Lewis Hine caption: Mrs. Finkelstein, 127 Monroe St. Bessie (age 13), Sophie (age 7). Girls attend school. Making garters for Liberty Garter works, 413 Broadway. Mother, a widow, earns 75 cents a day by working all day until 12 at night. Bessie works until 10 P.M. Sophie until 9 P.M. They expected to work until 10 P.M. to finish the job, although they did not know when more work would come in. Witness Mrs. Hosford. Location: New York, New York (State), January 1908.

In January of 1908, in New York City, Lewis Hine took what appears to be his first four pictures for the National Child Labor Committee, documenting what he called “home work,” a situation he would revisit many times in the city. The empathetic human qualities of Hine’s picture reflect the style of his celebrated 1905 pictures of immigrants landing at Ellis Island. But his caption lets us know that this family is facing a daily struggle to survive, their fate tied to the whims of the garment industry. Liberty Garter Works, the company for which the Finkelstein family worked, was owned and operated by Morris Mayper and his family. Like the Finkelsteins, they were Jewish immigrants from Russia. According to an article in the New York Times, the company filed for bankruptcy in 1911.

The following was published in the January 1907 edition of Cosmopolitan Magazine, one year before Lewis Hine photographed Yetta Finkelstein and her daughters.

Long before Hannah made a coat for little Samuel, women sat in the home at garment-making. The sweated sewing in the tenement home today is only a belated following of this custom of the ages. But the leisurely sewing of the old times was far away from the nerve-racking work of our hurried age. The slow ways are gone.

In unaired rooms, mothers and fathers sew by day and night. Those in the home sweatshop must work cheaper than those in the factory sweatshops if they would drain work from the factory, which has already skimmed the wage down to a miserable pittance.

And the children are called in from play to drive and drudge beside their elders. The load falls upon the ones least able to bear it—upon the backs of the little children at the base of the labor pyramid.

All the year in New York and in other cities you may watch children radiating to and from such pitiful homes. Nearly an hour on the East Side of New York City you can see them—pallid boy or spindling girl—their faces dulled, their backs bent under the heavy load of garments piled on head and shoulders, the muscles of the whole frame in a long strain. The boy always has bow-legs and walks with feet apart and wobbling. Here, obviously, is a hoe-man in the making.

Once at home with the sewing, the little worker sits close to the inadequate window, struggling with snarls of thread, or shoving the needle through unwieldy cloth. Even if by happy chance the small worker goes to school, the sewing which he puts down at the last moment in the morning waits for his return.

Never again should one complain of buttons hanging by a thread; for tiny tortured fingers have doubtless done their little ineffectual best. As for the lifting of burdens, this giving of youth and strength, this sacrifice of all that should make childhood radiant, a child may add to the family purse from 50 cents to $1.50 a week.

In the rush times of the year, preparing for the changes of seasons or for the great “white sales,” there are no idle fingers in the sweatshops. A little child of “seven times one” can be very useful in threading needles, in cutting the loose threads at the ends of seams, and in pulling out bastings. To be sure, the sewer is docked for any threads left on, or for any stitch broken by the little bungling fingers. The light is not good, but baby eyes must “look sharp.”

Besides work at sewing, there is another industry for little girls in grim tenements. The mother must be busy at her sewing; or perhaps she is away from dark to dark at office cleaning. A little daughter, therefore, must assume the work and care of the family. She becomes the “little mother,” washing, scrubbing, cooking.

In New York City alone, 60,000 children are shut up in the home sweatshops. This is a conservative estimate, based upon a recent investigation of the Lower East Side of Manhattan Island, south of 14th St., and east of the Bowery. Many of this immense host will never sit on a school bench.

Is it not a cruel civilization that allows little hearts and little shoulders to strain under these grown-up responsibilities, while in the same city, a pet cur is jeweled and pampered and aired on a fine lady’s velvet lap on the beautiful boulevards?

