Lewis Hine caption: Elbert Hollingsworth, ten year old cotton picker. Picks 125 pounds a day. Also Ruby Hollingsworth, seven year old cotton picker. Works all day, early and late, in the hot sun. Picks about thirty-five pounds a day. Father, mother, and several brothers and sisters pick. They get only five or six months of schooling. “It’s not ’nuff,” the father said. The children said “We’d rather go to school.” Address Box 18, R.F.D. Location: Denison, Texas. September 1913.

Lewis Hine caption: Ruby Hollingsworth, seven year old cotton picker. Works all day, early and late, in the hot sun. Picks about thirty-five pounds a day. Father, mother and several brothers and sisters pick. They get only five or six months of schooling. “It’s not ’nuff,” the father said. The children said “We’d ruther go to school.” Address Box 18, R.F.D. Location: Denison, Texas, September 1913.

“I can’t imagine them out there in that hot sun all day long. These days around here, you don’t go anywhere without a bucket load of water. That’s not something I would ever do to my children. We know now that much of what we buy is being manufactured by children in China, but we’re complacent about it. It’s not affecting us because we don’t have to look at it. If we went over there and saw it, I think we would want to change it.” -Victor Hollingsworth, son of Elbert Hollingsworth

The following is from The Survey, published February 7, 1914:

“Come out with me at sunup,” says Mr. (Lewis) Hine, “and watch the children trooping into the fields, some of them kiddies four or five years old, to begin the pick, pick, pick, drop into the bag, step forward; pick, pick, drop into the bag, step forward, six days in the week five months in the year, under a relentless sun. The mere sight of their monotonous repetition will tire you out long before they stop. Their working day follows the sun, and not until sundown will they leave the fields. Ruby, aged seven, stopped working long enough to say, as I stood by her, ‘I works from sunup to sundown, an’ picks 35 pounds a day.’ Imagine the number of feathery bolls that must go into the bag hanging about her neck to tip the scale at 35 pounds!”

“The result of a few years of this incessant grind, long hours, physical strain, lack of proper food and care, and lack of mental stimulus? What can it be but physical degeneration and moral atrophy? We have long assailed (and justly) the cotton industry as the Herod of the mills. The sunshine in the cotton fields has blinded our eyes to the fact that the cotton picker suffers quite as much as the mill hand from the monotony, overwork, and hopelessness of his life. It is high time for us to face the truth and add to our indictment of King Cotton a new charge – the Herod of the fields.”

“One of the most pitiful things about the situation is the indifferent acceptance of conditions by people generally. I heard very little anxious comment except from school teachers. Ruby’s father, who said, ‘They git five months’ schoolin’ and it ain’t ’nuff’, stood out among all the parents I interviewed as a rare exception. It is quite possible that the Texas farmers are not so indifferent to the exploitation of their children as appears, for they are literally ‘up against it.’ They are transient renters, weighed down by debt, illiterate, and dependent upon the crops.”

“But I place first and foremost in any program of change the restriction of child labor. Children must be left free to go to school. At a recent conference of the Texas State Board of Charities and Corrections, all were agreed that compulsory education is the greatest need of Texas today. Patriotism demands that we save the children. We must begin at once to lay the foundation for the farmer of tomorrow by a longer period of child hood today, with better preparation for work and better training for life.” -National Child Labor Committee

**************************

According to the census, William and Rachel (Keesee) Hollingsworth were renting a farm in 1900, on land located in the Choctaw Nation, later to become the state of Oklahoma. Their farm was situated in what is now the unincorporated village of Blue, Oklahoma, about 30 miles northeast of Denison, Texas, where Lewis Hine photographed Elbert and Ruby 13 years later. Mr. and Mrs. Hollingsworth had married in about 1895, and in 1900 had two children, Herman and Myrtle. It was William’s second marriage. Elbert Payton Hollingsworth was born in Blue on August 17, 1903; and Ruby Edith Hollingsworth was born in Denison on January 21, 1906.

According to the 1910 census, the family owned a farm in Denison, where they apparently grew cotton. I could not find them in the 1920 census. In 1930, William was still living in Denison and was working as a janitor for a railroad office. His wife Rachel and daughter Ruby were still in the home. William died in 1932, and Rachel died in 1943.

