Lewis Hine caption: One-legged Boy from Pennsylvania Coal Mine. See 954. L. W. H. Location: Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania. November, 1909.

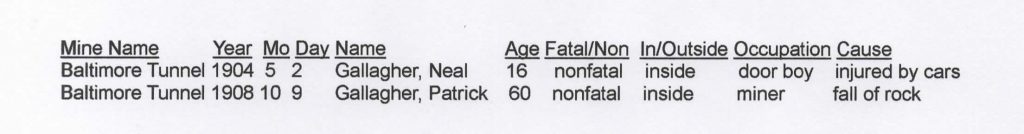

Lewis Hine caption: National Child Labor Committee No. 954. 1-legged boy. Neil Gallagher, Wilkes Barre, Pa. Born January 14, 1891. Went to work at about 9 years. Worked about two years in breaker. Went inside at about 11 years. “Tripper,” tending door. 83 cents [a] day. Injured May 2, 1904. Leg crushed between cars. Amputated at Mercy Hospital, Wilkes Barre. “Baltimore Tunnell” – “Black Diamond” D. & H. Co. Thomas Lewellin Superintendent (inside boys); Samuel Morgan, Superintendent. In Hospital 9 weeks. Amputated twice. No charge. Received nothing from company. “Was riding between cars and we aren’t supposed to ride between them.” No written rules, but they tell you not to. Mule driver (who was on for first day) had taken his lamp and he tried to reach across car to get it. Slipped between bumpers. Been working in breakers since. Same place $1.10 a day. Work only about 1/2 time. Work about 6 hour day. Left 3 months ago. Been in N.Y. – no work. Trying to get work in Poolroom. Applicant at Bureau for Handicapped, 105 E. 22nd Street, N.Y. Nov. 1, 1909. Father living, (Mother dead.) Miner same place. Hurt month ago Rock fall. 2 brothers 25, 27. Home 15 Pennsylvania St. Location: Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania.

In December 1910 and January 1911, Lewis Hine took 44 photographs in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, which was one of the centers of the anthracite coal industry in the state. He encountered young mine workers, some of them breaker boys, others mule drivers, toiling in dirty and dangerous jobs. But a year earlier, he encountered this one-legged boy in New York City, and discovered that he was from Luzerne County, and that he had lost his leg in a mining accident in 1904.

His detailed caption is riveting, and indicates that Hine must have spent more than a few moments with the boy.

Hine had spent the previous month taking almost 80 pictures of child laborers in Boston. He was about to head to New Jersey, where he would take 72 more. But on this Monday, the first day of November, 1909, he was back in New York, apparently at the office of his employer, the National Child Labor Committee, which was located at 105 E. 22nd Street, in Manhattan. The Special Employment Bureau for the Handicapped was located in the same building, and that is where Neil Gallagher was applying for help.