In 2014 (three years ago) I saw this photograph of the Finkelsteins and started searching right away for information about the family. After more than two months of research, I found considerable information, but what I did not find were any living descendants, not a single one. Below is what I found at that time.

I saw the Finkelsteins in the 1900 census. Husband and wife Samuel and Yetta were living at 186 Henry Street (Lower East Side), with five children: Moses, Ida, Annie, Isador and Rose. Bessie (who was in the 1908 photo) was not listed, but I presumed that was probably a census error. Samuel was a tailor. According to a variety of government records, Shmuel (Samuel) David Finkelstein and Yetta Feinstein married in New York City on December 28, 1891, after coming separately to the US from Russia in about 1887 or 1888. Their first child was born in 1891.

On August 22, 1904, Samuel died of consumption in Denver, Colorado (I found the death record online). I guessed that he may have been working for the railroad or the mining industry, and sending money back home. He was buried at Rose Hill, a Jewish cemetery in Commerce City, Colorado.

By 1905 (the State of New York Census is online for 1905, 1915 and 1925), Yetta, now a widow, was living at 127 Monroe Street (the address given in Hine’s caption), very near the future site of the Manhattan Bridge. In the 1960s, the tenement building and much of the neighborhood was demolished, and a public housing development called Rutgers Houses was built. Yetta had seven children in the home: Moses, Betty (probably Bessie), Annie, Isidor, Rose, Sophie and Henry. All attended school except young Sophie (also in Hine photo) and three-year-old Henry.

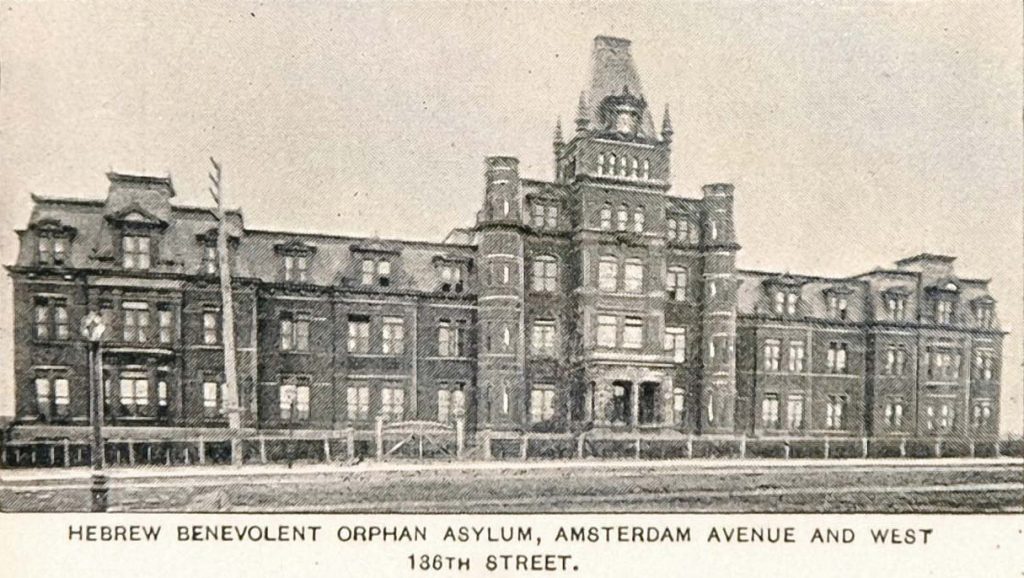

Then I stumbled upon a disturbing fact: some of the children appeared in the records of New York Hebrew Orphan Asylum. In December of 1904, Yetta placed Rose, Annie and Moses in the asylum. She applied to place Bessie in the asylum, but records indicate that Yetta did not follow through. Four years later, she placed Isidor in the asylum. Rose stayed for 10 years, Annie for six, Moses for five, and Isidor for four. All returned home upon discharge.

I found out that the Asylum served struggling Jewish families, usually those with a widowed parent who could not support the children for periods of time. Few children were adopted; most returned home. Girls were taught domestic skills, while boys were taught shoemaking and printing. It was located at the corner of Amsterdam Avenue and West 136th Street.

