Lewis Hine Caption: Marie Kriss, seven years old, shucks oysters and picks shrimp at Biloxi Canning Co., when not tending the baby. Makes 25 cents some days. Biloxi, Mississippi, February 1911.

“She said that when they first came here from Baltimore, they came on a train. She said they had white sheets on the bed on the train, but they were so white and clean, that they didn’t sleep on them, because they didn’t want to mess them up.” -Sandra Beaugez, granddaughter of Marie Kriss

According to the Social Security Death Index, and her gravestone, Marie Kriss was born on October 26, 1902. That means that she was eight years old, not seven, when Lewis Hine photographed her. She and her family were among many Polish and Bohemian immigrant families living in Baltimore that commonly migrated to the Gulf States in the winter to work in the seafood canneries. But in 1910, the Kriss family chose to stay in Biloxi, and never returned to Baltimore. The following are excerpts from “Baltimore to Biloxi and Back,” written by Lewis Hine, and published in The Survey in 1913, two years after Marie Kriss was photographed.

Every year about October, hundreds of Polish and Bohemian people (some authorities say thousands) are herded together by various bosses or “padrones” in Baltimore and other centers of the South and shipped over to the coasts by train and by boat and set up in shacks provided by the canning companies. We are told by one of the canners, “We give these people all the modern conveniences.” The modern conveniences appear to be summed up in artesian wells. If there were no cold or wet weather in these parts, if waste and sewage were carried off, and if there were no crowding, these temporary quarters would be endurable; but in cold, or hot, or wet weather they are positively dangerous, especially to children. One row of dilapidated shacks that I found in South Carolina housed fifty workers in a single room house. One room sheltered eight persons, and the shacks were located on an old shell pile within a few rods of the factory, a few feet from the tidal marsh where odors, mosquitoes, and sand flies made life intolerable, especially in hot weather.

When they are picking shrimps, their fingers and even their shoes are attacked by a corrosive substance in the shrimp that is strong enough to eat the tin cans into which they are put. The day’s work on shrimp is much shorter than on oysters as the fingers of the worker give out in spite of the fact that they are compelled to harden them in an alum solution at the end of the day. Moreover, the shrimp are packed in ice, and a few hours handling of these icy things is dangerous for any child. Then, too, the mornings, and many of the days, are cold, foggy and damp. The workers are thinly clad, but, like the fabled ostrich, cover their heads and imagine they are warm. If a child is sick, it gets a vacation, and wanders around to kill time.

The youngest of all shift for themselves at a very early age. One father told me that they brought their baby, two months old, down to the shucking-shed at four o’clock every morning and kept it there all day. Another told me that they locked a baby of six months in the shack when they went away in the morning, and left it until noon, then left it alone again all the afternoon. A baby carriage with its occupant half smothered under piles of blankets is a common sight. Snuggled up against a steam box you find many a youngster asleep on a cold morning. As soon as they can toddle, they hang around the older members of the family, something of a nuisance, of course, and very early they learn to amuse themselves. For hours at a time, they play with the dirty shells, imitating the work of the grown-ups. They toddle around the shed, and out on to the docks at the risk of their lives.

MANY SCHOONERS READY TO HUNT, Biloxi Daily Herald, Aug 10, 1916

Numerous transfers have been made at the office of Lewis E. Curtis, United States deputy collector of customs, as preparations are being made to send boats out to hunt for shrimp in the Louisiana marshes. The shrimp season has begun, and if favorable weather prevails, there will be a rush to the shrimping waters during the next few days. Transfers to date are as follows: Schooner Reginea Edna, Frank Borchanovich endorsed as master; Schooner Evelyn Desporte, Vincent Gaspodinovich endorsed as master; Schooner Marvel, Sam Marinovich endorsed as master; Schooner Comanche, Peter Wescovich endorsed as master; Schooner American Girl, Joe Kriss endorsed as master.