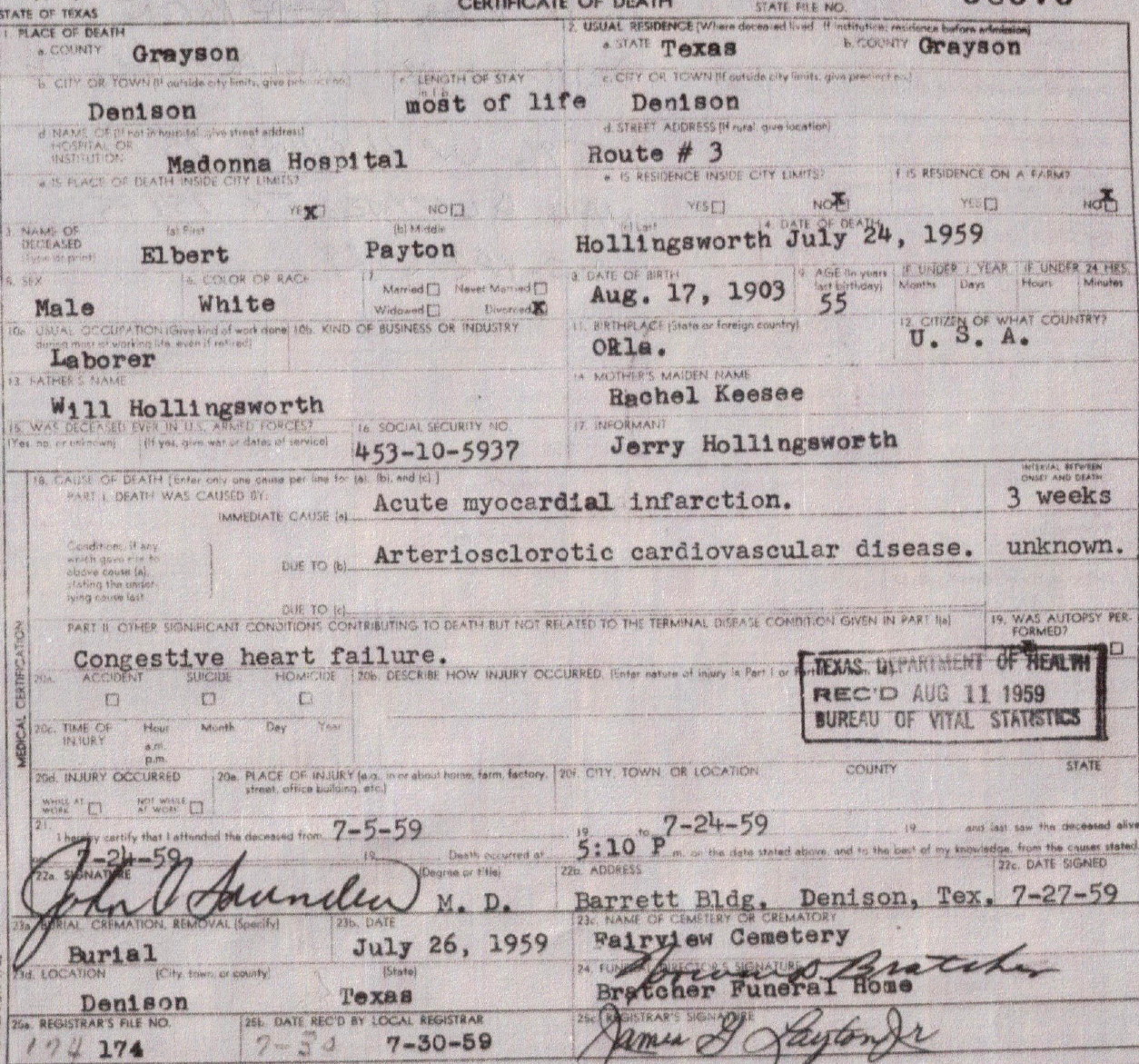

Elbert married three times. He married Kathleen Irland in Texas in 1923. He married Julie Cathey in Oklahoma in 1929. In the 1930 census, they were boarding with a family in McLennan, Texas. They had no children at that time. Elbert was a fence builder, and Julie was listed as a photographer. He married Julia May Reynolds in 1934, also in Oklahoma. They had five children. Another two died in infancy: Elbert Jr. in 1935, and Delores in 1939. Elbert died in Denison on July 24, 1959, at the age of 55.