In 1910, two years after Hine photographed her, Yetta had four children living with her at a new address: 55 Rutgers Street, only a few blocks from their former apartment at 127 Monroe Street. The four were Moses, Bessie, Sophie and Henry. The census was enumerated in April, so Anna would return to the home three months later. Yetta worked at home for the garment industry and Moses was a silver plater.

In 1915, they are back at 127 Monroe Street, but likely at a different apartment. Yetta was apparently not employed, Moses (now listed as Morris) was a diamond polisher, Bessie (incorrectly listed as Betta) was a colorer (most likely a cloth colorer), Annie was a bookkeeper, Isidor was a cloak cutter; and Rose, Sophie and Henry were attending school.

In 1920, at the same address, Yetta was unemployed, Morris (or Moses) was a plater for a jeweler, Bessie was a sales clerk in a cigar store, Irving (probably formerly called Isidor) was a cloth cutter, and so was Henry.

In 1925, still at 127 Monroe, Yetta was a homemaker, Morris (obviously the boy previously called Moses) worked in a factory, Bessie was still at the cigar store, Irving was a still cloth cutter, Sophie worked for a curtain store, and Henry was unemployed. A daughter named Ruth, born in 1903, was listed, although no child by that name had been listed in any previous censuses, leaving me to believe that she was the girl previously listed at Rose.

In 1930, the family was living at 819 W. 180th Street, near the site of the George Washington Bridge, which was being built at the time. Yetta was unemployed. Bessie was a sales clerk, and so were Ruth and Sylvia (probably formerly called Sophie). Henry was a printer. Up to this point, none of the children listed as living with Yetta were married. But I couldn’t find Yetta’s other children in the census.

In the 1940 census, Yetta, unemployed, was still living at 819 W. 180th, with Bessie (sales clerk), Ruth (designer) and Sylvia (hotel worker). Living in an apartment right next to Yetta was son Henry, still a printer. He lived with his wife Ruth, and two children, Daniel (5) and Alan (1). Henry was listed as a high school graduate.

I was unable to locate a death record for Henry, or his wife Ruth, or their two sons. Assuming the sons could be still alive, I searched public records but could not locate them. I could find no death records for any of the Yetta’s other children, or for Yetta. The most common sources for death records are the Social Security Death Index, and state death records, sometimes posted online. I noted that some of the children might have died before acquiring a Social Security number; thus they would not have been listed in the Social Security Death Index. For the most part, New York State death records are not available online to the public. And in order to find death records for the daughters, I needed to know who they married (if they did), in order to know what their last names were when they died.

At that point, my research ended. So I posted the Hine photo and my abbreviated story on my website, and asked people to contact me if they were related to the family, or otherwise had more information.

On August 19, 2016, I received this surprise email:

“Our names are Eve and David, and Yetta was our great-grandmother. Her daughter Anna was our mother’s mother, our grandmother. We recently found your article and we desire to find out more information on the family. Hope to hear back from you.”

We talked on the phone soon after and I asked them how they happened to connect with me.

David: We’ve known about the Lewis Hine picture for quite a while. In fact, a copy of the picture hangs in our father’s apartment.

Eve: When I was in elementary school, I was watching a film, and the picture was in the film.

Joe: What was the film called?

David: I don’t remember. I saw it in a social studies class. The teacher used to talk about the trade unions, and I think it had to do with the garment workers association.

Joe: How did the picture lead you to me?

Eve: If you Google the picture with the caption, which we do often, your story about the picture comes up.

David: When we first saw your story, our mother was very sick at the time, so we didn’t follow up. But recently, we were curious about our grandmother Anna, who was in the orphan asylum. We wanted to find out what years she was there. We read your story again and it had some information about that, so we contacted you.

After a lengthy conversation, I knew I was going to learn much more from them than they would from me.

I interviewed them several weeks later, and again in December 2016. Over the next six months, they sent me family photos of Yetta, Bessie and Sylvia. And they also sent me copies of two astonishing letters, one written by Yetta, and one by Henry.

