Lewis Hine caption: Addie Laird, 12 years. Anemic little spinner in North Pownal Cotton Mill. Vt. Girls in mill say she is ten years. She admitted to me she was twelve; that she started during school vacation and now would “stay.” Location: North Pownal, Vermont, August 1910.

*Note: I have withheld the names, or partial names of some of Addie’s family members, in order to protect their privacy.

Chapter One: Discovering Addie And Her World

If you drive about two miles north on Route 7 from Williamstown, Massachusetts, you cross the border into Pownal, Vermont. As the road curves around to the left, there is an abrupt change in the topography. The land opens up to the Green Mountains and the vast valley formed by the Hoosic River. The road rises gently for several miles, making it feel like you are taking off in a light plane. Looking west into the valley, the uncluttered, rural landscape looks magical – a church steeple here – a barn there. You are tempted to reverse direction and turn down the road you just passed, Route 346, and see Pownal close up.

That’s when the magical becomes the melancholy. Almost immediately, it appears that the area has somehow been untouched by the celebrated economic and cultural changes of the 20th century. Except for the (mostly) paved roads, cars, telephone poles, and an occasional satellite dish, the scene looks like an old postcard, or like the Appalachia towns of Depression-era Kentucky and West Virginia.

The winding road passes a few farms and then comes to a crossroads in the village of North Pownal. The first thing you notice are the shacks and tiny houses on French Hill Road, and the badly maintained wood-frame duplexes that look like what they once were – mill housing. The mill is long gone, but it has left its legacy. By the river, there is a glass-enclosed sign on the spot once occupied by the North Pownal Manufacturing Company, a cotton mill that prospered in the 1800s and early 1900s, later becoming a tannery. It was demolished after it closed in 1988, resulting in a daunting and expensive hazardous waste cleanup project.

The sign includes a picture of the mill, and another of a young mill girl, once erroneously identified as Addie Laird, who was photographed by Lewis Wickes Hine, one of the world’s most renowned and influential documentary photographers. He referred to her in his notes as “an amemic little spinner.” From 1908 to 1917, Hine took thousands of pictures for the National Child Labor Committee, exposing the dangerous and unhealthful conditions that children endured working at textile mills, coal mines, vegetable farms, fish canneries, and as late-night “newsies” on urban streets. In 1910, Addie became what would later be one of Hine’s most famous subjects, her 12-year-old frail body leaning against a spinning machine, her tired eyes staring out as if to say, “Hey, mister, what are you gonna do about me?”

Addie’s iconic photo appeared on a US postage stamp in 1998, in a Reebok advertisement, and has hung quietly on the walls of museums for decades. One of those museums is the Bennington Museum, just up the road from Pownal. In 2002, during a special exhibit of Hine’s work, author Elizabeth Winthrop saw the photo, and subsequently wrote Counting On Grace (Random House, 2006), a haunting novel about the life of a fictional mill girl (Grace) in Pownal, who has an encounter with Hine when he takes her picture.

I met Elizabeth in the summer of 2000. She came to North Adams, Massachusetts, to begin research on Dear Mr. President: Letters from a Mill Town Girl (Winslow Press, 2001), a children’s book that was to focus on a fictional Italian-American girl named Emma, who writes to President Franklin Roosevelt during the Great Depression. I had recently moved from Torrington, Connecticut, to the Florence section of Northampton, Massachusetts, and was working on Disappearing Into North Adams (Flatiron Press, 2001), my second book about the city. Elizabeth was living in the Berkshires as a summer resident. We became good friends, frequently meeting in coffee shops to compare notes and talk about our books.

Several years later, she showed me Addie’s photo and told me about Counting On Grace, which she was just starting to write. After the book was finished in the summer of 2005, she confided that she was overwhelmed with curiosity about what the life of the real mill girl had been like, but she had been unable to find a record of anyone in Pownal named Addie Laird, or for that matter, anyone at all with the surname of Laird. She told me that when the postage stamp was created, the US Dept. of Labor had suffered the same frustration with their research.

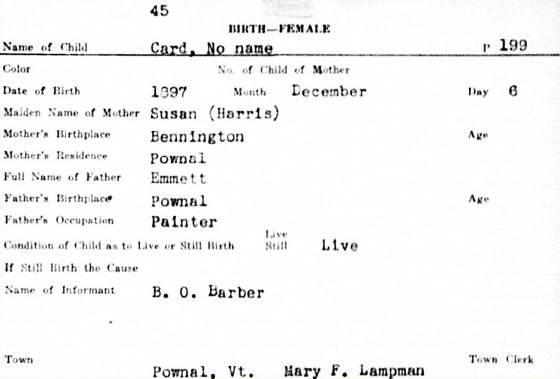

Shortly thereafter, Elizabeth made a startling discovery. By searching the US census in 1900 and 1910, at the Conte National Archives in Pittsfield, she was able to determine that although Hine had written down Laird, Addie’s correct name was Card. With this new information, she learned through town records that Addie was born in Pownal on December 6, 1897, and that she had an older sister named Annie, who also worked at the mill and later married Eli Leroy of Cohoes, New York. Annie moved to Cohoes, where she and Eli had three children.

