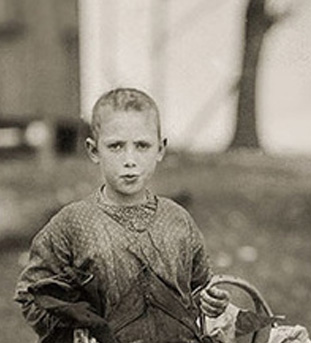

Lewis Hine caption: Sadie Kelly, 11 years old, picks shrimp for the Peerless Oyster Co. Picked 7 pots yesterday, 5 pots today at 5 cents. Picked last year. Location: Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, March 1911.

“On my father’s side, about once a month, one of his siblings would throw a party, and there would be music. My mother loved to get up and dance and wave her arms around. She always had a happy attitude. She never seemed to be down in the dumps.” -Robert Dillman, son of Sadie Kelly

Hine’s photograph is a haunting work of art. Because his camera had a very slow shutter speed, he was forced to pose his subjects, since any movement would create a blurred image. Although she is standing still, Sadie looks as if she had just noticed him and abruptly stopped in her tracks. She might have been on her way to work, or on her way home. Hine captured her alone, making her look vulnerable, as if he were viewed as an intruder. But there is one more reason why the photo is so powerful, for which Hine cannot claim credit. It is Sadie herself, her piercing eyes and the resolute, perhaps defiant way she stares at the camera. What was she thinking at that moment?

According to the Hancock County (Mississippi) Historical Society, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, there were two well-known seafood canneries in Bay St. Louis: G.W Dunbar Sons, and Peerless Oyster Company, where Sadie Kelly worked. Peerless opened in 1904. Its president, Charles H. Torsch, lived in Baltimore, Maryland, where he also owned a cannery. The cannery in Bay St. Louis provided workers with furnished barracks, which were located on Felicity Street, across North Beach Blvd from the factory.

At 3:00 am, workers were summoned to work by a shrill whistle. Shrimp pickers and oyster shuckers had to endure long hours, mostly while standing. Before adequate child labor laws existed in Mississippi, some of the workers were as young as three. That is why Hine showed up at the cannery in March of 1911.

The following are excerpts from a report written by Lewis Hine, and submitted to the National Child Labor Committee:

“I visited the Peerless Oyster Company, Bay St. Louis, Miss. I found only half a force working, about 60 in all, and 15 of these I judged to be under twelve, some from three or four years up. The photos and labels show them and give the data. One flash was all I could get inside. Then, just as I had them all ready for a snapshot outside at noon, along came the manager with an idea that the children ought not to be photographed as it might cause trouble, so I had to wait until he had gone home before I could get to the youngsters. Took some good pictures around the houses in the afternoon.”

“Here and elsewhere, I found considerable complaint about sore fingers caused by handling the shrimps. The fingers of many of the children are actually bleeding before the end of the day. They say it is the acid in the head of the shrimp that causes it. One manager told me that six hours was all that most pickers could stand the work. Then the fingers are so sore they have to stop. Some soak the fingers in an alum solution to harden them. Another drawback to the shrimp-packing is the fact that the shrimps have to be kept cold all the time, to preserve them. It would seem that six hours or less of handling icy shrimp would be bad, for the children especially.”

Mississippi passed a law in 1908, which made it illegal for factories to hire children under the age of 12, and limited work days to no more than 10 hours, and no more than 58 hours a week. It was common practice for factory owners to hire children because they could pay them less for tasks which they could learn relatively easily with a minimum of practice. Supporters of the 1908 law believed it would allow children under 12 to attend school regularly.

But when Lewis Hine investigated child labor in Bay St. Louis, Biloxi and Pass Christian, Mississippi in 1911, he found that the law was being ignored by the owners of the canneries. In 1914, a new state law was passed, which raised the age limit for girls to 14 years, kept the limit for boys at 12 years, and limited work to no more than eight hours a day and 48 hours a week for boys under 16 and girls under 18. But when Hine returned to the Mississippi Gulf Coast in 1916, he photographed children as young as seven working in the canneries. He noted that very few were attending school.

***************************

A search of the census came up with a Sadie Kelly, born around 1900, living in Pass Christian, Mississippi in 1920. The census was enumerated in January, at the height of the canning season. Pass Christian is just a few miles from Bay St. Louis. The parents, William and Cora, and all of the children, were born in Maryland, except for a 9-year-old girl who was born in Mississippi. Both the parents and at least three of the children (including Sadie) were working in a canning factory. It was common in the early part of the 20th century for Gulf Coast canneries to recruit workers from Baltimore, so I searched for the family in Maryland and found them in the 1900 census, living in Fallston, about 20 miles north of Baltimore. Sadie (listed as Sarah) was six months old, and had six siblings. Her father was a farm laborer. The two oldest children, 9 and 7, attended school.