At one point, I located Daniel and Alan Finke, the sons of Yetta’s youngest child Henry Finkelstein (who changed his last name to Finke). They also gave me some valuable information.

Finally, just as I was about to finish the story, Daniel referred me to Richard Kelstein, grandson of Yetta’s son Morris. (Richard’s father Sidney had shortened the family name to simply Kelstein.) Richard referred me to his sister Madelyn Campbell, who provided further information, including a crucial piece of evidence for the story. With the new information, I was able to expand my research and piece together the dramatic story of this courageous family.

**************************

The following is the text of an unsigned letter written by Yetta Finkelstein, and published in 1906 in the “Bintel Brief,” an advice column in the Jewish Daily Forward. The full letter was included in the book Sixty Years of Letters from the Lower East Side to the Jewish Daily Forward. The book was published in 1990, and edited by Isaac Metzger. A copy of the letter was sent to me by Eve Bernstein and David Belkin.

Dear Editor,

Since I have been a Forward reader from the early days, I hope you will allow me to unburden my heart in the “Bintel Brief.”

Nineteen years ago, when I was a child, I came to America. Later I was married there. I was never rich financially, but wealthy in love. I loved my husband more than anything else in the world. We had seven children, the oldest is now thirteen. But God did not want us to be happy, and after years of hard work, my husband developed consumption.

When does a working man go to Colorado? When he has one foot in the grave.

When I began to talk to my husband about his going to Colorado, he answered that he couldn’t leave me alone with the children, and he kept working till he collapsed. When I was pregnant with my seventh child, I finally sent him away.

As time went on, he wrote me that he was feeling better, and no one was as happy as I. I counted the minutes till I could be with my husband again. Meanwhile, I had a baby and had to make bris alone. When my baby was three months old, I took my seven children and went to my husband.

My husband told me he had opened a small business in Colorado, and hoped to make a living. But I heard him cough, and when I questioned him, he answered with a bitter smile that there was no cure for his illness. I immediately saw my tragedy and wouldn’t let him work. I went out peddling with a basket, and left him at home with the children. I tried to make a living, I got a little aid, but my husband became gradually weaker.

For about fourteen months my husband didn’t leave his bed. I was willing to do the hardest work to keep him alive. I fought my bitter lot like a lion, to chase the angel of death from my husband, but alas, he won. With my husband’s death my spirit and courage died, and I neglected my house and children.

My friends were afraid I might go mad, and they convinced me to go back to New York. I arrived at ten o’clock of a rainy November night and stood in the street with my children, broken and tired, with no place to go, my tears mingling with the rain.

Imagine how I felt then—I set out with the children to seek my husband’s sister. I cannot describe the scene when I came to her that night and told her of the death of her only brother. I had decided that if she would not take me in, I would throw myself into the river.

But I found comfort with his poor sister. She kept me and the children four weeks, and during this time, I placed four of the children in an orphanage. I am now left with three, but I cannot earn a living. If I were to go back to Colorado with the three children, I could make a living peddling, and could possibly plan a future for the four when they got out of the orphanage. There they would have the fresh air, here I am afraid they might inherit their father’s sickness. But it is hard for me to leave the four. I am brokenhearted every time I go to see them. I live here in dreary infested rooms, I can’t earn a living, and my heart draws me there, where my husband died. Of what use is the great city with its people when for me it is narrow and dark?

With tear-filled eyes I beg you, dear Editor, to advise me what to do. Maybe through you I will find solace for my broken heart.

ANSWER:

We believe the writer’s duty demands that she go to Colorado to work there with the hope that in a short time she will be able to have her four children from the orphanage with her. Her devotion to her children will help her overcome her troubles and give her consolation.

Two years later Hine photographed Yetta and the two daughters. But in his caption, he made no mention of the circumstances surrounding the death of Yetta’s husband, or the placement of four of her children in the Orphan Asylum. Perhaps he did not already know that fact when he arrived, and Yetta made no mention of it. Or Hine himself chose not to mention it. We don’t know.

