Chapter Six: Interview With Descendants

Elizabeth Winthrop’s book, Counting On Grace, was inspired by Lewis Hine’s photograph of Addie Card, and informed by her research into the social history of Pownal, Vermont, the working conditions for children in cotton mills, and how Hine conducted his investigations. But the novel was fiction, an imagining of what Addie’s life might have been like at the time she was photographed. She didn’t even call her Addie in the book; she called her Grace. When Elizabeth completed the book, she wanted to know who the real Addie was, and how her life turned out. After uncovering a few important facts, including her correct name, she asked me to search for the rest of the story.

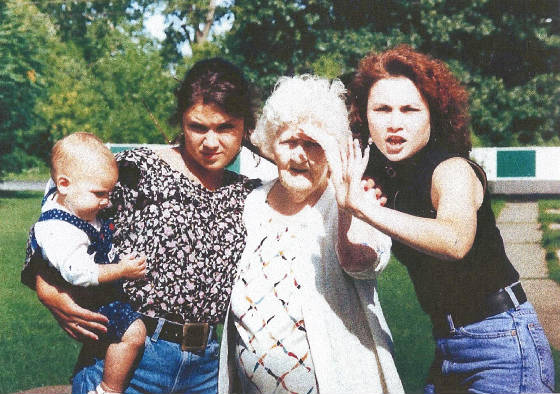

After 12 weeks of intense research and detective work, Elizabeth and I (Joe), along with my wife Carole, who had played a pivotal role in the search, traveled to upstate New York on January 7, 2006, to interview two members of Addie’s family. Both were descended from Elaine, Addie’s adopted daughter from her second marriage (to Ernest LaVigne). The two were Cathleen, who is married to Elaine’s son Robert (Bobby); and Cathleen’s daughter, Piperlea, who is Addie’s great-granddaughter. Both were very close to Addie. In the interview, they referred to her mostly as Gramma Pat. Addie unofficially changed her name to Pat as a young adult. For the sake of clarity, she is referred to only as Addie in this interview.

In the nearly three-hour conversation, spirited and often emotional, we finally learned how Addie’s life turned out, what she was like, and how she is remembered. The following is an edited version of that conversation.

Elizabeth: Addie was born in December of 1897. Her parents were Emmett Card and Susan Harris. Her death certificate says she was born on December 28, but her birth record in Pownal says it was December 6.

Piperlea: She told me she was never sure of her birth date.

Cathleen: But we celebrated her birthday on the 28th.

Elizabeth: Addie’s mother died when Addie was only two years old. Her father couldn’t, or wouldn’t take care of her, so she and her sister Annie went to live with their grandparents, Adelaide and William Harris. The grandfather died in 1908, and Adelaide remarried a man named Elijah Beagle. Addie and Annie didn’t like him, so they moved elsewhere, but I don’t know where.

Cathleen: Addie and I were talking about funerals one day, and I told her that when I was little, my grandmother died, and they laid her out in the living room. And she said, ‘That’s the way it was done back then. I can remember being a child, and they laid out my grandfather in the house, and there were candles all around him.’

Elizabeth: Addie married Edward Hatch on February 23, 1915, in the Congregational Church. She was only 17 years old. The strange thing is that her grandmother’s second husband was also Ed Hatch’s maternal grandfather. We don’t have any pictures of Edward Hatch, so we don’t know what he looked like.

Cathleen: She said he was tall, blond and handsome. She was a blond, too. She said that she didn’t have a big wedding.

Joe: On his WWI draft registration card, Ed Hatch described his build as tall.

Elizabeth: Five days after the marriage, Addie’s grandmother died, of apoplexy.

Piperlea: I remember her telling me about that.

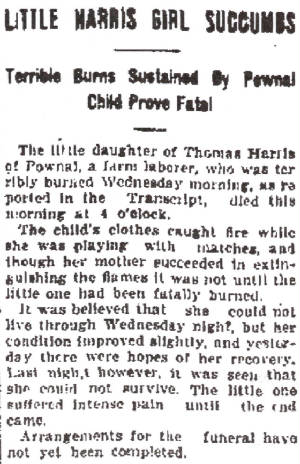

Elizabeth: Just think of her history of abandonment. Her mother died, her father left her, her grandfather died, and her cousin, Rose Harris, was burned to death at the age of three. She was playing with matches and set her clothes on fire.