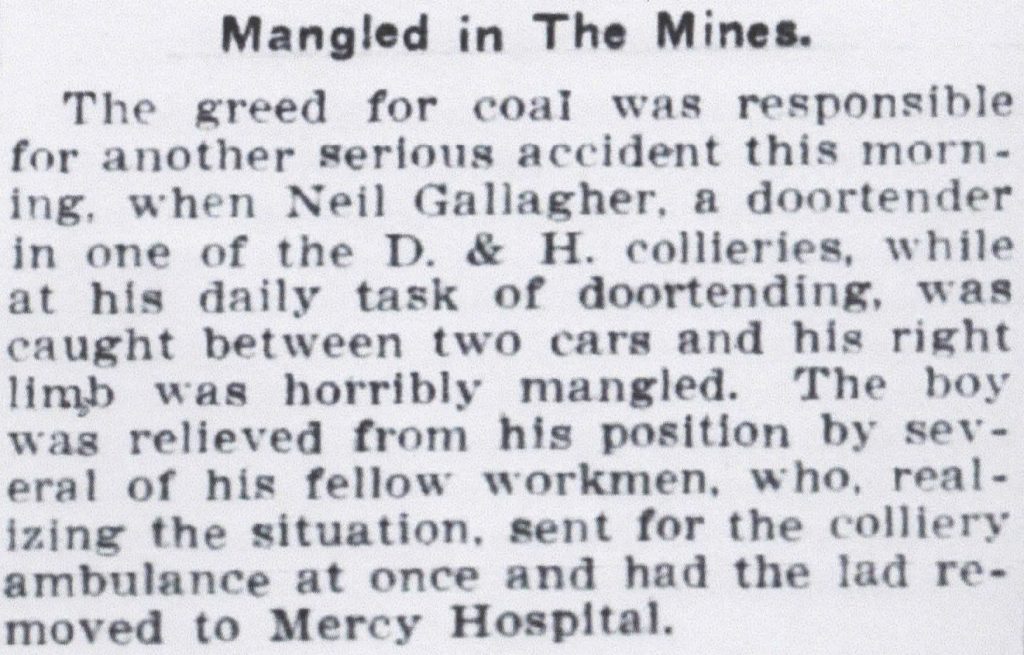

Hine probably saw Neil, apparently standing inside the office building, grabbed his camera, and approached him. When he took the first picture, he must not have known the boy’s name yet, so he referred to him only as “one-legged boy from Pennsylvania Coal Mine,” and also wrote down that his home was in Wilkes-Barre. Then he took a second picture outside, making sure it was a good one. Curious as to why Neil had come to New York, Hine asked some more questions and scribbled down some notes as Neil spilled out his sad story.

Based on the captions, this is the information I had when I began my research.

Neil Gallagher was born on January 14, 1891, which means he was 18 years old in the pictures. His home was at 15 Pennsylvania Street, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, but he had spent the last three months in New York looking for work. When he was about nine years old, he started working as a breaker boy. Two years later, he was working in the mine as a trapper (not a “tripper,” as Hine wrote). Trappers were responsible for opening and closing the underground ventilation doors. They sat all day by a door and opened and closed it when miners passed from one section of the mine to another.

On May 2, 1904, when Neil was 13 years old, his left leg was crushed when it got trapped between two coal cars. He went to the hospital, where part of his leg was amputated, and later amputated again farther up. The coal company did not pay for any of the bill, so the hospital waived the cost. He returned to work part time, again as a breaker boy, which didn’t require him to get up quickly and open a big, heavy door.

Breakers boys in South Pittston, Pennsylvania, January 1911 (Neil is not in this picture). Photo by Lewis Hine. In his caption, Hine wrote: “The dust was so dense at times as to obscure the view. This dust penetrates the utmost recesses of the boys’ lungs.” This is the job Neil returned to after he “recovered” from the accident.

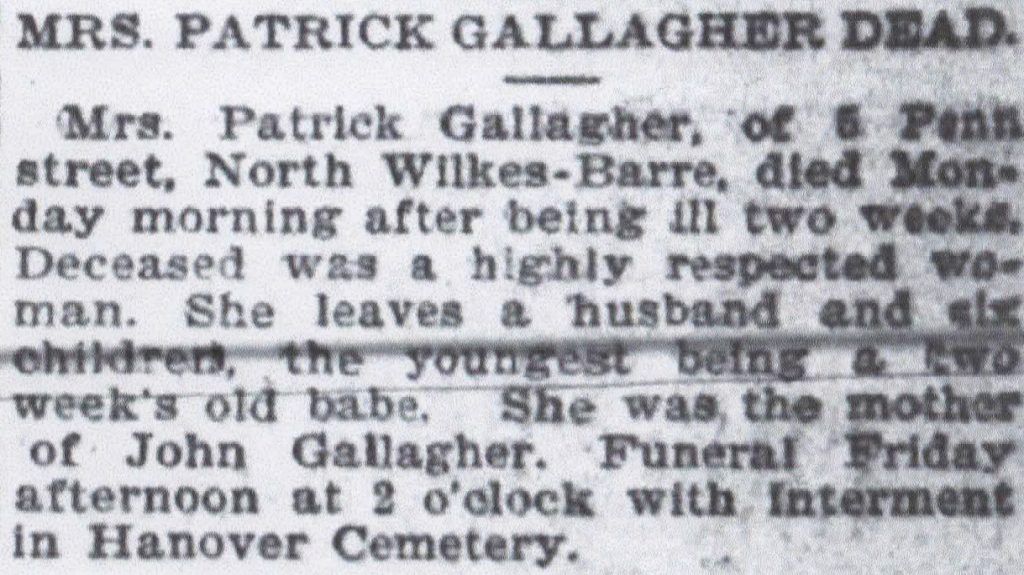

When Hine took the photos, Neil’s mother had already died, and his father had recently been injured in the mine by a falling rock. He had two brothers, ages 27 and 25, back in Wilkes-Barre.

I checked out Neil’s story about the mining accident, and I quickly found a list of mining accidents in Pennsylvania from 1899 to 1918, which are posted on the website of the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. They confirm two of the claims made by Neil in his conversation with Hine, his accident on May 2, 1904, and his father’s accident on October 9, 1908. The Commission misspelled Neil’s name (they spelled it Neal), and incorrectly gave his age as 16, rather than 13.

