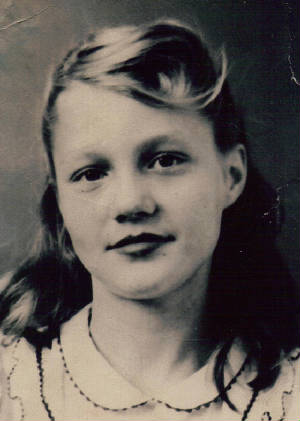

Lewis Hine caption: Rosy Phillips. Fifteen year old spinner in a Dallas cotton mill. She was far from “rosy” – thin, anaemic. Prematurely old. Her brother Exie [?] twelve years old who helps her some on Saturdays. He said: “I can’t get a steady job, but I can help her all I want to.” I did not see any others very young. Location: Dallas, Texas, October 1913.

“When I saw the pictures, I was kind of stunned, and then I broke down and cried. I never had any pictures of my mother as a young person. So really, that was…well…for three or four days, I just kept getting out the pictures and looking at them.” -Beatrice Earl, daughter of Rosa Phillips

Lewis Hine caption: Group of typical mill girls. Dallas Cotton Mill. Location: Dallas, Texas, October, 1913.

The following is from the Texas Dept of Agriculture Bulletin, July-August 1909:

The Dallas Cotton Mill was the first expensive enterprise of the kind undertaken in Texas. It was incorporated in 1891 and capitalized at $250,000. At this time it represents an investment of $400,000. It contains 360 looms, 12,000 spindles and employs 325 hands when working a full crew. It consumes 7000 bales of cotton per annum. It manufactures duck, sheeting and drilling, which it sells in various parts of the world. Within the last few weeks, prior to the time of my visit, it had shipped goods to Mexico, Massachusetts, Seattle, Chicago, Los Angeles; and at other times to South Africa and China. There are a few more boys than girls in this mill; about 65 per cent of the grown persons are men. This mill, as well as the mills at Itasca, Waxahachie, Sherman, Denison and Bonham, use coal for fuel instead of lignite, procured from Oklahoma and Arkansas.”

“This is the third company since the organization of this mill, the manager informing me that very few mills in Texas ever paid the original stockholders anything, thereby necessitating the usual foreclosures, reorganization and the like. However, the mill is prospering now. Last year it added $25,000 worth of new machinery. With reference to labor the manager said: ‘Practically not a hand have I ever gotten from Dallas and the farms of this State. We import all our hands from the Southern States east of the Mississippi river, a great many of them coming from Mississippi and Georgia.’ The company owns about thirty cottages, the rents ranging from $6 to $10 per month; owing to the number of rooms. Water, as at all the other mills, is plentiful and free to the operatives. Coal for the cottages is furnished by the company at cost. Most of the houses have sewerage connections. One of the largest ward schools in the city is within four blocks of the mill. The manager expressed himself as being in favor of compulsory education.”

“‘The small children,’ he said, ‘not of mill age in the mill village spend their time in idleness and cause trouble to their parents as well as to the mill and the entire community.’ The average man in the mill, I was informed by the manager, makes from $1.50 to $2 per day. He illustrated the earnings of an average family in the mill as follows: A man comes to the mill with his wife and four children, the man earning $1.50 per day; the daughter, if she is grown, will earn $1 per day; one son, from 14 to 16 years of age, will make 75 cents per day; the other child, a daughter near the age of the son, will make 65 cents per day. The total earnings of the father and three children will be $3.90 per day, or $97.50 per month. The mother remains in the house, where she attends to the domestic affairs of the family. At the same time the family is comfortably housed, protected from the hot sun and the cold winds. ‘Compare this family’s wages, condition and surroundings generally,’ continued the manager, ‘with the tenant farmer, and the difference will be in favor of the family in the mill.'”

“The manager predicts that Texas will be the cotton mill State of the Union, it being a question largely of population. ‘I would rather pay 10 to 12 cents a pound for cotton than to get it for 8 cents, because it means more-profit to the country and better times generally,’ remarked the manager. With reference to climatic conditions, he said: ‘The inventive genius of man has overcome the defects in the atmosphere, if any ever existed.’ It is his opinion that we are as well supplied with labor as any of the other Southern States.

Lewis Hine caption: Group of workers at the Dallas Cotton Mill. The small boy helps his sister. Eternal vigilance will be needed to keep these little ones out of the mill. Location: Dallas, Texas, October, 1913.