Cathleen: She told me about that. She said one of her cousins set herself on fire.

Elizabeth: Her sister got married and moved away in 1914.

Cathleen: And they were very close.

Elizabeth: And then her grandmother died a year later.

Cathleen: She talked about her grandmother all the time.

Piperlea: She told me she was still working at the mill when she got married. She said that the day her grandmother died, she was working at the machines, and she looked up, and her grandmother waved to her from outside. She said, ‘I’ll be right there, Gramma.’ She looked down, finished what she was doing, looked up again, and her grandmother wasn’t there. She told her supervisor about it, and he said that he hadn’t noticed her grandmother there. She went home, and her grandmother was getting her last rites. She thought that, somehow, her grandmother was saying goodbye to her. That gave me goose bumps.

Elizabeth: Addie’s daughter, Ruth, was born on June 26, 1919. Addie was 21 years old then.

Cathleen: Addie was very small, very tiny. When Ruth grew up, she was about 6′ 1″, a huge woman. Addie told me that she got sick after Ruth was born because she had a terrible time with the birth, and that she wouldn’t be able to have any more children. She almost bled to death. She was living at the time with Ed’s mother, but Addie didn’t get along with her. She told me that she wouldn’t allow Addie to take care of Ruth, so she and Ed finally broke up, and his mother had Addie sign a paper giving her temporary custody of Ruth. But the paper she signed actually gave her permanent custody.

Elizabeth: Maybe she couldn’t read it.

Cathleen: She could read, but she wouldn’t have understood it in legal terms. So she must have been tricked. I just can’t picture her willingly abandoning her child. She told me it bothered her for years that they took Ruth away from her.

Piperlea: She told me that, too.

Joe: All the documents we have show that Ruth went to live with her Aunt Jenny Remington, Ed’s sister. She had married Louis Remington, and they lived in Bennington. Ruth was raised by them, and she regarded Jenny as her mother. When Ruth married her first husband, Thomas, in the announcement, Addie is listed as the niece of Jenny Remington, but neither Addie nor Edward are listed as the parents, nor were they listed as present at the wedding.

Elizabeth: But the marriage announcement says that there were guests at the wedding from Cohoes and Detroit. Ed Hatch was living in Detroit then, so maybe he did go to the wedding.

Cathleen: I’m thinking that if there were guests from Cohoes, Addie’s sister Annie, who lived in Cohoes, was probably the one at the wedding. I know that Addie did not go to Ruth’s wedding, but she knew about it. She also knew that Ruth had a daughter later, and that she married a second time. Addie and her second husband, Ernie (Ernest LaVigne), lived in Hoosick Falls for a while. That’s where Ernie died, in 1967. So Addie knew what was going on, Hoosick Falls being such a small town.

Elizabeth: Let me show you this. Here is Addie in the 1920 census. She’s 22, and she’s been married for five years. She is living with the Hatches, her mother-in-law Bethany, and Bethany’s children: Cornelius, Earl, Margaret, and John. Eddie was off in the Navy then. Addie is listed as a spooler. All of the kids worked in the mill, but her mother-in-law did not work. It says that Addie can read and write. The census was taken on January 16, 1920, but Ruth is not there.

Joe: Ruth was born in 1919, but the first time she showed up in the census was in 1930, when she was living with her Aunt Jenny in Bennington.

Elizabeth: Addie and Ed divorced in June of 1925. In Addie’s divorce record, she was charged by Ed with adultery, starting on the last day of December 1919, and continuing for three consecutive years. But one month later after December 1919, according to the census, Addie was still living with the Hatches. She may have been going back and forth to North Adams; we don’t really know.

Joe: There was a streetcar that went to North Adams from Pownal at that time.

Elizabeth: The divorce decree also gives Ed custody of Ruth.

Joe: For some reason, Addie did not appear at the divorce hearing. She didn’t have a chance to defend herself.

Cathleen: She probably just wanted to be rid of him. From what Addie said, Eddie’s mother hated her from the day they were married. And she told me that she had Ed arrested once. She never said anything good about him.

Joe: Eddie married his second wife, Elvina, six weeks after the divorce. He went across the border to Hoosick Falls to get married.

