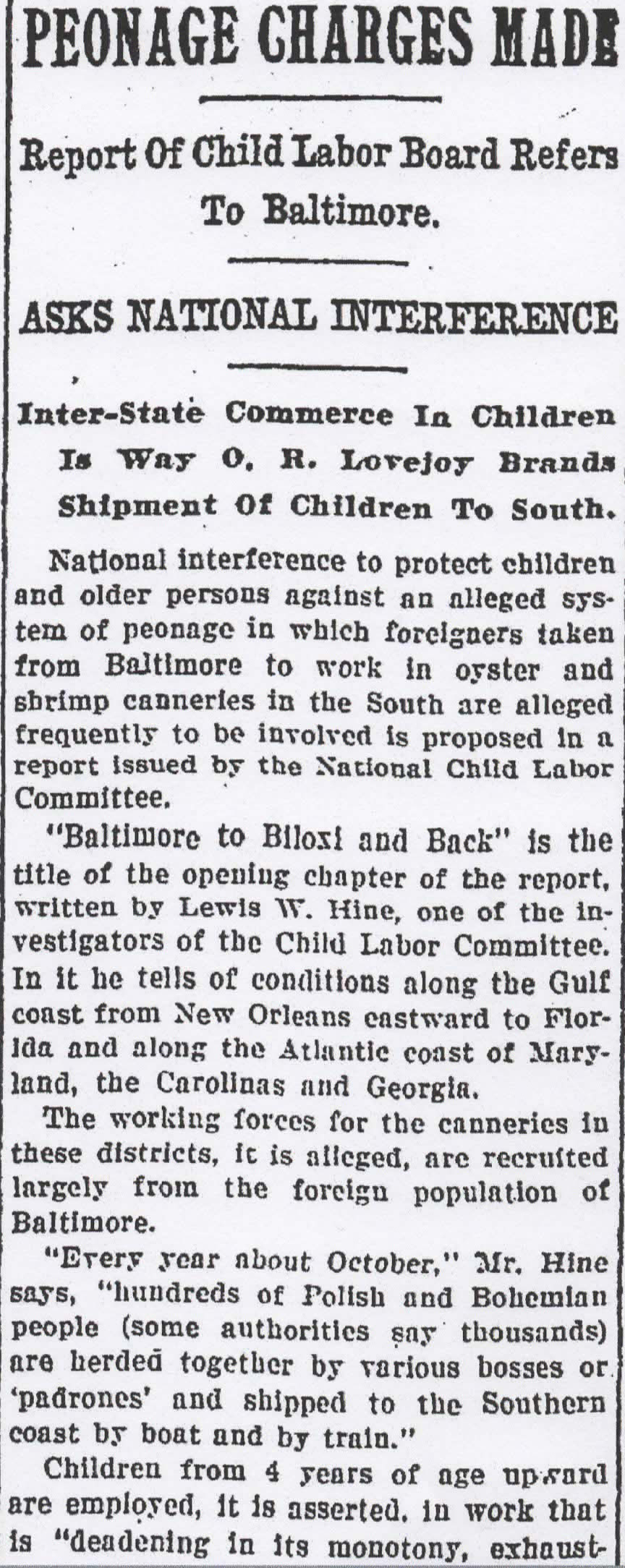

Lewis Hine caption: All are workers in a Pass Christian oyster cannery. Going home at 5 P.M. The youngest ones shuck before and after school. Two youngest are Lillie and Sadie Bilski, 8 and 6 years old. They shuck regularly. Location: Pass Christian, Mississippi, February 17, 1916.

“I remember my mother saying, ‘You’d better stay in school, or you’ll have to work as hard as I did.’ And then she would tell me how hard she worked.” –Vincent Cammarata, son of Lillian Bielski

In February of 1916, Lewis Hine took 13 photographs on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, mostly in Pass Christian, where many young children worked for companies that canned oysters and shrimp. This was his second visit. Five years earlier, in 1911, Hine had discovered unhealthy labor conditions and shabby housing for adults and children, most of them Polish-American immigrants that lived in Baltimore, Maryland, and were shipped down during the canning season. In one of his 1911 captions, he wrote:

“Mary Morris, nine year old oyster shucker, can do four or five pots a day. Shucks every day and tends the baby.”

But on this winter day five years later, Hine found that nothing had changed.

The Hine photo above, and the others taken in Pass Christian, seem to have suffered from deterioration or faulty processing. Or maybe it was just a foggy day. Whatever the cause, the picture takes on a mystical quality. In his caption, Hine writes, “The youngest ones shuck before and after school.” Maybe so, but how on earth could they have managed to learn much given the long hours and exhausting work they had to do?