**************************

Let’s go back and review and update my original story in 2014, in light of the new information I have collected since I was contacted by Eve and David.

Samuel and Yetta had seven children: Morris, Bessie, Anna, Irving, Ruth, Sylvia and Henry. Early census records and the admission/discharge records from the orphan asylum listed Morris as Moses, Irving as Isadore, Ruth as Rose, and Sylvia as Sophie. But later, the four children become known as Morris, Irving, Ruth and Sylvia, and that is how the descendants I talked to remembered them.

In 1902, Samuel became ill with tuberculosis and was advised to move to Denver, Colorado. At that time, people with tuberculosis (consumption) believed that the fresh air, year-round sunshine, low humidity and higher elevations provided relief from the symptoms. So Samuel left his family and found a place to live on West Colfax Avenue, not far from the National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives, which opened in 1899.

In November of 1902, three months after Henry was born, Yetta and the children took a train to Denver and joined him. At that time, Samuel was operating a small business, the nature of it unknown. Per 1903 Denver city directory, the family lived at 2757 West Colfax Ave. They stayed together until Samuel passed away on August 22, 1904. He was buried at Rose Hill, a Jewish cemetery in Commerce City, Colorado.

Madelyn Campbell, granddaughter of Yetta’s oldest son Morris, told me a story about the family’s journey to Denver, based on what Morris had told Madelyn’s father Sidney.

“When Yetta and her children went out to Colorado to join her husband, she was very poor. She bought the cheapest train tickets she could get, and she brought some food. She didn’t know how long it was going to take, and somewhere along the way, she started to run out of food. There was a senator from Colorado on the train. I don’t know if he was a state senator or a U.S. Senator, but he was from Colorado. He saw Yetta and the children, and he could see that they were struggling, so he took up a collection on the train and got her a private compartment. And then, at one of the lengthy stops along the way, he took my grandfather Morris off the train, and they went to a store and bought a whole lot of food and brought it back. Yetta didn’t want to accept it because it was not kosher, but the senator told her that God didn’t want her little kids to starve. So she thanked him, and she had enough food for the rest of the journey.”

Daniel Finke, son of Yetta’s son Henry, related to me what his father told him about the trip to Denver.

“Yetta and her husband and her seven children moved to Denver in hopes of successfully treating his tuberculosis. They lived on West Colfax Avenue which, at the time, had a thriving Jewish community. She eked out a living selling sewing notions in Denver and surrounding communities. Samuel was enrolled at the Jewish Consumptive Relief Society. (The Jewish Consumptive Relief Society was founded in Denver, Colorado in 1904 as a non-sectarian sanatorium to treat tuberculosis patients in all stages of the disease.) He died on August 22, 1904. I was working near Denver in the early 1980s and obtained his death certificate. I also located his grave.”

Daniel Finke continues:

“Yetta and her seven children returned to New York City in, I believe, November 1904. Somehow she obtained accommodation after being turned down by charity organizations. Four children (Morris, Irving, Anna, Ruth) were placed in the Hebrew orphanage. Bessie, Sylvia and Henry remained with Yetta.”

“Sylvia told me she completed 8th grade only after writing an appeal to the New York City Board of Education begging them to allow her to complete the 8th grade. Apparently her local school officials wanted her to leave so she could help Yetta earn some more money.”

Official records show that in December 1904, Yetta placed Morris, Anna and Ruth in the New York Hebrew Orphan Asylum. She applied to place Bessie also, but did not follow through. In November 1908, she placed Irving. Morris stayed for five years, Anna for six, Irving for four, and Ruth for ten. All returned home upon discharge.

In 1920, at the same address, Yetta was unemployed, Morris was a plater for a jeweler, Bessie was a sales clerk in a cigar store, Irving was a cloth cutter, and so was Henry. Ruth was not listed. Anna, now married to Isaac Ades, a silk underwear salesman, lived at 49 Delancey Street, about four miles from her mother.

