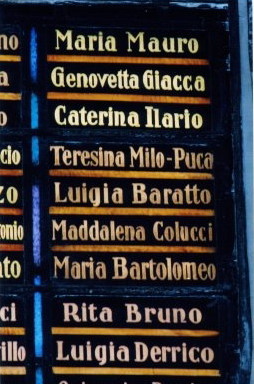

Lewis Hine caption: 5 P.M. Mrs. Mary Mauro, 309 E. 110th St., 2nd floor. Family work on feathers. Make $2.25 a week. In vacation 2 or 3 times as much. Victoria, 8 yrs. Angelina 10 yrs. (a neighbor). Frorandi 10 yrs. Maggie 11 yrs. All work except two boys against wall. Father is street cleaner and has steady job. Girls work until 7 or 8 P.M. Once Maggie (11 yrs.) worked until 10 P.M. Location: New York, New York (State), December 1911.

(Clockwise starting with mother): Mary, Victoria, Angelina (a neighbor), Fioravanti (Fiore), Antonio (Anthony), with arm around sleeping brother Giovanni (John), and Domenica (Maggie). Girl sitting behind mother was Jessamina (Jessie). The photo on the wall is of King Umberto I and his family, and that’s a calendar hanging near the door.

“When I was growing up, my father told me stories about how poor they were. But when you’re a kid, it doesn’t make much of an impression on you. But looking at this photograph, it’s heartbreaking to see that the children had to work, and to see the condition of that room. It was a wake-up call to witness how my family started out in America, and how hard their life must have been.” -Margaret Mauro, daughter of John Mauro

The following are excerpts from State of New York, Preliminary Report of the Factory Investigating Commission, Volume 1, transmitted to the Legislature on March 1, 1912.

In 1904 there were 2,604 tenement houses in the city of New York licensed for manufacturing. In November, 1911, there were 13,268 licensed tenements in that city, and 451 in the remainder of the State. In considering the number of tenement houses in which manufacturing is actually carried on in the city of New York the following facts should be borne in mind:

1. Each of the 13,268 licensed tenements contains anywhere from three to forty or fifty different apartments in which manufacturing may be carried on.

2. The 13,268 licensed tenements represent those only in which the manufacture or preparation of the forty-one articles specified in section 100 of the Labor Law is carried on. Testimony showed that at least one hundred different articles are in process of manufacture in tenement houses in the city of New York. The preparation or manufacture of almost sixty articles requires no license and may, therefore, be carried on practically without any supervision save that incidentally exercised by the Tenement House and the Board of Health.

This investigation showed that the provisions of the law requiring a license for the manufacturing of the articles specified are violated in many cases. Accurate lists of home workers are not kept by the manufacturers as the law requires.

Under the present system, with the force at the disposal of the State Department of Labor for this purpose, the enforcement of the law relating to home work is a hopeless task. Increase in the number of inspectors will help but little.

Miss Watson of the Child Labor Committee testified to the following case of a child suffering from scarlet fever engaged in home work:

“I have seen a girl in the desquamating stage of scarlet fever (when her throat was so bad that she could not speak above a whisper) tying ostrich feathers in the Italian district. These feathers were being made for one of the biggest feather factories in the lower part of the city. She told me herself she had been sick with scarlet fever for ten days, but had been upstairs in a neighbor’s room working for over a week. The condition of the skin on her hands was such as to attract my attention and be recognized at once as scarlet fever, although she further authenticated it by telling me the doctor stated she had scarlet fever.”

Unfortunately the law does not adequately guard against this, presumably because the diseases are not reported to the Board of Health or to the Labor Department as promptly as they should be, and in some cases are not reported at all.

**************************

From December 1911 through February 1912, Lewis Hine took about 120 photos of immigrant children doing piece work at home for various food processing companies, and garment, flower, and feather factories. It was a hotly debated subject in the city at the time, and the National Child Labor Committee wanted to build a case against the practice. A hundred years later, these photos of immigrant families, many of them Italian, have become a valuable resource for the study of immigration, and for families searching for ancestors.

This is one of the few stories I have done where I did not choose a photo and search for descendants. A descendant contacted me instead. In the early summer of 2012, I received the following email.

“My name is Margaret Mauro, and some years ago I visited the Ellis Island Museum, and I discovered a photo of my family taken by Lewis Hine. The discovery was purely accidental, but was confirmed when I realized the address and date of the photo coincided with our family history. My grandmother is at the table assembling ‘feathered goods’ along with my aunts and my Uncle Fiore. In the photo are two other boys, an older son holding the younger on his lap. The small child on his lap was my father.”

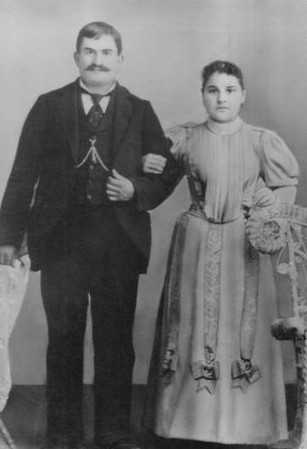

I found the Mauros in the census, and learned that father Giuseppe (Joseph) and mother Portia Maria (Mary) came to the US separately from Italy in the early 1890s, were married in 1895, and were both naturalized in 1897. In the 1910 census, Mary stated that she had given birth to 10 children, but only six had survived. They had one more in 1912. I interviewed Margaret Mauro, and she will tell us the rest of the story.