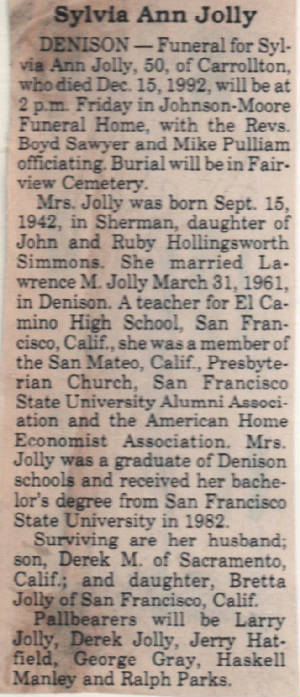

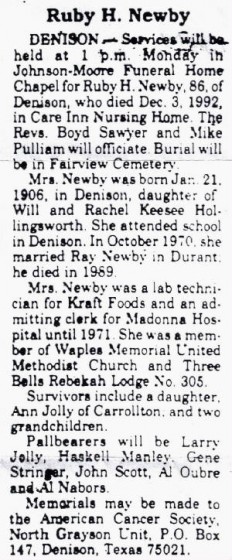

Ruby married John Simmons in Durant, Oklahoma, on July 27, 1934. They had one child, Sylvia Ann, born in 1942, and they eventually divorced. Ruby married Raymond Newby in 1970. He died in 1989. Ruby died in Denison on December 3, 1992, at the age of 86. Daughter Sylvia married Lawrence Jolly. She died in Dallas at the age of 50, only eight months after her mother died. She had a son, Derek, whom I could not locate; and a daughter, Bretta, who died in 2008.

After finding an obituary for Elbert’s third wife Julia (died in 2010), I contacted one of their daughters, Rachel Glenn, who connected me to two of her brothers, Victor and Jerry. None of them had seen the Hine photographs.

Edited interview with Rachel Glenn (RG), daughter of Elbert Hollingsworth. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on November May 18, 2011.

JM: What did you think of the pictures?

RG: I was very excited. I didn’t know anything about him working on a farm and picking cotton.

JM: When were you born?

RG: 1943. My mother and dad divorced when I was about nine years old. I never knew his side of the family. I hardly know anything about his sister Ruby.

JM: Did you continue to have a relationship with your father?

RG: Absolutely. He still lived nearby in Denison.

JM: When you were born, where were your parents living?

RG: In Denison.

JM: Did they own their home?

RG: Yes.

JM: What did your father do for a living?

RG: He worked at a Dr. Pepper plant. I remember going down to see him at the plant, and he was on the line putting on the bottle caps. Prior to being at Dr. Pepper, he worked for the railroad and he was a truck driver. My mother told me that he was a bouncer at one time, while she was a hat check girl at the same place. My dad only got as far as the sixth grade.

JM: When your parents divorced, did your mother continue to live in the home they owned?

RG: Yes. My mother still owned it when she died. We didn’t have a whole lot of money. We had a nice little house. It’s still there, but me and my brothers are trying to sell it.

JM: How many children did your father have?

RG: He was married three times. His first marriage was to a schoolteacher who already had a little girl. Then he married again, and I think he had two children. One of them was named James Allen Hollingsworth. That’s what I was told. Then he married my mother, Julia May Reynolds. They had five children: Gerald, Charles Victor, Rachel Louise, Donna Kay, and Jennie Lee. That was his last marriage.

JM: How did your mother support the family after the divorce?

RG: She worked, sometimes at three jobs. She worked at Madonna Hospital and another hospital, and for a convenience store at night at one time. I don’t know how she did it, but she took care of us. She retired from Texas Instruments.

JM: What was your father like?

RG: We had a great relationship. He loved children. He was like a child in a lot of ways. He loved taking us out in the country and walking in the woods. He was a poet in a way. When we were walking around in the woods, he’d say things like, ‘Let the grass tickle your feet and feel the wind blowing on your cheeks,’ and stuff like that. He taught us how to shoot a .22 rifle. He’d take us fishing, and he loved to tell stories. He also loved to hunt. He said that when he was a boy, he lived way out in the country. He said that he went camping one night when he was about 13 years old. He went way out in the woods, and he heard a big scream, like a woman, but it was a mountain lion. He said that he ran all the way home, but this mountain lion was trailing him. He barely got in the front door. That was about the only thing he told me about his childhood.

He had a bad heart. When my dad had his last heart attack, he was at Madonna Hospital. I went in there to see him, and Ruby was the receptionist. I walked up to her desk, and she just stared at me, and then she followed me all the way down to my father’s room. But she never said anything. My mother turned around and gave her a look, and Ruby turned and left. My mother knew who she was, because she also worked at Madonna Hospital.

