Lewis Hine caption: Tipple Boy, Turkey Knob Mine, MacDonald, W. Va. Witness E. N. Clopper, August 1908.

Lewis Hine created this powerful image of a young mine worker only a few months after the National Child Labor Committee sent him on his first major assignment to photograph child laborers. But he did not tell us who he was or how old he was. The Turkey Knob Mine was located in southern West Virginia, about 150 miles north of the North Carolina line.

Hine’s journey began in Ohio and Indiana in August 1908, continued in West Virginia in September and October, then again in Indiana, and finally in the Carolinas and Georgia through January 1909. For reasons I was unable to determine, he seldom identified his subjects until he visited textile mills in North and South Carolina. Perhaps it took him a while to gain the confidence to engage his young subjects in conversation, ask questions, and jot down the answers.

I had seen this photo several times after I started tracking down the lives of Hine’s child workers back in 2006, but I always passed it by in favor of children whose names were known. A few years later, I was looking at the photo on the Library of Congress website and was surprised to find the following note buried 17 lines down the page from the caption:

Note 10/2002: Patron identifies this as her grandfather, Otha Porter Martin, b. July 3, 1897. See Reference File “Hine” for correspondence from the patron.

I was unable to find the reference file mentioned. But since I now had a name to research, I got to work right away. Pretty soon, I located one of Mr. Martin’s granddaughters, Kelly Ozias. I contacted her, but she said that neither she nor her sister, Gloria Johnson, knew anything about the photo, and had no idea if the boy was in fact their grandfather. So I put the information I had in a folder called “Closed Cases.”

In July of 2017, I received the following email from Ms. Ozias:

“You contacted me about 5 years ago regarding the picture entitled “Tipple Boy” to ascertain if it was our grandfather Otha Porter Martin. At the time, I knew nothing about it. Recently, I have made contact with a cousin (Annette McClure) who was adopted out from the family as a baby. She received several pictures and papers when her birth mother (Otha’s daughter) passed away. One picture was of the tipple boy that was cut out of a newspaper. I also have a couple pictures of Grandpa Porter (that’s what he went by, not Otha) as a miner later on in his life.”

Note: From now on, I will refer to the boy as Porter Martin.

She referred me to Annette McLure, so I called her. It turned out that she was the person who had contacted the Library of Congress in 2002. She explained:

“Porter’s daughter Clara was my mother, but she put me up for adoption. I never met Porter, who was my real grandfather. But I had seen family pictures of him. And then I saw the Lewis Hine picture of him in the Charleston newspaper. It was on the front page. He looked like a little tough kid. Sure enough, it was Porter, but the paper didn’t identify him. They said the photo was in the Library of Congress. So I contacted the Library of Congress and told them who he was. Sometime later, they added his name.”

She sent me a copy of the letter she wrote to the Library of Congress. It contained valuable details about the family.

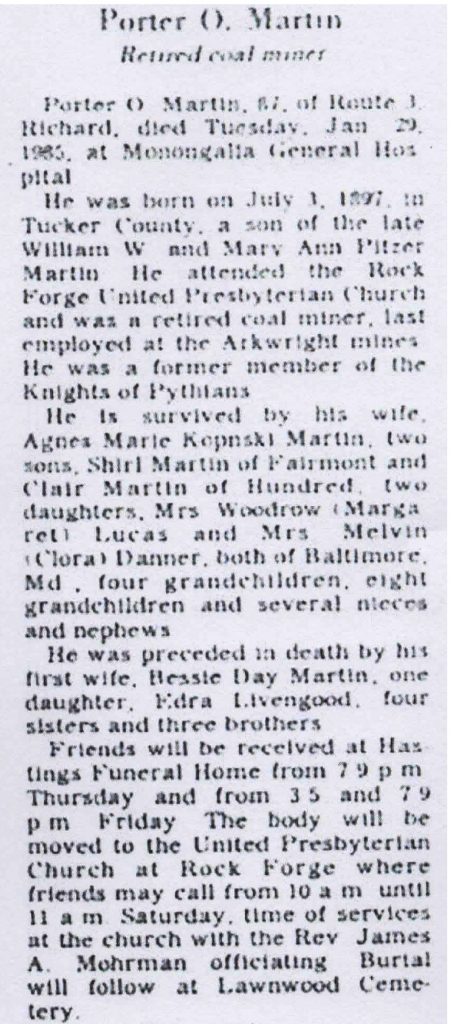

Note: In her letter, Ms. McClure states that Porter Martin lived in Cleveland in the early 1970s. That is incorrect. In the 1958 obituary of William Wade Martin (Porter’s father), Porter is listed as a survivor, and his residence is given as Cleveland. In addition, in the interview below with granddaughter Gloria Johnson, Ms. Johnson states that Porter was living in Cleveland when she was born in 1949. Also, Ms. McClure inadvertently stated that Porter Martin died on July 20, 1985. He died on January, 20, 1985.

