Lewis Hine caption: Six-year old boy, Louis Shuman, and his 11 year old brother. Dallas Newsboys. The little fellow usually has a brother who makes him do most of the work. Dallas has too many of these little newsies. Location: Dallas, Texas, October 1913.

“When I was studying about the Great Depression in school, I asked him (Louis Shuman) if he was hurt by that. He just said that he always had money and always had a job. He was apparently the breadwinner for the whole family for a while. He told me that in the 1930s, he worked in the water mines, in the Cabazon area, near Palm Springs. They were bringing the water to Los Angeles.” -Joseph Bloom, son of Louis Shuman

“Morris was called Mike. Mike was kind of an entrepreneur. His owned some auto repair shops. During the war, my father (Moses Shuman) invented a sorting machine. It sorted the nuts and bolts that fell on the floors of factories. People could pick them up and throw them into the machine, and they came out sorted and cleaned. Mike worked with my father on that. After the war, Mike retired, and then he died of a heart attack. Most of his brothers died young, all from heart attacks. Louis was a really good guy. He was sociable, he was lovable, and he cared about people.” -Norman Shuman, nephew of Morris and Louis Shuman

According to David J. Wishart, author of Encyclopedia of the Great Plains (2004), more than a million Jews left Russia and other European countries between 1880 and 1914, and settled in the United States. Many came to the Great Plains states either from east to west through Canada, or north from Galveston, Texas. Most made a living as peddlers, whose customers were homesteaders and Native Americans. They made their homes in rural towns, and established dry goods stores and grocery stores, or operated scrap metal businesses along the railroad lines. They eventually migrated to cities such as Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska. Among those families were the Shumans.

Lewis Hine was a man on a mission, and probably a man in a hurry as well. In the last several months of 1913, he traveled all over the Gulf States in search of child laborers, on farms, at seafood canneries, in cotton mills, and on the streets of cities such as Dallas. His large box camera was cumbersome, certainly by today’s standards. It took him a while to set it up, and he probably had only a minute or two to capture the image before the children would become restless, or he was chased away by suspicious employers.

He often knelt down in order to photograph children at eye level, knowing full well that this view would elicit more sympathy. That was certainly the case here. His focus was on young Louis, barefoot and looking very much like the proverbial street urchin. That is why Morris is leaning over; otherwise, his head would have been out of view. Hine makes a cameo appearance of sorts (note his shadow). If Hine had been afforded the opportunity to pry more information out of the Shuman brothers, he might have discovered that they had one thing in common with him — they were well traveled, but for vastly different reasons.

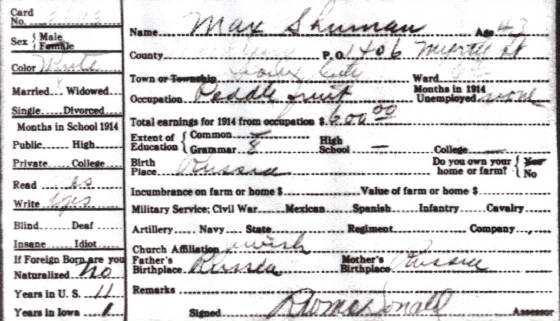

In 1913, Louis and Morris had been in the US seven years. Although I could not locate the family in immigration records, other records indicate that their father, Max, first came over in 1904, and then he returned to Russia and brought back his family in 1907, when Louis was only one year old. In 1910, Max, wife Rebecca (Weinstein), and four children, Morris, Rose, Sophia, and Louis, lived at 2324 N Street, in Lincoln, Nebraska, according to the census. Max worked as a junk peddler.

By 1913, they were in Dallas, as we know from the photograph; but a year later, they had moved north to 1406 Myrtle Street, Sioux City, Iowa, according to the 1915 Iowa Census. Max was a fruit peddler, and they had two more children: Moses, born in Colorado in November of 1910, and Solomon, born in Nebraska in 1913. But in 1920, the census lists them back in Dallas, where they rented an apartment at 2213 Alamo St, the present location of several large parking lots in downtown Dallas, according to Google Maps. Max was a junk peddler again, and 19-year-old Morris was working as an auto mechanic. They had two more children, Freida and Sarah, born in Colorado in 1917 and 1918.

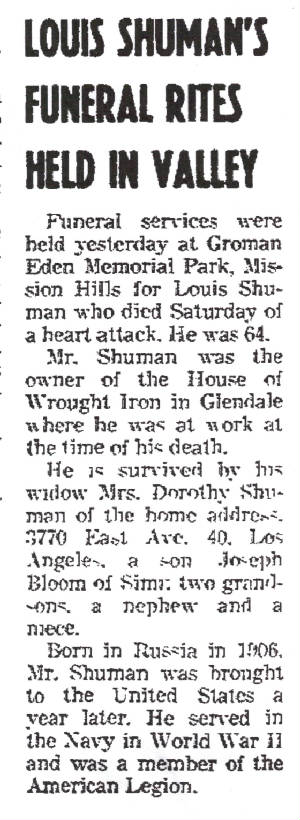

By 1930, the family had headed west to Los Angeles, where they owned a home at 2601 Brooklyn Street. The census reported that Max was no longer working, but that Morris and Louis were auto mechanics. Per official death records, Max died on January 10, 1940; wife Rebecca died on August 6, 1962; Moses died on November 22, 1948; Morris died on August 11, 1955; and Louis died on November 28, 1970. All died in Los Angeles except Rebecca, who died in Galveston, Texas, where one of her daughters lived.

