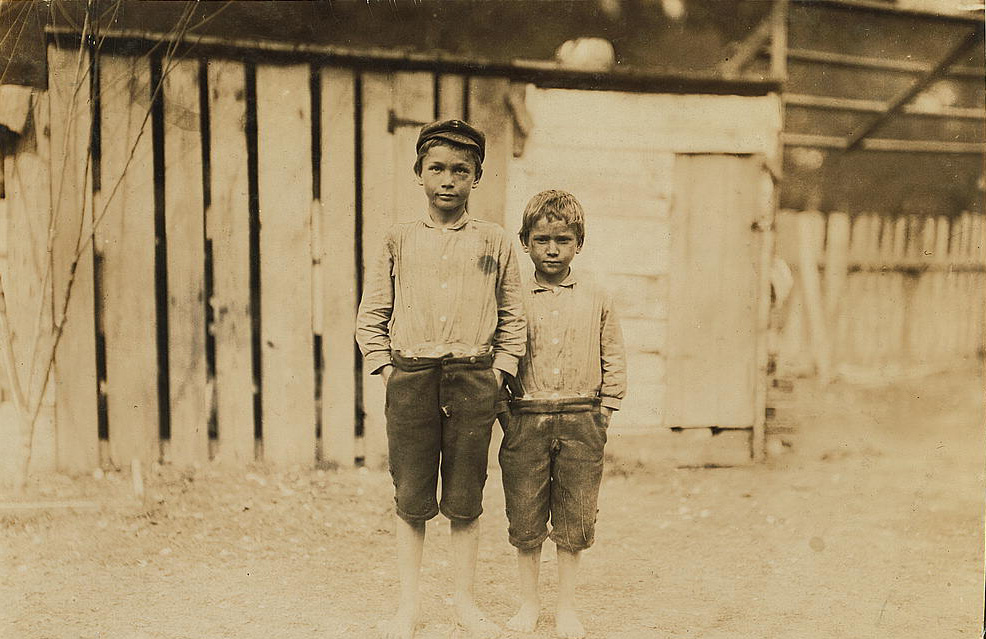

Lewis Hine caption: Joseph Velcich[?], seven years old. Beginning to pick shrimp for Peerless Oyster Co. Location: Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, March 1911.

“My father once said: ‘People talk about the good old days, but Joann, there never were any good old days in my childhood. I don’t ever want to go back to those days.’” -Joann Saucier, daughter of Joseph Velcich

In early 1911, Lewis Hine was sent by the National Child Labor Committee to the Gulf States to investigate child labor in seafood canneries. One of the states, Mississippi, had passed a law in 1908 which expressly prohibited children under the age of 12 from working in factories, including canneries. But it was common knowledge that the law was not being enforced, and that few of the children were regularly attending school.