It is interesting to note that in her interview, we learn that two of the Mauro children had rheumatic heart disease, often caused by scarlet fever, which was cited in the above 1912 report by the Factory Investigating Commission (“I have seen a girl in the desquamating stage of scarlet fever when her throat was so bad that she could not speak above a whisper tying ostrich feathers in the Italian district.”).

*Except where noted, all photos provided by Margaret Mauro.

Edited interview with Margaret Mauro (MM), granddaughter of Mary Mauro, and daughter of Giovanni (John) Mauro. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on July 19, 2012.

JM: When did you first see the Lewis Hine photograph?

MM: About 1994. I was visiting the Ellis Island Immigration Museum in New York. It was getting toward the end of the day, and I went into a room called ‘At Work in America,’ and the picture was hanging there. The rest of my family hadn’t caught up with me. I was trying to hurry them through because the last ferry of the day was going back soon. I stared at the picture, and then I read the caption, and it said, ‘The Mauro Family,’ and of course, that’s my name. But none of the individual names were mentioned. The address was also in the caption, 309 East 110th Street, and that was where my grandparents were living when my father was a boy. They lived in Harlem.

My family finally caught up with me, and we went to the book shop. I took a book off the shelf, opened it up to a random page, and to my surprise, there was the picture. The caption mentioned some of the first names, and they were the names of some of my aunts and uncles. I knew then that the little boy sleeping had to be my father, and his brother Tony was holding him. A while after, my brother and I took a trip to the Library of Congress and looked up other Lewis Hine photographs, thinking maybe he took another one of my family, but we didn’t find any.

JM: Did you tell any of the Ellis Island staff that it was your family in the photograph?

MM: I sent them an email about it later, but they never replied.

JM: What do you think about the situation your family was in then?

MM: When I was growing up, my father told me stories about how poor they were. But when you’re a kid, it doesn’t make much of an impression on you. But looking at this photograph, it’s heartbreaking to see that the children had to work, and to see the condition of that room. It was a wake-up call to witness how my family started out in America, and how hard their life must have been.

JM: Did you know your grandmother, the one in the picture? And did you know your grandfather?

MM: No. She died before I was born. She came here as Portia or Borzia, then she became just Portia, and then Mary and Maria. She was trying on all these names. She married my grandfather in New York. I knew him. He died in 1956, at age 83. I remember visiting him in his apartment in Harlem.

JM: What did your father tell you about his life while he was growing up?

MM: He was always trying to tell us how fortunate we were, because he had so little. He told me that he would stand in the street and scream and scream for a penny, and he wouldn’t get it. The brother who had his arm around him, Antonio, called Tony, was his buddy and protector. My father died from Alzheimer’s. When I would visit him, he would always ask, ‘Where’s Tony?’ He kept asking for him, but he had long since died.

He told me his mother was really tough, that she was almost feared in the neighborhood. She was known for her physical strength. My grandfather was like the old Italian guy who sits out in front in his white suit on Sundays, while she lugs the trash cans around. They were the superintendents in the building. She was very protective of her family. My Uncle Tony, who was a police officer, was threatened one time by some people who were probably mixed up in organized crime. The story is that she went into a bar where these people were. They were playing pool, and she broke some pool cues and threatened them. Tony was embarrassed.

JM: When did your father and mother marry?

MM: In 1934. My mother’s name was Georgina Mazza.

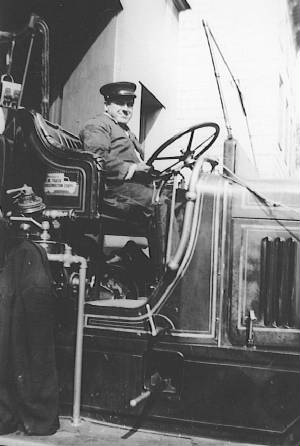

JM: What was your father doing for a living at that time?

MM: He was a New York City firefighter. He was one of the first Italian Americans to become a firefighter. It was very Irish at that time. He started that job in 1933. Before that, he drove a truck for Gimbels, the department store.

JM: Where did your parents live when they first married?

MM: I think they lived in the Lower East Side at first, probably 14th Street. And then they moved to the Bronx. I’m the youngest. I was born in 1944. My parents had two other children, a boy in 1936, and a boy in 1938.

JM: Did any of you go to college?

MM: We all did. I went to the University of Maryland.

JM: Did you have a career?

MM: I worked for the Rouse Company (real estate developer that created Faneuil Hall marketplace in Boston, and Harborplace in Baltimore). I was vice president of the corporate foundation.

JM: Did your mother work outside the home when you were growing up?