After talking to Ms. McClure, I discovered another Lewis Hine photo of Porter in the Library of Congress collection.

Lewis Hine caption: Tipple Crew, Turkey Knob Mine, Macdonald, W. Va. Oct. 1908. Witness E. N. Clopper.

Note that the date of the first photo was August 1908, according to the caption, but the date of the second photo was October 1908. Comparing the two photos, it is obvious that both photos were taken at the same time, and in the same location (note the coal car rails). Library of Congress records indicate that Hine did not take any photos in West Virginia in August, but he took a number of photos at the Turkey Knob Mine in October. So both photos were taken in October.

Lewis Hine caption: Tipple at Turkey Knob Mine, Macdonald, W. Va. Bank Boss in center, October 2008.

A tipple boy was a worker who worked in the tipple. According to Wikipedia, a tipple was a structure used at a mine to load coal for transport, typically into railroad hopper cars. Basic coal tipples simply loaded coal into railroad cars. Tipples were initially used with mine cars. These were small hopper cars that carried the product on a mine railway out of the mine. When a mine car entered the upper level of the tipple, its contents were dumped through a chute leading to a railroad hopper car positioned on a track running beneath the tipple. Since tipple workers in Hine’s photos were wearing headlamps, it is likely that they often traveled down into the mine.

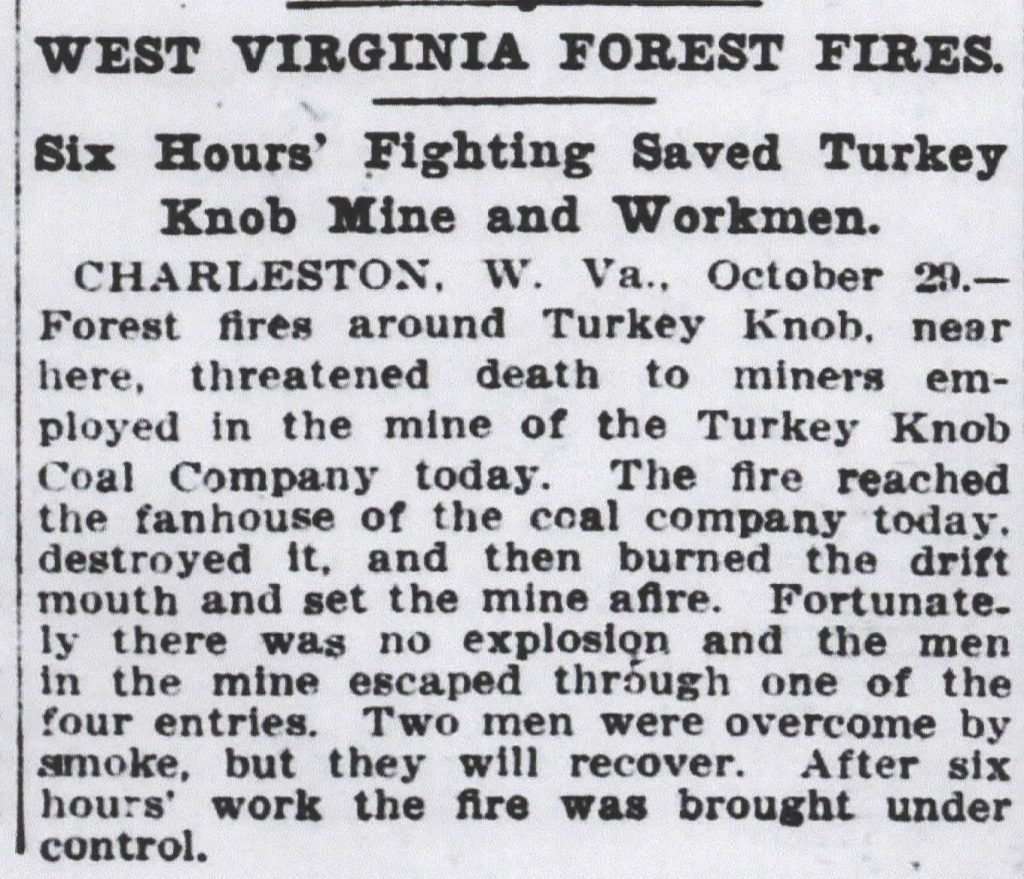

October turned out to be a scary month for Porter, his family, and his co-workers. There was a serious fire near the mine.