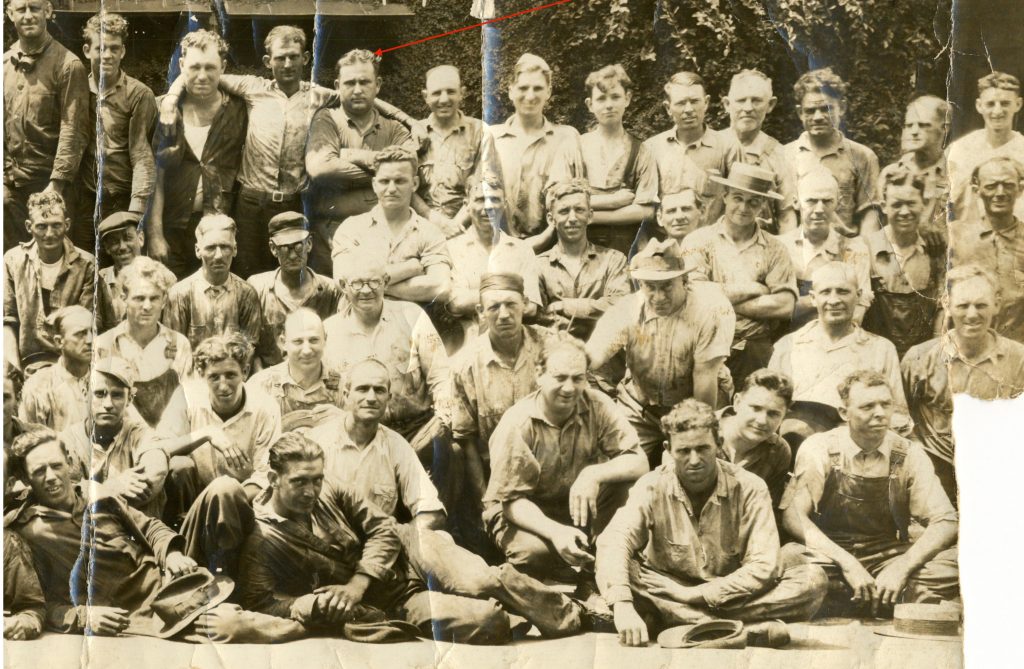

Hine took about 75 pictures at the Mississippi canneries, confirming deplorable working and living conditions, and multiple age violations. The following captions are representative of what he found in Bay St. Louis.

“Shrimp-pickers in Peerless Oyster Co. Photo taken just as they stood. On other side of the shed, still younger children were working. Out of sixty working (only half were there) I counted fifteen apparently under twelve years old. Some three, four, and five years old were picking too. Parents acknowledged ages and fact that they worked some. Boss said they went to work at 3:00 A.M., and would quit about 3 or 4 P.M.”

“A group of shrimp pickers in Peerless Oyster Co., working during the short noon recess. Many workers, including the children, utilize part of the lunch time this way, when there is a lunch time allowed. In many canneries, they snatch their lunches as best they may while the work goes on and others are getting ahead of them.”

“All these pick shrimp at the Peerless Oyster Co. I had to take photo while bosses were at dinner as they refused to permit children to be in photos. Out of 60 workers, 15 were apparently under 12 years.”

“St. Joseph’s Academy. The assistant to the Father in charge told me that none of the cannery children attended the academy, although he admitted that most of them were Catholics.”

“Maud Daly, five years old. Grace Daly, three years old. Pick shrimp at the Peerless Oyster Co. Their mother said they both help. Their sister said the little one was the fastest. Many other little ones like them working here.”

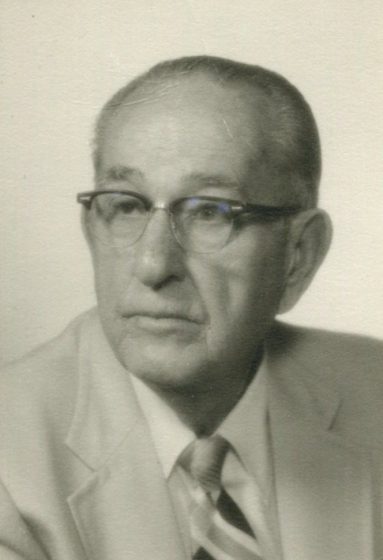

Among Lewis Hine’s many talents as a documentary photographer was his uncanny ability to spot a memorable and unique face that could generate sympathy and radiate common dignity. Joseph was no exception, and as soon as I saw him, I couldn’t wait to get started on my research. Luckily, I had no problems locating his death record and obituary, which led me quickly to two of his children, Jane Primeaux and Joann Saucier. I interviewed both of them.

Joseph John Velcich was born in Lakeshore, Mississippi (near Biloxi) on January 12, 1904. His parents, James Velcich and Mary (Martinolich) Velcich, were Croatians born in Austria. James immigrated to Louisiana in about 1883, and married Mary in 1891, the same year she arrived in the US. They had at least nine children.

When he was about 10 years old, Joseph moved from Bay St. Louis to New Orleans (60 miles away) to live with his maternal grandmother. According to the census, he later reunited with his parents, with whom he was living in 1920, in New Orleans. He married Marie Germaine Baudot in 1927, but she died shortly after their first child was born. In 1934, Joseph married Marie’s sister, Leona Marguerite Baudot. They had three children, the first dying in infancy.

Leona died in 1985, and Joseph died on January 28, 1989, at the age of 85.

Edited interview with Jane Primeaux, daughter of Joseph Velcich. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on April 19, 2016.

Manning: When did you discover the Lewis Hine photo of your father?

Primeaux: It was about 12 or 13 years ago. One evening, my husband said, ‘Why don’t you Google my name and see if I’m on Google?’ So I did. He is quite prominent here is Tulsa, where we have been living for over 20 years, so a lot of things about him popped up. So then I Googled my name, and the only thing I found were things that included my husband’s name. So then I Googled my maiden name Velcich, and I came across a picture of two young boys. In the caption, it said that one of the boys was John Velcich, and that his hands were bleeding and blistered from working in an oyster and shrimp cannery. And then I saw another picture of a little boy by himself walking down the road. The caption said Joseph Velcich, with a question mark next to it, so I clicked on it and I burst out crying. As a man, my father always told us how poor his family was and that he and his brothers worked at this place. But that was him telling me as a man, and me knowing then that he had turned out fine. But there I was, looking at this picture of him as a little boy. He was the same age as some of my grandsons. I just couldn’t stop crying.

