Lewis Hine caption: Olga Schubert, 855 Gruenwald St. The little 5 yr. old after a day’s work that began about 5:00 A.M. helping her mother in the Biloxi Canning Factory, begun at an early hour, was tired out and refused to be photographed. The mother said, “Oh, she’s ugly.” Both she and other persons said picking shrimp was very hard on the fingers. Location: Biloxi, Mississippi, February 1911.

This is one of Lewis Hine’s most curious pictures. We don’t see the girl’s face, and the mother calls her “ugly.” What are we to think? And in a second photo of her (below), we still don’t see her face, though we get a few more details.

Lewis Hine caption: Group picking shrimp at Biloxi Canning Co. Olga, five-year-old on the end was helping her mother. I tried to get her photo at home when they stopped working, but the child stubbornly refused to be taken. Her mother said, “She’s ugly.” but it seemed to me that the child could be expected to be tired out after work that began so early. Work was light and only a small crew was at work, but within an hour I found at factory and at the homes the following:…Two children of five years. One of seven years. Two of eight years. One of nine. Two of ten. Two of eleven (one had been working at this factory two years). Three of twelve, (one working here 4 years and one two years). I do not believe this is a complete list of the youngsters.] Location: Biloxi, Mississippi, February, 1911.

****************************

When I searched the 1910 census, the only Olga that showed up in Biloxi with a name similar to Schubert (which Hine put in his caption) was Subat. She was also five years old, so I knew I had the correct girl. Oddly, she did not live at 855 Gruenwald Street, as Hine stated, but at 855 Reynoir Street. Even odder is the fact that there was no Gruenwald Street in Biloxi then, nor is there one now, so it’s a mystery how Hine came up with that name. But given the unrelenting and pressure-packed nature of his investigative work, he’s entitled to a few fumbles.

Little Olga also faced work that was unrelenting and pressure packed. The following are excerpts from “Coast Canneries Are Being Probed by a Committee,” an article published in the Biloxi Daily Herald on June 23, 1913, 28 months after Olga Subat was photographed by Lewis Hine.

Shrimp and oyster canning conditions on the Gulf are being investigated by the National Child Labor Committee, an organization which has a growing membership in Mobile.

Mr. Hine found children as young as five years “plodding away all day at shrimp picking, urged on to beat the record of some other baby worker.”

“There is a prevailing impression,” he says, “that in the matter of child labor the emphasis on the labor must be very slight, but let me tell you right here that these processes involve work, deadening in its monotony, exhausting physically, irregular, the worker’s only joy the closing hour.”

He goes on to point out the hardships of work, the effect the shrimp picking on the hands of the workers. “Their fingers are attacked by corrosive substances in the shrimp that are strong enough to eat the tin cans into which they are put. The day’s work on shrimp is much shorter than on oysters, as the fingers of the worker give out in spite of the fact that they are compelled to harden them in an alum solution at the end of the day.”

Mr. Hine claims that “more efficient planning on the part of the managers and better supervision on the part of the state” would make “this exploitation of the children” unnecessary.

**************************

“When she walked into a room, you sat up straight. And you hoped she wouldn’t send a frank remark your way.” –Susan Bourgeois, niece of Olga Subat

My research, including finding Olga’s living descendants, was made much easier by the availability of the searchable archives of the Biloxi Daily Herald (from 1888-1975), which I can access through a subscription to NewspaperArchive.com. I interviewed Olga’s niece, Susan Bourgeois, who had not seen the photos.

Despite the obviously rugged conditions the Subat family faced in the early 20th century, my research indicates that they appeared to live a fairly stable and comfortable life, at least for the times. Census information, as well other information cited below, shows that Olga and most of her siblings attended school as early as the first grade. So perhaps when Hine photographed Olga, she and her younger siblings did not work regularly at the cannery.

Olga’s father, Frank, was born in Fiume, Austria. He was the son of Mateo Subat and Matitilde Paressik, and immigrated to the US in 1895. Olga’s mother Anna was born in New Orleans, the daughter of Peter Negovetich and Maria Kresich. According to Maria’s obituary in 1935, she was born in 1863 “in the Dalmatian Coast along the Adriatic Sea, then a territory of the monarchy of Austria-Hungary, now a part of Jugo-Slavia.” She and husband Peter moved from New Orleans to Biloxi in 1898. Peter was a fishing boat captain. Both sides of the family were Crotian, although they were commonly referred to as Slovenians.