Rosa Mae is the girl in the bottom row, third from the right. Exie is the boy in front. Due to their striking resemblance to Rosa, and based on the census information, it is virtually certain that the boy on the left in the bottom row is brother Jefferson Phillips, and the girl next to him is sister Mamie Phillips. After Rosa’s daughter Beatrice saw this picture, she made a stunning observation. “Look at Uncle Exie’s fingers. He is making an X, for Exie.”

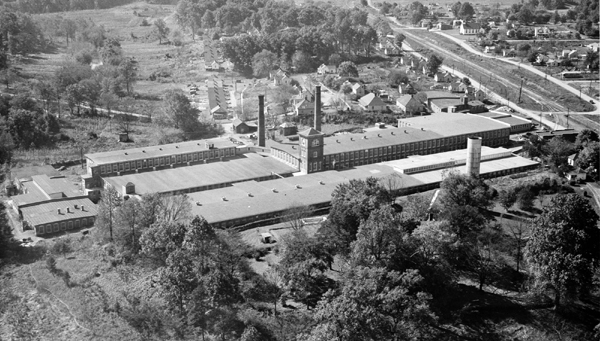

Lewis Hine caption: Noon hour at the Dallas Cotton Mill. Location: Dallas, Texas, October 1913.

When Rosa and Exie posed for Lewis Hine, they and their siblings would have already lived through more than their share of struggles. Their father, John Robert Phillips, was born in Georgia in 1861. He married Dycia (Dycie) Ratliff in Alabama on August 29, 1886. She was born in Alabama in 1868. In 1900, they and their eight children were living in New Decatur, Alabama, where John was a blacksmith. Their first two children had been born in Tennessee, the next in Alabama, the next four in Texas, and the last, three-month-old Rosa Mae, back in Alabama. In 1910, they were living in Dallas, where John was a farm laborer. They had three additional children, all born in Texas. One of them was seven-year-old Exie. Their three oldest children were no longer in the home.

By 1920, Rosa had married Frank Lamb, a Mississippi native. They were living in Mooney, Phillips County, Arkansas, where Frank was a farmer. They had no children yet. According to Rosa’s daughter, Beatrice Earl, she was told by her father (Rosa’s second husband) that Rosa and Frank had three children, all of whom died young. In about 1925, Rosa moved to Danville, Virginia to be near a sister, either because she and Frank got a divorce, or because Frank died. This has yet to be established. Rosa married John Boone in Virginia, in 1926, and they eventually moved to North Carolina. Rosa and John had seven children, but only two survived childhood, Beatrice and her sister Elsie.

Rosa Mae Phillips, born on February 23, 1900, died of leukemia in Fayetteville, North Carolina, on October 19, 1941. She was 41 years old. Her mother died in Dallas a year later, and her father died in Texas in 1951. Her husband John died in Colorado in 1977.

Exie Barton Phillips was born on October 25, 1903. In 1930, he was single and living his brother, William, in Dallas, and was a laborer for an oil company. He died in Fort Worth, Texas, on November 11, 1955. He was survived by his wife and one daughter. I was unable to locate any living descendants.

Mamie Phillips, one of two other Phillips children who appear to be identified in the group picture by Hine, died in Fayetteville, North Carolina, on July 24, 1961. Her married name was Mamie Alexander. Jefferson Phillips, the other child, appears in the 1920 census, living in Danville, Virginia, with wife Doshia, and daughter Estelle. I could find no further information about him.

Edited interview with Beatrice Earl (BE), daughter of Rosa Phillips. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on November May 4, 2010.

JM: What did you think when you saw the pictures?

BE: I was kind of stunned, and then I broke down and cried. I never had any pictures of my mother as a young person. I only have a few pictures of her after she married my daddy. I only met maybe three of her sisters. So really, that was…well…for three or four days, I just kept getting out the pictures and looking at them.

JM: Did you recognize her?

BE: Oh, yes. I’ve been told that I look at lot like her. And even though I never met my Uncle Exie, his face looked familiar.

JM: What do you think about your mother being photographed in that situation, and that the picture was used to influence the passing of child labor laws?

