Lewis Hine caption: Jewell and Harold Walker, 6 and 5 years old, pick 20 to 25 pounds of cotton a day. Father said: “I promised em a little wagon if they’d pick steady, and now they have half a bagful in just a little while.” Location: Comanche County–[Geronimo], Oklahoma / Lewis W. Hine. Oct 10, 1916.

Lewis Hine caption: 5-year old Harold Walker. Location: Comanche County–[Geronimo], Oklahoma / Lewis W. Hine. Oct 10, 1916.

“He talked about helping his father in the fields. He was pulled out of school at about the eighth grade and forced to work in the fields. That was the name of the game. His father needed him to do that, so he did. However, I want you to know that he went back at a later time and finished high school.” –Lynda Baxter, daughter of Harold Walker

Lewis Hine caption: 6-year old Jewell Walker. Location: Comanche County–[Geronimo], Oklahoma / Lewis W. Hine. October 10, 1916.

“I know that if my aunt had seen these pictures, she would have been surprised that it was called child labor. And she probably would have thought it was funny. All her life she hated people taking pictures of her. –Jane Rhoads Spring, niece of Jewell Walker

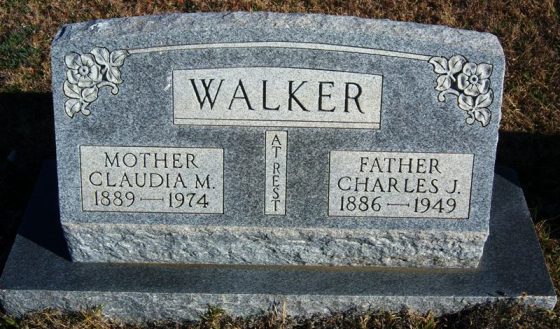

Lewis Hine caption: Family of C.J. Walker, Route 2, Box 78, Geronimo, Oklahoma. 6-year old Jewell and 5-year old Harold picks 20 to 25 pounds of cotton a day. Father said: “I promised em a little wagon if they’d pick steady, and now they have half a bagful in just a little while.” The 3-year old is learning to pick. Father is a renter on shares: gives 1/4 of his cotton for rent, and 1/3 of his corn. Has 20 acres in cotton. Location: Comanche County–[Geronimo], Oklahoma / Lewis W. Hine. Oct 10, 1916.

On the day that Lewis Hine photographed Harold and Jewell Walker and their family, it had been 40 days since the passing of the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act, the first federal law regulating child labor. The law applied to virtually all manufacturing companies, factories, coal mines and seafood canneries, but did not address the issue of child agricultural workers that worked with their parents on family farms.

When Hine traveled through Comanche County, Oklahoma, in 1916, he had been working for the National Child Labor Committee for more than eight years. His photographs were highly acclaimed as one of the primary reasons why stricter child labor laws had been passed by numerous states, leading up to the 1916 federal law. Having made considerable progress, the National Child Labor Committee asked Hine to go to Kentucky, Oklahoma and Colorado to report on the quality of life among children working on family farms, as well as non-family farms, with special attention paid to concerns such as worker safety and school attendance. The Committee wanted to establish future guidelines for how to deal with this evolving issue.

Two years later, in 1918, the federal law was overturned by the US Supreme Court; but its impact, pressure from labor unions, more stringent state laws, and increasingly modern manufacturing methods in factory work resulted in a substantial decrease in child labor.

Searching for descendants of the Walker family turned out to be a relatively easy task. I quickly found the obituaries for Harold and Jewell, which led me to Harold’s daughter, Lynda Baxter; and Jewell’s niece, Jane Rhoads Spring. Neither had seen the Hine photos.

Harold and Jewell’s parents were Tennessee native Charles Johnson Walker, and Arkansas native Claudia Mae Riggs. They married on January 10, 1909, probably in Wichita Falls, Texas, and had seven children. First child Vivian Jewell Walker (known as Jewell) was born on November 16, 1909. At the time, Charles was a lineman for the light and power company. Several years later, the family moved to Geronimo, Comanche County, Oklahoma, where Charles rented a cotton farm and became a sharecropper. Son Harold Lee Walker was born on September 5, 1911. Son William Walker (also pictured in one of the Hine photos above) was born in 1913, and died in 1957. He was an engineer and a veteran of World War II. He had three daughters.