In 1930, the family was living at 819 W. 180th Street, near the site of the George Washington Bridge, which was being built at the time. Yetta was unemployed. Bessie was a sales clerk, and so were Ruth and Sylvia, and Henry was a printer. Up to this point, none of the children listed as living with Yetta were married. But I couldn’t find Yetta’s other children in the census, except for Anna, living in Brooklyn, still married to Isaac Ades, now with three children.

In the 1940 census, Yetta, unemployed, was still living at 819 W. 180th, with Bessie (sales clerk), Ruth (designer) and Sylvia (hotel worker). Living in an apartment right next to Yetta was son Henry, still a printer. He lived with his wife Ruth, and two children, Daniel (5) and Alan (1). Henry was listed as a high school graduate.

According to Henry Finke, in a letter he wrote about the family, Yetta passed away in May of 1955, at the age of 90.

Henry’s son Daniel added the following in an email to me:

“Bessie, Sylvia and Ruth remained with Yetta until her death. They never married, but remained roommates until, one by one, they passed on. Morris was a diamond cutter, and was married with one child. Irving was a furniture salesman, and was married with one child. Ruth was a colorist for engraving and etchings. Bessie was a bookkeeper. Sylvia was a seamstress and a shop steward (or stewardess) with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. Anna was married and had four children. My father Henry was a linotype operator, and was married with two children, Alan and me. He died on May 6, 1988. He was 86.”

Madelyn Campbell, Morris’s granddaughter, told me how Morris became a diamond cutter:

“When my grandfather Morris turned 18, Yetta saw an advertisement in the Jewish Daily Forward saying that the jewelry stores on 47th Street were hiring diamond cutters. She told him that he needed a trade, and he should apply. So he went down, and they trained him and gave him a job.”

“That’s what he did for his entire career. I remember visiting him on 47th Street and watching him cut diamonds. I remember the smell of the olive oil he used. I have a bunch of his tools.”

Anna died in February 1985, at the age 85. Sylvia died in March of 1987, at the age of 86. Bessie died on January 18, 1989, at the age of 95.

Edited interview with siblings Eve Bernstein and David Belkin (grandchildren of Anna Finkelstein. Anna was a sister of Bessie and Sylvia Finkelstein). Interview conducted by Joe Manning on August 28, 2016, and December 2, 2016.

Joe: What years were you born?

David: I was born in 1964, and Eve was born in 1961.

Joe: Was Anna your maternal or paternal grandmother?

Eve: Maternal. Anna was our mother’s mother.

Joe: When did your grandmother Anna pass away?

David: She died in New York City on Valentine’s Day of 1985.

Joe: What was her last name when she died?

David: Ades. She was married to Isaac Ades. The story was that he owned a linen store on the Lower East Side, and that’s where they met. He was a Syrian Jew. He came from Aleppo in the early 1900s. He was about 17 then. They married in New York City and lived their whole married lives there, in Brooklyn, and in Manhattan. Isaac worked for his family’s business, which made pajamas. He was a salesman for the company and traveled quite a bit. The company had a knitting mill in New Bedford (Massachusetts). He was about 95 when he died.

Eve: The Jewish-Syrian community that my grandfather came from was a large neighborhood in Brooklyn. My mother and her parents were very connected to that neighborhood. Anna had a real sense of family.

Joe: How many children did your grandmother Anna have?

Eve: Two girls and two boys. All of them are deceased.

Joe: Did Anna have a career, or was she a homemaker?

Eve: A housewife.

David: She spent about six years in the orphan asylum.

Eve: Our mother used to say that Anna had a hard time at the orphanage, because she was shy and introverted. Our mother used to talk about it. She said Yetta and the other children would go to the asylum and visit the children. They would bring food for them, and they would hide it by sewing it in the hem of their clothing.

Joe: Were she and the other children resentful toward Yetta for sending them there?