Cathleen: If it was only six weeks after, he must have been playing around a little himself.

Joe: He was working at the time in a mill in Bennington, and Elvina was working there, too.

Cathleen: I know that she lived with Ernie a while before they got married.

Joe: Do you know when Addie met Ernie, and when she married him?

Cathleen: When she and Ed Hatch broke up, she went to North Adams, because she had friends there, and she was staying with one of them. She met Ernie in North Adams. She went with him for about a year before they married.

Joe: My research shows that he was working at the Beaver Mill then. It was a textile mill. Addie was living on Ashland Street in 1921, according to the city directory. Where did Addie and Ernie live after they got married?

Cathleen: I believe they went to New Jersey. Ernie became a Merchant Marine. They lived in a boarding house. That’s where they adopted my future mother-in-law. There was a woman who lived in the boarding house named Mabel Brown. She had been married to a man named Brown, and she had four boys by him. She had gone out with a Portuguese sailor and got pregnant. Her husband threw her out and told her, ‘When you get rid of this baby, you can come back.’ So right after the baby was born, Addie and Ernie adopted her. I think she was maybe two or three weeks old at the most. I don’t know what her name was when she was born, but Addie and Ernie named her Elaine Mae LaVigne. She looked very Portuguese. She had black hair.

Joe: Elaine was born on October 14, 1925. When did Addie, Ernie and Elaine leave New Jersey?

Cathleen: About two or three years later, they moved to Cohoes (New York). Elaine was raised in Cohoes.

Joe: This may surprise you. In the 1928 North Adams city directory, Ernie is listed as working at the Beaver Mill, and living at 228 Beaver Street. And Addie wasn’t with him then.

Cathleen: So that probably means that she had gone back to Cohoes with Elaine, and he went to North Adams. Elaine would have been about three years old then. Ernie had a serious alcohol problem, even back then.

Joe: Where did they live in Cohoes?

Cathleen: Various places. When Elaine was growing up, they lived in some of the millhouses. Then Elaine met and married George Provost. They moved to New York City in 1945, and Addie went with them. Elaine and George had their first son, Larry, the same year.

Elizabeth: Where was Ernie?

Cathleen: He was in and out of a mental institution because of his alcohol problem. Addie had to work in some of the mills in Cohoes while she was raising Elaine. She and Ernie were separated on and off through the years. Eleven months after Larry was born, Elaine had Bobby, my husband. Then they found out that George was married to another woman, so he left, and now Elaine is in New York with Addie and the two children. Elaine worked, and Addie was raising the two kids.

Joe: Addie’s sister Annie died in 1954. In her obituary, Addie is listed as living in Brooklyn.

Cathleen: She never lived in Brooklyn. That was a mistake. When Larry was five and Bobby was four, Addie took them to Albany on a Greyhound bus. She lived on Lancaster Street. She went on the dole and lived in a boarding house owned by Mae Carlson. Addie had the children baptized at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. She raised them alone for five years, and then Elaine came back. What was going on with Elaine during that period, I don’t know. Elaine lived with Addie and the kids in Albany, on Morris Street. Elaine worked as a waitress, and Addie took care of the children. They all stayed there until Bobby was about 15, so that would be about 1961. And then Addie moved back to Cohoes. She apparently reunited with Ernie, and they moved to Hoosick Falls.

Joe: I saw the town directories for Hoosick Falls, and Addie and Ernie lived at 12 Spring Street from 1963 to 1967. She was right down the street from Ruth. Wouldn’t that have been a problem?

Cathleen: By that time, she had raised Elaine, and Bobby and Larry, her grandchildren, were almost grown up. They were her family, not Ruth. Ruth didn’t want her, so she ultimately rejected Ruth. After she broke up with Ed Hatch, she didn’t see Ruth for many years. A few years before she and Ernie moved to Hoosick Falls, Addie and I went there and tried to see Ruth. We went to the door, and I knocked. Ruth opened the door and then slammed it in my face. We went back a couple of years later, and she came out and talked for a few minutes, and then that was it. Right before Addie died, she called and talked to Ruth a couple of times, and when Addie died, Ruth and her daughter came to the wake, but they didn’t come to the funeral.

Joe: Ernie died in 1967. What happened?

Cathleen: Addie heard a noise in the bedroom and found Ernie dead on the floor next to the bed. He had been quite ill for a while.

