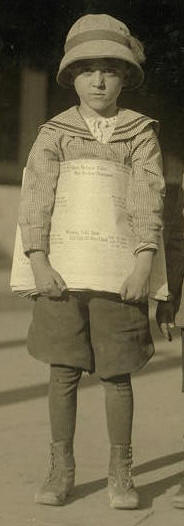

Lewis Hine caption: Two six-year old newsboys. Odell McDuffy, Sam Stillman, Dallas. There are many other of six and seven years selling here. Location: Dallas, Texas, October 1913.

“He played for the Panhandle Oil Company, in the Texas League. He was a pitcher. He had a catcher named Tank Horton. Tank told me that my stepdad was the best knuckleball pitcher he ever saw in his life. He told me he would walk out on the pitcher’s mound before a ballgame and wet his finger and hold it up, and if that breeze was coming from the catcher toward the pitcher, he would say, ‘The batters are gonna have a bad night tonight.'” -Lee Riley Welch, stepson of Odell McDuffey

“He was very interested in sports. He loved to go to baseball games especially. I went to the games with him a lot. He would watch the game, but he had a portable radio, and he would listen to another game at the same time.” -Damie Stillman, son of Sam Stillman

These two boys were probably standing in a busy downtown section of Dallas, where many of those that walked by relied on reading the newspaper every day, and had ready change in their pockets. Note the three well-dressed people who have just passed. The lady on the left is looking back, well aware of the camera. From what little Hine tells us in the caption, he must have asked the boys how old they were. Apparently, they said nothing else of significance. He would not have known any of what I know now.

Odell had lost his father 18 months earlier (April 1, 1912), when the family was living on a farm in Fannin County, Texas, near the Oklahoma border. His father’s ancestors, probably Irish, had settled in North Carolina in the early 1800s. For reasons unknown, Odell, his widowed mother, and his two sisters moved to Dallas.

In stark contrast, Sam’s father, a Jew, had fled Russia in 1907, gone to Bremen, Germany, and then sailed on a boat called the Chemnitz. He landed in Galveston on August 24, 1907, and settled in Dallas. Almost three years later, Sam, his mother, and his five siblings also came through Bremen, and sailed on the Hannover, which landed in Galveston on April 28, 1910.

Standing together on a Dallas street on an autumn day in 1913, would the two boys have comprehended the significance of the entirely different routes they had taken to get there, and the opportunity that America had given them to share that brief moment, despite their differences? Their lives were destined to take different routes once again, though as we see in the quotes above, each of those routes were to travel through the world of baseball, the most American of games.

I will start with Odell’s story.

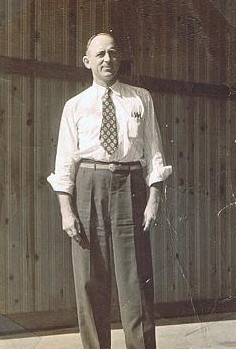

Collins Odell McDuffey was born in Ector, Texas, on January 8, 1907, to John Collins McDuffey and Stella (Truitt) McDuffey. He did not stay in Dallas very long, because in the 1920 census, he is living in Wichita Falls, Texas, with his mother and a 15-year-old sister, both of whom work as salesladies. He married Donna Mitchum in 1927. According to the 1930 census, they were living in Wichita Falls with her parents. They had no children. Odell was a clerk in a grocery store.

Odell and Donna apparently divorced, because in 1935, he married Maedell Cawley, who already had a son from a previous marriage. They did not have any children of their own. Odell worked most of his life as a tire salesman and dealer. Maedell died in 1971. Odell died in Wichita Falls on June 17, 1987, at the age of 80.

I found his stepson, Lee Riley Welch, and a great-niece, Kathy Moyers, neither of whom had ever seen the Hine photo.

Edited interview with Lee Riley Welch (LW), stepson of Odell McDuffey. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on May 21, 2010.

JM: What did you think of the photo?

LW: There’s no doubt it’s him. His father died at an early age, so I’m sure he had to work when he was pretty young.

JM: The picture is in the Library of Congress.

LW: That’s something he would have liked to have known, I’m sure.

JM: What year were you born?

LW: 1928. He married my mother when I was seven years old. My mother and my real father had divorced when I was three years old.

JM: Was he called Odell, or Collins, his first name?

LW: Odell. It was kind of a funny thing. He had a brother named Othell, a sister named Adelle, and my mother’s name was Maedell. That’s a bunch of Dells.

JM: What was he like as a stepfather?