According to his obituary, Louis was survived by his wife, Dorothy, and son, Joseph Bloom. After much effort, I contacted Mr. Bloom, who had never seen the photo. He told me that his mother and father divorced when he was a boy, and when his mother remarried, he took the last name of his stepfather. That explains why his name is Bloom, not Shuman. But he was very close to his father, as we will learn from my interview with him.

Edited interview with Joseph Bloom, son Louis Shuman. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) in July 2010.

JM: When were you born?

Bloom: On February 14, 1943, in Long Beach, California.

JM: Why is your name Bloom, and your father’s name is Shuman?

Bloom: My mother and father divorced, and when she remarried, I took my stepfather’s last name. My original name was Mendel Shuman. You learn how to fight real quick when you have a name like that. My middle name was Joseph, so I changed it to just Joseph.

JM: When you were born, where were your parents living?

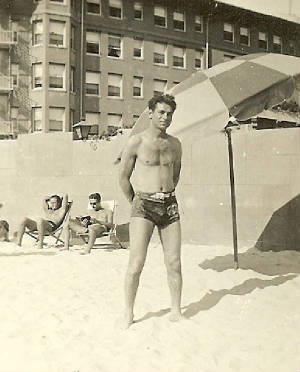

Bloom: My dad was in the Navy. He was on a crash rescue boat, which is kind of like a PT boat. He was all over the place during the war (World War II), but always stateside, mostly in Texas and California. We moved to wherever he was.

JM: When did your parents marry?

Bloom: In 1941.

JM: Did they have any other children?

Bloom: No.

JM: Did your mother work?

Bloom: Yes, but after they divorced. That was about 1952.

JM: How did that change your relationship with your father?

Bloom: I was even closer to him. I got to spend every weekend with him. He didn’t have a lot of money. He was just a body and fender mechanic after the war. The most fun I had with him was when we just went out and did nothing. We would go to the Sears tool department on Friday nights.

JM: Mechanics love places like that.

Bloom: I did, too. He had a brother named Paul, who had a phenomenal garage that had all kinds of tools. His name was really Solomon, or Saul, but he was called Paul. Lou and I would do anything that was cheap. We’d go to old movies. We had about as close a relationship as you can have. Lou also liked to watch old trucker movies. The other boy in the picture, Morris, was called Mike. He died the earliest of the kids. Lou worked for Mike. He drove an old truck hauler across the country, picked up old cars, and brought them back for Mike.

JM: You called him Lou?

Bloom: He was always Lou to me.

JM: Did Lou remarry?

Bloom: He married Dorothy in 1962. I didn’t know her very well.

JM: Did he talk to you much about his younger days?

Bloom: When I was studying about the Great Depression in school, I asked him if he was hurt by that. He just said that he always had money and always had a job. He was apparently the breadwinner for the whole family for a while. He told me that in the 1930s, he worked in the water mines, in the Cabazon area, near Palm Springs. They were bringing the water to Los Angeles. I imagine that he was a mechanic rather than a driller. And then he worked at a chocolate factory for a while, also in California. He used to talk about rats falling into the vats of chocolate. In the 1930s, he and Mike got a patent for making the first self-adjusting brake.

JM: They did this for an employer?

Bloom: No, on their own. Studebaker eventually got the patent. Those brakes are on every car in the world now. They could have been millionaires many times over, but they never made any money from it. They didn’t have the money to renew the patent, so Studebaker just waited for it to expire. After the war, they invented a machine that made the kind of concrete block bricks that have two holes in the vertical portion. They never got a dime out of it.

JM: Did he try to sell it to big companies?

Bloom: They didn’t know how. In the late 1950s, we went to Sears one time, and he turned ashen. I asked him what the matter was. He had seen a socket wrench, with a little magnet that fits inside it with a circular halo. It was made out of plastic. Lou also invented that, and he had given it to a patent attorney, who apparently swindled him. He looked at me and said, ‘I will never invent anything again.’

JM: Was he bitter about it?

Bloom: No.

JM: Did he ever invent anything again?

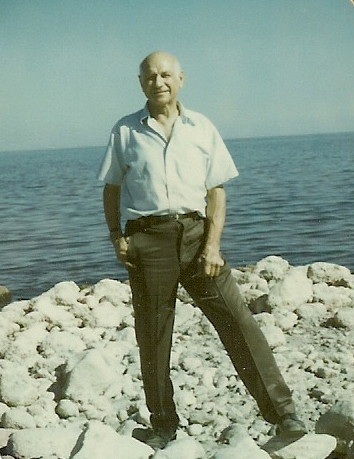

Bloom: Oh sure. He always made stuff. In his last years, he got tired of mechanics, and also got tired of punching a clock. So he opened up a secondhand antique and wrought iron manufacturing company, a one-man operation. He did everything by hand. Just before he passed away, he got a contract with Busch Gardens to fabricate all the parrot cages for their entire facility.