Charles Walker died in 1949, and wife Claudia died in 1974.

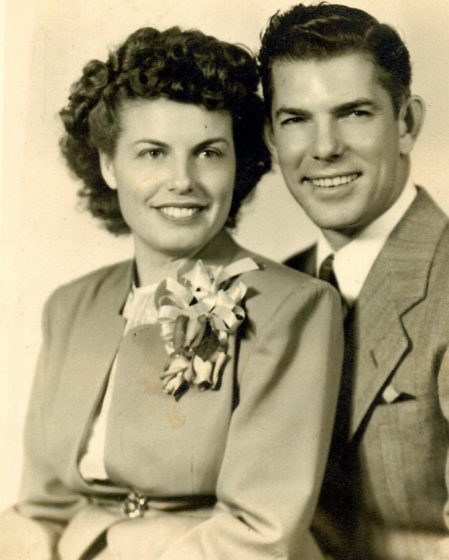

Harold was married three times: to Martha Lee in 1937, Dorothy Burgwin in 1947, and Pauline Kinney in 1989. He had one child (from his first marriage). He died at the age of 90. Jewell married Joseph Brooks, with whom she had two children. She died at the age of 94. The interviews below provide detailed information on their lives, and how they are remembered.

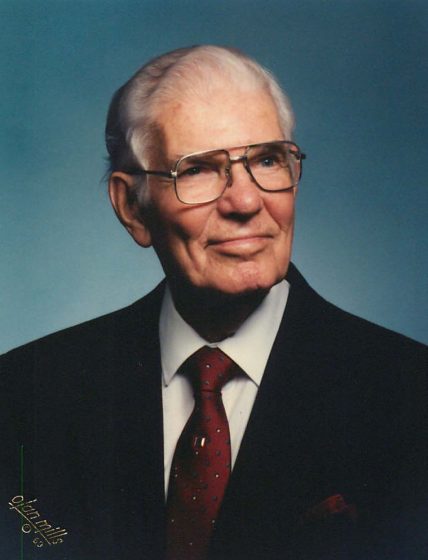

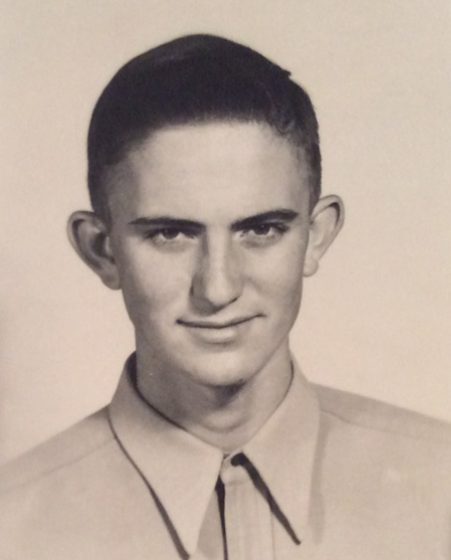

HAROLD WALKER

Edited interview with Lynda Baxter (LB), daughter of Harold Walker. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on April 7, 2016.

JM: What did you think of the photos? Were you surprised by them?

LB: Absolutely. A total shock.

JM: Did your father ever tell you that he was doing this as a child?

LB: He talked about helping his father in the fields. He was pulled out of school at about the eighth grade and forced to work in the fields. That was the name of the game. His father needed him to do that, so he did. However, I want you to know that he went back at a later time and finished high school.

JM: Do you mean that he got a GED?

LB: No, he actually attended school again. After he served in World War II, he was able to get into Cameron College, which was right there in Lawton. (Now called Cameron University, it was a two-year college when Harold attended. It is part of the State University system).

JM: When were you born?

LB: 1942. I’m the only child. His first wife, Martha, was my mother. Her maiden name was Martha Edna Lee. She divorced my dad while he was stationed in the Philippines. When he came back, he won a custody battle for me, because he thought my mother was living a life that was not appropriate. He was right, and she drifted out of our lives.

JM: Where was your father working at the time you were born?

