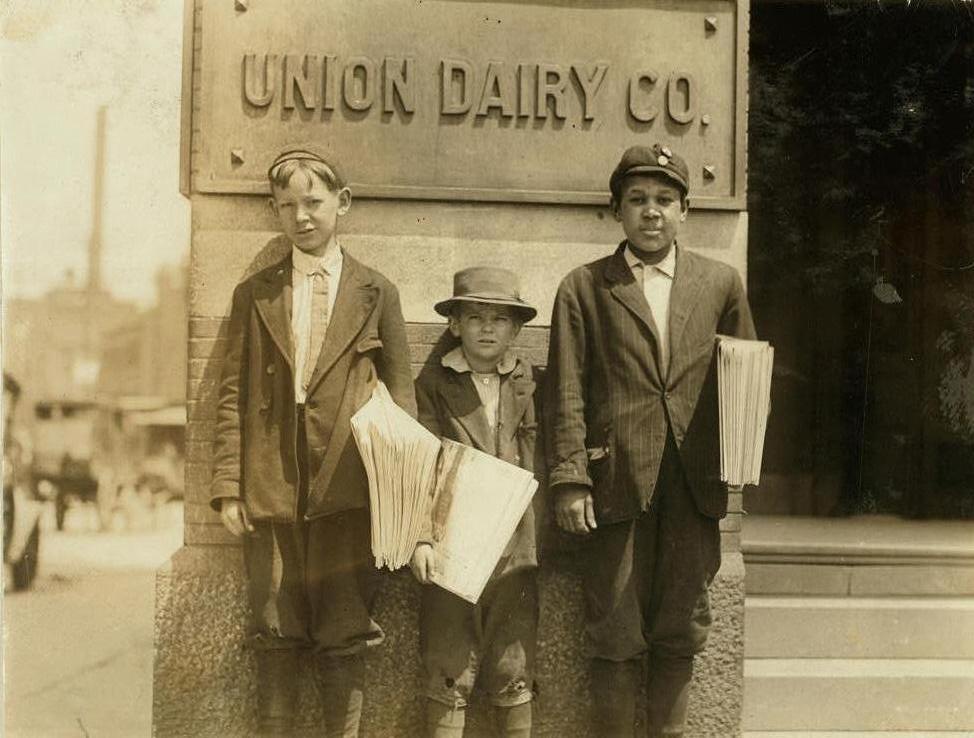

Lewis Hine caption: Truants selling papers at Jefferson & Washington 11 A.M. Monday May 9th, 1910. Smallest boy is Marvin Adams, 2637 Washington Ave. Said he got his papers “off’n de other feller.” Other boy is Owen McCormack, 2651 Washington Avenue. Location: St. Louis, Missouri.

INTRODUCTION TO STORIES ABOUT THREE ST. LOUIS NEWSBOYS

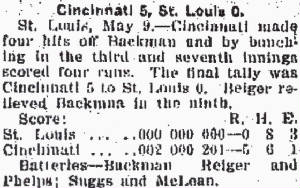

The above article appeared on May 9, 1910, the day this photograph was taken. It was published in the Hutchinson News (Kansas). A more detailed version of this game, played the day before at Robison Park in St Louis, would have appeared in both of the major St Louis newspapers at that time, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the St. Louis Times. Both newspapers can be identified in several of the 85 pictures that Lewis Hine took of newsboys in St. Louis in May of 1910.

St. Louis is well known as the Gateway to the West, called that because Lewis and Clark began their historic 1804 journey westward from the city. It was one of the largest ports on the Mississippi River, and the fourth largest city in America in the late 19th century. It hosted the World’s Fair and the Summer Olympics in 1904. It is the still the home of Anheuser Busch and the great St. Louis Cardinals, one of the most revered of all sports franchises.

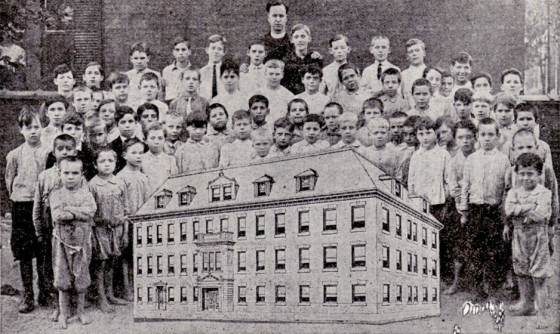

But the city is also known for its newsboys, not because Hine took so many pictures of them, but because of Father Peter Dunne’s famous News Boys Home and Protectorate, which housed orphaned newsboys. It opened in 1907, at 3010 Washington Avenue, only a half-mile from where these three boys were hawking newspapers on a sunny Monday morning in May. The popular 1948 film, Fighting Father Dunne, starring Pat O’Brien, brought Dunne’s celebrated (though romanticized) story to a wide audience. The building now houses Harbor Light Center, a substance abuse treatment center owned by the Salvation Army.

The movie helped to perpetuate the erroneous perception that most newsboys in the early 20th century were poor orphans. Studies by the National Child Labor Committee and other child advocate organizations of the time established that most newsboys had at least one parent at home, and that their families were not necessarily poor.

The photograph of the three boys is especially interesting, because the boy on the right was African American. Hine’s over 5,000 child labor photographs seldom showed non-white children, since the types of work that he investigated were performed in all-white workplaces. In the case of newsboys, it would have been uncommon for newspaper companies to use non-whites to sell to the mostly white audiences they catered to. But among Hine’s St. Louis pictures, nine included at least one African-American boy. In fact, one picture (immediately below) included eight African-American boys, none of which were the unidentified boy in the picture I am researching.

Lewis Hine caption: Truants selling papers at Jefferson and Washington 11 A.M. Monday, May 9th, 1910. Smallest boy is Marvin Adams, 2637 Washington Ave. Said he got his papers “off’n de other feller.” Location: St. Louis, Missouri.

In the caption of the first photo, the one with all three boys, gives us the home addresses of Owen and Marvin, he tells us that the boys are standing near the corner of Jefferson and Washington Avenue, and he shows us that the boys are in front of the Union Dairy Co. But he tells us nothing about the African-American boy, other than quoting Marvin as saying that he got his papers “off’n de other feller.” Apparently, Owen and Marvin did not know his name, which is not surprising, since they probably seldom engaged in social relationships with non-whites. Since Marvin got his newspapers from him, the unnamed newsboy might have been working as a bundler. Hine also tells us that the boys were truants. So on this Monday morning, their teachers would have noted their absence.

Why didn’t Hine identify the African-American boy? Did he consider him less important because of his race? I don’t think so. That would be uncharacteristic of him. It’s possible that Hine asked him what his name was, but the boy refused, presumably because he would have been wary of a white man asking such a question. I figured out right away that the African-American boy was not Owen McCormack, because Owen is listed in the census as white.

So who were these boys, and what happened to them?