Company have substituted a wooden veneer lining, which, while it completely prevents the shrimp from touching the tin, at the same time absorbs what little moisture there is in them when they are packed and renders them perfectly dry and palatable as they are intended to be when placed upon the table.

All of the canned goods of this company are put up under a distinctive mark of their own called the “Cotton Bale Brand,” which is favorably known wherever the goods have been seen. The present officers of the company are W.A. Gordon, president; Charles E. Theobald, vice-president; C.F. Theobald, secretary and treasurer; Charles Patten, manager.

Lewis Hine caption: Some of the shrimp-pickers working at the Biloxi Canning Co. Within an hour I obtained the following names, and photos taken at the factory, and at home, all working here: Two Children of five years. One of seven years. Two of eight years. One of nine. Two of ten. Two of eleven (one had been working at this factory two years). Three of twelve, (one working here 4 years and one two years). I do not believe this is a complete list of the youngsters. Location: Biloxi, Mississippi, February 1911.

Lazaro Boney was not hard to find, given his unusual and colorful name. Shortly after I started my research, I tracked down his grandson, James Boney, who had already seen the photographs. But he was surprised to learn of their historical significance, and that I was exploring his family history.

As it says in the caption of the first photograph, 12-year-old Lazaro had “been working 4 years at this factory.” As had been reported many times by the National Child Labor Committee, some of the youngest child laborers worked in the canneries, along the Gulf Coast, in South Carolina, and in Eastport, Maine. Many of the southern cannery workers migrated from Baltimore, Maryland in the winter. Most of them were Polish or Bohemian immigrants, who returned to Baltimore in the spring and summer to pick fruits and vegetables on farms in the rural counties around the city. But Lazaro was not from one of these families.

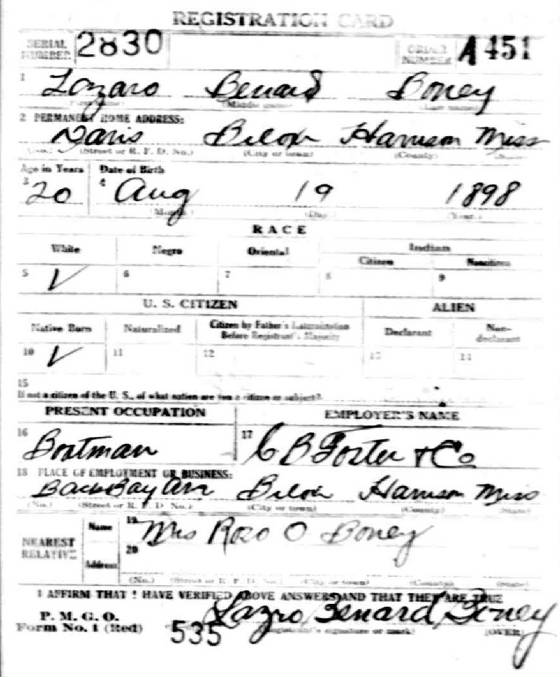

Lazaro Richard Boney was born in the Biloxi area on August 9 (or 19), 1898. Some records indicate that his middle name was Bernard. He was the sixth of 10 children born to John and Rosa Boney, both Mississippi natives, who married about 1892. John’s parents were born in France. John was an oysterman, and probably worked on the oyster boats, since the shucking and canning jobs were filled mostly by women and children. In the 1920 census, Lazaro is listed as an oyster fisherman, and he is living with his parents in the home that they owned at 969 Main Street, right on the coast of Biloxi. The site is now occupied by a parking lot near the Boomtown Casino. The area was devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