According to immigration records, Piotr (Peter) Bielski, a 36-year-old Polish man from Russia, arrived at Ellis Island in New York City, on May 7, 1913. Apparently, he made his way to Baltimore quickly, where it was likely that friends or relatives from the “old country” had already settled. He probably had some kind of work lined up. He had left his wife Antonina (Anna) and seven children (including Lillian and Sadie) back home, but they came over a month later, arriving in Baltimore on June 9. Both Peter and his family had to endure the often brutal conditions of third class “steerage.”

Six months before the family arrived in Baltimore, on January 24, 1913, the following article appeared in the Baltimore Sun. Ironically, it would foretell their fate. Chances are that when their first winter in Baltimore came around, the Bielski children headed down to Mississippi.

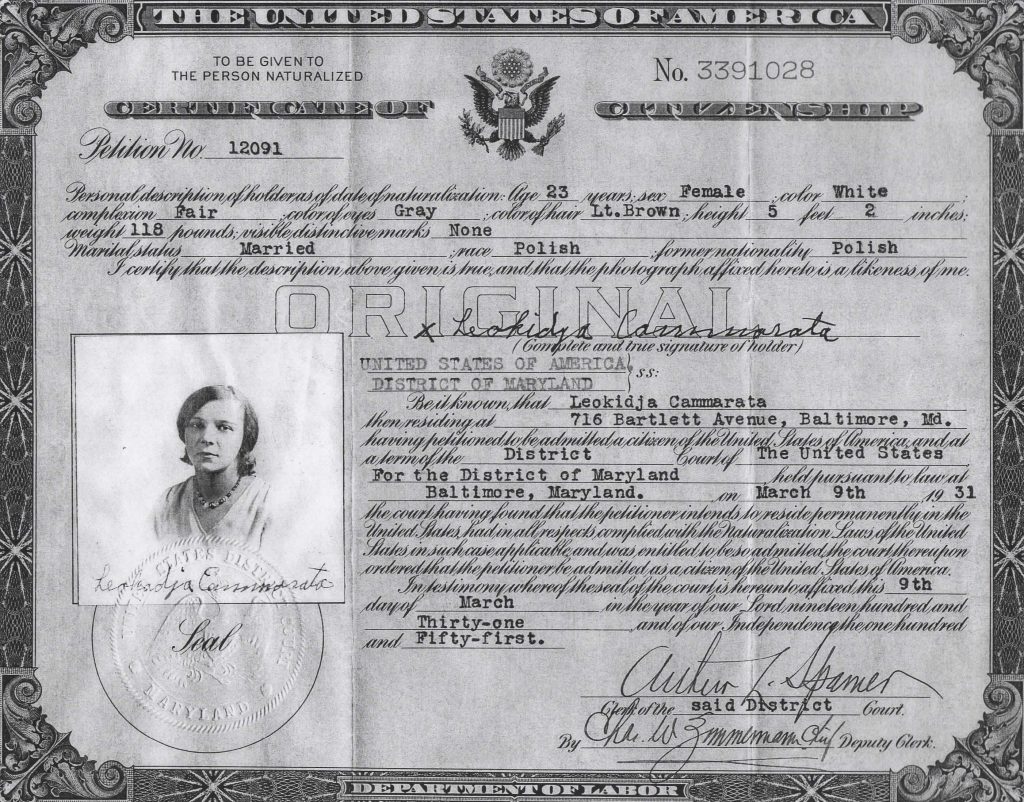

According to the census, by 1920, the family had one additional child, born in 1917. Peter was working at a coal pier, which was a facility designed for the transfer of coal between rail and ship. It was likely the Curtis Bay Coal Terminal. In 1926, Peter opened a Polish bakery. Many of his children would work there. About a year later, Lillian married Sabatino Cammarata, whose father owned an Italian bakery.

Around that time, Sadie married Frank Taska. She continued to work in her parents’ bakery. Her mother Anna died in 1939. When her father Peter died a few years later (date not confirmed), Sadie took ownership of the bakery. Oddly enough, Ida, older sister of Lillian and Sadie, married Walter Herchowski, and he started another Polish bakery.

Sadie died in 2006, at the age of 96. Lillian died a year later, at the age 99. Sister Ida died in 2006 at the age of 103. All three sisters were in the bakery business, and all three lived very long lives.

I interviewed Lillian’s son, Vincent Cammarata, and Vincent’s son Christopher. Both live in the Baltimore area.