When Hine photographed Olga, her parents, who married in 1903, owned a home at 855 Reynoir Street, a short distance from the cannery. In contrast, a great deal of the child laborers that Hine photographed at the cannery were seasonal migrants that lived in rows of tiny shacks owned by the cannery. An item in the Biloxi Daily Herald on April 23, 1909, when Olga was just three years old, is evidence of the simple blessings of living in a familial Croatian/Slavic community.

Miss Angelina Illich entertained a number of her friends at a birthday party yesterday at her home on Reynoir Street. Those who were present were Misses Mary Illich, Katie Rerecich, Antonia Perecich, Olga Subat, Adele Perecich, Antonia Illich, Katie Vurvich, and Masters John Rerecich, Ralph Subat, John Illich, Rudolph Perecich, Mike Illich, and Mrs. Subat. Refreshments were served.

According to the 1920 census, the Subats still owned the home. Mr. Subat owned a fishing boat, and his son Ralph, age 16, worked at the cannery. But children Olga, Gladys and Julius attended school. Two more children, Wilda and Albert, were not ready for school yet.

Six years earlier, in May of 1914, an article published in the Biloxi Daily Herald indicated that Olga had been attending school as early as 1913, when she was seven years old.

A short program at the Back Bay school marked its closing this morning at 9:30 o’clock. A short address was made by Superintendent R. P. Linfield, and he presented prizes to the pupils for regular attendance. The prizes were given by the Back Bay Mother’s Club. Refreshments were then served to the children by the ladies of the Mother’s Club. Silver medals were given the following girls for attendance: Iberia Montoli, Olga Subat, Louise Agregaard, Marie Foster, Marguerite Moran, Lucile Kennedy, Beatrice Meunier, Verna Ramsey, Cleo Trochesset, Ruth Trochesset, Louise Seymour.

According to the 1930 census, the Subat family was still living at their home, except for Olga, who was living alone in New Orleans, in a rented apartment at 1415 Saint Charles Avenue. Her occupation was not listed.

In 1940, Olga, and all five of her siblings, were living in New Orleans with their parents, in a rented house at 814 North Broad Street. Olga was listed as a manicurist. She told the census taker that the highest grade she completed in school was the eleventh. Her father Frank died four years later, after a long illness. He was 67 years old. Anna passed away in 1967, at the age of 81.

Olga died in Houma, Louisiana, on March 27, 1989, at the age of 83. She never married.

Edited interview with Susan Bourgeois, niece of Olga Subat. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on July 29, 1916.

Manning: What year were you born?

Bourgeois: 1955.

Manning: How are you related to Olga?

Bourgeois: My father, Albert Subat, was Olga’s brother.

Manning: Where were your parents living at the time you were born?

Bourgeois: Houma, Louisiana, south of New Orleans.

Manning: Your grandfather Frank Subat died in 1944, before you were born. Your grandmother Anna Subat died in 1967, when you were about 15. Did you know her well?

Bourgeois: I barely knew her but I do remember she was very nice. We would make an occasional stopover to visit her when we traveled to New Orleans.

Manning: In the caption for his two photos of Olga, Hine quoted her mother saying that Olga was ugly. How did you react to that?

Bourgeois: I think it might have been an attempt at humor. She probably felt awkward having pictures taken of her family under the circumstances. I don’t think she meant that Olga, her child, was ugly. She might have meant that she felt Olga was rude for not wanting to have her picture taken. Who knows?

Manning: What did you think of the Lewis Hine photos of Olga?

Bourgeois: I think poverty or struggles of this nature are a sad state of being. Immigrants or not, it was a time of struggle for many. Hine’s focus was on supposed child labor involving immigrants, correct?

Manning: Not intentionally. The places that Hine visited and took pictures were selected by his employer, the National Child Labor Committee, because there were reports from their field investigators that these areas had a lot of child labor. Hine took his photos from 1908 to 1917, during the time of America’s greatest wave of immigration, and during the height of the Industrial Revolution, so it makes sense that many children of recent immigrants would been have child laborers, and would have wound up in those photos.

Bourgeois: Like many in our country who faced financial struggles, I am sure they did their best to survive with the skills they knew best.

Manning: What kind of work did your Aunt Olga do as an adult?

Bourgeois: She was a nurse. She would assist people in their homes who were not able to take care of themselves in an independent manner.

Manning: What kind of work was your father doing when you were growing up?