When Joseph Frank Kriss headed out on the American Girl to hunt for shrimp in the Louisiana marshes in 1916, he and his family had been living in Biloxi for six years. Joseph and wife Mary were living in Baltimore as early as 1900. That year, they were renting an apartment at 757 South Luzerne Avenue. Married for about three years, they had two children, Joseph, Jr. and James.

According to the 1900 and 1910 censuses, Joseph and Mary were born in Austria in the early 1870s, but were part of the Polish-speaking population. They immigrated to the US in about 1875 (Joseph) and 1885 (Mary). Starting with the 1920 census, Joseph and Mary claimed they were born in Maryland, but that is incorrect, since several credible sources indicate that they were naturalized in the early 1900s.

In 1910, they were living in Biloxi, at 384 Charles Street, in tiny quarters provided by the Biloxi Canning Company. Joseph was the caption of a schooner. By that time, they had seven children, including Marie. All of the children over seven were attending school. They were to have three more children in the next decade.

By 1920, they lived at 963 Reynoir Street, also in company housing. Marie, then 17 years old, was no longer in school. The family was still at the same address in 1930, but Marie was living at 921 Fayard Street in Biloxi, with her husband of seven years, Gustave Freche, who worked for the seafood industry. They had two children, Evelyn and Elton. Another child, Doris, had died in 1928 at the age of four months.

Marie divorced Gustave in 1937. Her mother Mary died in 1938. She married again in 1941, to Martin Sczepaniak, with whom she had no children. She divorced him in 1944, and changed her last name back to Kriss. Her father died in 1950.

Her son Elton passed way in 2003, at the age of 77. He was a retired commercial fisherman. He served in the US Navy during World War II, receiving five battle stars. He and his wife had six children. Her daughter Evelyn passed away in 2010, at the age of 86. She was a member of St. Martin Senior Citizens for many years. She completed a hemodialysis course in the 1970s, and was a pioneer in assisting her husband with his hemodialysis treatments at home. She and her husband had seven children.

Marie Kriss passed away in Biloxi on May 2, 1993, at the age 90.

