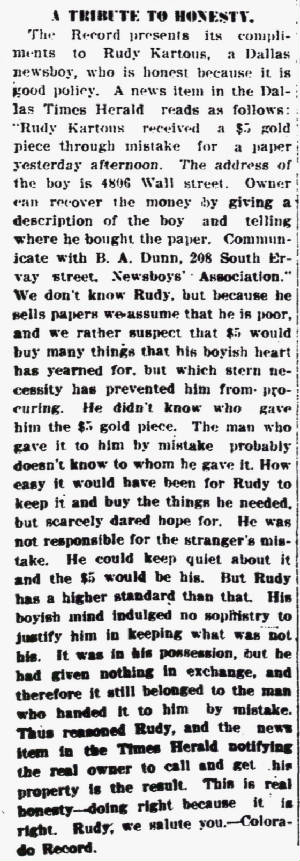

Lewis Hine caption: Seven year old Rudie Kartis, and brother, Louis, 9 years old. The older brother soon finds little one is a drawing card. Location: Dallas, Texas, October 1913.

Rudoph Kartous mentioned article below.

“The Newsboys of Dallas,” from The Survey, Vol. XLVI, April 1921 – September 1921

When plastic, immature boyhood is caught in the whirlwind cylinder of the city, what happens to the boy? It was to answer that question and others that an exhaustive study has just been completed by the Civic Federation of Dallas of the newsboy life of that city. What effect does Streetland, the only geography many youngsters know from personal experience, have upon the boy? What are its deltas, its islands and its promontories? What part does the street gang with its psychology of the pack and claw play? What result does the street-trading with its sharp wisdom have upon boy life?

An investigation was undertaken under the direction of Eva Freeman of the Department of Public Welfare by forty-two senior sociology students at the Southern Methodist University. Comer M. Woodward, professor of sociology at the university, J. F. Kimball, superintendent of the Dallas Public Schools, principals, teachers and probation officers actively cooperated. The primary sources of information used were the Street and Newsboys Club, the school, the family, the boy himself, the neighborhood juvenile court and the employer. Supplementary sources, such as the minister, playground leaders, and others were also drawn upon. The survey itself was preceded by a collection of data by the federation dealing with delinquent and under-privileged children whose records were available in the juvenile court, the police department, the county jail, and the newsboys club.

Although there are no ordinances in Dallas restricting newspaper sales to boys, the newsboys club with the assistance of the mayor and the county judge seeks to restrict such sales to boys over ten years of age. It is estimated by W. A. Tischang, superintendent of the newsboys club, however, that there is an average of six boys from six to nine years of age constantly on the streets as newsboys. He has learned that a girl is rarely found selling papers on the streets. The casual newsboy recruited from the submerged migratory group- in and out of Dallas-here a week and gone, camping on the outskirts; children of junkers and horse traders-from families that pick cotton in the summer and fall, drift to Dallas for three months in the winter and are in Arkansas, Oklahoma or South Texas in the spring-was not considered so much as the more permanent group.

Much of the popular conception concerning children in the newspaper business is exploded by the facts brought out. The public has taken the tolerant attitude that the average newsboy is making a valiant effort to support a widowed mother and starving brothers and sisters, that the life of the newsboy is a wholesome one, and that his activity helps to equip him for a future successful business career. “The homeless newsboy of Dallas is a myth,” states the report. It was ascertained that in the case of only one newsboy out of 263 were both parents dead, and it was also found that even that boy was living with relatives. However, in nearly one-third of the cases one parent was dead or there was a divorce or a separation. The thread-bare argument that newsboys contribute materially to the budget of their families was effectively dispelled so far as the newsboys of Dallas are concerned. An estimate of the actual earnings of the 249 boys who were engaged in the street sale of papers during a six-month period averages $3.15 a week for each boy. So far as the investigators could discover, only about 37 per cent of the boys contribute in any way to the support of their families.

Unfortunately, the relation between the very high percentage of separation and divorce in the families of these boys and delinquency and school standing of this group is not as clearly indicated as it might have been. For example, “out of inadequate records and with consequent incompleteness, 49 out of 303 investigations revealed delinquency with juvenile court action.” If this ratio were to prevail, “it would bring 1,840 Dallas boys before the juvenile court each year (instead of 675 now prevailing). In other words, the newsboys of Dallas contributed two and three-fourths times the percentage to the delinquency as prevails in the boy population as a whole.” As regards their school standing, since seven years is the age at which children enter school in Dallas, the results secured were more favorable than would be the case in many cities. With the assistance of the public school officials, statistics were compiled as to the standing of 267 boys. Eighty-five of this number had a total of 161 transfers, “indicating an instability of local residence which is not conducive to habits of good citizenship.” In over 50 per cent of the cases, attendance was either irregular or infrequent or some form of truancy was present. Furthermore, 143 of these boys repeated their grades, as disturbing a factor as the irregularity of attendance.