I immediately called my sister Joann, who lives in Florida. She got on her computer and Googled the same thing and found the pictures, and then she started to cry. We knew that our father had done this as a boy, but it still hit us in the face. He told us that he only went as far as the 4th grade, but we are realizing now that he probably did not get any decent schooling at all. I believe the children were pulled from work and the education was done at Peerless. Even now, when I tell people about it, I cry. I guess we take so many things for granted. I mean, he was such a good provider for our family. I certainly didn’t live that kind of life when I was a child. And my children and grandchildren haven’t either.

I told Joann that I was going to talk to you, and she reminded me that our father only worked at that cannery till he was 10 years old. His parents apparently couldn’t afford to keep him at home. I guess he wasn’t making enough money as a kid. So he was sent to New Orleans to live with his maternal grandmother, who had a bar and restaurant in New Orleans. He worked for her in the restaurant, probably cleaning floors and washing dishes, and things like that.

Manning: Did he see his parents very often?

Primeaux: I don’t know.

Manning: When you look at these photos, do you ask yourself, ‘How could he have achieved all the things he achieved having started out like that?’

Primeaux: Yes. He had little or no education. He had four daughters, one that died shortly after birth. But all three of the other daughters graduated from college. And the oldest was born with cerebral palsy.

Manning: Which colleges did they attend?

Primeaux: Marie Audrey, the oldest, the one with cerebral palsy, graduated from Sophie B. Newcomb College. The college no longer exists. It was the female counterpart for Tulane University in New Orleans. Joann, the next oldest, was a Dominican Nun for 10 years. She graduated from St. Mary’s Dominican College (New Orleans), and then earned a Doctorate in Education from the University of Tennessee. I have a degree in Elementary Education from the University of New Orleans. I got married after my first year of college, and had my first child right away. We lived with my mother and father for a few years while my husband and I attended college.

Manning: Where was your father born?

Primeaux: Lakeshore, Mississippi (near Biloxi).

Manning: What were his parents’ names?

Primeaux: James S. Velcich and Mary Maria Martinolich. Ironically, my father always said that his parents were from Austria, but I have a grandson who was doing a research paper on our family history, and he came across information that said they were Croatians.

My father’s first wife was Marie Germaine Baudot. They were living with his wife’s parents when their only child, Marie Audrey, was born. His wife died a month later. My father continued to live with her parents, and they helped raise his child. A few years after that, he married his deceased wife’s younger sister, Leona, who is my mother, and the mother of Joann.

Manning: Where were your parents living when you were born?

Primeaux: I was born in 1942, and lived in New Orleans in a house they built shortly before I was born. It’s still there, at 2561 Jonquil Street, in the Gentilly neighborhood.

Manning: Did you live in that house for all of your childhood?

Primeaux: Yes. We sold that house after my father died in 1989.

Manning: Where did your father work when you were growing up?

Primeaux: Before I was born he was a machinist for a company called Jahncke Dry Dock. I don’t know exactly how long he worked there, but by the early 1940s, he owned a barroom in New Orleans on Canal Street near the river and the train station. It was called Joe’s Jungle. He made a lot of his money from what he was not supposed to do. He had the largest handbook on the horses in the city at that time. He was a bookie, in other words. I have a picture of him in the barroom, which was downstairs. He had poker tables upstairs.

Manning: What kind of a neighborhood did you grow up in?

Primeaux: It was a very nice neighborhood. You would not call it a wealthy neighborhood, because the wealthy neighborhoods were around St. Charles Avenue, and uptown. My neighborhood was a bit like the suburbs. My oldest sister went to the neighborhood public schools, but my other sister and I went to the Catholic school in the neighborhood. In high school we went to Dominican High School on St. Charles Avenue. My mother volunteered in the cafeteria of our elementary school. She was a ‘Friday Lady.’ My maternal grandparents lived in the house with us. My father had two sisters that lived a couple of blocks away. He had two other sisters in New Orleans that lived further away. He also had a brother that lived a couple of blocks away. His name was John. His oldest brother, Jake, lived in Pascagoula, Mississippi. He owned a seafood restaurant called Evangeline’s. My father had a sister in Mississippi that owned a grocery store. One of his sisters and one brother worked for him. The story is told that he had a sister who was so smart, that all the siblings pooled their money and sent her to college, and she wound up being a principal in a public school in New Orleans.