LW: He was one of the finest fellows I ever met. We fished together; we hunted together. We lived out at my grandmother’s for a while. She had a great big home in Wichita Falls. She was by herself. We had a big garden, and he and my mother would come home in the evening from work, and we’d all go out and work in the garden.

JM: What did he do for a living?

LW: When he was younger, he managed the tire department for Sears Roebuck for about 30 years. He owned his own tire store in later life.

JM: How far did he get in school?

LW: He went through high school and one year of business college. He was very sharp, and an awful good salesman. He was a very down-to-earth fellow.

JM: What do you miss about him?

LW: Fishing with him. When I was about 11 or 12, we used to put out trotlines and fish on weekends. We’d run a trotline across the Red River in Wichita Falls, and when the water would get too deep for me, I’d wrap my legs around his waist, and we’d go on across the deep part.

JM: That must have been a little scary.

LW: Well, I was with him, so it wasn’t scary to me.

JM: Where did you live when you were growing up?

LW: We lived on 2235 W. Virginia Street. At that time, it was a dirt street, all the way out from town. The WPA came out there once and built a bridge across Holiday Creek. It was four lanes wide and 60 yards across.

JM: I have a record that Odell lived at 3211 Cumberland Avenue.

LW: That was an apartment right across the street from a drugstore. We lived there about 10 years, and then he and my mother finally bought their own home. That was on North 10th Street.

JM: You told me that he played baseball.

LW: He played for the Panhandle Oil Company, in the Texas League. He was a pitcher. He had a catcher named Tank Horton, who went on to play for the St. Louis Cardinals. In later years, I knew Tank Horton, because after he retired from baseball, he came back to Wichita Falls and owned a bar. I was in there with my stepfather on lots of occasions. Tank told me that my stepdad was the best knuckleball pitcher he ever saw in his life. He said he could’ve competed with anybody. Back in those days, Odell would play ball three or four nights a week, and a pitcher can’t do that. So he eventually threw his arm away and had to give up the game. Tank told me he would walk out on the pitcher’s mound before a ballgame and wet his finger and hold it up, and if that breeze was coming from the catcher toward the pitcher, he would say, ‘The batters are gonna have a bad night tonight.’ When Odell got to throwing that knuckleball into the wind, it was tough to hit.

JM: How big was he?

LW: About 5′ 11″, and he weighed about 175 pounds. He was very athletic.

JM: After he stopped playing, did he continue to be a baseball fan?

LW: Oh, yes. He was a St. Louis Cardinals fan, because of Tank Horton. They were friends a long time. Tank was at his funeral.

JM: He lived to be 81. Was he in pretty good health most of his life?

LW: He was in pretty good health up to when my mother had a stroke and passed away. After that, he kind of went down pretty fast. Living by himself didn’t help. Eventually we had to put him in a nursing home. After we got him in the nursing home, we learned that three checks he had written to a local store couldn’t be cashed because the bank wouldn’t honor them. They said it was because his signature was so bad.

I told him, “We got a problem, Papa. The bank won’t honor your signature, because you don’t write worth a damn anymore.’ He kind of laughed and said, ‘Well, that’s the truth.’ I knew him better than most people, and I knew he worshipped my wife, Ruby. So I told him I had a suggestion. ‘Why don’t you let me go to the bank and get a bank card and you sign it and let Ruby sign it, and any checks you need to write, she can write them for you.’ And he said, ‘That’s a great idea.’ Now if I had said, ‘You let me sign the checks for you,’ that wouldn’t have been worth a damn. But he thought the world of my wife, and she wound up writing his checks till he passed away.

Excerpts from my interview on June 18, 2010, with Kathy Moyers, great-niece of Odell McDuffey.

“The photograph was amazing. I shared it with my grandchildren, and they were all excited. For me personally, it was an enriching experience, because I didn’t have much knowledge of his early life. Uncle Odell was my father’s uncle. We saw him every time we went to Wichita Falls. He was just a very dear man.”

“I had no idea that he was selling newspapers when he was six years old. It’s a tragedy we had to put kids to work, but from a philosophical standpoint, it’s an example of how, in our American culture, we can persevere, and even bad experiences can strengthen us. He ended up being a very successful businessman, and very self-assured.”

“He was one of my favorite relatives. I admired him because of the stories that my father shared about him. My father never really knew his father, who was an oil field worker. He married my grandmother when she was very young, and my father was born when my grandmother was only 16 years old. They lived in sort of a tent city. They separated when my father was very young. So I think that Odell was the closest male role model he had. He used to take my father fishing a lot when he was growing up.”