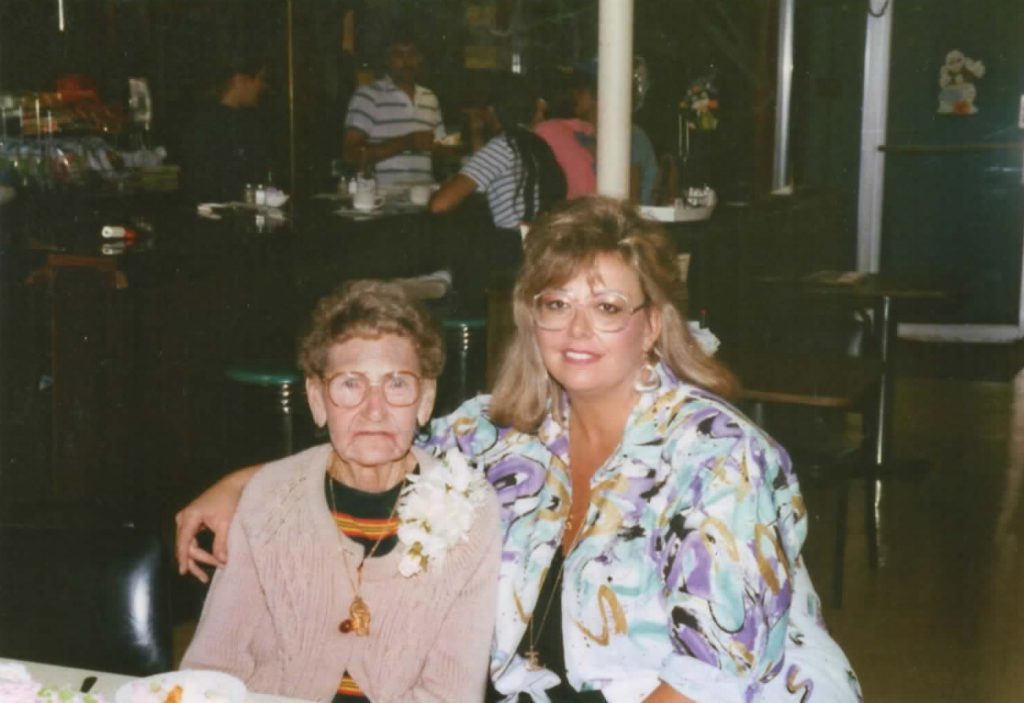

Using death records and obituaries, I located Sandra Beaugez, one of Marie’s granddaughters. She lives within a few miles of the site of the former cannery. The Hine photo of her grandmother was a complete surprise.

Edited interview with Sandra Beaugez (SB) granddaughter of Marie Kriss. Interview by Joe Manning (JM) conducted on April 21, 2016.

JM: When were you born?

SB: January 12, 1952.

JM: Where were your parents living at that time?

SB: D’Iberville, just north of Biloxi, Mississippi.

JM: What were your parents’ names?

SB: James and Evelyn Beaugez. Marie was my mother’s mother.

JM: What did you think of the photograph?

SB: It breaks my heart.

JM: Did you know that she was working as a child?

SB: Yes, I knew she was. I remember her stories of how horrible it was growing up, being so poor.

JM: Did she tell you what kind of work she had to do?

SB: Yes. She said that when they first came here from Baltimore, they came on a train. She said they had white sheets on the bed on the train, but they were so white and clean, that they didn’t sleep on them, because they didn’t want to mess them up. That was their mindset. And when they got here, she said they lived in what was called the ‘camp.’ When you lived at the camp, you worked for that particular shrimp factory that owned the camp. And when you were paid, you were paid in tokens, not money. The tokens had to be spent at the store that was owned by the factory. She said that she remembered that they would blow a whistle at 3:00 in the morning, and they had to be at work in only a few minutes. And if you weren’t there, they came and got you. She said that she remembered a lot of times that if the work wasn’t finished at the end of the day, you couldn’t go home till it was done. She remembered women being pregnant — in the family way as she called it — and they would be going into labor, but the factory wouldn’t let them go home. It was that horrible.

But she never used the term ‘horrible.’ She just called it strict or whatever. She said it would be freezing cold, and they would have to work out on the wharf. They would have these big metal cylinders that they stood in, and there was a hole to see out of, and holes to stick their hands through to pick the shrimp. The only warmth they had was a coal stove, and it was so cold, that sometimes their legs were so numb that they didn’t realize that their legs were so close to the fire that they would get blistered. They would work out there for hours and hours. She lost part of her ring finger, up to the first knuckle, from handling shrimp. The acid eventually caused it to rot away. But she never complained about it to us. She just said it was hard work.

JM: How did those stories impress you when you were young?

SB: When I was young, they were just stories. She actually still lived in what they called the camps when I was growing up, but the factories had sold them. I think there was about four of them there, and they were just little three-room shotgun houses. Just a kitchen, living room and bedroom. No bath, just an outhouse. When I used to stay overnight there, it was always fun because I didn’t realize what all that meant, until I got older. I didn’t understand then that it was horrible for her growing up. But now it just doesn’t seem real. Terrible poverty in an awful house, like it was some poor country in some other part of the world. But she never, ever complained. Never.

JM: When they finished working in Mississippi during the canning season, did she and her family go back to Baltimore?

SB: No. Once they were here, they never went back to Baltimore. They brought everything they owned.

JM: My records show she was married twice, first to Gustave Freche, with whom she had all three of her children, and then Martin Sczepaniak.

SB: Gustave wasn’t a very good husband or provider. So she divorced him and married Martin. But according to Grandma, Martin was crazy and she married him only so she could afford to support her kids. She said that he threatened once to take her son out on a boat and drown him. She divorced him, too.