Eve: No. All their lives, they adored her. Whenever they talked about her, they would say her name with such longing. I remember my Aunt Bessie in particular. Whenever someone would mention her mother, her response would be, ‘Oh, Mama,’ with longing and love.

David: It’s not like they spent much time talking about what their childhood was like. They never talked about going to the orphan asylum or whether their mother made the wrong decision.

Eve: They certainly forgave her.

Joe: Were you close to Anna?

David: Yes. We had a nice relationship.

Eve: Almost every Sunday, when we were kids, we would go to her apartment to visit.

Joe: Did she dote over you?

Eve: Yes. She was very loving. And she had beautiful taste. Her apartment was decorated beautifully. She dressed beautifully. She was a great cook, and she was smart. She used to do the New York Times Magazine crossword puzzle in pen. That was impressive.

David: She lived a very comfortable life, financially.

Eve: She was truly a ‘rags-to-riches’ story.

Joe: What can you tell me about Morris, Irving, Ruth and Henry?

Eve: We don’t know much about Morris, Ruth, and Irving, but knew Henry. He lived in Washington Heights. He used to come to our grandparents’ home on Sundays, with his wife and children. He wrote a story about the family. We have a copy of it. (See Henry’s story below.)

Joe: Tell me about Bessie and Sylvia.

Eve: Neither of them married. They lived with Yetta in Washington Heights on 180th Street. After Yetta passed away, Bessie and Sylvia moved to the Upper East Side.

David: We used to go visit them in that apartment when we were kids.

Eve: We used to all go on Sundays to our grandparents’ house. We would pick up Bessie and Sylvia and then bring them back home. My grandparents kind of took care of them. Anna’s husband Isaac helped take care of them financially.

Joe: What were they like?

Eve: I don’t remember much about Sylvia, because I wasn’t very close to her. But I was very close to Bessie. She was a pip, a firecracker. She had a spark in her. I loved her. She was always upbeat. They went through lot of turmoil when they were children, but after it was over, they went back to being a family and went on with their lives.

“Aunt Bessie was the outgoing and storytelling type and Aunt Sylvia was more serious. They liked going on guided bus tours around the country and also did some cruises to the Bahamas. I used to go to their apartment most Fridays for dinner after high school. When their 5th floor walkup was demolished sometime in the 1970s for access work for the George Washington Bridge, they moved to a high rise in Midtown Manhattan, subsidized by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union.” -Alan Finke, son of Henry

**************************

The following is a photocopy of a loving story about the early struggles of the Finkelstein family. It was written by Yetta’s son Henry in 1964. The letter, written and printed with a linotype machine, was sent to the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, in exchange for a copy of a Lewis Hine photograph of the family making garters in their apartment. Henry had seen the photo in a presentation at the New York World’s Fair. More about the photo later in this story.

**************************

Lewis Hine caption: Jewish family working on garters in kitchen for tenement home. Location: New York, New York. November 1912.

Is this family, unidentified by Lewis Hine, the Finkelstein family in the first photo taken in 1908? Daniel Finke, Henry’s son, thinks so.

“We have been aware of the Lewis Hine photographs since 1964. Bessie and Sylvia, at the 1964 World’s Fair in Queens, New York, were watching a program when, to their surprise and amazement, one of the Hine photographs appeared on the screen. They told my father Henry, who then viewed the program and contacted the Eastman folks in Rochester (George Eastman Museum, which owns a large number of Lewis Hine’s photographs). In exchange for them providing a copy or two of the photo, plus another photo they said they had which showed Bessie and Sylvia standing, not sitting, father composed a letter on his linotype machine giving details about the family. An additional photograph is on page 187 of Portal to America: The Lower East Side 1870-1925 by Allon Schoener. The same or similar photograph is exhibited at Ellis Island.”

Apparently, Henry obtained copies of the photos he requested, but Daniel does not know where they are. I found Portal to America in my local library, turned to page 187, and saw the photo and caption. Then I searched the Library of Congress collection of Hine’s child labor photos and found it (see photo above). My first reaction was that the mother looked quite a bit like Yetta, but I was not sure whether any of the girls looked like Bessie or Sylvia.

