Lewis Hine caption: Antonio Martina, 53 Carolina Street, Buffalo, N.Y. 11 years old last summer. Attends School #1. He and a 13-year-old sister worked in sheds of Ellis-Canning Factory, Brant, N.Y., snipping beans at 1 cents a pound. Left for the country in May, returned late in September, losing about 7 weeks of school. He sells papers reluctantly. Location: Buffalo, New York, March 1910.

“Every time I saw him, he gave me a quarter. As I got older, and I was working and making $5.00 an hour as a lifeguard, I told him I didn’t need a quarter anymore. He almost started to cry once when I told him that, but it meant a lot to him for me to take it, so I did as a favor to him.” -Bill Reynolds, grandson of Anthony Martina

Lewis Hine took 55 photographs in Buffalo in February and March of 1910. Among them were 19 of newsboys, and 29 of children who worked at farm-based canneries in the outlying towns. According to Hine’s caption, it looks like Anthony did both jobs.

According to Houses of Worship: A Guide to the Religious Architecture of Buffalo, New York, by James Napora, the Lower West Side of Buffalo (where the Martina family settled) was largely populated by Sicilian immigrants who came to the US in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Most were farm families who left because of poor crop production and high taxes.

But conditions in Buffalo were not much of an improvement. They were forced to live in overcrowded and substandard housing, and good jobs were not readily available. Having only farming experience, many took seasonal jobs picking and processing fruits and vegetables on farms south of the city. Some worked at the docks on Lake Erie, and on road and building construction.

By the 1920s, they had formed numerous benevolent societies and charitable organizations, some affiliated with St. Anthony of Padua Roman Catholic Church, which they established in 1891. They also established the first Italian language school in the US.

The following are excerpts from a 1907 report conducted by Pauline Dorothea Goldmark, for the New York Child Labor Committee:

At one school (Buffalo Public School No. 2) the school records show that seventy-seven children were absent from school at the beginning of the fall term (September, 1907) on account of being employed at the canneries. These children ranged from eight to fourteen years in age and stayed away for periods varying from three to twenty weeks. The local boards in the towns where the canneries are situated failed lamentably to secure the attendance of these children. Only seven of the whole number attended local schools, most of them going for only one or two weeks, when forced by the truant officer. As the school term for the whole year lasts for only thirty-six weeks it will be seen that these children are in large part deprived of the benefits of an American education. An effort to learn why local school authorities in the cannery towns are so lax in their enforcement of the school laws brought forth this statement from a principal of a school near a cannery:

“I have a total registration of forty-five Italian children. Of this number about thirty-five are permanent residents here. Most of them are exceedingly irregular in attendance until after the cannery is closed. Not only can they obtain work without question at the cannery after school has commenced in the fall, but I am convinced that the superintendent encourages the children to work in the canneries. My predecessor here tells me that last year the local truant officer went to the cannery in an effort to locate a number of Italian truants and was ordered off the premises by the factory superintendent. This, of course, is illegal, but the cannery seems to be above the law in several respects; this year we have made repeated attempts to search the factory for truant children and have not infrequently discovered them hiding with the knowledge of the factory superintendent. All these children were truants only because of the opportunity to work in the cannery. When the cannery closes we never have any trouble in compelling the attendance of our Italian pupils. They are fairly diligent and regular in attendance, but will leave school at the first opportunity to secure paying work, and even if they were not willing, their parents would make them.”

The canner’s position in the community is such that he is able to defy local authority. His attitude alone decides whether the children shall work in the factory or attend school. The parents are allowed to follow the dictates of their cupidity and are encouraged to recognize no authority except that of their employer. The inevitable result is to keep the children out of school and at work. The foreigners are at the plant to make money. Doubtless they are unconscious of the harm they are doing to their own children. But the canners know, or should know, that these children are being exploited in their service. Moral responsibility does, and legal responsibility as well should rest with them. Ignorant and untaught, deprived of all the immunities of childhood and of the benefits of consecutive school life, the children in the canneries show little promise of developing into citizens more valuable to the state than their immigrant parents. The employment of children in cannery sheds has in the past been countenanced on the plea that the work is easy and resembles agriculture more than factory labor.

The following reports of persons who were employed in these canneries during the bean season give some idea of the number of young children actually seen at work, and the shockingly long hours they are employed:

I started to work at 7 a. m. and was put on piece work in the shed. Sixty women and thirty children were here all stringing beans. They were sitting on boxes; forty-five of the sixty were Italians and they had all their children with them. One woman, a Mrs. T., had two girls seven and nine years old, with her. She began work at 5 a. m. and worked till 9:30 p. m. The two little girls worked the same length of time. They complained of being tired when their mother had gone for beans, and said their limbs ached. They did not leave for meals but ate bread, etc., in the shed.

At 5 o’clock I counted the children in the shed – there were actually eighty under fourteen years, and a large proportion of these were not more than eleven years. There were four nursing babies close to where I had been sitting. In the evening I went over for an hour more and at 9 o’clock counted fifty children under fourteen. Italian children from eight years up do regular snipping, but some of the more spirited boys will play part of the time.