LB: At the fish hatchery at the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, near Lawton. We also lived there. The Refuge had buffalo, deer, elk, and other animals. There were about a dozen small lakes. The last time I went back to visit when my dad was still alive, we drove out to the Refuge. My dad showed me the little prefabricated house that they lived in when I was born.

Before I was born, he worked in a local grain elevator. At some point, he injured his hands there. It stripped his hands, and the doctors told him they would have to cut off his fingers. He told them, ‘I’ll die before you cut off my fingers.’ His hands got better, although they were scarred and a little messed up. But they were my father’s hands. A couple of years after I was born, he started working at the fire station in Lawton, and then he went to the fire station at Fort Sill, about 10 miles away.

He married Dorothy Burgwin in 1947. The three of us made a little home in Lawton. He worked 30 years at Fort Sill, in the fire department, the clerical department, just about everything. He was a very dedicated firefighter, and he was the senior fire inspector.

During the Korean War, Fort Sill was the artillery center of the world. The military brought all kinds of people, equipment and weapons there. There was a lot of training going on. They had an east range and a west range. The artillery would fire across the ranges. Fort Sill was inundated with new soldiers who were training. They put my dad in Station Three, which was the training area. There were thousands of tents all over the post.

It was an incredible time. When I was six or seven, Fort Sill had the horse-drawn wagons at events. Lots of people would be there, and they would watch the wagons ride by. They would have cannons and all sorts of stuff. I loved it. I also spent a lot of time at the Wildlife Refuge. They had an annual Easter Pageant.

My dad was great. He and my stepmother were active in their church, in their community, and in the schools that I attended. I played the piano, and they were very supportive in that. They were both very upstanding people in the community. We went to the Church of Christ, and we all sang. He was very knowledgeable about the Bible. He could do most anything. If somebody was building something, or working on a car, or pouring concrete, anything, he could help them. I miss his knowledge, his demeanor, and the way he looked at things. He and I could go fishing and just experience the pleasure of being together.

I went on to high school, and sang in a cappella groups. I attended some college classes at Cameron, and then got married. My husband was an insurance adjuster. We lived in a little town just west of Lawton. Then we moved to California, where my husband had grown up. I talked to dad once or twice a week, but it was hard being that far away. But I’m still in California. I’ve been a cemetery manager for 34 years. It’s been a good experience.

In the late 1980s, my stepmother got very sick. She was coughing and really having a hard time. I told her, ‘Look, I’m going to call your doctor.’ And she told me not to. So I told her, ‘If I don’t, I’m going to lose both of you. Daddy is very concerned that you are not getting better.’ So she finally gave in, and the doctor put her in the hospital. She passed away two weeks later, in 1989.

Not long after, my father married Pauline Moore. She had been married two times before. She and my dad enjoyed each other tremendously. Dad passed away in 2001, at the age of 90, and Pauline died five years later at the age of 96.

JM: How long has it been since you were back in Lawton?

LB: Too long.

JM: If you could go back today, what was the first thing you would go and see?

LB: My dad’s grave. After that, I would spend as much time as I could at Fort Sill. It was my idea of how the world should run. It was quiet, it was clean, all the cars went in the right direction, and there was no trash on the streets. My first child was born in 1961 at the Army hospital there.

The following letter by Harold Walker was published in the Lawton (Oklahoma) Morning Press on February 5, 1977.

To The Editor:

I am deeply gratified to learn that during the week of Feb 13-19, Lawton Public Schools will observe their third Black Heritage Week.

This has worked so well in our schools in the area of reducing ethnic problems that are still troubling many schools in Oklahoma. And because of the initiative shown by this observance, the Lawton Public School administration is deserving of our appreciation.

I am looking forward to an even wider observance of “heritage” weeks in our schools that will include Mexican-American students and Indians. The result of an expanded effort will in my opinion develop an excellence in our schools that can be found nowhere else in America.

