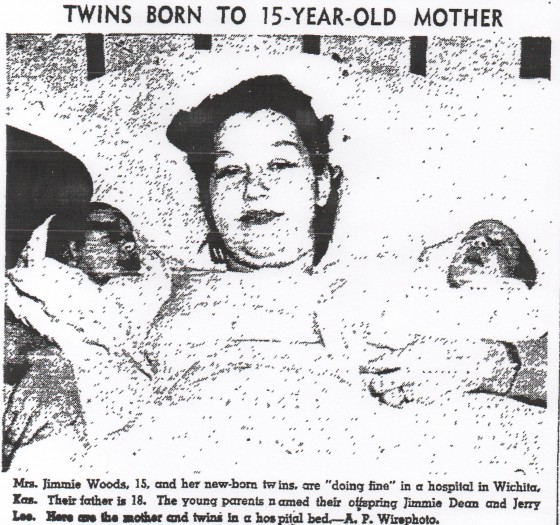

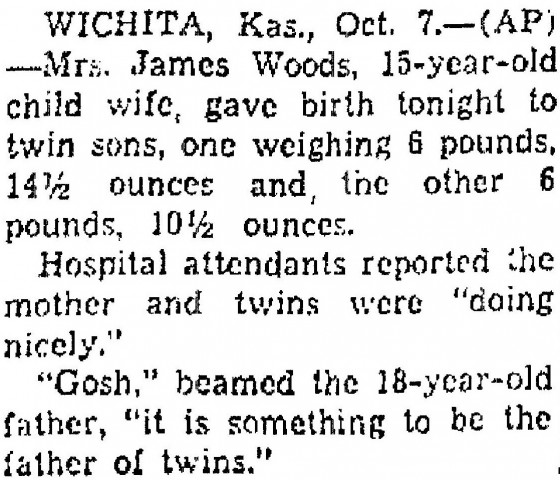

In the fall of 2014, 77 years after this picture was taken, and in a town 1574 miles from Wichita, I stumbled upon a box of old Associated Press photographs in a store that sells industrial artifacts, handmade goods and various curiosities. The photo caught my attention immediately. I bought it for three dollars and said to the clerk, “I want to track down the family. The twins might still be alive, and they might not have this picture.”

The town, Turners Falls, Massachusetts, is located on the Connecticut River; the store is called Loot.

I began my research (on Ancestry.com) by looking up Woods in the 1940 census for Wichita. I found James and Maxine Woods living in a rented house at 1622 West Second Street. They had three children: Jimmie and Jerry (the twins) and nine-month-old Joyce. James worked as a bookkeeper for the police department. Both parents had a ninth-grade education.

Also posted on Ancestry were portions of the Woods family tree, which included a sad piece of news. Maxine died in 1949, at the age of 27, when the twins were only 11.

And in a newspaper archive website, I found the Associated Press photograph in several newspapers, including the Oakland Tribune (CA), and short articles about the birth in a dozen newspapers, including two in Alberta, Canada.

A few days later, I found a phone number for one of the twins, James (Jimmie) Woods, and called him. He was amazed. He told me that he had a faded clipping of an article about the birth, which included the picture, but that he had never owned or seen a print of the photograph. So I sent it to him. A few weeks later, I interviewed him over the phone. To my surprise, he said, “This might be the most exciting thing I’ve ever done on my birthday.” It was his 77th.

The following is my interview with James Woods:

Woods: My dad worked for Boeing in Wichita. Boeing transferred him to California during the war. He wasn’t drafted because he had too many children.

Manning: In the 1940 census, your parents’ address in Wichita was listed as 1622 West 2nd St.

Woods: I remember that the house was very small.

Manning: You knew your mother for about 12 years. What do you remember about her?

Woods: She was dedicated to her kids. She was very kind, and probably spoiled us. I recall that when Jerry and I were in the 2nd grade, we were bullied a lot, and my mother would comfort us when we came home crying. My dad worked many, many hours, so my mother was the peacekeeper, the peacemaker, and the one who consoled us when we had problems. I was only eight years old when she got sick. She was admitted to Los Angeles County Hospital, and stayed there the rest of her life, only occasionally coming home for a few days. The hospital was 25 miles from our house.

Manning: What was her illness?