Josephine S., aged ten years, worked all day from 7 a. m. till 5 p. m. and snipped thirty pounds of beans. Henry, her brother, is nine years old, and he said he was going to collect $2.60 for the week. They worked all day, stopping only long enough to eat lunch without leaving the work place. Both children are dirty and thin.

Edward H., fourteen years. For at least a week he has been beginning work at 7 a. m. and working till between 9 and 10 p. m., helping at the sorting tables. Told how he worked last year from 7 a. m. till 9 and 10 at night, sometimes till 1 or 2 the next morning, keeping this up for days in succession; and one Saturday he worked from 6 a. m. till 5 a. m. Sunday with less than two hours off for meals. He was thirteen years old last year when he worked, and other boys the same age worked the same hours. He has begun at 7 and worked till between 9 and 10 at night since I have been here.

Lewis Hine caption: Children from school No. 2 in the Italian district Terrace[?] nr. Genesee St. Many of these children spend their summer vacations in the canning and fruit picking settlements where their parents go to work during the season. Feb. 8, 1910, Buffalo, N.Y.

According to the 1900 census, Antonio (Anthony) Martina, lived with his parents, Orazio (later called Frank), a day laborer, and Francesca (Fedele) Martina, and five siblings, including sister Salvatrice, who was the 13-year-old sister Hine referred to in his caption. They rented an apartment at 25 Trenton Street, in the Italian Lower West Side. Frank and Francesca married in Sicily about 1882, and came to the US in about 1891.

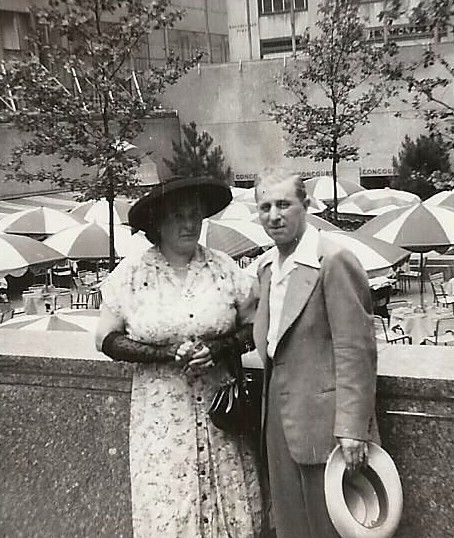

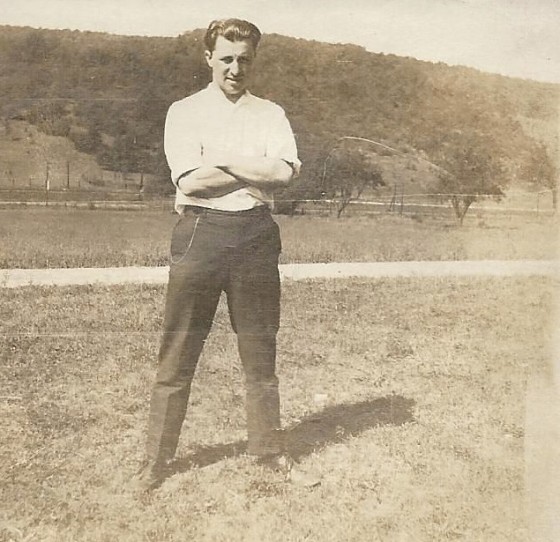

By 1910, the family had moved a half-mile south to a rent at 53 Carolina Street, where Anthony was photographed. Both addresses are now situated within modest cluster housing developments. By 1920, the Martinas had bought their first house, at 228 West Avenue, also in the Lower West Side. The multi-family house, build in 1900, still stands. Anthony, who had left school after the ninth grade, was already a clerk for the Iroquois Gas Company, where he would ultimately work for 45 years. His father Frank died about 1926, and mother Francesca died about 1933.

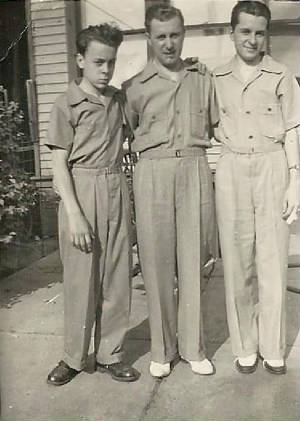

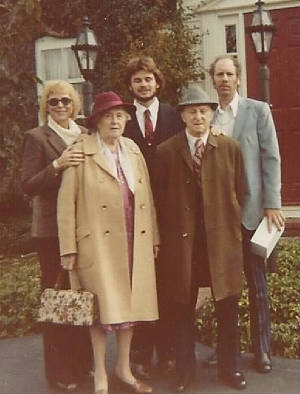

Born in Buffalo on July 2, 1897, Anthony A. Martina married Sylvia Davis in the early 1920s. They had three children, two boys and a girl. Anthony passed away in Buffalo in January of 1986, at the age of 88. Sylvia died three years later.

None of their children are living, but I located Bill Reynolds, a grandson, who lives near Buffalo.

Edited interview with Bill Reynolds (BR), grandson of Anthony Martina. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on August 26, 2012.