**************************

Edited interview with Vincent Cammarata (VC), son of Lillian Bielski, and nephew of Sadie Bielski. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on January 31, 2017.

JM: What did you think of the photo of your mother and your aunt?

VC: I was overwhelmed. I have only a few old pictures of my family. Many of them were accidentally thrown out.

JM: Which of the two girls in the photo was your mother Lillian?

VC: The shorter girl. My mother was older than Sadie, but Sadie was pretty tall for her age.

JM: According to immigration records, your mother’s parents, Peter and Anna, and their children, came to Baltimore in 1913.

VC: In order to avoid World War I, which was about to break out in Europe in 1914.

JM: And according to the Baltimore directories, Peter was a laborer until at least 1923. In 1926, he was listed as owning a bakery at 2356 Foster Ave. But in 1927, he had relocated it to 801 Montfort Avenue.

VC: That sounds about right. It was a Polish bakery, and the whole family ran it. It was in the Canton section of the city.

JM: Who did your mother marry?

VC: Sabatino Cammarata. They married about 1927. They had two children, me and my older sister Delores. My father came from a little town in Sicily called Calascibetta. His family had a little money when they came over, not like my mother’s Polish family, who were very poor. His father also started a bakery in Baltimore. At first, they were selling bread from a window in their basement on Duncan Street facing Northeast Market. Eventually, my grandfather bought a place on Greenmount Avenue and opened a bakery. It was called Cammarata’s Bakery. People said it was the best Italian bakery in Baltimore. He made seven kinds of Italian bread. Later my grandfather bought the whole building, which had apartments in the upper floors. My father was the baker. It was the first and only job he ever had. I remember working in the bakery in the summer when I was out of school. I would go out on the delivery trucks with my uncles and help them, but whatever I got paid, I would have to bring it home to my mother. And she would give the money to family members when they needed it.

JM: Did your mother talk about working in the canneries in Mississippi?

VC: Quite often. She told me that she and her sister Sadie were taken out of school and sent to Mississippi to work in the winter shucking oysters in a cannery. Their parents did not go with them. Their older sister Ida, and some of the older brothers went with them and took care of them. Their father Peter had a close friend in Baltimore, and it’s possible that some of his children went down there, too. When my mother and Sadie came back to Baltimore, they also shucked oysters in a cannery on Boston Street, and in the summer picked beans and tomatoes in the fields outside of Baltimore. She said they were shipped out on trucks every day. And she talked about scrubbing floors for well-to-do people. My mother was pulled out of school when she was in the third grade.

JM: Did your mother work at her parents’ bakery, too?

VC: She would help out as needed, and she also helped out in her two sisters’ bakeries. But when she married my father, she felt she had worked enough in her life. She learned how to sew on her own, and she loved it. She was very talented and made dresses and coats for both the Polish and Italian families. She would stay up till two or three o’clock in the morning sewing. She refused to take money for her sewing other than the cost of materials. She never stopped working hard.

JM: Tell me about your Aunt Sadie.

VC: Sadie married Frank Taska. He was also Polish. When they got married, he was in the Merchant Marine. And then he was drafted into the Navy and saw action in the Pacific. So he was never home much, but he was a very fine man. When my mother’s parents died, Aunt Sadie took ownership of the bakery. She ran it while Uncle Frank was still at sea. Sadie ran the bakery most of her life. She finally sold it and built a custom home in Towson. When she died, all of her brothers were gone by then. Sadie had only one child, a son named Frank. He married twice, but had no children. He was a fine gentleman who died young at age 43.

My mother’s oldest sister, Ida, got married to Walter Herchowski when she was about 15. He was also a Polish immigrant. He also started a bakery in the Canton section of Baltimore. Ida had two children, Peggy and Walter, who eventually took over the business and retired successfully from it.

JM: That’s three bakeries that various members of the family owned. Were they in competition with one another?

VC: No, because they were in different ethnic communities. The Italians and the Polish people helped each other and got along very well.

JM: When were you born?

VC: In 1930: I grew up at 716 Bartlett Avenue. The bakery was at 2401 Greenmount Avenue, just two blocks away. We had a single-family row house with white steps. It’s still there.

JM: How far did you get in school?

VC: I graduated from the University of Maryland with a degree in mechanical engineering. I worked in various engineering jobs associated with research and development projects in aerospace. For most of my career I worked for the Army Chemical Center at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, in Aberdeen, Maryland, developing chemical agent weapons systems.

JM: Were Lillian and Sadie close?