Of the 1,684 accidents listed in these records, only two victims under the age of 14 were listed. Both were listed as 13. At that time, the Pennsylvania child labor law prohibited children under the age of 14 from working inside coal mines. Given the thousands of young children working in the mines at that time, it is hard to believe that only two children under 14 were accident victims. Were some of the children in this list younger than reported? Were accidents involving victims under the legal age usually not reported at all? Probably yes on both counts.

What kind of a family did Neil come from? How was he supporting himself in New York? Did he finally get a job? Did he ever get an artificial leg, so he could throw away that crutch?

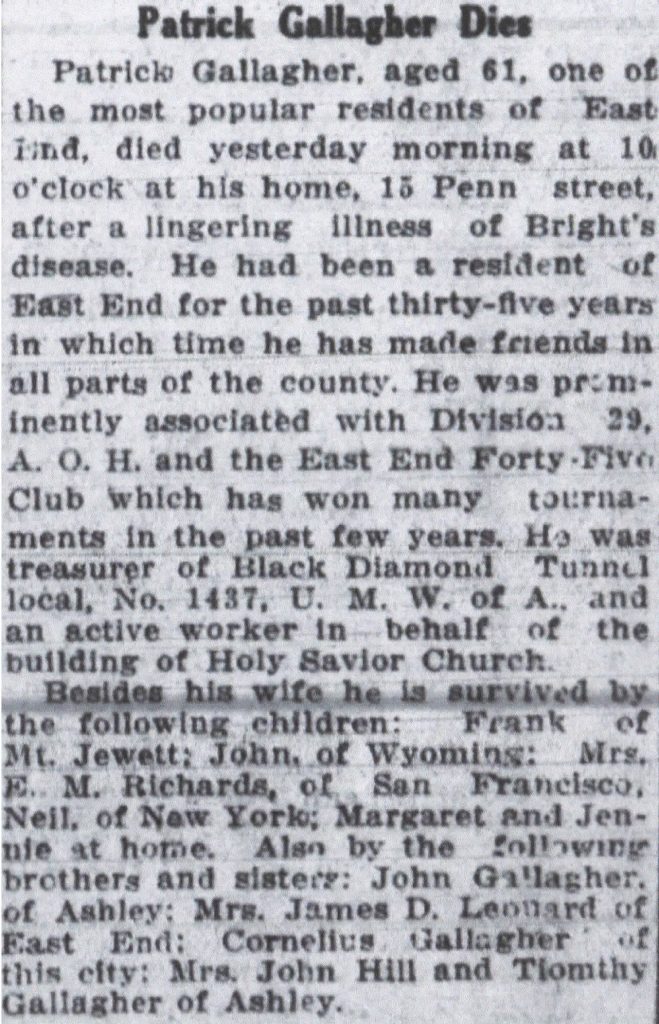

I started with the census, and there he was. On June 12, 1900, James Marsland, a census taker, entered the Gallagher home in Wilkes-Barre at 15 Penn Street (not Pennsylvania Street as Hine had stated). According to Marsland, Neil was living with his father, Patrick Gallagher, his stepmother, Dollie Gallagher, and three siblings, John, Mary and Margaret. Patrick, who owned the home, was employed in the mines, and so was his 16-year-old son John, as a mule driver. Neil was nine years old, and although the census did not list it, he may have already started working as a breaker boy, according to what he told Hine. Everyone in the family could read and write.

His father was born in Ireland in 1853, the son of Neil Gallagher and Annie Heran. He came to the US about 1868, and later married Mary Carbon. Mary died on September 28, 1896, when Neil was five years old.

Patrick married Dollie in 1898. In the 1910 census, Patrick was living with his second wife in the same house, although she gave her name as Florence, not Dollie. Patrick was still working in the mines, so he must have recovered from his injury caused by a falling rock. The only child in the home was Margaret, now 18. She was working in a lace mill. Neil was not there. Presumably he was still in New York. But the census does not record him anywhere in the US, thus leading me to guess three possible reasons: He was listed, but his name was terribly misspelled, he was overlooked by the census taker, or he had died. But I soon found his 1917 draft registration. He was living at 44 West 64th Street in Manhattan. He was self-employed as a chauffeur. He listed “lost leg” as a disability. He was described as tall, with red hair.