BE: What struck me was how poor she and Uncle Exie looked. Her sisters that I stayed with the two weeks before she passed away were middle class people, cotton mill workers at Pearces Mill, near Fayetteville. We lived in a town called Lake Dell. That’s where my mother passed away. It saddened me, because there she was, just a little 13-year-old girl, and she was so shabby. It bothered me. It still bothers me.

JM: When were you born?

BE: I was born March 26, 1934, in Hillsboro, North Carolina. They spell it Hillsborough now. We lived on Hill Street then.

JM: How did your mother wind up in North Carolina?

BE: I was told by my father that my mother married in Little Rock, Arkansas, at the age of 15, to a man named Frank Lamb. My mother had an older sister in Little Rock, and met Frank there. I don’t know how long she was married to him. She was supposed to have had three children by him. But then she married my father on July 10, 1926, in Danville, Virginia. How she got to Virginia, I have no idea. Then my parents moved to North Carolina, but we lived briefly in Virginia again in about 1937 or 1938. I also remember going to Virginia once to visit this beautiful black lady who had lived with us and took care of my sister and me while my mother worked in the Eno Cotton Mill in Hillsboro.

JM: What happened to the three children that your mother had with Mr. Lamb?

BE: On my birth certificate, it says, ‘Ten children born, only two living.’ They were either stillborn, or died soon after birth. My sister and I were the only children left. I was not named on my state certificate because my mother was afraid that I was not going to live. I had to get an affidavit to prove who I was, so I could get a new state birth certificate. But she did name me on the county certificate.

JM: What happened to the first husband?

BE: I don’t know. When I tried to find out more about my mama’s family, one of my cousins wrote me a letter and said, ‘Well, it’s best if you just leave it alone because you might find out things that you don’t like.’ That is foolish, because when you’re trying to know more about your family, it doesn’t matter what they’ve done. You just want to know them.

JM: What did your father do for a living?

BE: When he worked, he worked in the cotton mill. I don’t remember my daddy being around much. It seemed like he would come and go. He didn’t get along very well with my mother’s people in Fayetteville.After my mother died, we moved to Fayetteville, and he went to work at Fort Bragg, where he was a mechanic. He married again in 1943.

JM: How did your mother die?

BE: She was diagnosed with leukemia in March of 1941, and she died October 19th of that year. In early October, we all went to stay with my Aunt Mamie, my mother’s sister. It was kind of rough, because it was hot. We had all the doors open. My mother was off to one bedroom, and my Aunt Mamie was ironing some clothes, and I was sitting on the bed with my mother. She wanted a Pepsi. That’s when you had the glass straws that the hospitals had. I got her the Pepsi, and I put the straw in the bottle. She held her head up a little and I held the bottle for her. She took a few sips, and she started choking, and then she was gone, just like that. I didn’t realize what had happened, but I knew that something was wrong. Aunt Mamie kind of got a little hysterical. I just kept saying, ‘Mama, Mama.’ And that’s how she died.

Her death certificate was never filed. She had only been in Fayetteville for two weeks when she passed away. Her doctor verified the death but never filed it with the city. All I have is the record of the funeral. She was buried in the city cemetery. My daddy paid for it. It was $175, and he went into debt to do it. I went back in 1977 and tried to find her grave, but the cemetery was so desecrated, I couldn’t find it. The funeral home (Jernigan Warren Funeral Home, in Fayetteville) sent me the record of her death. It says she was survived by five sisters and four brothers.

JM: After she died, who took care of you?

BE: I stayed with Aunt Mamie, my mother’s sister. We all lived there for a while, my daddy and my mother and sister and I, until my mother passed away. We stayed with Aunt Mamie for a few weeks, and then we moved to a place called Godwin, which was just a little community of railroad houses or boxcar houses, one after the other. It was a near Fayetteville. I became pretty ill there with jaundice and was in the hospital for quite a while. That’s where my daddy met his second wife. Her name was Annie Wright. She already had two daughters. But I only lived with them for just a little while. I don’t know what happened to my sister (Elsie Mae) at that time. She was somewhere else. My daddy sent me to live with his daddy and stepmother in Lumberton (NC). The next time I saw my sister, she was visiting my daddy. I don’t know where she had been living, or anything. I was still living with my grandparents then.

JM: Did you keep up with Elsie Mae?

