Lewis Hine caption: 7-year old Rosie. Regular oyster shucker. Her second year at it. Illiterate. Works all day. Shucks only a few pots a day. (Showing process) Varn & Platt Canning Co. Location: Bluffton, South Carolina, February 1913.

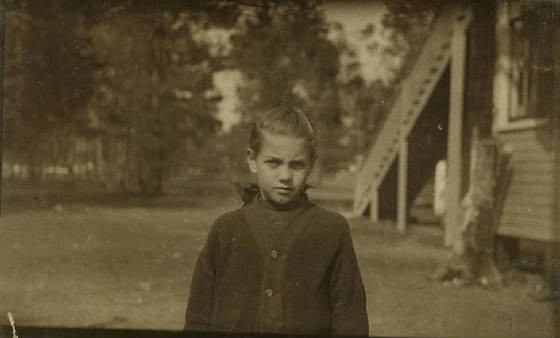

Lewis Hine caption: “Little Rosie (Berdich)” one of our former friends that I found in Bluffton 3 years ago. She has given up shucking, because her mother is afraid of the law, and is attending school regularly as long as they are in the south. Location: Bluffton, South Carolina / L.W. Hine, February 1916.

“She used to talk about when she was young and they traveled from Baltimore to South Carolina and back to pick fruits and vegetables. I know that she grew up in Baltimore. They were poor, and they lived in a tenement house. She never talked about going to school. We always wondered how she learned to read and write.” -Mary Agnes Taylor, daughter of Rose Berdych

Rose Berdych has the distinction of apparently being the only child laborer that Lewis Hine photographed, and then photographed again on a return visit. In my research so far, I have found (not surprisingly) only one case where a child laborer remembered being photographed by Hine; but one would think that Rose might have remembered Hine and his camera the second time he took her picture, only three years after their first encounter. But she never mentioned it to the descendants I interviewed.

The contrast between the two photos is striking. In the second photo, Rose is neat and clean, and nicely dressed for school. Hine says: “She has given up shucking, because her mother is afraid of the law, and is attending school regularly as long as they are in the south.” Could that mean that if and when the family returns to Baltimore, her mother will take Rose out of school again? On his two visits, Hine took a total of eight pictures of Rose.

The following is excerpted from the Sixth Annual Conference of the National Child Labor Committee, in January of 1910:

Dr. McKelway: Mr. Chairman, I paid a visit to Pass Christian, Miss., last spring. I had investigated the oyster canning industry in the Gulf States to some extent before. I was amazed at the number of small children who were employed in the oyster shucking factories. There are a good many along the Gulf coast, and some on the South Carolina coast. I found that the workers were Bohemian and Polish children from Baltimore. Our chief adversary in the fight for a better child labor law in Florida was the owner of an oyster cannery in Apalachicola. I visited his factory and saw acres of oyster shells there fifteen feet deep, and a great proportion of those oysters had been taken out of the shells by little children. We would not make any exemption in the Florida law, although we had to accept the twelve-year-age limit, and last year the proposal was made again that we could have the fourteen-year-age limit if we would exempt this oyster canning industry, which we declined to do.

Now here was a very interesting situation, that these people were brought from Baltimore and other parts of Maryland and Delaware in the winter season to shuck the oysters along the Gulf coast. Mr. Hine went to Maryland and made some investigations there, and he made a very interesting study of the situation and took a large number of photographs. The children in this oyster canning industry and fruit and vegetable canning industries are smaller than any children I ever saw in industrial work, smaller even than in the southern cotton mills. Miss Goldmark has spoken of the prejudice against these children and the difficulty of taking them into the schools. I found the same prejudice to exist in Florida, and the difficulty there is that they have had no compulsory school law, so the children have absolutely no schooling. The schools are not open in Maryland in the canning season, and then in the winter months the workers go to the Gulf coast.

Miss Anna Herkner: It is perfectly possible for a child to be born in Baltimore and grow up to the age of fourteen and never attend school. That is what is going on all the time. I want to make just a slight correction to something Dr. McKelway said. It is mostly Poles and not Bohemians who go south. Bohemians have done that in times past, but the public schools have had an Americanizing influence, so they have now reached the stage where they understand American institutions better. The first children – the first generation of those born here, who do not come under the influence of the public school, make the troublesome element in our community. The Poles in Baltimore are now at the stage where the Bohemians were twenty years ago. They work in canneries and on farms under such conditions as have been described. The child labor law in Maryland permits them to work in the cannery both in the country and in the city until the middle of October. It is usually November before they all get back, and about the end of November they begin going south. There are any number of families who do that, who have done that for years, and we have now children, many cases I know, who have never been to school.

The possibility of regulating the migration of people from one state to another was discussed, and Dr. McKelway suggested a license tax upon agents who go into a state to get laborers for other states. North Carolina and Tennessee have laws of this kind. He said, “If Maryland would pass a similar law, it would at least discourage this wholesale migration to the southern states.” The fact was brought out that many of the children work in Maryland canneries until the middle of October. Before the truant officer reaches them to compel attendance, they have gone south to work.