In the 1920 census, neither Patrick nor Florence (or Dollie) were listed, so I searched death records and located a death certificate and obituary for Patrick. He had died in Wilkes-Barre on November 6, 1913.

Neil also appears in the 1920 census, living at 1827 Washington Avenue, in the Bronx borough of New York City. He was living with his cousin, Joseph Gallagher, and Joseph’s wife and children. Joseph was an entertainer and worked in the theater. Neil (listed as Neil P. Gallagher) is listed as being born in Pennsylvania in 1891 or 1892, and his father is listed as a native of Ireland. Perhaps the “P” stood for Patrick, his father’s name. There is no one else named Neil Gallagher listed in the 1920 census that is a match, so it seems almost certain that he was the same Neil Gallagher as the one in the Hine photographs. His occupation is listed as a “hack bus driver.” Most sources define a hack bus as a carriage pulled by a horse (or horses) that transports school children. They were commonly used in New York City as recently as the 1920s.

I also found Neil in the 1925 New York census. He was living with his sister Mary and her husband, in the New York City borough of Queens. He was working as a hack driver.

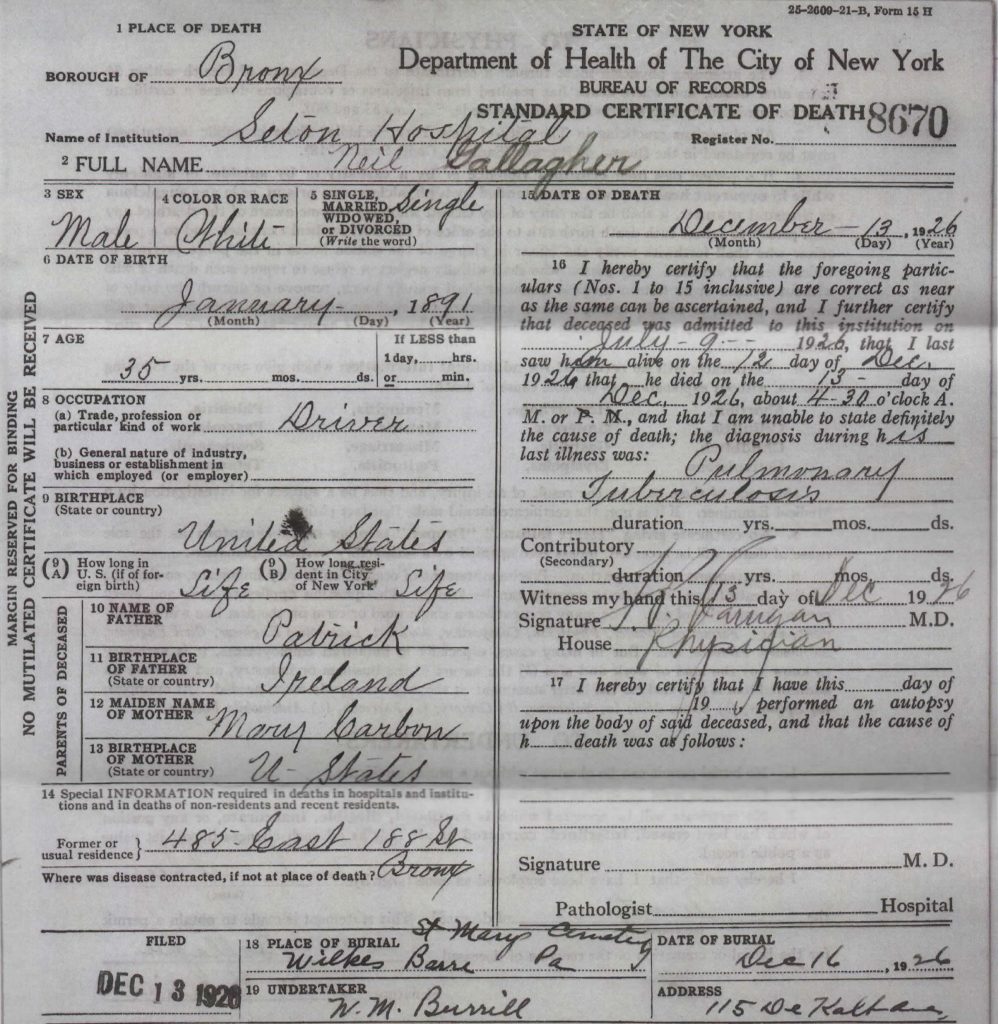

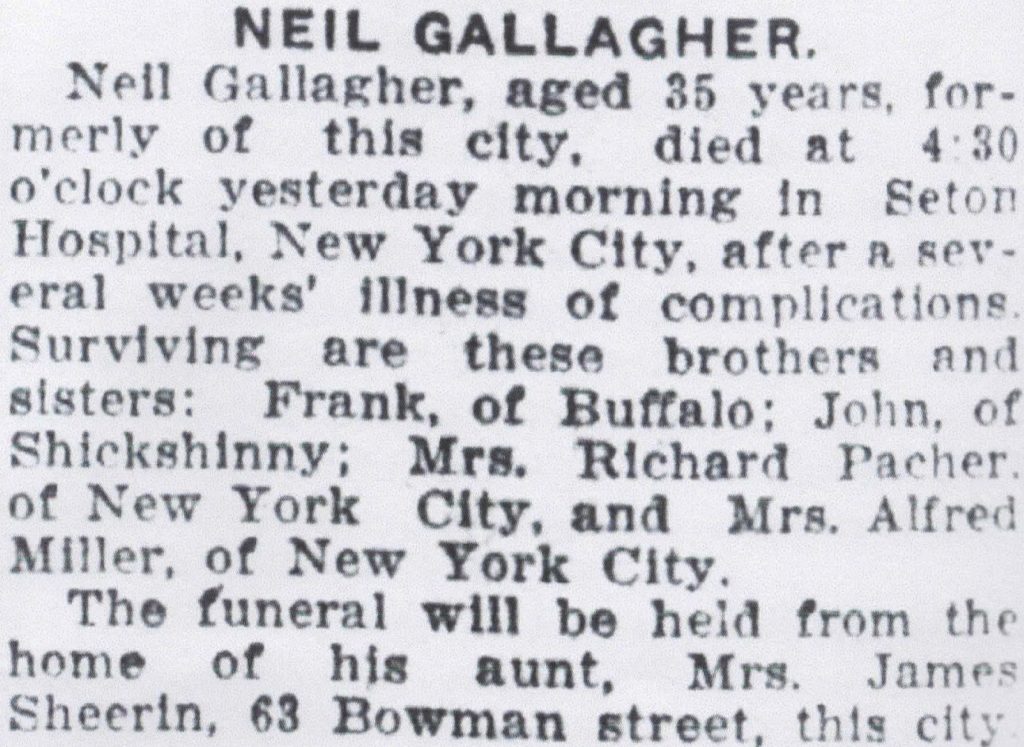

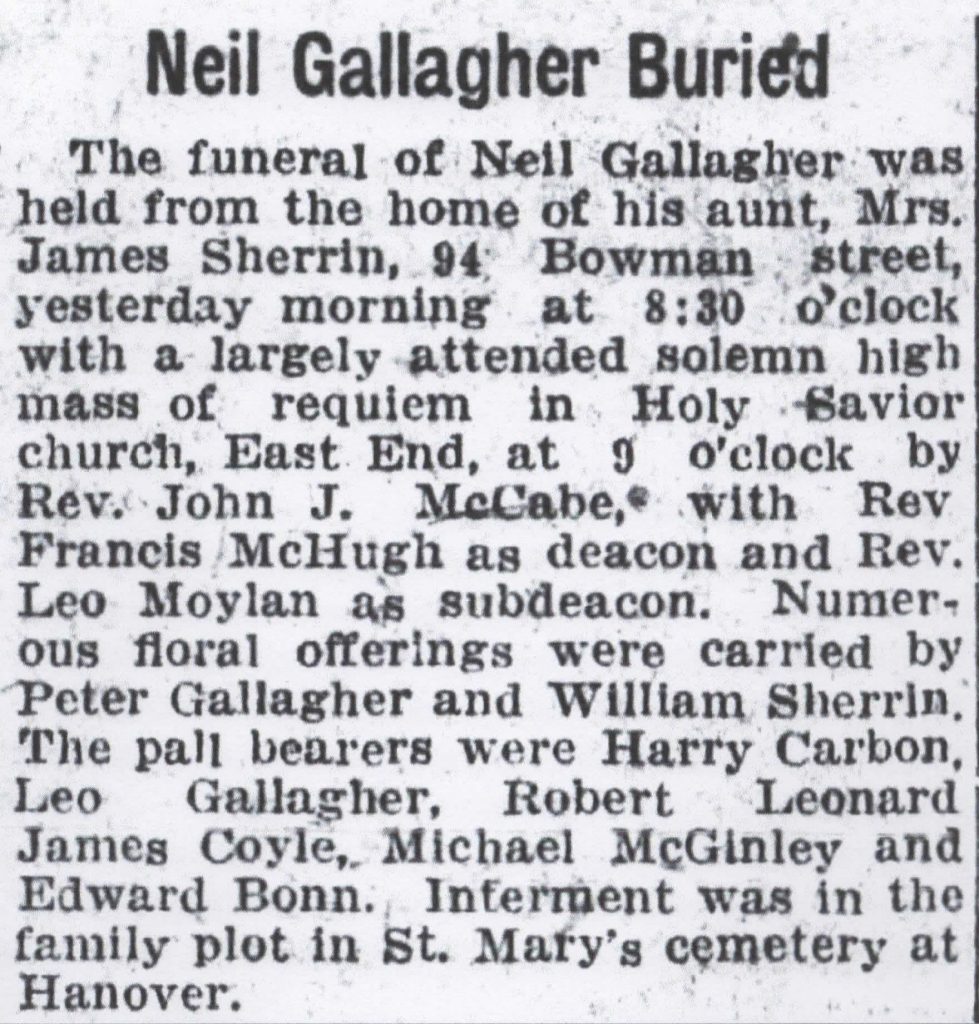

I could not find Neil in the 1930 census. So I searched death records on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org. Sadly, I discovered that he died in New York City in 1926, at the age of 35. The cause of death was tuberculosis. At the time, he was living at 485 East 188th Street, in the Bronx. I also found his obituary.

I was left wondering if he ever got an artificial leg, and if not, how he managed to drive a hack bus. The answer may lie in this, which appeared in a 1907 report by the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York. It described the work of the Special Employment Bureau for the Handicapped, where Neil had applied for help.