I wondered about the date. If they are the same family, it means that Hine returned to photograph them four years later. I know of only one instance where Hine did this. He photographed a little girl who was shucking oysters, and then three years later, he photographed her again and noted in his caption that she was going to school and no longer working. So if he really did photograph the Finkelstein family again, why wouldn’t he have mentioned it in his caption? And why didn’t he even identify them?

Another problem was that the room they were photographed in looks substantially different from the room shown in the 1908 photo. But that made sense, because according to the census, the family was living at 55 Rutgers Street in 1910. They later moved back to 127 Monroe Street, as the 1915 census shows. So they could have been living at 55 Rutgers Street when the 1912 photo was taken.

I replied to Daniel and explained my uncertainty.

He replied:

“I appreciate your desire for correct attribution of the 1912 photograph. I have looked carefully, using a magnifier. The resemblance of the woman in the 1912 photograph to Yetta in the 1908 photograph is way beyond coincidence, striking and definitive. Cousin Sidney Kelstein and I were in immediate agreement when we viewed the 1912 photograph at Ellis Island.”

I agreed, noting that the resemblance is striking, especially the distinctive eyebrows. Notice in each picture how they extend around to the side of the head.

Daniel continues:

“Verification derives from the brass mortar and pestle on the shelf in the upper right corner of the 1912 photograph. I have seen this mortar and pestle at my cousin’s home many times. He, Sidney Kelstein, Morris’s son, obtained it after Yetta died in early May 1955.”

“Identification of the four children unhappily falls into the category of “probably.” Bessie is likely the young woman in the white blouse. Sylvia is likely the young woman with her head turned to her left. The young girl is likely Ruth, and the boy is likely Morris, as both Irving and my father Henry had prominently hooked noses.”

I replied:

“You have done an admirable job of comparing the photos. As far as identifying the boy. Morris was born in 1894, according to his 1942 draft registration card, and the 1940 census. That would mean that he would have been 18 years old in the 1912 photo. I don’t think he looks even close to 18. The boy could not be Irving either because he would have been 17 in 1912. The boy’s nose does not look hooked, but Henry’s nose might not have been as noticeably hooked at the age of 10, which was his age in 1912. And the boy looks about 10.”

“If this is the same family, Bessie and Sylvia might be the girls on the right. The other girl would not have been Ruth, because she wasn’t discharged from the orphan asylum until August 9, 1914. So the other girl had to be Anna.”

Daniel accepted my explanation that the girl on the left was Anna and the boy was his father Henry.

Based on Daniel’s explanation, Yetta’s son Henry recognized his mother and sisters in the second photo when he saw it in 1964, and of course, Henry would have recognized himself. And Bessie and Sylvia apparently recognized themselves. Daniel was about 20 when Yetta died, so he would have known her well. So their observations have great credibility.

At that point, I felt that the preponderance of evidence, especially the recognition of the mortar and pestle, a family heirloom, appeared to confirm that the Finkelstein family was in both photographs. But I wasn’t sure that the evidence was definitive.

But then Madelyn Campbell solved that problem.

“My father Sidney was a history teacher and photographer. One day back in the 1970s, he was looking through a book of Lewis Hine photographs, and he saw a picture of his grandmother Yetta. He recognized her pocket book hanging on the wall. That was the photograph that was taken in 1912 that you posted in your story. It is in the museum at Ellis Island.”

Madelyn told me she has the mortar and pestle in the 1912 photograph, and then sent me a picture of it. It was a match.

Madelyn told me that her father thought that the child in the photograph sitting to Henry’s left was not Sylvia, but a neighbor instead, either a boy or a girl, who was visiting. He explained that all the children were “dressed up” (perhaps for the photograph), except the neighbor, and that the child was not working on garters. We may never know for sure.

Yetta Finkelstein with (clockwise): Henry, either Sylvia or neighbor, either Bessie or Ruth, and either Bessie or Ruth, November 1912.

*Story published in 2017.