Lewis Hine caption: Rosie, (on the left) regular oyster shucker. A smaller one will be working soon. Varn and Platt Canning Co. Location: Bluffton, South Carolina, February 1913.

Lewis Hine caption: Housing conditions of the white workers in Varn & Platt Canning Co. Location: Bluffton, South Carolina, February 1913, Lewis Hine.

Lewis Hine caption: Varn & Platt Canning Co. Rosie & her doll. Location: Bluffton, South Carolina, February 1913, Lewis Hine.

After pouring through the many photographs that Hine took of Rose, I found her in the 1910 census. She was living in Bluffton, with her parents, listed as Mike and Marine, and three siblings. All of them worked in the oyster cannery except Rose and a two-year-old brother. In another 10 minutes, I found the family on a genealogy posting on Ancestry.com, which included contact information. So I emailed an inquiry and a link to the Library of Congress photos. A day later, I received this reply from Shana Taylor, Rose’s granddaughter.

“My family is amazed about the photos. We had no idea about them and had never even seen any pictures of my grandmother as a young child. The family resemblance to my mother, my aunt, my sister and myself is very strong.”

I interviewed Ms. Taylor, and her mother (Rose’s daughter), Mary Agnes Taylor.

Rose Dorothy Berdych was born in Baltimore, Maryland on July 29, 1905. She was the first of two children born to Michael Berdych and Mary Zarneski, who were married in 1904. It was Michael’s second marriage. His first marriage produced two children, but his wife died. He came to the US from Germany in 1891, landing in Baltimore. Second wife Mary was born in Austria, and came to the US in 1903.

According to the 1920 census, the family was living in Charleston, South Carolina, where Michael still worked in the oyster industry. Rose also worked in a cannery, but she and her 12-year-old brother were attending school, and both could read and write. Rose married James DeChriste about 1923, according to the 1930 census, although her daughter and granddaughter thinks they were married in Savannah, Georgia about 1921. They had five children.

Rose’s parents, Mary and Michael died in 1946 and 1947, respectively. They are buried in Baltimore. Her husband James died in 1969 at the age of 66. Rose died on February 2, 1990, at the age of 84.

Lewis Hine caption: 7-year old Rosie. Regular shucker. Her second year at it. Illiterate. Works all day. Shucks only a few pots a day. Varn & Platt Canning Co. Location: Bluffton, South Carolina, February 1913.

Edited interview with Mary Agnes Taylor (MT), daughter of Rose Berdych. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on May 26, 2011.

JM: What did you think of the photographs?

MT: I never had any pictures of my mother at that age. I can see a lot of resemblance to me, my siblings, my two grandchildren, and some of my sister’s children.

JM: What do you think about the fact that she was working as an oyster shucker at that young age?

MT: I couldn’t believe it. I knew that her family were migrant laborers, but I had no idea she worked at that age. She used to talk about when she was young and they traveled from Baltimore to South Carolina and back to pick fruits and vegetables. But she never talked much about her childhood. I know that she grew up in Baltimore. They were poor, and they lived in a tenement house. She never talked about going to school. We always wondered how she learned to read and write.

JM: When were you born?

MT: 1941.

JM: How many children did your mother have?

MT: Five. I’m the youngest. The others were 12, 14, 16 and 18 years older than I am.

JM: When you were born, where was your family living?

MT: On Yonges Island, in South Carolina.

JM: What was your father doing for a living then?

MT: He was working as a pipe fitter at a private shipyard in Charleston.

JM: Did your mother work when your siblings were growing up?

MT: No.

JM: Did you know her parents?

MT: I was only five years old when they passed away in Baltimore. I can remember going to Baltimore on the train with my mother when my grandmother died. Her name was Mary. And then two weeks later, I went back with both my parents when my grandfather died. His name was Michael. He didn’t speak English, and neither did my grandmother. My mother told me that her father came from Germany with two small children, after his first wife died. Then he married my grandmother.

JM: The 1910 census listed your grandmother as Polish, from Austria-Poland.

MT: She said she was from Austria-Hungary.

JM: The census listed four children, including your mother. There was Adam, and two older children, who were probably from the first wife. Adam was the only one not born in Baltimore.

MT: Right. The two older ones were Joseph and Anna. They were born in Germany.

JM: When did your mother and father get married?

MT: I don’t know the year, but she was pretty young. It was probably about 1921. My father’s family came from Portugal. My mother said that when she came to South Carolina, she could speak six languages: English, Polish, German, Russian, Portuguese, and I can’t remember the other. I remember her speaking Polish. She had a friend whose husband ran an oyster factory on Edisto Island. They used to visit, and they would speak Polish the whole time.

JM: Did your father always work as a pipe fitter?

MT: He did that for a while, and then he bought a dairy farm and ran it for a number of years. I grew up on the dairy farm. We moved there right after my grandparents died. It was on Yonges Island. He had a stroke when he was about 62. We had to stop farming, but he kept the farmland.

JM: When did your father die?

MT: 1969.

JM: What was your mother like?