An enlightening section of the report deals with the leisure time and other activities of the group. It is interesting to note their favorite reading: 89 indicated a preference for stories of adventure, 28 for fairy tales, 27 for articles about boy scouts, 18 for history, one for war. The motion picture plays an undue part in the lives of the Dallas newsboys. It was estimated that 222 boys attended 475 times a week. If this same average were maintained by the 132,000 adults and children of Dallas over 10 years of age and the average admission were twenty cents, this one amusement bill would reach the enormous sum of $2,900,000 annually, or an amount reaching well toward the cost of the entire municipal government.

A number of vivid pen-pictures presents a cross-section of the Dallas street boy. There is, for instance, the prepossessing youngster of fourteen who can “lick anybody in school,” and the boy who is a natural leader but is confronted with very serious environmental and home conditions. In commenting upon these stories the report states that “the boy-the Dallas boy-newsboy or millionaire’s son, is the one great raw material of the whole world. If he is already bad, society does an evil thing to posterity if it contributes to his further delinquency.”

Lewis Hine caption: One of Dallas’ little newsboys. Location: Dallas, Texas, October 1913.

In 1908, the Kartous family, Anton (or Antone), Fannie (or Frances), and their five children, sailed from Eastern Europe to Galveston, Texas, and went to live in Dallas. Antone, called Tony, went to work as a moulder in a foundry. In a few short years, the family had two more children, and Rudy and Louis were selling newspapers on city streets.

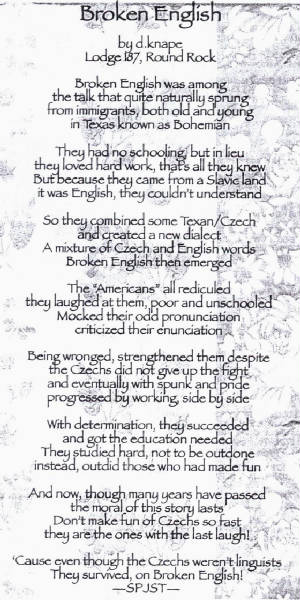

They were among what was at the time the third largest immigrant group in Texas, technically natives of Austria, mostly Moravians who spoke Czech. Immigration officials often incorrectly referred to them as Bohemians. In 1920, the country of Czechoslovakia was established. According to the Texas Almanac, the Czech language is still widely spoken in Texas. More than 150 years ago, Czechs in Texas established schools and newspapers to teach and maintain their language. Today, the University of Texas at Austin teaches Czech as a modern language. Czech culture, such as food and music, are represented in many popular festivals in Texas.

According to the 1910 census, the Kartous family was living at 470 South Lamar Street, which is in the heart of downtown Dallas, now near the historic district and the Dallas Convention Center. In the 1920 census, they were living in their own home at 2806 Wall Street, less than a mile from their first address. In the 1930 census, Rudy was still single and living with his parents at the same address, and his occupation was listed as a typewriter repairman. Louis was living in 1930 at 2703 North Fitzhugh St, with his wife, Emily, and two children. He was working as a machinist in an iron works. Louis had married Emily Takats in 1928. Rudy married Lydia Hemzal on April 28, 1934. Their father, Anton, died in 1956, at the age of 80; their mother, Fannie, died in 1940, at the age of 66.

Louis Kartous passed away in Dallas on March 5, 1978, at the age of 73. His wife Emily had passed away six years earlier. Rudy passed away in Dallas on December 30, 1989, at the age of 83. His wife Lydia passed away in 2002. I interviewed Rudy’s daughter, Jeanne, and Louis’ two children, Louis and Emily. None of the children knew about the Hine photos.

**************************

Edited interview with Jeanne Hall, daughter of Rudolph Kartous (the younger of the two boys). Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on June 8, 2010.

JM: When were you born?

Jeanne: I was born March 3, 1941, at Florence Nightingale Hospital in Dallas, which was then part of what is now Baylor Hospital. I was an only child.

JM: Where were your parents living at that time?

Jeanne: In a house on Llano Avenue. My mother’s parents owned it. It was a duplex, and they lived next door.

JM: When did your parents marry?

Jeanne: April 28, 1934. They were married in Dallas at the Cathedral Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, formerly Sacred Heart Cathedral.

JM: What was your mother’s maiden name?

Jeanne: Lydia Hemzal. She was Czech also.

JM: Did you know your father’s parents?

Jeanne: I never knew his mother at all. I knew his dad, Antone Kartous. He lived a couple of blocks away in a garage apartment behind his son Tony’s home.