Joe: They were together more than 40 years.

Cathleen: They were probably together only a little while during that 40 years. But she took care of him the last years of his life.

Joe: I found out that he was born in Albany. In his obituary, he has two other children listed, which I assume were from a former marriage.

Cathleen: I never heard Addie mention that he had other children. Maybe she didn’t know.

Joe: Someone had to have written that obituary, or contributed the information. It might have been Addie.

Cathleen: That’s strange, because she never brought that up. But I used to have long conversations with her, and she seldom talked about Ernie. After he died, Addie left Hoosick Falls and moved in with Elaine, in Cohoes. The next year, I got married to Bobby, and we asked Addie to move in with us. We lived in several places in Cohoes for two or three years, and then we moved to Albany, and Addie came with us. In about 1971, Addie moved back to Cohoes and lived by herself at 4 Congress Street, and then she got into a project called Saratoga Sites.

Joe: I called the Cohoes Housing Authority, and they told me that Addie moved into Saratoga Sites in January of 1974.

Cathleen: She lived at Apartment 52, which had two bedrooms. It was a nice apartment. They were low income apartments. All she had was her Social Security, I think about $370 or so then.

Elizabeth: Did she have a pension from Ernie?

Cathleen: She should have. He worked for the railroad. But she lost the papers, so she never got the pension. But she never went without, because we would always help her when she needed it. She was very independent.

Joe: How did she feel about you helping her out? Could she accept that?

Cathleen: She didn’t mind getting help from her family, but if it was from someone not related to her, she didn’t want anything to do with it. When she got sick with lung cancer, she didn’t want to go into a nursing home, so she moved in with us. Piperlea was still living with us. When she got real sick, she went to Hospice, and then she died. She had smoked two packs of cigarettes a day, but she stopped when she turned 65. She suffered from diverticulitis for many years. It’s very painful, and I’d say that in her last 10 years, she had to go the emergency room about every two months.

Joe: In her last years in Cohoes, did she have a lot of friends?

Cathleen: No, she was family, all family. She was not neighborly. She always had people around her because there was never a day that one of my children didn’t visit her or stay with her overnight. Piperlea spent a lot of time with her.

Piperlea: There was a period of time when my parents moved from Cohoes to Lansingburgh (across the river from Cohoes), and I didn’t want to go to that school district, so I lived with Addie and stayed in school in Cohoes. That was in the ninth and tenth grades.

Cathleen: My son joined the circus when he was 19. He traveled all over the country for about six years. Before that, he was living with Addie. In fact, he lived with her more than he lived with us. In her eyes, he did no wrong, and that aggravated me sometimes. I remember one time when he was about five, we were standing on her back porch. He hit this little kid in the head, and his mother started hollering. I was having a fit, but Addie said, ‘He didn’t touch that child.’ We had a regular rip-roaring argument over it. She was the same way with Piperlea.

Elizabeth: Piperlea, what was it like living with her?

Piperlea: She waited on me hand and foot. I couldn’t do anything myself. She used to have a clothes dryer in her house, but she would always hang her clothes on the line. She had angina, but she would be out there at 90 years old hanging clothes.

Elizabeth: Was she strict with you?

Cathleen: God, no. She wasn’t strict with Piperlea. She didn’t have a strict bone in her body.

Joe: Was it a blessing that you got to stay with her?

Piperlea: Absolutely. I spent every minute I could with her.

Joe: Did she give you a lot of advice?

Piperlea: Yes. I would sit and talk with her for hours and hours. I remember her telling me interesting stories about how dangerous it was to travel when she was young, always having to worry about men snatching her. She remembered one incident when she was on a bus and somebody followed her. She impressed upon me that I should be careful going places alone.

Joe: Did she tell you anything about working in the mill as a child?

Piperlea: She told me about how hard it was working in the mill, that she had to quit school in the fourth grade to go to work, about her father disowning her, and how it was so awful not to have your parents’ love.

Cathleen: She said she had to stand on a soap box, because she couldn’t reach the spindles. She had just one pair of shoes, and she would not wear her shoes to the mill, because she didn’t want to ruin them. She said that her uncle had given them to her. They were high-button shoes. She said she had one good outfit. She and Annie went to church with their grandmother every Sunday. I don’t know which church. I asked her once what denomination she was, and she said she didn’t know. She believed in God, and she prayed, but she was not a church-going person when I knew her.