Grandma was such a good woman, so generous. She would give you anything she had. Her income was very small, but she always had some savings. We would go to her and borrow money sometimes. When I went to beauty school, my father borrowed money from her to send me to beauty school. And I wound up owning a beauty shop for a long time. When she lived in public housing, everybody there loved her. All the little kids would come to her door, and she would laugh. She found humor in everything. She loved to tell jokes, and she loved Mardi Gras. I have pictures of her in costume. All her sisters were like that. They loved to have fun. They got together once a week to play cards.

But she had her stubborn streak. One time, she had her purse in the kitchen on the table, and somebody slipped in the back door and stole it. She called me, and she was hysterical. I lived only about five minutes away. The police came, but she wanted to go out herself and look for the guy, and she didn’t even know what he looked like.

She never learned to drive. When she got her water bill or light bill, she was determined to pay it right away. If she couldn’t get a ride to pay her bill, she would walk all the way to the company office.

I remember going over to her house once and realizing that she didn’t have air conditioning. I brought one over and put it in her window, but she didn’t want it. She said she had no use for it. I went over there one day, and on her table she had a bowl that had beets in it. There were all moldy. I said she should throw them away. But she just got mad, because she never threw anything away. She also never bought any clothes except underwear. The family would give her clothes, but most of the time, she just gave them away.

When she went to a hospital for the first time, she wouldn’t lie in the bed and she wouldn’t take her clothes off. She said that was only for old ladies to do. She was a very determined woman, and I guess that’s why she did as well as she did.

I was on a women’s softball team. I would take her to the games. Everyone on the team called her Grandma. She would come to our tournaments and volunteer at the concession stand and work non-stop. She once told me that she didn’t even take break to pee. And now I think about that and realize that when she was working in the cannery as a child, the boss probably didn’t let her take bathroom breaks.

We would go visit her on the weekends and stay overnight. She used to take us to the movies, but we took our own popcorn in greasy brown bags and hid them. On the way home was when the real treat began. People would leave their trash cans out on the street. She would go through them and pick out old dolls, if they looked clean. She would take off the clothes on them and make, by hand, gorgeous gowns for them. She once found a flashlight. And then she found a cowboy doll that didn’t have any legs. She stuck the cowboy in the flashlight with his head sticking out. Anything you gave her, it went on the wall. Her apartment was like a museum.

One evening, I was in New Orleans, and a bird flew out in front of my car. I couldn’t tell if I had hit it. The next day, I picked up Grandma and went to work. When we were leaving to go home, I saw this thing on my hood. She had dug the dead bird out of the grill of my car and stuck it on the hood ornament. She thought that was the funniest thing.

At work one day, she suddenly says to me, ‘I can throw my voice.’ I said, ‘Oh, Grandma!’ And she said, ‘No, I can really throw my voice. I’ve been practicing all weekend.’ So I said, ‘Okay, let me hear it.’ So she moves her mouth over to one side and says, ‘Hello, Marie.’ Of course, it didn’t work.

She loved her 11 grandchildren. Every Christmas, she would give each of them a brown paper bag with an apple, an orange, a lollipop and other candies in it. That was the highlight of our Christmas.

On Christmas Eve, I would pick her up and we would go to my Mom’s house, and later go to Midnight Mass. One time, there was a full moon. We were crossing the bridge, and out of the clear blue, she started singing ‘Silent Night,’ — excuse me, my eyes are tearing up. She had a really pretty voice, and when she stopped, she said, ‘That makes me think of my mother.’ It made me so sad. She was in her 80s then.

She was almost 91 when she died. Up until near the end, she came to work with me at the beauty shop every Monday. We would intentionally leave the garbage in the little back room, so she would have stuff to do. She really needed to feel needed. She swept my driveway with a push broom every week. She had an incredible spirit and a zest for life.

*Story published in 2016.