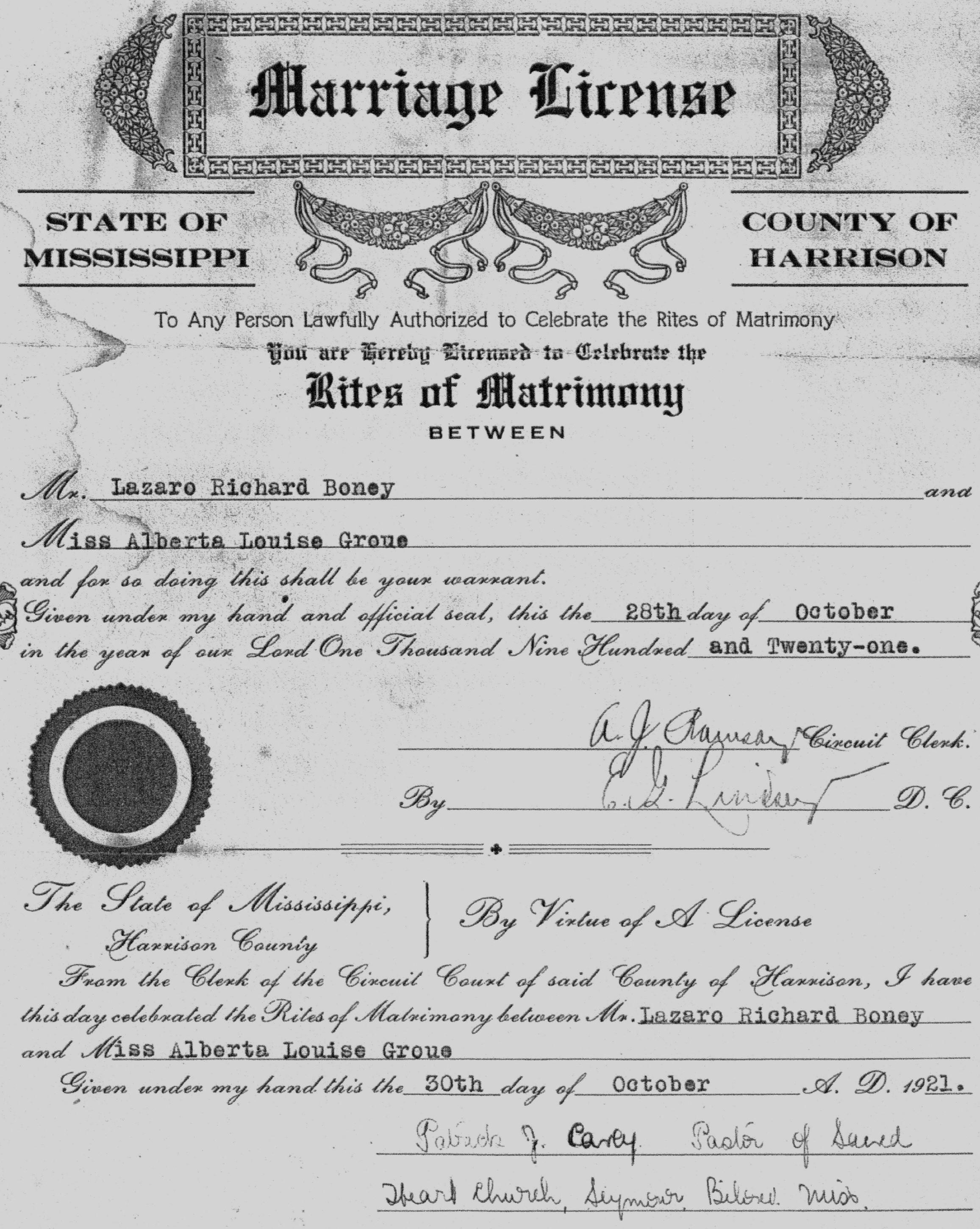

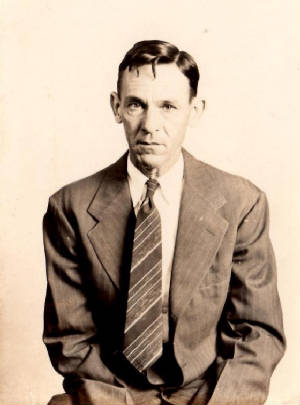

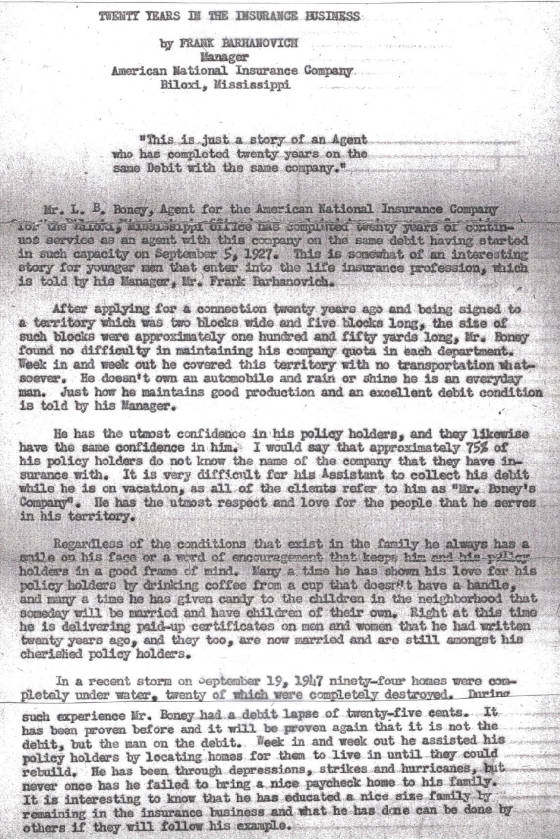

Lazaro married Alberta (Bertha) Louise Groue (or Grou) in Biloxi on October 30, 1921. They had two children, a boy and a girl, and one stillborn child. Their son, Elwood, was the father of James Boney, who I interviewed for this story. Lazaro worked much of his life as an insurance agent and was remarkably successful, despite having to travel on foot for his entire sales route. See his commendation letter at the end of this story.