Manning: Your father had a barroom, so did that mean he wasn’t home in the evening?

Primeaux: No, he was always home in the evening. He had a long, loyal employee, a man who was not married. My father, without an exchange of money, made him a partner in his business. He ran the bar in the evening until closing time. The bar had several locations at different times. They were always on Canal Street, by the river. There was a lot of foot traffic there, like longshoremen, people getting off the train, and so on. He did a tremendous business in cashing checks for longshoremen.

Manning: What was your father like?

Primeaux: He was very generous. For the longest time, back in the time that milk was delivered to your door, he would always get two milk bills. I asked my mother why and she just told me it wasn’t any of my business. But when I got older, I found out that there was a longshoreman who had died, and for years, till his kids were adults, my father paid the family’s milk bills.

My father was a big sports fan. There were a great deal of youth baseball teams that were managed by the New Orleans Recreation Department. During the 1950s, my father sponsored a team in every age group from Pee Wee all the way up to semipro, and provided the uniforms, with Joe’s Jungle on the back. My sister Joann and I went to most of the games, and so did my father.

Manning: Could your father read and write pretty well?

Primeaux: His penmanship was not good, but he could read well. He was also very good with numbers. I think that’s one of the reasons why he was so successful financially. But still, my father always felt he was inferior around educated people.

Manning: What was your mother like?

Primeaux: People would say that my mother was a saint. She did a great job raising Marie Audrey, my sister with cerebral palsy. Doctors had advised my parents not to send her to school. But my mother didn’t take that advice. She walked her to school every day, walked back home, walked to school at noon to help her eat her lunch, walked back home, and then when school was over, she would walk again to get Marie Audrey and walk her home.

Note: Marie Audrey died in 2008 at the age of 79. According to her obituary: “Audrey’s biological mother died when she was only one month old. Her adopted mother, Leona Baudot, raised, nurtured and inspired Audrey and helped her overcome the many obstacles that she faced with cerebral palsy. Audrey graduated from Sophie B. Newcomb College. Because of severe hearing loss, Audrey lip-read the professors’ lectures and on the weekend her mother would hand copy notebooks loaned by students. She retired from New Orleans Recreation Department after 20 years.

Manning: When did your mother die?

Primeaux: 1985.

Manning: Was your father in good health in his last years?

Primeaux: He was in poor health then. He had an enlarged heart. He died in January of 1989. My husband and I were living in Arlington, Texas at that time. We had moved there from New Orleans in 1981. My father, mother and sister continued to live in New Orleans. Three years after my mother died in 1985, my father and sister, Marie Audrey, came to live with us. My husband loved to sit and talk with my father at night. It was only a few months after that when my father passed away. He instilled hard-working ethics in his children. I wish he could be here now to see how well we made out.

Edited interview with Joann Saucier, daughter of Joseph Velcich. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on July 19, 2016.

Manning: When you first saw the child labor picture of your father, what was your reaction?

Saucier: It was very moving, because I had never seen a picture of my father when he was younger than 20 or so. When my sister sent me a link to it on the Library of Congress website, I saw some of the other pictures of cannery workers, including the one of his brothers Johnny and Tony (Anthony). Of course, I know about child labor, and I knew my father had a very difficult childhood, but I never had any idea how bad it was. I could see the dirt from the shrimp on his hands and clothes. It was so powerful. They reminded me of what my father said once: ‘People talk about the good old days, but Joann, there never were any good old days in my childhood. I don’t ever want to go back to those days.’

He taught us to become aware of the need to help other people, because he gave so much. He was always helping people. And it wasn’t just with kids’ baseball teams. In the bar, he met so many people that were down on their luck. He would get phone calls at night from people that needed help, and he always tried to do that. He instilled in me that no matter what’s going on in your own life, there’s always somebody that has more needs that you do. He was a very magnanimous person.

He had a hard life. He had to come to New Orleans and live with his grandmother when he was a child. His first child was born with cerebral palsy, and then his wife died. His first child with his second wife died an as infant. But both of my parents had a very deep Catholic faith, and I think that is what sustained them through all the difficult things in their lives.