“Uncle Odell was sort of a man’s man. He was very self-sufficient. He loved to fish, and he’d take his beer with him. As he aged, I continued to visit him. I think I was in my mid-thirties the last time I went to see him. It was hard for him to walk, and he stayed mostly in his bedroom. He had a small refrigerator, a hydraulic chair and a TV. When he was in pain, he would ask me to go get his whiskey, and he would pour himself a shot. I am sure he was not an alcoholic, but he was a drinker.”

“My fondest memory was when he took us to his Firestone dealership to show us his inventory of tires, which included those huge tractor tires. Just walking through that store and smelling the new rubber; that still brings back memories. Whenever I smell new tires, I always think of Uncle Odell. He was full of life and full of stories. He would bring out his scrapbooks and picture albums and share them with me. When he was bedridden in his last years, I would call him to see how he was doing, and he would say, ‘I’m just layin’ here dying.’ He had a great sense of humor, and he was a joy to have in the family.”

**************************

Story of Sam Stillman

Isaac Samuel Stillman was born in Russia on December 7, 1906, according to the family. He was one of eight children born to Hyman and Gertrude (Tenberg) Stillman, who were married about 1885. As stated earlier, Hyman had come to Dallas from Russia in 1907, and the rest of the family joined him in 1910. In the 1920 census, the family is listed as living at 2117 Leonard Street, where they are renting a house. Hyman is the proprietor of a dry goods store.

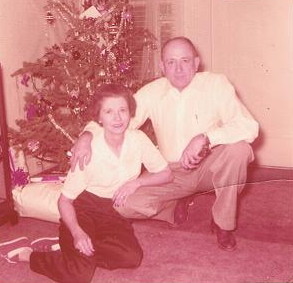

In the 1930 census, recorded in April, Sam is listed as living with his parents at 3217 Cleveland Street. Hyman works as a “church collector,” and Sam is a bookkeeper for a clothing store (The Model Tailors). There are two persons boarding with them, Esther Damie and her 23-year-old daughter, Fanita. Later that year, Sam married Fanita. They would have one child, son Damie, who was born in 1933. Sam’s mother died in 1932, and his father died in 1938.

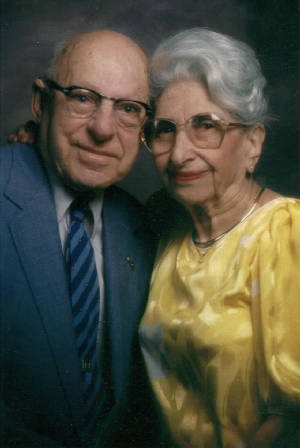

Fanita died in 1957. Sam remarried, but was widowed again, then married a third time. He continued to work as a bookkeeper and accountant, and lived in Chicago and Florida, before returning to Dallas about 1987. He passed away on February 14, 1993, at the age of 86.

Late in his life, Sam was interviewed for a book called Deep Ellum and Central Track: Where the Black and White Worlds of Dallas Converged, by Alan B. Govenar and Jay F. Brakefield. In the first half of the 20th century, the Deep Ellum section of Dallas became a hotbed for jazz and blues. Nightclubs such as The Harlem and The Palace featured blues icons such as Robert Johnson, Leadbelly, Bessie Smith and Blind Lemon Jefferson. According to the interview with Sam, Jefferson had his clothes made at The Model Tailors, where Sam worked as a bookkeeper.

After obtaining Sam’s obituary, I contacted son Damie, who lives in Baltimore.

Edited interview with Damie Stillman (DS), son of Sam Stillman. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on June 7, 2010.

JM: What was your reaction to the photograph?

DS: I was surprised, because, although I knew my father was the youngest of eight children and worked to help the family, I didn’t realize that he was selling newspapers as young as seven years old.

JM: Mr. Hine was trying to tell the public that children shouldn’t be doing this, and that there should be child labor laws to prohibit it.

DS: It doesn’t strike me that the photograph actually shows that very well. For one thing, both boys are pretty nicely dressed. There are well-dressed people in the background as well. My field is art history, and I taught courses in American art. In doing so, I would talk about photography. When I covered the early 20th century, I would show some of Hine’s work. Of course, I knew that he had photographed child laborers, though I certainly didn’t know that my father was one of them. I’ve seen much worse examples of child labor, and I’m not sure how successful this picture would have been in stimulating opposition to it.

JM: Did your father ever tell you that he did anything like this?

DS: I don’t remember. I do know that he was the only one of his parents’ eight children to graduate from high school and go to college. He went to Southern Methodist University. He graduated from high school in mid-term, and then went to SMU the rest of that year. But then he quit, probably because he still needed to work and help support the family. He was still living with his parents then.

JM: How could his family afford to send him to college, even for a short time?