JM: How far did you get in school?

RG: I got a far as the tenth grade. I got married at a very young age. I had four children. I worked about 18 years as a receptionist and administrative assistant at a bank. When I was a young woman, I worked at a cotton mill. I didn’t stay there very long because I’m a small person and the work was just too hard for me. And I was a nurse’s aide for a long time.

My dad died of a heart attack when I was about 16. When I saw the pictures you sent me, my heart just went out to him. It was sad to see that he and his sister had to go out and work at that age. My father was a lonely man after Mom divorced him. One day, he came over and sat in the front yard for a long time. My mother never said a word; she just let him stay there as long as he liked. We were all at the hospital when he had the heart attack, and I think he knew we children all loved him very much. Toward the end, he was going to church, and he turned out to be a good Christian man. He was a member of Parkside Baptist Church. The picture is a wonderful gift. I loved my father very much, and now I love him even more.

Excerpts from my interview with Victor Hollingsworth, son of Elbert Hollingsworth. Interview conducted on June 14, 2011.

“My dad and I used to go hunting together. He was an excellent shot. He was one of those people that never missed. He was a funny guy. He liked to laugh and have fun and tell stories. He told me once that he did some ranching up in Oklahoma when he was a young man. He was on horseback in a place that was really cold, and he saw some smoke coming up from the ground, so he went over to see what it was. There was an Indian family there that had a house under the ground. They invited him in. The woman gave him a big bowl of soup. He ate all of it, so she gave him another bowl, and he ate all of that, too. She offered him another bowl of it and said, ‘I’ll dig down in the bottom of the pot and get a lot of puppy dog for you.’ The soup was made out of dog meat.”

“We didn’t know it at the time, but he had a sleep disorder. He would fall asleep while he was telling us a story. That may be why he had trouble keeping a job. We had a lot of tough times in those days. We didn’t have any money. I don’t remember Dad having a car while I was young. In those days, he had to walk everywhere we went.”

“My mom and dad divorced when I was about 13. My mom had to work in whatever jobs she could get. She was a very tiny woman. At one time, she worked in a Safeway plant, and she had to pick up big cases of food off the line, and she would come home with big bruises on her arms. She worked at the hospital in the supply department, and she worked for Texas Instruments. She didn’t have much of an education, but she was real smart.”

Excerpts from my interview with Jerry Hollingsworth, son of Elbert Hollingsworth. Interview conducted on June 21, 2011.

“My father did a variety of jobs. He was the type of person that when he was ready to quit, he quit. For the most part, he was good to all us kids. We went hunting together and fishing together. He enjoyed life. He didn’t drink or pop pills, none of that stuff, but he couldn’t leave food alone. If there was one more piece of meat on the table, he had to have it. He weighed about 300 pounds. He was big and stout like a grizzly. And the only place he didn’t have hair was on the bottom of his feet, the palms of his hands, and his forehead.”

“He worked once with two guys who were painters. They would paint two sides of a house while my dad painted the other two sides by himself. He would do it like an artist painting on a canvas, but when he got finished, the other two guys would still be painting. When he didn’t have any money, he would go out and kill a bunch of wild game. For a man that size, he could run awful fast. He could lift almost anything that you would ask two men to lift. He took a 300-pound calf out of the back yard one day, wrapped it in his arms, went down across the yard, and laid it in the back of a pickup truck. He used to work at Oak View Inn as a bouncer. That’s where he met my mother. Before that, he had been married two times.”

“He wouldn’t hold a steady job, so he was always going off to look for work. He’d be in the living room, and you’d go in there to say something to him, and he’d be gone. He’d be on a freight leaving town. Three months later, he’d show up. He’d have a wad full of money; or if he didn’t, he’d get his gun down off the wall and go hunting.”

“I remember that we had chickens in the back yard. When my father wanted chicken for dinner, he’d cut the straw off a broomstick, and then he would take the stick, pick out the chicken that he wanted, and hit that chicken right in the eyes. He seldom missed. Then he’d tell me to go get it and bring it to him, and he’d cut off his head.”

“I was the oldest of five. I had one brother and three sisters. We were poor, but for most part, we were happier than most people are today.”

“He mentioned a couple of times about picking cotton as a kid. He told me, ‘If you think life is rough, just think about a boy like me who had to pick cotton.'”

Elbert Hollingsworth: 1903 – 1959.

Ruby Hollingsworth: 1906 – 1992.

*Story published in 2011.