Otha Porter Martin was born on July 3, 1897, in Bretz, West Virginia, which is about 15 miles from Morgantown. He was the son of William Wade Martin and Mary Ann (Pitzer) Martin. I could not locate them in the 1900 census. In 1910, the family was living in Fetterman, West Virginia, about 25 miles from Morgantown. Mr. Martin was a farmer and rented the land. He may have been a tenant farmer.

Porter married Bessie Day in Junior, West Virginia, on July 23, 1918, 20 days after his 21st birthday. Bessie was 18 years old. According to his 1918 World War I registration, Porter worked for the Davis Coal Company, and he and Bessie lived in Weaver, about 60 miles south of Morgantown.

In 1920, Porter and Bessie lived in Leadsville, West Virginia, about 90 miles south of Morgantown. Porter was a loader in a mine. The census reported that he could read and write. In 1930, Porter and Bessie lived in Granville, a small community just across the Monongahela River from Morgantown. They rented their home. Porter was still a loader in a coal mine. They had five children: Clair (known as Gene) and Shirl (boys) and Clara, Edra and Margaret (girls). Bessie died on March 1, 1932, leaving Porter a widower with five children. He married about a year later, to Agnes Kopnski. The marriage produced no further children.

In 1940, Porter and Agnes rented a home in the West Virginia town of Cassville, in Monongalia County. Porter’s listed occupation was “Supply motor, coal mine,” which was probably referring to his coal delivery business. The census also stated that he got as far as the fifth grade. His 1942 draft registration listed Brandonville as his residence and “truck business for self” as his occupation. Brandonville is about 20 miles east of Morgantown. Up to this point, all of the towns Porter lived in were, and still are, tiny, unincorporated rural villages, except for Leadsville, which later grew and was renamed Elkins.

I interviewed his granddaughter, Gloria Johnson, and she filled in the remainder of the story.

Edited interview with Gloria Johnson (GJ), granddaughter of Otha Porter Martin. Interview conducted by Joe Manning (JM) on September 4, 2017.

JM: When were you born?

GJ: 1949.

JM: Which of your parents is related to Porter?

GJ: My dad, Clair Brown Martin. He was Porter’s son.

JM: When you were born, was your grandfather living close by?

GJ: No. When I was born, we lived at the old farm. Grandpa owned it. It was in Preston County, on the other side of Morgantown. It was up on the mountain. It was a fair size clapboard house. They had electric, but they had to burn coal or wood. No indoor plumbing. No indoor water. You had to walk across the driveway to get to the spring. At that time, my grandparents lived in Cleveland.

JM: Why did he live in Cleveland?

GJ: I don’t really know. There are parts of my family history that nobody talks about.

JM: Do you know when he moved to Cleveland?

GJ: All I know is that he was living there when I was born in 1949.

JM: When he was in Cleveland, was he working?

GJ: He and my grandmother were custodians at the Quimby Building. It was a big downtown office building. The owners allowed them to live in the building rent-free in an apartment that was provided for them. No one else lived in the building; the rest of the space was offices and stores. In addition to them taking care of the building, Grandma ran the elevator.