He passed away in September of 1970, at the age of 72. Bertha passed away in 1989. Peter Boney, Lazaro’s brother, who also in appeared in the Hine photos, died in Baltimore in 1968.

Edited interview with James Boney, grandson of Lazaro Boney. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on January 6, 2011. Transcribed by Celeste Ramsey and edited by Manning.

JM: When did you first see the child labor photo of your grandfather?

James: My brother sent it to me about two or three years ago. It was a shock because I did not realize my grandfather was even in the shrimp or fishing industry. I knew that some of his brothers were. In fact, they were in the fishing industry all their lives. But I did not realize that my grandfather started out that way.

JM: It says in the caption that he’d been working there four years. How do you feel about that?

James: My mother’s father was in the oyster business in Biloxi, and my mother told me that when she was four years old, she was separating shrimp and packing oysters, so I am not surprised.

JM: What year were you born?

James: 1948.

JM: So you knew your grandfather about 22 years. Did you always live close to him?

James: Very close, within a mile and a half.

JM: What do you remember about him?

James: He was an insurance salesman. He didn’t own a car. His district was in the eastern side of Biloxi, which was probably about a three-mile walk, which he would walk every day. And he always walked in a suit. Every weekend the family would get together for Sunday lunch. We’d all go to Mass, and then get together and have fried chicken or fried fish or whatever. We’d play checkers in the afternoon.

JM: What kind of a checker player was he?

James: He was good.

JM: Did you ever beat him?

James: Oh, I don’t remember, but I know I had fun playing with him.

JM: When you were with him, what would you talk about?

James: We would mainly talk about me, you know, about how I was doing in school, and about my friends. When I was in elementary school and junior high, I would spend the night with my grandfather and grandmother a lot. So in addition to the Sunday get-togethers, I was with them quite a bit during the week and at night.

JM: Do you know how he got into the insurance business?

James: No, I don’t.

JM: Did he own his home when you were growing up?

James: Yes.

JM: What kind of house was it?

James: It was a one-story rectangular building, about 40 feet wide and 60 sixty feet deep, and it had a big screened porch. It was the second home that he and my grandmother had lived in. The house is still standing today.

JM: When did he retire?

James: He retired in the mid-to-late sixties, only a couple years before he died of congestive heart failure.

JM: What was his wife’s name?

James: Bertha Grou, or possibly Groue.

JM: That sounds like a French name.

James: Correct. So is Boney.

JM: Was it Bonet or something like that before?

James: Yes. Most of the names were changed in baptismal and confirmation records. It depended on how the priest interpreted the name. I’ve seen it spelled Boni.

JM: Was he called Lazaro, or was there a nickname?

James: He always went by Laz.

JM: What was your grandmother like?

James: She was a wonderful woman.

JM: Did she work outside of the home?

James: No. She was a homemaker as long as I knew her.

JM: How many children did they have?

James: They had two that lived, my father and my aunt, and one that was stillborn.

JM: What did your father, Elwood, do for a living?

James: When he came out of the Navy, he was a shrimper. He worked on a shrimp boat and would be gone for a week in the Gulf and then home for a week. And when I was probably four or five, he went into the construction business. When he retired, he was a construction superintendent, primarily building houses.

JM: Did your father graduate from high school?

James: Yes.

JM: What do you do for a living?

James: I’m a CPA. I was comptroller for a company in Houston called Transco. I retired from there in 1993. I went to work for an outsourcing company for five years, and then I opened my own business in 1999.

JM: Where did you get your accounting degree?

James: The University of Southern Mississippi. I paid my own way. With my mom and dad having seven kids, there was no way they could afford it. So I saved money through high school, and then worked through college; and then I got a student loan and went through ROTC and received a commission into the Army when I graduated.

JM: What did your grandfather Lazaro like to do when he wasn’t working?

James: Drink Falstaff beer and play checkers. On his way home from work, he would buy two of the tall cans of Falstaff and come home and sit at the kitchen table and drink them.

JM: What do you miss about him most?

James: His smile. He had one really big smile. That I’ll always remember.

JM: Do you think he was comfortable and happy with his life?

James: I do; and I say that because of the people that I talk with today. I make it to Biloxi some three or four times a year, and I don’t think there’s ever a trip over there that someone doesn’t comment on my grandfather. They remember him walking around the neighborhood, and how friendly he always was. His family was very important to him. I remember that he had a stroke, and I was at the house when it happened. Both my dad and I were there. I remember him lying on the floor and the ambulance coming to get him. He survived that, and went on for many years after that. I remember him and my grandmother were always together when he wasn’t working. They truly loved each other.

Lazaro Boney: 1898 – 1970

*Story published in 2011.