“To study the abilities of persons handicapped physically, mentally, or socially; to find work adapted to their powers which would enable them to be wholly or partially self-supporting; to persuade employers to accept a responsibility toward them, were the tasks which had to be faced in establishing this Employment Bureau. There were no precedents for method, as this was the first attempt of the kind ever made, and the early months were necessarily experimental.”

“The methods which are now being pursued by the Bureau include keeping an accurate record of each applicant’s qualifications, frequently with a physician’s opinion as to what kinds of work are permissible, and of the Bureau’s experience with him; patiently building up a list of employers whose assistance can be counted on; finding among the applicants persons who can fill positions offered, actively seeking positions for the others; providing training for some, and medical assistance for others in order that they may become qualified for new tasks.”

“During the eighteen months since the Bureau began work 1,137 applications have been registered and 450 placements made, a ratio of two placements to five applications. Considering the character of the labor offered and the prejudice of most employers against an employee in any capacity who is not able to work at full speed, the results are very encouraging.”

“A descriptive analysis has been made of the 596 new applications and the 314 placements of the seven months ending September 30. The largest group among the new applicants was of those disabled by some crippling disease, generally rheumatism, numbering 125; 120 were convalescents; 94 were handicapped by age; 56 were in an early stage of pulmonary tuberculosis and 17 more were suffering from other forms of tuberculosis; 25 were partially blind, two totally blind; 20 had lost a hand, 17 a foot, and two more than one limb; 17 were mentally diseased and four were mentally defective.”