MM: Yes. She was a dressmaker, and belonged to the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. She told me that when she was just 12 years old, her father died, and she went to work in a dress factory.

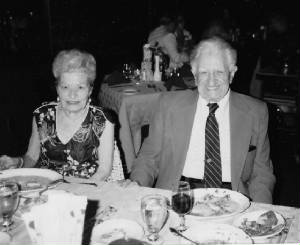

JM: What were your father and mother like?

MM: My father loved his job. The firemen were like his other family. We lived in an apartment building in the Bronx, and if there was ever a problem, tenants would knock on our door first before they called the police. They wanted my father there. I remember that we had a married couple living in one of the apartments. They were both disabled, and the man had to use the elevator. If my father was home, and he knew the elevator was out of order, he would go down and carry this man up three flights of stairs to his apartment when he needed help.

My father was quiet, but my mother was much more vocal. She was a pretty feisty lady. But she was also a kind person, and helped people when they needed help. She always spoke up if she felt that there was an injustice of any kind. She didn’t like her job sewing all day long. When I was a girl, I accompanied her to work sometimes and sat there and watched. You can’t imagine what it was like to hear the noise of all the machines going at the same time, and watch the men with the steam coming out of their irons. There were big fans blowing because there was no air conditioning. It was torture. I would bring crayons and paper, and a sandwich. I remember my mother coming home one time with her fingers bleeding because some designer decided that fiberglass would make a nice dress. That didn’t last long.

JM: Did your parents speak Italian?

MM: Yes. It was the secret language. They only spoke it when they didn’t want us to know what they were saying.

JM: What was it like living in an apartment in the Bronx?

MM: We lived in a six-story building, on the third floor, in a one-bedroom apartment, with the five of us. When a bigger apartment became available, we moved to the fifth floor. I was about seven or eight then. It was fun. We had so many friends, like maybe 30. You would go outside, and they would all be out there on the street.

JM: When did your father die?

MM: In 1990, at the age of 83. My mother died in 1988.

JM: I want to know a little about the other children in the photo. Let’s start with the girl sitting behind her mother and facing away from the camera.

MM: That was Jessamina. She was called Jessie. She never married. She stayed with my grandfather and cared for him until he died. She worked as a candy dipper until she retired. She moved to Astoria (in the Borough of Queens) toward the end of her life.

JM: Victoria?

MM: She married and moved to Pennsylvania. She and her husband didn’t have any children. She had a bad heart and died when she was about 34. I don’t have any pictures of her.

JM: Did she have rheumatic fever?

MM: Yes, and so did my father. He had an aortic valve replaced when he was in his sixties.

JM: What about Fiore?

MM: He married and had two children. He worked in the New York City sanitation department.

JM: Anthony?

MM: Uncle Tony was a police officer. He was married, and had seven children.

JM: Maggie?

MM: She died in a car accident at the age of 16. I don’t have any pictures of her. There was one more child born after the photo was taken. That was William. He became a professional wrestler. He was called ‘Tiny,’ but he was very big. He was billed as an Italian immigrant who couldn’t speak any English, but actually, he couldn’t speak any Italian. He was supposed to show no reaction when they insulted him in English. Later he became a bartender.

JM: Has going to Ellis Island and seeing the Lewis Hine photo changed the way you look at your family?

MM: I went to Ellis Island because of everything my mother had told me. She was the only child in her family that was born in this country. Her brothers and sisters were born in Sicily, and they came over after my grandfather was here for a while. She told me that one of her brothers was albino, and he was also undernourished and had rickets when they landed at Ellis Island. They were quarantined and sent to the hospital. I wanted to learn more about that, and then I found this picture of my father’s family.

My father told me that when he and his brothers and sisters were young, his father didn’t want them to speak Italian in the house anymore. But when my mother went to school, she couldn’t speak English, even though she was born here. My mother’s mother always dreamed of going back when things got better. But my father’s parents understood the American Dream right from the start. Their children may have worked late into the evening, as Hine said in the caption, but my father finished high school. I think that’s pretty incredible.

When I saw the photo, it gave me an opportunity to step back in time, and to actually enter the room where they were. I have always felt an appreciation for what I have. Our family has achieved so much since the picture was taken. I feel very proud.

(Clockwise starting with mother): Mary, Victoria, Angelina (a neighbor), Fioravanti (Fiore), Antonio (Anthony), with arm around sleeping brother Giovanni (John), and Domenica (Maggie). Girl sitting behind mother was Jessamina (Jessie).

Giuseppe (Joseph) Mauro (not pictured): 1873-1956.

Portia Maria (Mary) Toscano Mauro: 1878-1939.

Antonio (Anthony) Mauro: 1896-1948.

Domenica (Maggie) Mauro: 1900-1918.

Fioravante (Fiore) Mauro: 1901-1987.

Victoria Mauro: 1903-1937.

Giovanni (John) Mauro: 1907-1990.

Jessamina (Jessie) Mauro: 1908-1985.

William Mauro (not pictured): 1912-1974.

*Story published in 2012.