JM: He must have made some money from that.

Bloom: He might have made a little. But he always lived a meager existence.

JM: What kind of houses did he live in?

Bloom: When I was growing up, we lived in rentals. He lived upstairs in his shop for a while when he had the shop, before he married his second wife Dorothy. After they married, they rented an apartment.

JM: In 1948, he was living at 2143½ Brooklyn Avenue, according to the LA city directory.

Bloom: Right. My grandmother lived at 2161. She was Lou’s mother. I remember that we used to walk to her house a lot. She made cherry wine, and we’d always come back with some of that.

JM: In 1954, your father is listed as no longer married, and he’s living at 3137 Perlita Avenue.

Bloom: I know where that is. It was a little single-family residence. It was right next to Glendale. It’s gone now. I went by there one day, and I remembered that we had frogs. We went down to the LA River and caught a bunch of tadpoles and brought them back and raised them.

JM: In the 1910 census, your father is listed as living in Lancaster, Nebraska. They are Yiddish-Russian. Max’s wife is named Rebecca, and they married about 1898. He’s a junk peddler. They have four children, Morris, Rose, Sophia and your father. In the 1915 Iowa census, the family lived in Sioux City. Your grandfather was a fruit peddler. In the 1920 census, they are back in Dallas. They had seven kids with them at the time, Morris, Sonya, Louis, Moses, Solomon, Frieda and Sarah. The last four were born in Colorado.

Bloom: Sophia was Sonya. I don’t know anything about her. I saw Rose about 10 years ago, shortly before she died. We talked for a few hours. She wound up in Galveston. She met a football player, and she said he was the most handsome man she ever met. They got married and stayed in Galveston. Frieda wound up in Hollywood. She was called Fritzy. She was a very successful hairdresser. She did Ava Gardner’s hair, Lucille Ball’s hair and Barbra Streisand’s hair.

JM: There are no other records of them in Dallas, except the Hine photo. So we know that they were in Dallas in 1913, and after going to Iowa and Colorado, they returned to Dallas. There was a wave of Russian Jews who came to Colorado and surrounding states. Most of them spoke German. They were called Volga Deutsch, because they were from the Volga area of Russia, but they spoke German.

Bloom: They were German. Their name in Russia was Shictkman, but they changed it to Shuman. My family was thrown out of Germany in the 1870s. Catherine the Great offered the Jews land in Russia, but then the family was thrown out of Russia in the early 1900s by the pogroms (large-scale attacks on Jews). My grandfather was a rabbi in Russia, and he also served in the Russian Army. As I understand it, my grandfather once knocked out the commanding general of the Siberian Army because he made a pass at my grandmother.

I think my grandfather came over a couple of times, and that he had money at the time. When he came over on the boat from Russia, he met a guy, and they became good friends during the trip over. He wanted my grandfather to be a partner in a cosmetics business he was starting. My grandfather told him, ‘I don’t see why anyone would use rice flour on their faces.’ The guy’s name was Max Factor. The family was in Philadelphia for a short time. While they were there, they had a baby son who reached for a pot of hot milk and it scalded him to death.

JM: What else can you tell me about Lou?

Bloom: He was a writer and composer also.

JM: So he was a musician?

Bloom: No, he never played any instruments. The songs just came out of his head. He wrote down the words, and he just sang them. There was one he wrote in the mid-1960s. He was very much a patriot. It was during all the anti-war stuff. It was called ‘Strike Up the Band.’

JM: The Gershwins wrote a song with the same title.

Bloom: This was different. I have a whole book of his writings. I still cry when I see the stuff.

JM: When did your mother die?

Bloom: About two years ago. She was 88.

JM: What kind of relationship did she have with your father after the divorce?

Bloom: They talked every once in a while, but that’s about all.

JM: Your father fled Russia with his parents when he was a little boy. They moved from Nebraska to Colorado to Texas to Iowa to Colorado to Texas and finally to California. It must have been an incredible struggle. Did your father ever talk about that?

Bloom: He never mentioned it. He never complained about anything. He was the most positive person you could ever meet. He’d always have a smile on his face and a joke to tell you. He was the most giving man I’ve ever met. He didn’t have much himself, but whatever he had, he would share with anybody. Lou loved to recite poetry. There’s a man named Robert Service. He was in the Yukon at the turn of the century. Lou knew one of his poems verbatim, ‘The Cremation of Sam McGee.’ He taught it to me when I was eight years old. He loved those ballad poems about men overcome big obstacles. Maybe that’s because he did the same thing in his life. As far as religion is concerned, he was not a traditional Orthodox Jew. He had his own relationship with God, a one-on-one relationship. He also wrote some poems. In one of them, he wrote, ‘I’m not a God-fearing man, I’m a God-loving man.’ I want to give my dad his due. Here’s a man that never made it to greatness, but he had a helluva lot to offer.

Louis Shuman: January 6, 1906 – November 28, 1970

Morris Shuman: May 20, 1901 – August 11, 1955

*Story published in 2010.