Bourgeois: He was the supervisor of Elementary Education for the Parish of Terrebonne.

Manning: That’s quite an accomplishment, considering what his family started out with. How did he manage to do that?

Bourgeois: I would assume, being the youngest of six siblings, he might have been least affected by the early struggles, but I have no doubt that he was aware of his family’s struggle.

I think he managed it in the same manner many other men and women did of their time. He was able to grasp the importance of a solid education. He graduated from Warren Easton High School, in New Orleans. He wasn’t a large young man, but he was extremely athletic and disciplined. He played on the football team and in his senior year his team was undefeated. He, and several others on the team, were awarded full scholarships to LSU (Louisiana State University), but he was soon drafted into World War II. He was told that his scholarship would be available when he returned after fulfilling his service commitment. Upon his return he found out that the scholarship was no longer available, but in place of it, he received a football scholarship to Northwestern State University in Natchitoches (Louisiana). Believe it or not, Dad again had the honor of playing on a football team that went undefeated. Years later, after he retired, he, along with the remaining members of the team were called out at the halftime ceremonies for being a part of the only undefeated football team in its history. That night meant a lot to my dad. Dad received his undergraduate degree from this university.

He furthered his education, like many, under the GI Bill, and continued his education at the University of Colorado and later, attained his masters at Tulane University. He was married by that time with two small children as he continued to work towards a Ph.D. Due to his family expanding, he went to work full time and dropped the goal of a Ph.D.

He was later called back into the Army due to the Korean War. He was a captain, and he served under General George Patton. He would quote word for word many of the words he heard Patton recite. Dad wrote a book about his life and his experiences under Patton. It was never published, but he gave all four of his children a copy of the manuscript and a taped version.

Manning: Did your father, or any of his siblings, ever talk about working at the seafood canneries?

Bourgeois: Not that I remember. I don’t think my father was involved in life at the canneries but I am sure he heard about the experiences of his family.

Manning: You are probably correct. After all, he was born in 1918, and it’s unlikely that he would have worked at a seafood cannery, at least as a child.

Bourgeois: He did tell stories about walking around barefoot, having to wear knickers, and long, cold walks to attend school. I don’t think stories of this nature are that unusual for the time period. I think Walt Disney stated he and his brother were instructed by their father to deliver newspapers before they went to school each day, and many days had to trudge through snow. I think people did what they felt they needed to do to survive or prosper.

I see those kids in the Hine photos at the cannery, and I don’t think they were all that different from other children at that time. In those pictures, the kids are sometimes smiling. They are often with their mothers. I would assume there were no day care centers or sitters available. Men and women had to both work to survive in hard times, so their sons and daughters were at their sides.

Manning: I want to know more about Olga. What was she like?

Bourgeois: Honestly, Aunt Olga was scary. When she walked into a room, you sat up straight. And you hoped she wouldn’t send a frank remark your way. One time, one of my sisters visited Aunt Olga, and brought her son along. Aunt Olga looked at him and said, ‘He looks like a turtle.’ Now, where did Aunt Olga acquire this blunt behavior? Her mother, of course. That was just her way of talking. She was always forthright and funny. There was no outward softness to Aunt Olga, but I am sure there was on the inside. Like many Europeans I’ve known, she dressed immaculately, much like my dad. They took great pride in the clothing they wore, and they carried themselves in a proud way.

Aunt Olga never married. But she had boyfriends, from what I understand. She probably never wanted to get married. Back then, I think people that grew up in struggling families and witnessed so much strife became disillusioned. I imagine they did not look at marriage and children through rose-colored glasses. Instead of attempting to capture the American Dream, I think many settled for a small sliver of pie.

Aunt Olga lived a long life. If her goal was to become financially independent, she achieved it. She owned two homes and had accrued a large savings at the time of her death.

Manning: In the 1940 census, all six children were still living with their mother.

Bourgeois: I am sure that was not uncommon for the times with people who had experienced earlier struggles. They probably pooled their resources in order to enjoy a nicer quality of life.

Out of the six siblings, only three married. Out of the three that married, only one, my father, had children.

Out of the unmarried, one sibling, Aunt Wilda, also served in the Army and lived with her mother until her mother’s death. The remaining unmarried son, Julius, died in action in WWII. I have heard he may have been my grandmother’s favorite. My older sister told me that my grandmother never again referred to him by name. It must have been too painful. My sister said she would refer to him as ‘that boy’ when she spoke.