In the 1910 census, the year before Hine photographed Sadie, the family was living in a rented apartment in Baltimore, now with three more children. Sadie was 10 years old and attended school. The family did not appear in the 1930 census, but they were in the 1929 Baltimore City directory, the father’s occupation listed as a foreman.

In the 1940 census, Sadie was no longer with her parents. But I found a Sadie Dillman in the 1940 census in Baltimore, 39 years old, and living with husband George and an 8-year-old son named Robert. Could this be the same Sadie? I searched Ancestry.com and found Sadie Dillman’s death record (July 1979 in Baltimore), and then discovered a family history posting that included some information about Sadie Dillman, including Kelly as her maiden name, and the same date of death. Using Google, I found a phone number for Sadie’s son Robert, now living just over the Pennsylvania line from Baltimore. I called him, and he was the right person. He knew nothing about the photo of his mother.

I interviewed son Robert and Robert’s son George.

Edited interview with Robert Dillman, son of Sadie Kelly. Included is a comment at the end from Robert’s wife Dolores. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on March 30, 2016.

Manning: When were you born?

Robert: September 1, 1931

Manning: Was your mother named Sadie or Sarah?

Robert: Her full name was Sarah Rebecca Kelly, but she was always called Sadie.

Manning: Where were your parents living then?

Robert: Baltimore.

Manning: Was your mother working then?

Robert: No. She was always a stay-at-home mom.

Manning: What was your father doing?

Robert: He worked for a company called Tindeco (Tin Decorating Company). They manufactured items like canister sets, step-on trash cans, bread boxes and such. He eventually worked his way up to management.

Manning: When were your parents married?

Robert: February 12, 1929.

Manning: How many children did your parents have?

Robert: Just me.

Manning: What do you think of the picture of your mother?

Robert: Amazing. Words can’t describe it. I never knew what she looked like at that young age.

Manning: You might have noticed that she doesn’t have much hair.

Robert: Yes. I think that was because she had a problem with lice, which was common then. She had to have her head shaved.

Manning: When I called you the first time, you told me that you knew that she had worked in the seafood canneries in the Gulf States as a child.

Robert: Now and then, she would mention that in a conversation. She would say, ‘My father would take all of us down to Mississippi, and we would work there.’

Manning: Did she describe what it was like?

Robert: My son George, who was very close to her, did some research on my mother, and he said in his notes: ‘She told me that they got up early, at 3:00 am, and sometimes would catch a ride in the back of a wagon that was delivering milk, so they would not have to walk all the way to the factory. The factory had a 3:00 am whistle that went off to wake up the workers in town. She told me that she made about three to seven cents a day working 12 hours.’

Manning: Lewis Hine took some pictures of some of the housing for the migratory workers, and they were very near the canneries. They looked very shabby. Since they managed to get rides in the wagon, perhaps they didn’t live in that housing.

Robert: I don’t know anything about that.

Manning: In the 1910 census, she is living in Baltimore with her father William, and mother Cora. Did you know them?

Robert: I knew Cora, but William had already died when I was born.

Manning: In 1910, they were living on West Glover Street. Mr. Kelly was a driver for a coal company. They had 10 children then. Sadie was the sixth oldest.

Robert: I only remember a few of her sisters and brothers.

Manning: Do you remember anything else that your mother said about working at the cannery?

Robert: No. Of course, back then, what she said probably didn’t interest me.

Manning: Did your mother go to school?

Robert: Yes, she said she went up to the fourth grade. My father only went up to the sixth grade.

Manning: In the 1940 census, you and your parents were living at 2804 Mayfield Street.

Robert: Yes. They owned it. They paid something like $2,700 for it. It was a single-family house in an area known for row houses, one connected to the next.

Manning: The ones that were famous for their white steps?

Robert: That’s right. My wife grew up in that area. That’s how I met her. She was out scrubbing the white steps one day when I walked by.

Manning: What was your mother like?

Robert: She was very cheerful, outgoing, a good mom and a good housewife. She was also a good penny-pincher. I’ll give you one example. My father would say to her, ‘I think I’ll need a new car next year. We’d better start saving some money.’ So my mother would start putting a dollar away every time she could until the time came to buy the car. They always paid in cash. My son wrote this down: ‘When I was young, she always told me that whenever I got some money for a gift, or made money working, I should always save, because I never knew when I would need it.’

Manning: Did you graduate from high school?

Robert: Yes, but I didn’t go to college.

Manning: What was your occupation?