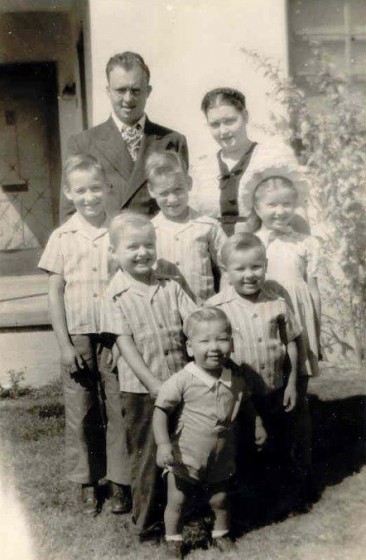

Woods: She had a hole in her heart about the size of a quarter. It was congenital. By the time they found it, in 1946, it was diagnosed as terminal. She had all of her six children by then: Jerry and me, Joyce, Richard, Alfred and Clifton. She died three years later.

Manning: Did you visit her in the hospital frequently?

Woods: No. We kids visited her only one time, and that was when she was given only a short time to live. In those days, kids were not allowed in hospital rooms.

Manning: Who took care of you?

Woods: My dad had to hire housekeepers, because he was always working or visiting my mother. When she first went to the hospital, he was working for a company that installed electronic equipment. During the war, they installed the equipment on warships. When the war ended, the company started installing electronic equipment in yachts and boats at Newport Beach. We moved to Costa Mesa at the end of the war. He was promoted to branch manager. But he visited my mother so much in the hospital that the company finally had to let him go. That really devastated him. But then he started his own electrical construction with a friend. He did work mostly on homes, and they benefited tremendously from the housing boom at that time.

When my mother passed away, my dad married Questa Miller. She was about eight years younger than him. Her family went to a church where the pastor was married to my dad’s sister. When Questa graduated from high school, she enrolled in college in Pasadena, California. That was in 1948.

After my mother died, my dad’s sister introduced Questa to my dad. She was concerned that he needed someone dependable to help him care for the children. Four months later, they got married. My father hadn’t really had wife for three years. Questa was only 21 at the time, and I and my brothers and sister were not that much younger, and yet she raised us beautifully. She and my father did not have any children together. Questa is 88 now. My father died in 2012.

In 1953, Dad and Questa moved us to Alaska. They were weary of the California rat race, if you know what I mean. He happened upon a 240-acre piece of property for sale there, bought it for very little money, and we settled there. He continued his electrical construction business.

When I graduated from high school, we were living in Seward, Alaska. I was a very good student. One of my teachers recommended that I enroll at the Colorado School of Mines. But I declined, and joined the Navy instead, where I learned electronics.

Manning: What was Jerry doing then?

Woods: He went to Fullerton Junior College in California for a year, and then joined the Navy also. I wound up working in electronics most of my life. So did Jerry. My dad still owned his business when Jerry and I got out of the Navy. We worked with him, and eventually bought into my dad’s business. So Jerry and I followed the same path pretty much. We’re both retired now.

Manning: Are you identical twins?

Woods: Yes, and in that photo, I have no idea which baby is me.

**************************

In 2003, James Woods, Maxine’s husband, wrote and self-published a book titled Facing A Lifetime of Challenges, Trials, Tests, and Triumphs. I found it online and purchased a copy. The following is an excerpt. (Reprinted with permission of the Woods family).

Shortly after starting to attend the West Side Nazarene Church, I met a cute little girl named Maxine Knowles. She would invite me home for Sunday dinner and this was neat. Besides, I would eat lunch there. Maxine and I became quite fond of each other. I thought she was older than me, so I would not tell her my age. She was so mature. Later, we did find out each other’s ages, and she was thirteen and I was almost seventeen.

About this time, I had been living with the Frenches for two years (Editor’s note: James was working for electrician Earl French), and was feeling I would never become an electrician and make decent money, so Mr. French raised my salary to ten dollars a week. By that time, I had completed my apprenticeship at the age of 18 and wanted to get my journeyman license and make more money so we could get married and have a home of our own.

In expressing my love for Maxine, I felt that if we married and had a family I would be accepted as the man I was and not the kid in overalls anymore. After discussing this with Maxine, we decided to do something about it. So on New Year’s Eve, 1936, we planned to elope. We knew we would have problems. I was eighteen and she was fourteen. We did not want to lie. I felt that, even though Maxine had a brother who had gotten married at fifteen years of age, her parents would probably not give consent. I came upon a foolproof way not to lie. We went to the Marriage License Department, but before going in, I took two slips of paper, put the number twenty-one on one and the number eighteen on the other. We put them in our shoes, mine was twenty-one, and hers eighteen. We went in, put our money on the counter, and asked for a marriage license.

The clerk asked me about my age. I said, “I am over 21.”

When he looked at Maxine, she said, “I am over 18.” We looked and acted very mature and the license was issued. Maxine had a girlfriend whose uncle was a minister. We made the arrangements with him for a New Year’s Eve marriage.