JM: Do you know when the family came over from Czechoslovakia?

Jeanne: No, but I know they came through Galveston.

JM: Did your father speak Czech?

Jeanne: My mother’s parents, who lived next door to us, spoke Czech all the time. They spoke a little broken English, but they spoke to me in Czech. Therefore, I know the language and can speak it. My parents spoke to them in Czech, but they spoke English to me.

JM: Were there a lot of Czech customs that your parents practiced?

Jeanne: No, not really. My grandmother was a wonderful Czech cook, and my mother did that a little bit. She went to the Catholic Church up until when I was about four years old, and then she changed over to the Baptist Church, and then I was baptized a Baptist. For some reason, my father became an Episcopalian. His oldest brother, Tony, was also an Episcopalian.

JM: What was your father doing for a living when you were growing up?

Jeanne: He was in the typewriter business. He worked for S.L. Ewing. He went to office buildings and serviced typewriters, adding machines, etc.

JM: How did he acquire that skill?

Jeanne: I have no idea. I do know that his older brother, Tony, owned an office supply company.

JM: How long did your father continue to work as a typewriter repairman?

Jeanne: All his life, until he retired.

JM: Did your mother also work?

Jeanne: She worked part time when I was in high school, but she was mostly a stay-at-home mom.

JM: Did both of your parents graduate from high school?

Jeanne: My daddy graduated from Forest Avenue High School, and my mother graduated from North Dallas High School, and then went to a business college.

JM: Did you get married?

Jeanne: Yes, in 1960.

JM: Did you stay in Dallas?

Jeanne: I’ve been in Dallas all my life.

JM: Do you have any children?

Jeanne: I had one son by my first marriage, and another son by a second marriage.

JM: What was your reaction when you saw the photos?

Jeanne: I thought they were very interesting. I was kind of shocked. I knew that he and his brother were paperboys. And I knew that the brothers seemed to have kept in contact with other boys that sold newspapers.

JM: Did he ever tell you anything about being a newsboy?

Jeanne: No, he didn’t talk much about the past.

JM: Have your children seen the photos?

Jeanne: Yes, and they couldn’t believe it either.

JM: When did your mother die?

Jeanne: In 2002.

JM: Was your father in pretty good health in his last years?

Jeanne: Yes, I guess so. He was a diabetic. He had a heart attack in December of 1989, and that’s what he died of. At that time, my parents lived on Sudbury Drive, in Dallas. They owned the house.

JM: What was your father like?

Jeanne: He had a lot of friends. He played dominoes and poker a lot with his friends. He and my mother square danced a lot. And my parents would go to the Czech lodges. We used to go on fishing trips with some of his friends. We would have cookouts and fish fries. My daddy loved to go to the horse races. He used to go to the races in Hot Springs (Arkansas) with his brother Joe and friends. My dad was a very likeable person.

Rudolph Kartous: 1906 – 1989

Edited interview with Louis Kartous Jr. (LK), son of Louis Kartous (the older of the two boys). Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on June 29, 2010.

JM: What did you think of the photos of your father and your uncle?

LK: My dad told me that he sold newspapers, but I’m surprised that he was photographed doing it. He told me about a newsboy club that they had when he was a kid. I think it was on Commerce Street. I think those pictures were taken in front of the courthouse in Dallas. I recognize those cinder blocks. They were wearing immigrant clothing, that’s for sure. My father was born in the Czech Republic. They came from a town called Brno. He came over with his family in 1908. The only language I spoke when I was young was Czech. I learned English from the other kids, but I spoke Czech at home.

JM: How far did your father get in school?

LK: I’m not sure. I know that he went to Forest Avenue High School.

JM: When were you born?

LK: I was born in Dallas in 1930.

JM: What was your father doing for a living at that time?

LK: I think he was working for his uncle, who owned the Dallas Iron Works. He was an ornamental iron worker. He was forging and welding mostly.

JM: Where were you living then?

LK: On North Fitzhugh Street. We rented a single-family house.

JM: Did you grow up in that house?

LK: No. He had a few different jobs, and we moved a few times. He never owned a house. He always worked for the person who would pay him the most money. He belonged to the union at one time, but he finally got perturbed with them and quit the union.

JM: How many years did he do that kind of work?

LK: All his life, until he retired and got on Social Security.

JM: What was your mother’s name?

LK: Emily. She was a country girl, one of 12 children. They were sharecroppers. She was Czech, too. Her last name was Takats. She was living in Ennis. My father would drive down there every Saturday night to go to the dance. That’s how he met her.

JM: When did they get married?

LK: I want to say in ’24, or maybe ’26. (It was in 1928.)

JM: How many children did they have?