Robert: I was a machinist. I started an apprenticeship in 1950, at Bethlehem Steel, in Sparrows Point (Baltimore County). I worked there for about 15 months, and then I joined the Navy. I spent four years in the Navy. At that time, if you were an employee of a company, they would take you back when you were discharged. I went back and worked for them about 35 years, and then retired. I worked my way up to a first class machinist.

Manning: Did your mother have any hobbies or other things she liked to do?

Robert: One thing she did was to make catsup for my father. They would go out and buy a bushel basket of tomatoes. He saved a lot of beer bottles, so she made the catsup— he liked it hot — and filled the bottles. They even had a capping machine. During WWII, my mother had a victory garden. She loved to travel. I used to have a little pop-up camper, and she and I would go on a weekend up to one of the state parks. One year, I was entitled to 13 weeks of vacation, so with my little camper, the whole family, including my mother, drove all the way out to California and back.

Manning: How did your mother do?

Robert: She loved it. Wherever we would camp at, she would walk around the campsite and enjoy the exercise. It we decided to drive into town to see what was going on, she would come along. If we went to a theme park, she would come along. Sometimes she would get on one of the rides.

Manning: What else did she like to do?

Robert: On my father’s side, about once a month, one of his siblings would throw a party, and there would be music. My mother loved to get up and dance and wave her arms around. She always had a happy attitude. She never seemed to be down in the dumps.

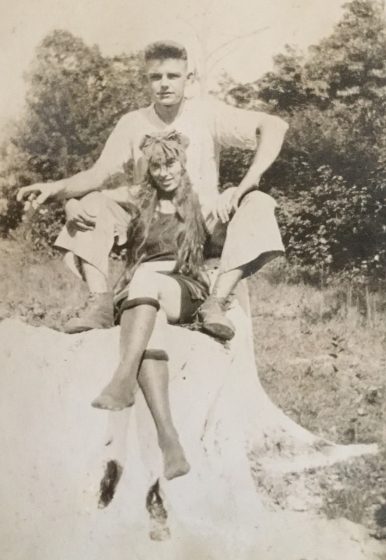

Manning: In one of the photos of her that you sent me, she looked very nicely dressed. Did she like to dress fashionably?

Robert: Let’s put it this way. She dressed carefully. What I mean by that is that she was very particular about how much she paid for clothes. When she lived with us in her later years, she would take a bus and go down to an area called Highlandtown. There was a store down there that wasn’t expensive. She would come back, and I would say, ‘Mom, did you buy anything?’ She’d say, ‘No. I looked at a dress and it was $10!’ She was tight on the money. I give her credit for that, because when my parents died, they left me a lot of savings bonds.

Manning: When you were growing up, did you often go downtown to the Howard Street area and shop at the big department stores? I grew up near Baltimore, and my mother and I used to do that.

Robert: Yes, especially the day after Thanksgiving. She would take me to the toy section of all those stores so she could get an idea what I would like for Christmas. We would eat at one of the lunch rooms at those stores.

Manning: When did your father die?

Robert: In 1965. After that, my mother lived with us, until she passed away about 12 years later.

Manning: Was she in relatively good health in her later years?

Robert: Yes, up until about 18 months before she died.

Dolores: I sat there and cried when I saw the picture. I am absolutely shocked to know how horrible those conditions must have been. When she was just a little girl, she only made pennies a day for such hard work. Imagine that; 11 years old and working. My God, what that poor family had to go through. I think it’s a miracle that she made it to 78 years old. I mean, who had good health care way back then? But up until her last year, she looked great. I thought she was going to live to be a 100. She didn’t have much education, but she persevered.

Edited interview with George Dillman (GD), grandson of Sadie Kelly. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on June 16, 2016.

JM: When were you born?

GD: 1959.

JM: How old were you when your grandmother died?

GD: I was 21. I was in college then.

JM: What kind of a relationship did you have with her?

GD: We were very close. My dad was an only child. I was about five when his father, my Grandpa George, died. I was named after him, so I was ‘Little George.’ I was her only grandson. About a year after Grandpa died, Grandma moved in with us. I was the first grandchild, then less than a year after I was born, my twin sisters were born, so there were three little children in the house. Then Mom went to work, so Grandma helped a lot with the child care, and cooked a lot of our meals. She never learned to drive, so she always took the bus when she needed to go shopping or run errands.

Every couple of weeks, she and I would get on a bus and go to Highlandtown Market and shop. Then we’d go to lunch at the White Coffee Pot, and I’d get a grilled cheese and French fries. Shortly after she moved in with us, we bought a travel camper, and the whole family took weekend camping trips. She had a hand-stitched, soft-clothed pouch, which she pinned inside her brassiere. That’s where she kept her ‘big’ money. When I got my license, she bought me a car, and I drove her to places she wanted to go. She went to Mass every week, and I went with her.