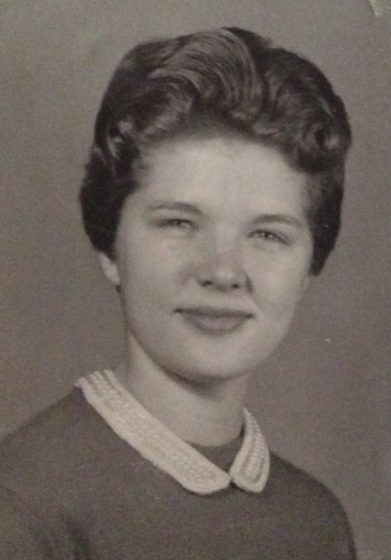

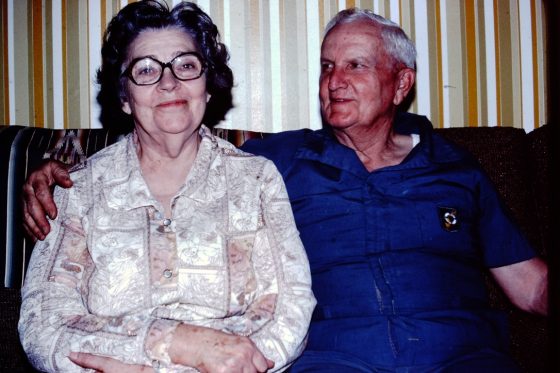

JEWELL WALKER

Edited interview with Jane Rhoads Spring, niece of Jewell Walker. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on July 6, 2016.

Manning: What did you think of the Lewis Hine photos of your aunt and his brother Harold?

Spring: Well, they were farm people, so I am not surprised that they were doing that then. But I was surprised they were in the pictures, and that they were presented as examples of child labor. It was a family thing. That was the norm. The younger children couldn’t be left in the house while the parents and the older children were out in the fields. I know that if my aunt had seen these pictures, she would have been surprised that it was called child labor. And she probably would have thought it was funny. All her life she hated people taking pictures of her.

Manning: What year were you born?

Spring: 1945. My mother was Lucille, one of Jewell’s and Harold’s sisters.

Manning: Where were your Aunt Jewell and Uncle Joe living when you visited them?

Spring: They lived in various places (in Comanche County): Chattanooga, Lawton, and in a little town near Geronimo. Both sides of my family lived within 20 miles of each other. They were all farm people. All of them had some land. They grew vegetable gardens, and had chickens and a few cows and rabbits. But they also had jobs when I knew them. Some of them worked at Fort Sill or in Lawton. One was a bus driver, one was a fireman. Uncle Joe was a rural postman. He would go to work real early, get home around noon, and do his farm work.

Manning: Did Aunt Jewell and Uncle Joe own their farms?

Spring: I think the only time that Uncle Joe and Aunt Jewell didn’t own their farm was in their early years. At one point, Uncle Joe owned a gas station, which was also their home, and they had about an acre behind their house, where they grew mostly to feed their family.

Manning: Did Jewell also work outside the home?

Spring: Before she married, she worked for a photographer in Lawton. When Uncle Joe was drafted in WWII, she went to work as a US postal clerk in Lawton. Later, in the mid-1940s, she worked briefly in a law office in Lawton. But she didn’t work after that.

Manning: Did Jewell graduate from high school?

Spring: Yes.

Manning: Why did Jewell and Joe move to Texas?

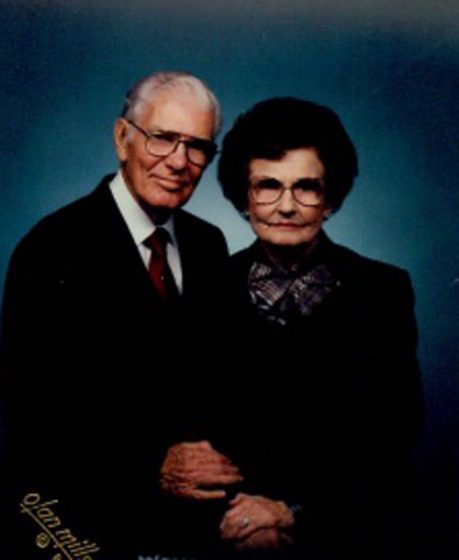

Spring: When they were older and retired, they had a little ranch near Geronimo. Uncle Joe had retired from the post office. They lived there for quite a few years and had about six acres. They had two sons. One of them, Charles, moved from San Angelo, Texas to take a job with Mobil Oil in Dallas, but they lived in Irving. So Uncle Joe and Aunt Jewell moved to Irving, and lived there until she died. At that time, I also lived in Irving, was married and had children. So I was able to see my aunt and uncle frequently again.