Maxine’s parents were at a New Year’s Eve church affair for adults and our age group was having a New Year’s party at Maxine’s home. We left the party early, got married, went back to the party, and made the announcement. About that time, the Knowles came home and we told them. Mrs. Knowles, Maxine’s mother, came unglued. To this day, I don’t blame her. Mr. Knowles said, “I will have it annulled.”

I informed him, “I have already rented an apartment and we will leave for the apartment now.”

He said, “You may, but she won’t.”

I was very serious when I said, “You can have it annulled, Dad (that was a mistaken title for that tense moment), but where I came from, men only marry one woman and Maxine is my wife now. If you have it annulled, it won’t do much good as I will just marry her again.”

“Not before she is eighteen, you won’t.”

I declared, “If not before then, then at that time we will marry again, and she agrees with that.” Well, it sure was a long, lonely walk home that night. Saturday, I returned to the Knowles residence. Mrs. Knowles gave me one of those looks. I don’t blame her, she had one great girl and we both knew it. However, she still had three more girls at home and two married, and I had none. Well, Maxine and I did some serious planning. I told her I would see her on Sunday, and left.

Sunday morning we sat together in Sunday school and church, and after church, I went my way and she went home to her folks. It surely looked like they had won out. Maxine said that her dad was taking Monday off to go have the marriage annulled, so our plan needed to go into effect quickly. Sunday evening service came and went. I left immediately when the service was over as Maxine’s dad went out to warm up the car. I walked by, looking very downhearted and dejected, and turned at the next corner. I ran up to Maple Street and right to the next corner where I met Maxine. She had gone out the back stairs of the church and up the other street to Maple where we had friends who drove us to our apartment, which was just two blocks from her parents’ home. Would you believe it? We had groceries and no reason to go out, so we stayed home all week, seeing her dad go by each day and not knowing what would happen next.

Maxine had worn several pairs of undergarments and three dresses, one over the other, so she had enough clothes to last several days and I had all my clothes. Next Sunday, we got dressed and went to Sunday school. We did not go to our former Sunday school class; we went to the young married people’s class. The Knowles did not come to Sunday school but came into the church service.

When church was over, Mr. Knowles came up to me and said, “I want to see you outside alone.” I could almost feel two black eyes. He continued, “What are you going to do now? Mr. French said he has fired you since you did not show up for work this week. You kids are determined, I see. I have looked for you all week.”

I said, “Dad Knowles, I meant what I said when I told you that where I came from, men only marry one woman, and Maxine is my wife. Now and always.”

“Well,” he said, “don’t think I can’t have it annulled. But you have been together a week now so tell Maxine to come home and get the rest of her clothes and belongings. What has she done for clothes this week?”

“She had all week’s clothes on her last Sunday night when she left.”

Then Dad Knowles reminded me, “You don’t have a job and I don’t know what you will do when your rent comes due. I have worked for the Santa Fe Railroad shops for several years and I can probably get you on there.”

I said, “Thanks for your interest, but it would not be right for me to rely on you. I can make it on my own. I may not make much money, but I can always find work and I will.”

Lois Maxine Knowles Woods, daughter of Clarence Lemon Knowles and Lillis Leola Cross, was born in Wichita on February 1, 1922, and died in Santa Anna, California, on June 18, 1949. She was survived by her husband, James Bertram Woods, and six children: James, Jerry, Joyce, Richard, Alfred and Clifton. James, her husband, son of Bertram Francis Woods and Edith Victoria Wilbur, was born Newton, Kansas, on May 17, 1919, and died in Phoenix, Arizona, on June 23, 2012. He was 93. All six children are still living.

So how did the photograph wind up in Loot, the store in Turners Falls, Massachusetts? I talked to John McNamara, co-owner with Erin MacLean. He told me that he is constantly hunting for stuff at estate sales and yard sales. At one local yard sale, he found dozens of prints of vintage Associated Press photos. The seller said that he had an uncle, Charles Krigbaum, who worked for the Syracuse Herald (NY), and collected AP prints which the newspaper no longer needed. The prints were passed along to family members when Charles died in 1972, eventually winding up McNamara’s hands.

According to Krigbaum’s obituary, published in the Herald, he was born in 1879, in Pennsylvania, and began working in the Pennsylvania coal mines when he was 10 years old. As a young adult, he went into business with his uncle, managing a photography studio. A musician (cornet), he moved to Syracuse in 1918, and played with various orchestras and bands. In 1935, when the Herald first acquired the Associated Press Wirephoto service, he worked as a wirephoto operator, retiring in 1955.

Serendipitously, 42 years after he passed away, one of the prints in his collection is now owned by the Woods children.

*Story published in 2015.