JM: What did she tell you about working in the canneries?

GD: She told me that she and her siblings — I don’t remember her referring to either parent working with them — had to go to work at 3:00 in the morning, and that she was paid about seven cents a day. But she never expressed any kind of discontent or disappointment that she was subjected to that as a kid. She just said that it was hard work during hard times. She told me that it was always important to save money. If I had a job and made some money, I needed to save as much I could in case I lost the job or had some kind of emergency. And if I got some money for my birthday, I should put it in the bank.

JM: What’s the difference between hearing her stories about working in the canneries, and then seeing the photograph?

GD: When I looked at the picture the first time, I knew right away that it was Grandma. It was such a haunting and soulful picture. I just sat there and wondered what might have been going on in her mind as a little girl. What you see in that picture is a basket and a straining pot. That pot went back and forth with her every day. If she lost that pot, she probably would have to work a whole week just so she could buy a new one from the canning company.

I think about that now, and I can hear her say to me: ‘When you get a new piece of clothing, take care of it, George. Don’t drop it on the floor. If you do, pick it up, fold it, hang it up, or put it back in the drawer. Take care of it and it will last a long time and look nice. Don’t be wasteful. Every time you spend a nickel or a dollar on something, that’s money you had to work hard for.’

JM: Do you still obey that principle?

GD: Yes, I do. I’ve tried to instill that in my three children.

JM: How old are they?

GD: 26, 24, and 17.

JM: Have you shown them the picture?

GD: Yes, to the two youngest ones.

JM: What was their reaction?

GD: They were almost non-responsive. It seemed to have no impact. For them, it’s just another old picture. Perhaps they will take an interest when they are older.

JM: Did you know much about the issue of child labor when you were growing up?

GD: Not really. When I was in high school, I probably got exposed to it a little in my history classes. But I don’t think I connected that with Grandma.

JM: Your grandmother apparently had only a third grade education.

GD: That was the only thing she resented. It limited her comprehension and her ability to read and write. A lot of times, she would get a letter from Social Security, or her bank, and I or my dad would read it for her. She emphasized to me to study hard and get a good education. I did. I went on to get a Master’s degree in Geology.

Because she had such a simple childhood, a simple existence, Grandma never really aspired to anything above that. She was a wife, then a mother, and then a grandmother. I don’t remember any conversation with her where she mentioned that she wished she could have traveled a lot, or done anything else like that. But she was not a bitter woman. She was a very pleasant person. And she had a clear sense of what was right and what was wrong.

I’d like to say one more thing. I came here to Texas to work. I am an oil and gas geologist. It’s been my profession for 30 years. For almost 10 years of that time, I was living in the far west town of Midland. Now I live about 30 miles southwest of Houston. No matter where you are in this state, you hear a lot of discussions about the immigrant families that came here and settled on land in the 1800s. Over generations, they expanded their farms and ranches. Owning that property meant that they owned rights to the minerals underneath. That created an incredible amount of wealth for a lot of those old families. I am talking about hundreds of millions of dollars for some of them. I could say to myself, ‘I wish I could have been born into a family like that.’ But when you sent me this picture of my grandma, I said to myself: ‘I wouldn’t trade her image for all of that money and all of that property. Her image helped to change our society for the better. That’s all the wealth I need.’ That’s what I see when I look at that picture.

A final note about my research for this story:

Before I found Sadie and her family, I found a different Sadie Kelly in the census who lived in Baltimore at the same time. She was born about 1897, which would have made her 14 years old in the Hine photo, not 11 as the photographer stated. Nevertheless I did some research and found a granddaughter, who lives in Delaware. She was born in 1944. She told me that her grandmother died several years before she was born. She also said that no one in her family had ever mentioned that her grandmother had worked in a seafood cannery in the South. She sent me the only photo she had of Sadie, which appeared to have been taken around 1935. In that photo, she bore no significant resemblance to Sadie in the Hine photo. I interviewed the granddaughter anyway, and then did some more research, and that’s when I found the Sadie in this story.

When I found her son Robert and sent him the Hine photo, he recognized his mother. He sent me some photos of her as an adult, but didn’t have any of her as a child. I saw a strong resemblance to the Sadie in the Hine photo right away, but I felt that I needed an expert opinion. So I sent the photos to Maureen Taylor, a nationally-known genealogist and photo identification expert, who has helped me in the past. She fully agreed with me, remarking, “Same eyes and expression.”

*Story published in 2016.