Manning: Olga died in 1989, at the age of 83.

Bourgeois: Aunt Olga lived outside the New Orleans area. When she experienced a stroke, my parents brought her to Houma, their hometown. I would go visit her with my youngest child, Michael. Strangely, in her peculiar state, she loved being around his sweet innocence. It makes you wonder if that softness was hidden all along. I know it was hard for Dad to see his older sister in that condition, but I think they were all there for one another all along, in spite of the difficulties of life.

I do remember that Aunt Olga made a rare visit to our home back in the 1960s. It was a time when many homeowners began to add air conditioning. She was seated at our kitchen table complaining about the summer heat. It didn’t take long before she directed her frustration at my dad. ‘Albert, I can’t believe you don’t have air conditioning in here. It’s terrible; I’m dying in here.’ She didn’t realize that my father was trying to make ends meet. He had a lot of expenses: four children, braces, and my Mom going back to college to gain her degree. By the time Aunt Olga left, she gave my dad money to purchase air conditioning window units.

I think Aunt Olga was always a nice person in disguise.

A short time after I completed the interview, I received this email from Ms. Bourgeois:

“After I hung up the phone with you I had a sudden epiphany of what Aunt Olga might have said had she witnessed our interview. ‘My God, can anyone shut her up?’”

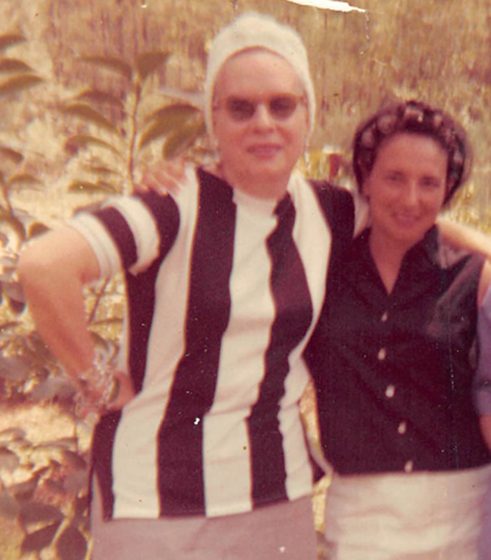

“I remember Aunt Olga as an attractive, well-dressed woman. This is a casual picture, yet she is wearing a modern striped top, a cluster of bracelets with dangling earrings to match, a turban and fashionable sunglasses. I think that she learned this from her mother. If you look at her at the shrimp table, her hair is neatly styled in a bun, she is svelte and her clothes are clean and in the best condition under the circumstances.” -Susan Bourgeois

Olga Subat: January 26, 1906 – March 27, 1989

The following article was published in the Biloxi Daily Herald on May 6, 1927. Used with permission.

BILOXI FISHERS GIVE AND OFFER

Sturdy Slavonian Fisherman of Biloxi Give Money and Offer Services and Boats to Flood Victims

Biloxi is known as a port of many sturdy fishermen, none of whom are better men and true than the Slavonians whose country emerged into nationality as a result of the war, which released them from the Austrian Empire.

But long before the war, they had been coming from the shores of the Adriatic to Biloxi, and they have become citizens and educated their children in local schools. They found good employment here for their expert fisherman’s qualities, born in them on Isle Brach and Dalmatian shores. They are very superior boatmen and own a great many good boats, which are assembled ready to go into Louisiana flood districts to succor the distressed. They know the flooded territory of Southeast and southern Louisiana, which has for years been their fishing grounds, supplying Biloxi factories.

They offer themselves and these large, roomy, powerful boats, some of which are auxiliary power sloops—they are fearless, and used to hardships of the sea.

Not only that: Captains Jake Rosetti, Tony Cvitanovich and Frank J. Baranovich formed a committee who collected $176.50 from Slavonians and those of Slavonian descent, living in Biloxi, named below. The sum was delivered to the Daily Herald relief fund yesterday afternoon.

It must be known that these men are at the end of the spring fishing season and there is no work for them till the fall and winter season, which very likely holds no promise for them because of the destruction of oysters by river water from the Poldras crevasse. In 1928 the new Louisiana law will prevent their further fishing in their old grounds in the Louisiana marshes.

With these conditions present and before them, they offer themselves and their boats; the following also contributed money:

Note: One of the contributors listed was Olga’s father, Frank Subat.

*Story published in 2016.