Joe: Both she and Ernie were buried in Catholic cemeteries.

Cathleen: Elaine is buried right next to her. Addie paid for it.

Carole: When we found Addie’s gravestone, we didn’t know about her second family yet, and it was so moving, because it had “Gramma Pat” on it. We had no idea where Pat came from, but it was obvious that someone cared for her enough to put that on the gravestone.

Cathleen: She changed her name when she was young, but not legally. She said to me once, ‘Would you want to be named Adeline?’

Elizabeth: What did the ‘M’ stand for?

Cathleen: Mae.

Joe: Elaine died in 1984. Where was she living then?

Cathleen: Right across the way from Addie, at Saratoga Sites. In the last 15 or so years of her life, she did some wonderful community work. She was the director of the Housing Authority, and she founded the Cohoes Community Action Agency. She had emphysema real bad, but she continued to work hard, to the point where she was carrying her oxygen with her.

Joe: What did Addie like to do in her later years?

Piperlea: She watched a lot of TV.

Cathleen: She loved Lawrence Welk.

Piperlea: And she loved to watch wrestling.

Cathleen: She used to cheer them on.

Joe: What did her voice sound like?

Cathleen: Her voice was low and soft, very soothing. She talked very quietly and slowly. But she could shout, like when she was watching the wrestling.

Joe: How do you think she would have felt if she had lived another 10 years, and had walked in the post office and seen that famous stamp with her picture on it?

Cathleen: She would have been thrilled. I am sure she would’ve have remembered having her picture taken. She never mentioned it.

Joe: Did she ever go back to Pownal?

Cathleen: We went up to Pownal a couple of times to visit one of Addie’s aunts.

Elizabeth: Did she show you where she grew up?

Cathleen: Yes. The house was in North Pownal, near where the racetrack is. It was on the side of a hill. It was an old white clapboard farmhouse. It was not very big, and there wasn’t much land with it. She told me that she and Annie lived there with her grandmother, and that she went to work at the mill at the age of eight. She told me that when she was 12, she had a nervous breakdown. She was confined to bed for almost a year.

Joe: In an institution?

Cathleen: Oh no, at her gramma’s house. Back then, you didn’t just run off to a hospital.

Elizabeth: What did she mean by a nervous breakdown?

Piperlea: I remember her telling me that she had a lot of mental anguish from her father. He blamed Addie for her mother’s ultimate demise. He blamed it on the childbirth. He said it was her fault.

Elizabeth: The death record shows that she died of peritonitis, which is an infection in the abdominal cavity, sometimes caused by appendicitis.

Piperlea: But he threw the guilt on her. She told me, ‘My birth was the cause of my mother’s death, and her death was the cause of my father disowning me.’

Joe: It’s been 13 years since Addie died. What do you miss about her the most?

Cathleen: I used to talk to her every day.

Piperlea: I miss the fact that I could do no wrong in her eyes.

Cathleen: With her, none of my children could do anything wrong. I would complain to her about something one of my daughters did, and she would say, ‘It’s not her fault.’

Piperlea: One thing I remember her saying to me was, ‘You have to lather yourself in Jergens Lotion every day.’ She covered her body with it. Every time I smell Jergens, I think of her. I remember that she had this extra long couch with rounded pillows on the end. I spent every Saturday morning lying on that couch, from the time Cartoon Express started, until it ended. My husband used to have a problem with a lot of the things I ate. A lot of those things were the stuff that Addie liked to cook. She made a lot of chicken.

Cathleen: Oh, God, did she love chicken. She’d make chicken till it came out of your ears.

Piperlea: She would fry leftover chicken in a pan with butter. I used to make it, and it was delicious, but my husband would say, ‘For God’s sake, what are you eating?’ And she made a dish that was fried leftover chicken with rice and Tang. I would make that at home all the time…except for the Tang. I couldn’t stand that.

I know it’s going to sound odd to you, but I miss the shuffle of her slippers on the floor. I would visit her all the time. I would come to the door and knock, and it would take her a while to get to the door. I’d always be afraid there was something wrong. And then I’d hear the sound of her slippers, and I knew she was okay.