JM: What did you think about the photograph of your grandfather?

BR: I was very interested. I had never seen any pictures of him when he was young, but I can definitely tell that it was him.

JM: Did you have any idea that he had been doing this as a child?

BR: No. I was born in 1960. He was 63 then. I never learned much about his younger years. I know that he worked for Iroquois Gas Company for 45 years. He told me that in World War I, he almost went to the war, but he got pulled back right at the end. He was about to leave. He kissed his mother goodbye, and then she came running out as he was pulling away and said to him, ‘The war is over, come back.’ They had just announced it on the radio. My grandmother also told me that story.

My mother left my first father when I was one year old. At that point, we moved in with my grandparents, at 349 Auburn Street, across the street from where my mother and I were living at 357 Auburn. My grandfather bought the house so that we could all live together. Up till then, they only had a small apartment. I lived there until I was eight, and then my mother remarried. We moved further over on the West Side, and my grandparents stayed on Auburn. Later, they moved into an apartment building on Lafayette. My grandfather died in 1986, at the age of 88.

JM: What was your mother’s name?

BR: Sylvia June Martina, my grandfather’s only daughter. She always went by S. June. She didn’t like Sylvia, because that was her mother’s name also. My grandmother’s maiden name was Sylvia Davis. She was from Hornell, New York. She wasn’t Catholic, but my grandfather was.

JM: What did your grandfather do at the gas company?

BR: He worked in the office. He did a little customer service, but he mostly did paper work. I was young when he retired, maybe five or six, I’m not sure. Iroquois is now called National Fuel Gas Company.

JM: In the 1920 census, your grandfather’s brother Charles was listed as a lawyer.

BR: I remember him being a businessman. He owned half of the Goldfield Wine Company. His sister’s husband owned the other half. He was a millionaire. They also owned a Pontiac dealership.

JM: What was your grandfather like?

BR: We had kind of a father and son relationship, because I didn’t have a father until I was eight. We did a lot of things together. We’d play basketball in the yard, and he would teach me how to shoot. We went to picnics a lot. At the church, they called them lawn fetes, and they had seven or eight of them a year. And we would go to the annual Iroquois Gas picnic. They had games and things for the kids.

JM: When your mother remarried and you had a father, did your relationship with your grandfather change?

BR: No. We still stayed close. I would walk to my grandparents’ house often, even run when I got older and got athletic. My grandmother always had a bowl of M&M’s out for me. My grandfather and I would watch baseball games a lot. He had met Johnny Bench, the (Hall of Fame) Cincinnati Reds catcher, who had played for the (minor league) Buffalo Bisons back in the late 1960s. Johnny had given him a ticket to a game once. So we always watched the Cincinnati Reds games. He would say, ‘You gotta watch Johnny Bench.’ That’s how I got to like baseball.

JM: Did you go to Bisons games with him?

BR: By the time I got old enough to do that, the Bisons had folded. But in the 1980s, they came back around again.

JM: Was your grandfather in good health up until he died?

BR: Yes, he was. But at some point, he slowly started losing his sight, and he didn’t tell anybody. He waited too long. He had glaucoma, and if he had been treated sooner, they might have at least slowed down the process. When he finally couldn’t see much at all, he seemed to lose his will to live. It was hard for my grandmother to take care of him, so they went into a senior home. But they couldn’t be together, because he needed lots of care, and she didn’t. He didn’t even last six months.

My grandfather told me that he didn’t get his first car until he was 35 years old. He told me a story about him and my grandmother coming home from Hornell once. There’s a town called Warsaw on the route. It has a big hill. It was icy, and he couldn’t get up the hill, so he managed to get up by backing up all the way. I can’t imagine doing that.

I remember that when he decided to retire, he told me he did it so that he could be home more often with me. He was a very gentle man. He was always trying to help people. Every time I saw him, he gave me a quarter. As I got older, and I was working and making $5.00 an hour as a lifeguard, I told him I didn’t need a quarter anymore. He almost started to cry once when I told him that, but it meant a lot to him for me to take it, so I did as a favor to him.

He loved to paint pictures. He painted a picture of Santa Claus once. I still have some of those pictures. He used to tell me, ‘I’m not very good at it, but I like doing it.’

JM: Do you think you are like your grandfather in any way?

BR: I’m sure that I am. After all, he practically raised me. I wish I could be more like him. He was gentler than me. Sometimes I am a little rough around the edges.

JM: Have you lived in the Buffalo area all your life?

BR: When I was in my twenties, I moved away for a while and traveled around a lot. I lived in Pittsburgh and Colorado and San Diego. But I came back because I liked the area, and my family was all here.

JM: So if you go back to your grandfather’s parents coming to Buffalo in the late 1800s, your family on the Martina side has lived in the Buffalo area for about six generations.

BR: That’s right, for the most part.

JM: Do you think about your grandfather any differently, now that you have seen the photo?

BR: Maybe that was not an enjoyable time for him, and maybe that’s why he never talked about it. But he raised a family, lived a long life, and influenced a lot of people.

Anthony Martina: 1897 – 1986.

*Story published in 2012.