DS: By that time, the oldest children were out of the house.

JM: When did the family come to the US?

DS: My paternal grandfather came about 1908 (confirmed later as 1907), and the rest of the family came about a year or two later (confirmed later as 1910). They came through Galveston.

JM: According to the 1920 census, your grandfather was the proprietor of a dry goods store, and your father was the only child living in the home.

DS: I didn’t know that my grandfather had a store.

JM: Did you know him?

FS: Vaguely. He died when I was about four years old. My grandmother died the year before I was born.

JM: When were you born?

DS: 1933, in Dallas.

JM: How many children did your father have?

DS: I’m the only one.

JM: What was your mother’s name?

DS: Fanita Damie. That’s how I got my first name. She was born in St. Louis. Her parents were Jewish immigrants who first settled in Oklahoma, when it was still Indian Territory.

JM: How did your father and mother meet?

DS: After my mother’s father died, she and her mother became interested in owning a drugstore. My mother studied pharmacy and then went to Dallas in order to get certified as a pharmacist. Apparently, certification in Texas qualified you to practice in a number of other states. Someone told her about my paternal grandparents having a house, so she and her mother rented space there for a while. That was on Cleveland Street, in South Dallas. My mother was working as a pharmacist at night in a local drugstore, and my father started going to pick her up, in order to make sure she got home safely. Pretty soon, he proposed to her. They got married in 1930.

JM: I read some information about the neighborhoods in Dallas, and I learned that South Dallas was a Jewish neighborhood at that time.

DS: Yes, that’s correct.

JM: Where did your parents live right after they married.

DS: I don’t know exactly. I know they lived in a place of their own in South Dallas before I was born. They lived in a house on Colonial Avenue about the time I was born. When I was not quite four, my parents bought a house in East Dallas, and that’s where I grew up. It was on 6700 San Mateo Avenue Blvd.

JM: What was your father doing for a living when you were born?

DS: He was a bookkeeper and accountant for a firm called Model Tailors. He started working there shortly after he left SMU and remained there until 1945. The company had about 20 employees and was in a two-story building in a section of Dallas called Deep Ellum.

JM: What did your father do immediately after he left Model Tailors.

DS: My mother was still a pharmacist, and she had a drugstore. So he started working there. He kept the books and also waited on customers and did various other things. My mother died in 1957. After she died, my father moved to Chicago, where I had an aunt. He soon remarried. He worked there as a bookkeeper for 25 years, and then retired to Florida. Then his second wife died.

JM: What was his second wife’s name?

DS: Celia Maram. She died in 1986. Right after that, a woman who had lived next door to my father in Dallas started writing to him. She had lost her husband. My father had jilted her long before to marry my mother. They finally got married and he moved back to Dallas. He spent the last six years of his life with her in Dallas. Her name was Gertrude.

JM: What was your father like?

DS: He was warm, human, and had a good sense of humor. He was a voracious reader. He was very interested in sports. He loved to go to baseball games especially. I went to the games with him a lot. He would watch the game, but he had a portable radio, and he would listen to another game at the same time. I also remember going to football games with him at the Cotton Bowl. He was interested in world affairs and politics. He was one of only 76 people in Texas who helped elect Lyndon Johnson to the US Senate in 1948. He was liberal politically. He told me that he stayed up all night to listen to Roosevelt get elected in 1932.

JM: When did you leave Dallas?

DS: I went away to college in 1951. I went to Northwestern, in Illinois. I studied art. My mother was interested in lots of things, including music and art. I’m sure that’s where I developed my interest in art. I went to graduate school at the University of Delaware. And then I got a Fulbright Scholarship to the Courtauld Institute of Art in London in 1956. I finally got my doctorate at Columbia.

JM: Why did you move to Baltimore?

DS: My wife was offered a job as Director of Education and Public Programs at the Walters Art Museum there. I commuted to the University of Delaware, where I was teaching.

JM: When did you retire?

DS: In 2000.

JM: How often do you go back to Dallas?

DS: Not very often anymore. After I left, I didn’t go back for 20 years, because my father wasn’t living there. I went back in 1978 when I was invited to lecture at SMU. I went back there in 1986 when my father married his third wife, and then I went back there at least once every year while he was still living. He died of a stroke in 1993.

JM: It seems like quite a leap from selling newspapers on the street at the age of seven, to having a son who got awarded a Fulbright Scholarship.

DS: That’s what’s incredible about this country. Children of immigrants have been given opportunities to pursue successful careers.

Odell McDuffey: 1907 – 1987

Sam Stillman: 1906 – 1993

*Story published in 2010.