Manning: How many children did they have?

Spring: Two sons, Robert Don and Charles Melvin (now deceased). Robert Don, the older one, is 85, lives in Houston, and is in poor health.

Manning: What was Jewell like?

Spring: She was my mother’s sister, but she born 20 years before my mother was, so there was this big age gap. So when I would go stay with Aunt Jewell and Uncle Joe, they were like grandparents to me. I stayed with them more than I stayed with my real grandparents. She was the person I wanted to grow up to be like. She was very strong. I never saw her mad or upset. She was very even keeled and was a hard worker. Her relationship with Uncle Joe was incredible. They were always together, always loving. They were real role models for me. Aunt Jewell was good-hearted and liked to help people. She and Uncle Joe were church people. And they were funny, too.

Manning: When you visited Jewell for extended periods when you were young, what did you enjoy doing with her?

Spring: She was always cooking and putting up things from the garden, so she would teach me all about doing that, and I would help her. I would shuck corn and cut corn, and put it in little bags to freeze them. She had a cellar where she stored a lot of food. And they had a big library for farm people. I would read lots of her books. She also had a record player, and she would play a lot of music during the day.

Manning: She passed away only 13 years ago. Was she in pretty good health in her older years?

Spring: Yes, pretty much. She had health problems probably from the time she was 40. But she had an attitude about that. It was hilarious. This is a quote from her. ‘Well, when I go to the doctor, I just lie like a dog.’ She just felt like she could take care of herself. She and Uncle Joe were very independent. They might have had more health problems than I knew about. They just didn’t talk about it.

Manning: Well, they must have taken pretty good care of themselves. She lived to be 94, and he lived to be 100.

Spring: That’s right.

Manning: Did you go to college?

Spring: Yes, I received a degree in Elementary Education from Abilene Christian College, now called Abilene Christian University. I also received a Master’s in History, so naturally, I am very interested in what you are doing. I was a teacher for about 18 years, but I took time off occasionally to raise my children.

Manning: What do you miss most about her?

Spring: Probably the feeling I had when I was around her, that I was cared for, that she was always interested in me and my children. When they were older, she and Uncle Joe loved to sit around and talk and watch the birds from their windows. I miss just listening to them talk. We had a sweet relationship.

Aunt Jewell and Uncle Joe were Godly people, church people, community people, and felt like hard work was one of the blessings of life. They were satisfied with their lives. No matter what they had or where they were, they valued relationships, and they valued their children and grandchildren. They never saw anything extraordinary about their achievements, but they were extraordinary in their ability to live life, and to make it pleasurable for themselves and other people. I’ve always felt that when you have a good family, there will always be somebody around that will help you. I learned that from them.

Harold Walker: 1911 – 2001

Jewell Walker: 1909 – 2003

The following was written for a Walker family reunion in 1988, by Lucille Walker Rhoads, sister of Harold and Jewell Walker. She was also the mother of Jane Rhoads Spring, who is interviewed above.

One of the memories I have of Mom and Dad goes back 53 years to the year 1935. The incident I remember is about the Depression…about the thousands of jobless men who hopped freight trains because they had no money to travel around the country looking for work. They looked like hobos, and we saw a lot of them because the train ran through our little town of Geronimo, Oklahoma. Often one or two would get off the train near our house because they were hungry. I usually made myself quite visible because I was curious and wanted to hear everything they said. They would always ask if we had some odd jobs they could do for something to eat. Then they would wait on the back steps while Mom fixed a plate of food. More often than not it would be topped off with homemade bread and butter. I was almost 10 years old that summer and I can still recall how these people looked, their old clothes, and the humbling effect it had on each of them to have to beg for their food. Most of them were no doubt men who at one time had enjoyed better times.