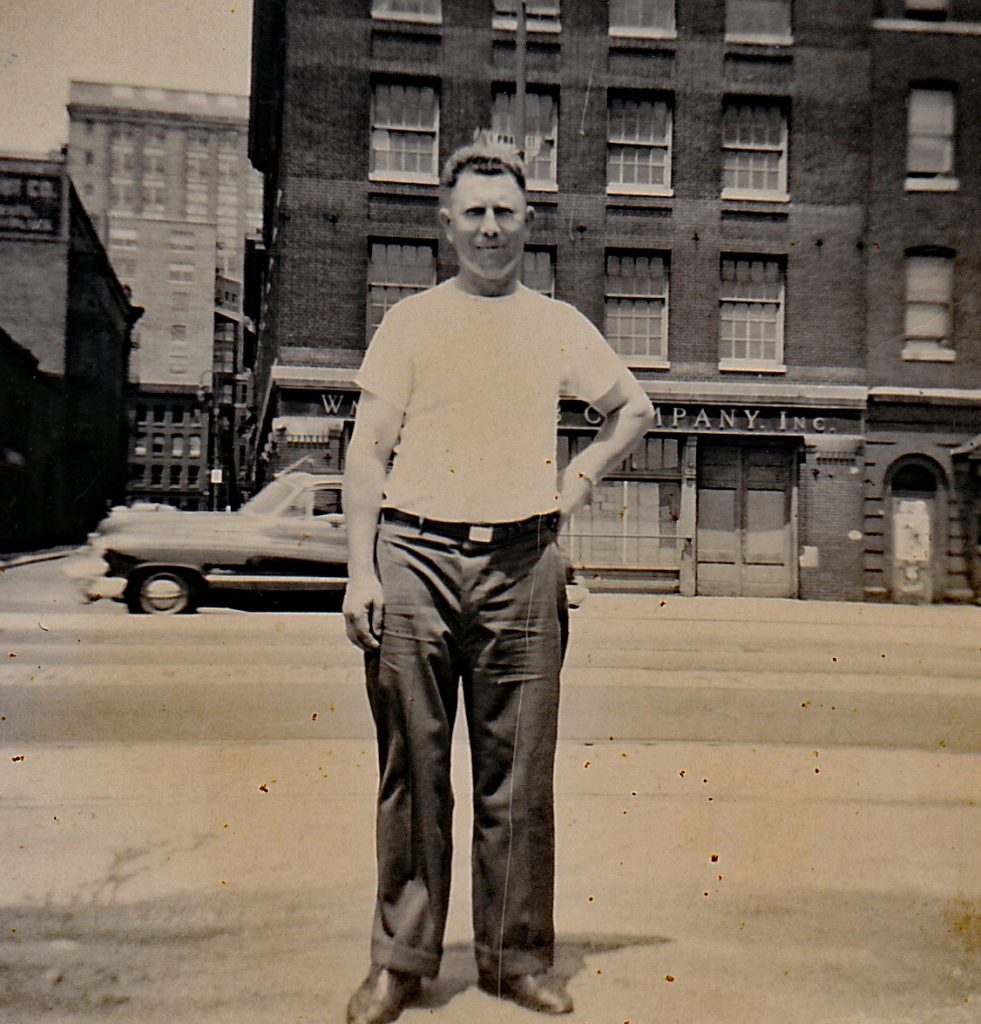

When he was young, Grandpa got into the coal deliver business. I remember his coal trucks. He was a very shrewd businessman. He wasn’t extravagant. He was very strong-willed, stubborn, much like me I’m told. West Virginia was never an easy state to live in. You worked here for less, and you worked harder for less. My grandmother taught me how to go out and forage for poke and dandelion greens.

JM: What was your grandmother’s name?

GJ: My step-grandmother, the only one I ever knew, was Agnes (Kopnski) Martin. She was from the Morgantown area. She was my grandfather’s second wife. His first wife, my real grandmother, was Bessie (Day) Martin. She died before I was born. She was the mother of all of my grandfather’s children.

JM: How many children did your grandfather and Bessie have?

GJ: Five, two boys and three girls. All of them are dead now. There was my dad, Clair, but they called him Gene. Then his brother Shirl. Then there was Clara, Edra and Margaret.

JM: Did any of the boys work in the mines?

GJ: My dad did.

JM: Did your grandfather ever talk to you about having to work in the mines when he was a boy?

GJ: He never talked to me about his childhood. But I do know that when Grandpa was young, he was a West Virginia bare-knuckle boxing champion.

JM: Was your grandfather still alive when the Lewis Hine picture was discovered?

GJ: No.

JM: What kind of a relationship did you have with your grandfather?

GJ: Very good. He and my grandmother would come down from Cleveland a lot, and sometimes, I would go up there and spend maybe a couple of months with them in the summer. When they came down here from Cleveland, they stayed at the old farm. By that time, we were no longer living there. So I would go and stay with them at the farm.