BE: Yes, but she would come and go. At one time, she surprised us. She walked in one morning and introduced us to her husband. She must have been about 21 then. I saw him that one time, and then he disappeared from the picture. But they had a son from that marriage. She eventually moved to Pueblo, Colorado, and I eventually wound up in Colorado Springs. When my sister passed away, nobody told me, and I had to read about it the newspaper. Their faith is different from ours. They severed contact with us with us after they became Jehovah’s Witnesses. My sister died January 11, 1993. She died in a nursing home of Alzheimer’s. She was born August 1, 1927.

JM: What happened to your father?

BE: Back in the 1950s, my father and his wife and her daughters came out to visit my sister in Pueblo, Colorado. He died in Pueblo on January 19, 1977, and is buried in a little town outside of Pueblo.

JM: Why did you move to Colorado?

BE: My husband and I started out as pen pals. I was 14 and he was 17. He lived in Oregon, and I lived in North Carolina. My sister had a pen pal, and she went to Pueblo (CO) to marry her pen pal. They were together until he passed away. In 1949, my husband, at age 18, met me in Pueblo, and he decided to stay. We got married December 31, 1949. We’ve been married a little over 60 years.

JM: Did you graduate from high school?

BE: No, but later on I got my GED and had a couple of years of college.

JM: How many children did you have?

BE: Four.

JM: Since your mother died when you were seven, I guess you might not have a lot of recollections of her.

BE: The memories are so vague. I remember going to some kind of little zoo with my parents and my sister. There was a big ostrich there. I wanted to feed it, but it snapped at my fingers and pulled some of the skin off. I am fascinated by ostriches, and it’s probably because of that little incident. I remember going to Dallas from Hillsboro. I saw the big Mobile Oil horse that used to be on top of the Magnolia Building. I remember going on the train. That was when the seats faced each other. That was the only time I saw my grandparents. I think the trip to Dallas was made sometime after she was diagnosed with leukemia. She wanted to see her parents one more time. Back then, leukemia was always terminal.

Some of my memories are bad. My daddy was a drinker. I believe that he was an alcoholic, because he was gone so much. But the last 20 years of my daddy’s life, he was very well liked. He quit drinking and became a devoted husband. He was married only 14 years to my mother. He was married to his second wife over 30 years.

I remember sitting on the porch with my mother and singing silly songs. One of the songs we used to sing was ‘Salty Dog.’ We lived in a house that was up on stilts, like a lot of houses in North Carolina, where the front is usually ground level, and the back is way up. There was a young boy that stayed with us for a while, and they called him Junior Lamb. I don’t know if he was one of her children from her first marriage, or just a cousin or something. But it’s strange that his last name was my mother’s first married name.

JM: What does it mean to suddenly see a picture of your mother as a little girl, when it’s been almost 70 years since she died?

BE: It’s like finding a missing part of my life. I remember her being a little chubby, not fat, just a little chubby, but she was so skinny in the picture. She was always happy as far as I remember, except when she and my father had problems. She was very well liked. Everywhere we went, she was always laughing. But the only three times I can remember being together as a family were the trip to Dallas, the trip to the zoo, and the trip to Virginia. I remember going to the cotton mill to see her. She liked to dip snuff, which a lot of people in the South did. She had her little can of it, and she would come out of the mill and dip it, and have a Pepsi. If a woman ever loved her children, that woman sure loved my sister and me. My mother nursed me until I was three years old. When she was at home, we were always right there with her. You know, she had lost so many children, that she was clinging to us.

She went to a hospital in Durham. I think it was Duke University Hospital. It was when they just started doing the bone marrow test. They did one on her breast bone. That’s another time I remember that my daddy was with me. She was describing how it hurt when they did that test. I think she even worked a little while after she became ill. She was a hard worker. She took Ironized Yeast tablets. She was tired all the time.

I think it’s great that her story can be told. She had such a terrible childhood. And then to have her life cut so short, at 41. Sometimes you say to yourself, ‘It’s not fair.’ But there’s a reason and purpose for everything. Now that I have that picture, it’s as if I can see her face right in front of me.

After this interview, I found many documents regarding Rosa’s family, and I mailed them to Beatrice. She responded:

“My daddy told so many fibs, I never knew what to believe. This is just amazing. You have found the whole family for me. It’s very emotional, learning all these things. My children never knew any of my mother’s side of the family. My dad was rather aloof. When my children were growing up, he couldn’t even remember their names.”

*Story published in 2010.