He wanted his three daughters to have the education they needed to become self-sufficient. He was so proud of me when I got my doctorate. When I called to tell him that I had completed my dissertation, he cried. My degree was in educational psychology. I had gotten a Master’s in Education, and was a high school counselor. But after I got my doctorate, I became a career counselor helping adults and college students to figure out what they wanted to do with their lives. I did that for quite a while until I met my husband. We decided to leave New Orleans and move to Florida, and then I got involved in the tourist business and had a very successful career in the hospitality industry.

Manning: I looked at that photo of your father at the cannery and thought about his chances of succeeding as an adult. It seemed like it would be such a long climb out of those circumstances. And then your sister told me that all three of his children graduated from college. How did you afford to do that?

Saucier: He was a successful businessman, and he would always have enough money for whatever we needed for our education. He was really ahead of his time, because so many people then wanted their daughters to just grow up, get married and have a bunch of kids. In my family, I was never under any kind of pressure to do that.

Manning: What are the things you miss most about your father?

Saucier: Just sitting and talking with him, and him giving me advice. I can just see him sitting in that rocker that he loved so much. He always listened to me. He was the perfect bartender, because he knew how to listen to people. He knew how to calm people down. He would tell them that no matter how bad things were, they would get better. He had a counseling style about him.

I’ll give you an example. After I got my doctorate, I got a job in Houston. But I didn’t like it, so I decided to leave and go back home to New Orleans. I stayed with my parents for a couple of weeks, and then my father asked me what I was planning to do. I was 37 years old, and I had no idea what I was going to do. So he said to me, ‘Let’s go look for an apartment. Don’t worry, you’ll get a job.’ So we drove around and soon found an apartment. Then he said to me, ‘Let me call Moon Landrieu.’ He was the mayor of New Orleans then. Moon knew my father well. When he was young, he had played baseball on one of my father’s baseball teams. So my father told Moon that I was looking for a job, and Moon said I should go see him. He told me he didn’t have anything full time, but he could give me a three-month job bringing together educators and business leaders in a conference about working together in the school system. It ended up lasting about six months, and I loved it. So the point I am coming to was that my father knew how to counsel people. He persuaded me to take the first step by going to look for an apartment.

Joseph Velcich: 1904 – 1989

The following editorial was broadcast on New Orleans television station WWL on January 30, 1989:

The death notice in the paper didn’t begin to tell the whole story. Joseph John Velcich, it said, a retired tavern owner, died Saturday at his home. He was 85. Is there more to this story? Yes, much, much more. Because Joe Velcich was one of the great champions of the kid athletes of New Orleans. What he did for a living was run a bar…Joe’s Jungle on Canal Street near the river. But what he did as an avocation was to promote sports for the young. Baseball, football, you name it. If you had a team and you needed uniforms, you just went to Joe’s Jungle and Joe Velcich would come up with the money to outfit the whole team. In one year he must have had a dozen of his own teams in the NORD leagues, all sporting colors of Joe’s Jungle, all wearing uniforms furnished by Joe. They say he was a sucker for a kid coach with a sad story. But it was more than that. He was a big man with a big heart and the big pockets to do what he felt had to be done. There must be thousands of young men in New Orleans…young and middle-aged now, who were able to get a team together and play in real regulation uniforms because of Joe Velcich. And perhaps, today, they will pause for just a moment, and remember, and say a prayer from the man who did so much for kids in his lifetime.

**************************

John and Anthony Velcich

Lewis Hine caption: John Velcich, ten years old, picks shrimp at Peerless Oyster Co. This is his third year at the work. Earns 55 cents a day. His hands were all sore and swelled up from the acid in the shrimp. Brother Tony, eight years old, picks some too, but is sick now. Location: Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, March 1911.

John Velcich died in 1968. I could not locate any of his children or grandchildren. I asked Joseph’s daughter Joann about him and she said the following:

“Uncle Johnny didn’t have, what you’d call, a successful life. He lived in our neighborhood for a while. He never really found himself. His personal and family life always seemed to be in a turmoil. My father always looked after him, and gave him a job in a package liquor store my father owned.”

Anthony died in 1917, at the age of 14. I was unable to determine the cause of death. His obituary appeared in the Times-Picayune (New Orleans) in March 23, 1917.

VELCICH – On Thursday, March 22, 1917, at 4:30 o’clock a. m, ANTHONY VELCICH, beloved son of James Velcich and Mary Martinolich, aged 14 years, 3 months and 17 days, a native of Bay St. Louis, Miss. The relatives, friends and acquaintances of the family are respectfully invited to attend the funeral, which will take place this (Friday) morning at 10 o’clock, from the parlors of Jacob Schoen & Son, 527 Elysian Fields avenue.

*Story published in 2016.