VC: Yes, as two peas in a pod. All three girls were. My mother and father moved to Baltimore County in 1953, and later sold the bakery. Aunt Ida lived next door. When Aunt Sadie sold the business, she retired close by her sisters. They all built their custom homes. Ida died at age 103.

JM: What was Sadie like?

VC: She was a tough customer, tough in business and tough with people sometimes. She was a very smart businessperson. She ran a tight ship in regards to her household, and keeping her brothers in line. They worked in the bakery and also as stevedores. I got along with her just fine. I was her guardian when she moved to Edenwald Retirement Community in Towson. Sadie died at the age of 96.

My mother was liked by everybody, especially the Italian side. She got dementia when she was about 90. My father had died in 1989, and she could no longer live alone. She lived for a while with my sister, who was widowed at that time. We finally had to put her in a nursing home. She lived there almost 10 years.

I remember my mother saying, ‘You’d better stay in school, or you’ll have to work as hard as I did.’ And then she would tell me how hard she worked. You got paid by how many cans you filled up. You could fill them quicker if you picked out the biggest oysters. But every time she went to grab a big oyster, the older girls would smack her on the knuckles with the back of an oyster knife. She carried that cross all through her life. So did Sadie.

**************************

Edited interview with Christopher Cammarata, grandson of Lillian Bielski, and great-nephew of Sadie Bielski. Interview conducted by Joe Manning on February 22, 2017.

Manning: What do you think about the photo of Lillian and Sadie?

Cammarata: It didn’t surprise me, because I knew she worked in the canneries. But I didn’t know how deplorable the conditions were and how young my grandmother and Aunt Sadie were when they had to work like that.

Manning: Did she tell you anything about working down in Mississippi as a child?

Cammarata: When I was about the same age as she was in the picture, she told me that when she was shucking oysters, she would pick out oysters from a big pile, but the older girls and women would hit her on the back of the hand with the back of an oyster knife if she picked up a big oyster, because the bigger oysters would fill up their cans faster, and they would get more money. Even in my grandmother’s last years, she was always scratching the backs of her hands, because they never completely healed.

Manning: What was your grandmother like?

Cammarata: She was very quiet, very respectful toward everybody, and very, very generous. If she had two cents, then you had two cents. That’s amazing, because she grew up so poor. I tell people that I come from very humble beginnings.

Our family was very close, like most immigrant families. When I was growing up, I spent a lot of time over at my grandmother’s house, and I would help her around the house. We all worked in the garden. She had an orchard at her house, and I would help her with that. My family liked to do a lot of outdoor things together. We hunted a lot, we fished a lot, and we crabbed a lot.

My grandmother was an unbelievable seamstress, even in her later years. She made clothes for me, and for everyone else in the family. She taught me how to sew. She had an old black Singer. I still have it, and I still use it. When she was old and couldn’t drive, I used to take her to the materials store. It was always an interesting trip because she was a tremendous negotiator. She would buy bolts of material from a fabric warehouse, and she would negotiate the hell out of the owner. It was quite an experience.

She went through the war years, when you couldn’t buy a lot of things. A lot of people would call her a hoarder, and that the house was a mess. But when she would buy catsup or something on sale, she would buy cases of it. She canned stuff from the garden. And we picked raspberries and blackberries. All of that has had a profound impact on my brother and me. He has fruit trees, and a big garden, and he grows and cans stuff. My wife and I pretty much grow all of our food. I like to say that we either hook it, shoot it, or grow it. When I was growing up, my family would never throw anything away because just about everything had value and could be repurposed. We always repaired things. We never went out and bought something new unless we absolutely had to. We would keep fixing the car till it had finally died.

**********************

Who are the other children in the Hine photograph? He identified only Lillian and Sadie.

In my interview with Vincent Cammarata, he said:

“She (Lillian) told me that she and her sister Sadie were sent to Mississippi to work in the winter shucking oysters in a cannery. Their parents did not go with them. Their older sister Ida, and some of the older brothers went with them and took care of them. Their father Peter had a close friend in Baltimore, and it’s possible that some of his children went down there, too.”

Could some of the other children be Lillian and Sadie’s siblings? I asked both Vincent and his son Christopher about this. Both agreed that it was a strong possibility. I examined the photo closely and noticed that the girl third from the right in the back row looks strikingly like Lillian and Sadie. She also looks about three or four years older than Lillian. Ida was four years older than Lillian, so there is a good chance the girl was indeed Ida. But there is no way to be absolutely certain.

*Story published in 2017.