Times were very hard. Wages were so low that seventy-five cents per day was sought after and there weren’t many jobs to find. Dad did have a job but there surely wasn’t much money around. We had a garden, a few cows, chickens and even pigs on the small acreage Mom and Dad owned. These provided food for us and we always had plenty. That year, 1935, Dad would turn 49 years old on September 1, and Mom had cooked one of her special dinners for his birthday. Most of the family must have been there, as well as the a few other relatives since that was generally the case. Just as we sat down to eat, there was a knock at the back door and Dad left the table to see who was there. He returned with two men, and they had obviously been riding the rails, but really didn’t look like hobos so much or like the usual unemployed. Each had a guitar slung across his shoulder and they had already asked Dad if there was something they could do to earn their supper. Dad said he would like to hear some music for his birthday, but first they were to sit down and eat with us. We found out they were trying to get down to Texas where they had jobs waiting for them in a band. I’ve wondered if maybe it could have been with the Burris Mill Light Crust Doughboys band which was becoming famous about that time for their noontime radio program.

In a little while these two strangers and two of our uncles began to play and sing all the popular songs of the day. I guess I had never heard anything like it because it surely did impress me. It was wonderful having all that lively music and seeing everyone have a happy time…Dad most of all! It was really unusual that Dad had let two strangers, who had hopped off a freight train, come into our house and eat at our table with us. Who knows what compelled him to do this, but I like to think it was an honest trust in other human beings and a confidence in his own judgment.

“Let us remember the good times with our parents, who worked hard to give us a better and easier life than they had. They wanted all of us to be honest with our fellow man and to love God and keep His commandments.” -spoken by Jewell Walker Brooks, at family reunion in 1988

**************************

In 1924, eight years after Lewis Hine photographed the Walker family and completed his investigation of working conditions for child farm workers, the National Child Labor Committee published the report below, titled Child Labor On the Farm.

The National Child Labor Committee has no intention of trying to secure any federal action to regulate the work of children in agriculture under the direction of their parents on their own farms.

The Committee recognizes that the gainful employment of children in agriculture constitutes one of the most serious phases of the problem, both because of the great number so employed and because of the practical impossibility of enforcing the usual limitations as to ages and hours of work.

We believe that the employment of children in general agriculture by their parents or guardians on the home farm differs so materially from that found in manufacturing, mining and commercial pursuits that its control and correction require different methods.

Here abuses against childhood incidental to their employment by their parents or guardians on their farms may be corrected by health, educational and other protective agencies more easily than by prohibitive legislation. Where these methods fail, and where cases of abuse, neglect, delinquency, or truancy may be traced to the employment of children in agriculture, the problem should be handled by juvenile courts and their attendant probations services, by boards of public welfare, by the public school authorities, or by citizens’ committees established for this purpose.

The National Child Labor Committee in advocating a federal Constitutional Child Labor Amendment does not understand that such Amendment contemplates or would make desirable federal legislation to prohibit the normal employment of children by parents or guardians on their own farms. On the other hand the National Child Labor Committee seeks to cooperate with all public and private educational, health and other agencies in the several states and localities organized to promote the welfare of the farmer and insure justice to children living in rural communities.

The National Child Labor Committee is aware of significant changes in agricultural practices and modes of production. In certain forms of intensive agriculture the processes have already come to resemble those of manufacturing industry. With the cumulative application of machinery to agricultural production, there is likely to occur the same tendency toward “speeding,” towards the exploitation of women and children, and toward poor housing which were the concomitant evils of the earlier manufacturing period.

The introduction of the machine sometimes leads toward a diminution of regard for the human being. The National Child Labor Committee seeks to protect the interests of the child, and it cannot remain true to its past traditions without recognition of the fact that thousands are now and likely to be in the future exploited by an industrialized agriculture. Whenever conditions inimical to the welfare of the child appear in agriculture, this Committee stands ready to reveal such conditions and to strive for their elimination or correction.

When this goal can be achieved without legislation, non-legal policies of correction will be pursued. When legislation appears to be the only means of establishing principles of general justice, this Committee will strive to create a public opinion favorable to such legislation which, under normal conditions, would probably be state or local legislation. It is now clearly evident that when children are forced to work under contract in industrialized forms of agriculture some form of legislation is needed to protect their interests. With such a policy, the National Child Labor Committee believes it has the almost unanimous support of the better farmers of the United States.

*Story published in 2016.