LK: Two boys and a girl: me, Edward and Emily. My brother died in 1979. My sister is still living.

JM: Did your mother work?

LK: She was a stay-at-home mom.

JM: Did you finish high school?

LK: No. Neither did my brother and sister. I just didn’t get along in school. I went to a country high school, south of Dallas. The first year there, I had to deal with an initiation. They sure sent me through the gauntlet. They made me carry cow manure in my pockets all day long.

JM: What kind of work have you done?

LK: In my early years, I was in the office machine business, as a technician. That was in the mechanical era. When they switched to electronics, I was forced to get another trade, so I went to trade school and learned to rebuild alternators and starters, and then worked for a company in Houston that did that. I was also in the Korean War.

JM: Do you have any children?

LK: One daughter.

JM: What was your father like?

LK: Let me put it this way. When I was a sophomore in high school, I sat down with him one day and said, ‘Dad, I’m not getting nothing out of school, so I’m gonna quit and go to work.’ And he says, ‘Fine. I’m gonna see that you go to work. While you’re living here, you’re gonna pay room and board.’ And that’s what I did.

JM: What did you think about that?

LK: Well, I never thought about it much then, but after all these years, it seems kind of comical to me.

JM: Maybe it was a good lesson.

LK: Well, I’ve been working ever since. At lot of times, I worked two jobs.

JM: When you were growing up, were there things that you liked to do with your father?

LK: My father wasn’t the kind to do that.

JM: What did he like to do when he wasn’t working?

LK: He had a drinking problem. He worked hard and he drank hard.

JM: Did your father belong to any Czech organizations?

LK: He belonged to Sokol. It was an athletic club. And another called SPJST (Slavonic Benevolent Order of the State of Texas).

JM: What else did your father like to do?

LK: He liked to go bet on the ponies. He got me started on it.

JM: Were your father and his brother Rudy close?

LK: No. My father wasn’t close with the family at all. He was sort of the black sheep of the family.

JM: When did your parents die?

LK: My mother died in 1972, and my father died in 1978.

JM: Where was your father living when he died?

LK: On Phillips Street, by himself. At that time, I was living in Pasadena, a suburb of Houston. After my mother died, he was trying to find a mail-order bride. He had a picture made, and he was going to send it, but he never did, and I wound up with it.

**************************

The following are excerpts from my interview with Emily Branum, daughter of Louis Kartous. Interview conducted September 28, 2010.

“It was a special treat and surprise to get the pictures, for me and for my daughters and granddaughters. We knew that he sold newspapers when he was a boy, because he told us, but to get the pictures of him doing it was something else. Dad served a short stint in the Merchant Marine when he was about 21 years old. Before he got married, he traveled on the trains as a hobo for a while. He went wherever he thought he could find work. That was pretty common back in those days, and the people who lived along the railroad lines in the towns would feed them if they came to the door for a handout.”

“I was born in 1928. My mother was from the country. Her dad was a farmer. But Dad’s folks settled in Dallas and stayed in the city. They lived on Lamar Street, not far from downtown Dallas. I was 10 when Grandma Kartous died, and I was about 23 when my Grandpa Kartous died.”

“My father was always in our lives. After Mom died, we tried to stay close with him. At one point, my husband was traveling, because of his job, and Dad came to join us in New Orleans for a while. He was not feeling well, and didn’t like being alone. He was kind of distant as a father, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t care about us. He was just not the kind to be involved a lot with his children. We were poor, like so many families back then, but our family unit always stayed together, and that’s the important thing.”

Louis Joseph Kartous: 1904 – 1978

Epilogue

The day after I posted this story, a short article in the Dallas Observer mentioned it. And then I got this email:

“I’ve just finished reading your story and am close to tears. My father, William Proza, grew up with the Kartous boys, and they were good friends throughout his life. His foster parents lived and had a grocery store at the corner where Wall Street meets Lamar Street. I didn’t recognize the Kartous boys’ first names, but when Rudolph was identified as ‘Doc,’ I thought, ‘Of course, Doc Kartous.’ I remember my mother mentioning him as a close friend when my dad was alive. My dad was also a typewriter repairman and worked for Rudolph’s brother Tony, as front-end manager at Ames Supply Company, which sold typewriter parts. According to my mother, there was a brother nicknamed ‘Cotton,’ because he had white-blond hair. Do you know if that was Louis? Cotton had woodworking skills, because I have three pieces that he made for my parents, possibly as wedding presents. I lost contact with the Kartous family when my dad died in the late 1950s.” -daughter of William Proza

I called Louis Kartous Jr., and he told me that he remembered William Proza, and that “Cotton” was his father’s youngest brother, Joe. So I passed that along to William’s daughter.

*Story published in 2010.