Two quotes stood out: “20 had lost a hand, 17 a foot, and two more than one limb,” and “providing training for some, and medical assistance for others in order that they may become qualified for new tasks.”

Did the agency find a way to get him trained to drive a hack bus? It appears that they did. Did they pay for an artificial leg? We may never know.

This story was originally published on my website in 2011. But at that time, I could find no records for Neil after 1920, not even a date of death. So I published what I had, hoping that someone reading the story might know more about Neil, and contact me.

Six years later, in the summer of 2017, I was contacted by a man who was looking for information about Lewis Hine. He wanted to know where the National Child Labor Committee office was located when the organization hired Hine in 1908. He was planning a trip to New York City and wanted to visit the location and take some pictures. I sent him the Hine photo of Neil standing in front of the building, at 105 E. 22nd Street, where the office was located. I asked him if he would bring the photo with him when he visited the building (if it was still there), and try to photograph the building from the exact spot that Hine took his photo. He said he would be happy to do it.

Having been reminded of my story of Neil, I decided to make another attempt to find out what happened to him after 1920. With considerably more historical records now available online, I was hopeful. It took me only a few minutes to find Neil’s death record. And I discovered that the searchable archives of the Wilkes-Barre newspaper are now available back to the late 1800s.

Thanks to Aaron Warwick, the man who contacted me, for the photos below.

*Story originally published in 2011, and updated in 2017.