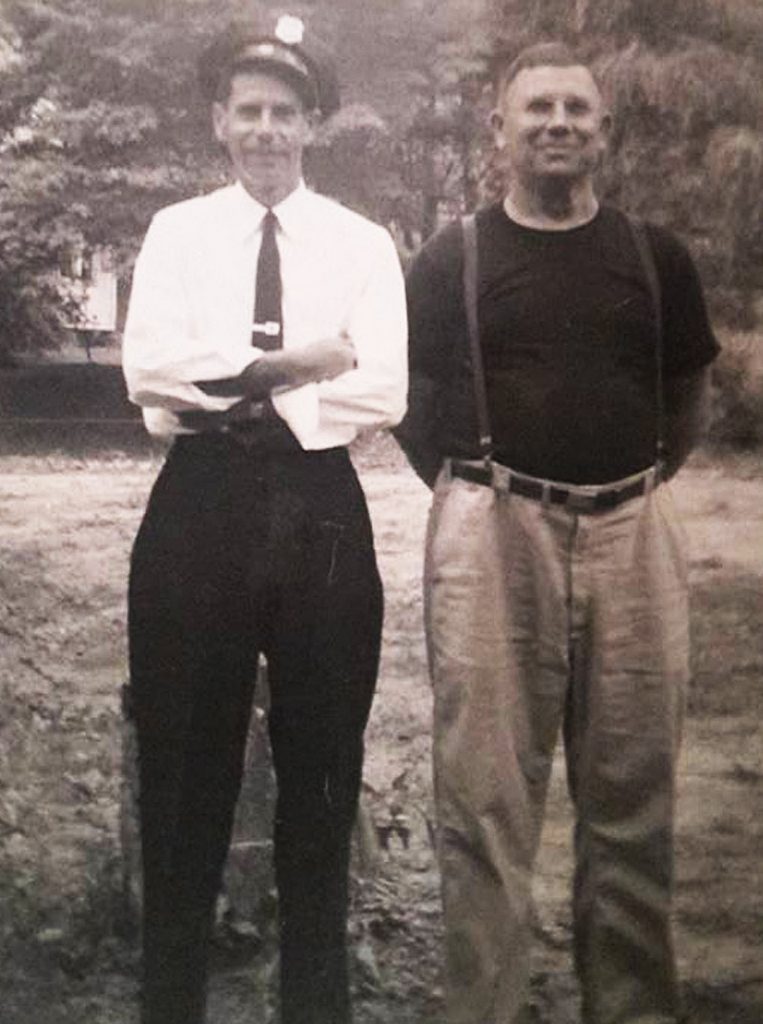

JM: What did you do when you visited him in Cleveland?

GJ: He would show me his woodworking shop at the Quimby. He was a good carpenter. He made all kinds of things. He made me a dresser and a vanity. They were beautiful. He was very kind to me, very loving, him and Grandma both. I remember that Grandpa always wore a T-shirt, Khaki pants or work pants, and suspenders. The only time I ever saw him in a suit was at my wedding. He gave me away. That made me so proud. I was 18 years old.

Later, they came back from Cleveland and bought a big house in Richard, next to Morgantown. I was older then and didn’t get to see him as often as I would have liked. I worked a great deal, and I had my family. The house was really big. Grandma had one room that she called the sitting room. You didn’t go there. Everything in that room was very old. It had antiques, ornate mirrors and beautiful furniture. I think that was the only room in the house that wasn’t cluttered.

JM: What happened to the old farm?

GJ: Out of the blue, we don’t know when, Grandpa sold it to a strip mining company. I think he must have made a great deal of money on the sale. They were living in Cleveland then.

JM: Did your grandfather give you a lot of advice?

GJ: We did have a disagreement. When I was in high school, he wanted me go to beautician school, and he offered to pay for it. I told him I wanted to be a nurse. He tried to talk me out of it, but I refused.

JM: Did he finally accept it?

GJ: Yes. He was very proud when I sent them my graduation picture. I was 34 when I graduated from nursing school. I was an LPN. I was one of the oldest students. Before that, I was an EMT and a paramedic.

JM: Do you have children?

GJ: I have two. My daughter is 48, and my son is 45.

JM: Are they interested in their family history?

GJ: Not much.

JM: Have they seen the photo of your grandfather?

GJ: Yes. They thought it was interesting. But their lives are so busy, that are just not that inquisitive.

JM: How did you react when you saw the Lewis Hine photo for the first time?

GJ: It surprised me that Grandpa went through all this, and he never said anything to us about it. What were his parents like that they would allow him to go to work in a coal mine at that age? I guess back then, times were so hard. He probably didn’t know anything else but work. It was a pathetic looking picture. It made your heart break to think that somebody that young would be forced into that kind of labor.

Grandpa loved boiled chicken wings. I remember Grandma boiling them just about every day. She fixed them in salad. And RC Cola; he bought it by the case. He wasn’t an extravagant person. He didn’t eat steak. He ate the common stuff he grew up on. He was a generous man. He was very indulgent of me. When he and Grandma would visit us on the farm, I was very young. He would stand me on the fender of his dump truck and let me pick mulberries off this huge tree. He always carried a lot of change, and he would give me pennies. He was one of the most wonderful men in the world.

*Story published in 2018