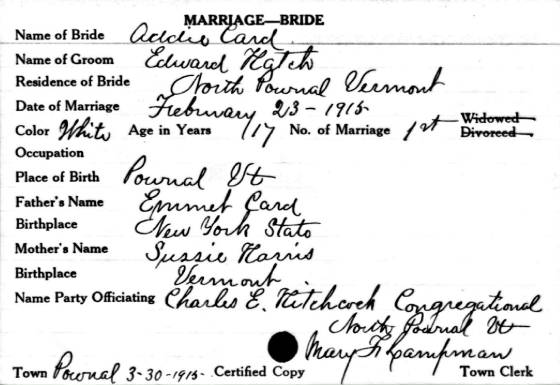

In 1900, when Addie was two years old, her mother died and her father left home, and she and Annie went to live with their grandmother in North Pownal. In 1915, Addie married fellow mill worker Edward Hatch. In the 1920 census, she is apparently childless and living with her mother-in-law, while Edward is serving in the Navy. Elizabeth could find no further records of Addie or Edward, not even in the 1930 census, which is the last one currently available to the public.

That subject came up immediately when she invited me for dinner in Williamstown, on October 17, 2005. She dropped the search for Addie in my lap and offered to hire me to find the rest of the story.

How long did she work at the mill? Did she finish school? Did she have children? How long did she live? Could she have living descendants? Had she been aware of Hine’s famous photo? That’s what Elizabeth wanted to know — and at that moment, so did I. As a historian, author and genealogist, I had experienced the excitement of the hunt and the elation of turning over the right rock at the right time. I wanted to forget dessert and just bolt out the door and start looking.

Elizabeth assigned me one special task for starters: take photos of all the gravestones of people named Card that I could find in the cemeteries in Pownal. I started my research the next morning, excited, confident, but unaware of the many serendipitous and eureka moments that were to follow.

I have a paid subscription to Ancestry.com, which has the most comprehensive data bank of genealogy information on the Web. And so before my first trip to the cemeteries, I camped out in front of my computer. Elizabeth had identified Edward Hatch’s eight siblings, including Margaret, whose married name was Harris. It occurred to me that if I could find an obituary of one of those siblings, Edward might be listed as a survivor, and I might learn where he was living at the time. While searching on some Pownal-related websites, I found a list of the names and dates of death of Pownal residents from 1921 to 1980. One of those listed was sister Margaret, who died in 1954. I called the Bennington Library and learned that it had the Bennington Banner archived on microfilm.

On October 20th, I left early on a chilly, foggy morning. Around 9:00, I entered Addie’s dreary little world. I parked at the spot along the Hoosic River where the cotton mill once stood, and where Addie’s photo stares out toward the hovels on French Hill. There’s a bench next to the sign, so I sat there and listened to the river and wondered about her life. Then I headed for the cemeteries.

When I drove into the Oak Hill Cemetery, a large one on a slope overlooking the valley, I chose to park in a small grassy space near the top, just off the winding dirt road. I got my camera and started looking. To my surprise, the first gravestones I encountered, no more than 30 feet from my car, were members of the Card family. In a total of five cemeteries, I spent the whole morning walking past rows and rows of family history, anticipating that at any moment, I might discover Addie’s grave, although there were no records of her death in Pownal. That didn’t happen.

Then I headed to Bennington. A half-hour later, I was in front of the microfiche at the library, with Margaret Harris’s obituary staring back at me. There it was, “survived by a brother, Edward Hatch, of Millerton, New York.” On the way home, I thought, “If Addie was still married to him then, she might be buried in Millerton.”

The next day, I called the only funeral home listed in Millerton. They looked up Hatch and found only one, Edward, who died December 12, 1982. He was buried at Irondale Cemetery. But his surviving widow was listed as Elvina (maiden name Goguen), not Addie. So I knew that Edward had married a second time. Had Addie died, or had her marriage ended in divorce? I called the local paper and ordered a copy of Edward’s obituary.

I went back to the 1930 census. That’s when I found Edward Hatch in Detroit, living with wife Elvina, but no children. His occupation was listed as automobile mechanic, and I figured that he had moved out there to work for General Motors or Ford. I looked up Elvina, and learned that she was born in New Brunswick, Canada, and had immigrated to Bennington in 1922.

My wife Carole and I talked about Addie all evening. Carole thought out loud: “If Addie had any children by Edward, and then died soon after, or in childbirth, the children might have been placed in the care of one of his relatives. In those days, it wouldn’t have been traditional for the father to raise them alone.” That intuitive thought turned out to be a turning point in the search.