MT: She was always at home. She liked to cook, and she liked to bake, and she always had baked goods like cakes and pies. She kept a clean house. She grew beautiful flowers in her garden. She was quiet and reserved. My mother had a lot of friends through the church. My father was Catholic, but even so, he joined the Masons, because all his friends were Protestants. My mother was a very devout Catholic. She said the Rosary every day.

JM: After your father died, how did your mother get by financially?

MT: She sold the property, and she was getting my father’s Social Security. She was doing well. She didn’t want for anything.

JM: In the last years of her life, where did she live?

MT: With me, in Charleston. She didn’t really know anybody in Charleston. Sometimes we would visit my father’s cousins, who lived in Mt. Pleasant. She went to church a lot, and she went shopping.

JM: When you were growing up, is there something special you liked to do with your mother?

MT: She was always busy. She took care of the house and cooked three meals a day, while my father and my brothers ran the dairy farm. If there were events at the school, she would always go.

JM: How far did you get in school?

MT: I had two years of college. I studied nursing, but I didn’t finish, because I got married. That was in 1965. I worked for a local pediatrician until I had my first child.

JM: Did any of your siblings graduate from college?

MT: One of my sisters did. She became a registered nurse.

JM: Did your mother ever go back to Baltimore after her parents died?

MT: Yes. She would go and visit her half-brother, Joseph. Her younger brother Adam lived with him. She also visited my father’s mother there.

JM: What do you miss most about her?

MT: Her cooking. She was a wonderful cook. She made great fried chicken. She made the best meat loaf I’ve ever tasted. And she made vegetable soup and oyster stew. She talked about things that she used to cook, but I never had any of it. It was Polish food, like duck blood soup and stuff like that.

Edited interview with Shana Taylor (ST), granddaughter of Rose Berdych. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on June 23, 2011.

JM: Did you have any idea that your grandmother would have been working in a situation like this at that age?

ST: I knew the family were laborers and worked in oyster factories, but I never knew she did it. She never talked about that. It makes me sad to see what kind of conditions they were living in.

JM: You knew her for about 17 years. Did you see her a lot?

ST: We went to her house every Sunday for dinner. When I was in third grade, about 1983, she moved in with us, and she lived with us until she died.

JM: What was she like?

ST: She was very loving. When we went to her house, she was always cooking. When she was living with us, she would sit in our den and watch soap operas. At night, we would all gather in her room and watch TV with her. She taught me how to cook, which is funny, because my mother and aunt said she never let them in the kitchen or taught them how to cook. She taught me how to cook some things that my mother doesn’t know how to cook.

JM: What are some of the things she taught you how to cook?

ST: Making chicken and dumplings and baking cakes, like her secret recipe pound cake. It’s funny that I can make perfect dumplings, but my mother always has problems with it.

JM: Did she ever talk about Baltimore?

ST: She told us that in the mornings, the Polish men would go down to the corner with little pots and fill them with beer and sit on the porch steps and drink it. She used to go down to the bakery to get some kind of a special crumb cake. They didn’t have an indoor toilet, so they had to use an outhouse in the alley. She said that her mother was terrified of the rag man who would come around in a wagon. And when the Gypsies would come into the city, her mother wouldn’t let her outside because she said the Gypsies would steal children. She told us that she remembered when the Titanic sank, and that she remembered seeing the boys on the street selling newspapers that had headlines about the Titanic.

JM: Do you know how she met her husband?

ST: She told us that they met on a train going to Baltimore from Charleston. She also told us that her father came from Germany. His wife had died, and he came over to Baltimore with two young children. Her first child was born in 1923. She took the train to Baltimore to be with her mother when the baby was born.

JM: What was your grandfather like?

ST: I didn’t know him, but I was told that his family also worked in the oyster factories. He was the oldest of six children. He was born in Thunderbolt, Georgia. His family lived in Baltimore also. He lied about his age to join the Navy. He had many occupations. He was a pipe fitter, he drove a gas truck at one time, and then he ran a dairy farm. He died of emphysema that he apparently got from breathing in the pipe dust.

JM: Was your grandmother in good health the last few years of her life?

ST: She was ill. She had dementia. She was bedridden for about six months before she passed away. She would talk to my grandfather constantly, like he was sitting right next to her. But he had been dead since 1969. It was hard on me, and on the whole family. My grandmother lived right next to the Catholic Church. She had all these prayer cards that she collected from the funerals, and now I have them. And I found all these recipes she had clipped out of the newspapers, but I don’t remember her ever using any of them. I kept her apron, and I used to wear it whenever I cooked. I did that until it completely fell apart. It’s packed away now.

Rose Berdych: 1905 – 1990

“Sammy is Rose’s great-grandson. My older brother, Wayne Taylor, is his father. When my family was looking at the pictures of Rose, my father asked who looks like Granny, referring to the picture of Rose shucking oysters. I immediately brought over the picture of Sammy, which was sitting on a table in the den. They have the same expression….that mischievous, shy look. Sammy is now six years old and still uses the same facial expression.” -Shana Taylor

*Story published in 2011.