My caption: Frank Dwyer (boy in front row, left) was 11 years old, brother Joseph Dwyer (front row, third from left) was 14, and Henry Maul (short boy in middle, boy next to him has his hand on Henry’s head) was 14. Alton, Illinois, May 17, 1910. Photo by Lewis Hine.

Lewis Hine caption: Noon hour. These boys are all working in the Illinois Glass Co. 1) Smallest boy, Frank (?) Dwyer, 1009 1/2 E. 6 St., says he has been working here 3 months. 2) Joe Dwyer (brother) Has been working here over 2 years. 3) Henry Maul, 513 Central Ave. 4) Frank Schenk, Lives with uncle, 611 Central Ave. 5) Emil Ohley, 1012 E. 6th Street. 6) Wm. Jarett, 825 E. 5th Street. 7) Fred Metz, 707 Bloomfield Street. In addition to their telling me they worked I saw them beginning work just before 1 P.M. Photo at 12:30. Alton, Ill. May 17, 1910. Location: Alton, Illinois.

“Dad never talked about working as a boy. Once when I was a kid, I overheard him talking about the furnaces and how hot they were. I had no idea what he was talking about. Now I know.” -Rosemary Dodgen, daughter of Joseph Dwyer

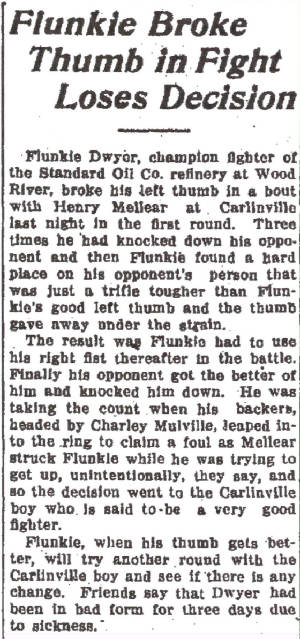

“Uncle Frank was one of a kind. He had a wonderful personality. He was a prize fighter. They called him ‘Flunkie.’ He was always smiling and pleasant, and I really thought a lot of him.” -Rosemary Dodgen, niece of Frank Dwyer

“When he was in World War I, he was gassed, and he was blind for a while. Every once in a while, he’d get this bad cough, and he thought he was going to die, and that was because of the mustard gas.” -Mary Hinton, daughter of Henry Maul

Excerpted from Child Labor, Volume 29, American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1907

The Difficulties of a Factory Inspector, by the Honorable Edgar T. Davies, Chief Factory Inspector of Illinois

“During my administration, as chief inspector, I have secured the conviction of every glass company in the state, from Galena to Cairo; and had prosecuted and convicted the Illinois Glass Company only the day before Mrs. Van der Vaart’s visit to Alton. Our inspectors had gone to Edwardsville, the county seat of Madison County, to prosecute the company; they believed they could there secure a trial along less partial lines than in Alton, the town in which the glass company in question is located. I have the court records of that trial in my hand now; $620 is the penalty imposed upon them for not complying with the child labor law. And this conviction, if you please, in the face of the fact that the Alton Glass Company is not only evasive, but constantly on the lookout. The whole town seems to be with them. The truant officer seems to be in sympathy with them; the school census was taken in the spring and the superintendent of schools never got it until many months afterward, when it was valueless, because it had been held up by the City Council.”

“It is reported that if you, a stranger, walk into the town and should resemble an inspector, the glass companies know it. Should an inspector pass a saloon or any of the stores, someone telephones; if you stop at the hotel the glass company’s officials know you are there. This glass company’s plant covers many acres; it is claimed to be the largest glass company in the world; they have a complete telephone system. This great piece of territory is all fenced in with a huge fence surmounted with barbed wire; two gates for the inspector to get in and lots of holes for the kids to get out.”

“Do you people know or realize what it means to go up against the glass companies of Illinois? Do you realize what it is to have millions of dollars invested in glass companies in the state, and to have to go up against the combined forces controlled by them? There is not a glass company in the State of Illinois, not one of them, that I have not convicted.”

“When I went into service in Illinois, as chief factory inspector, the first year of my administration the Illinois Glass Company had three hundred and seventy-seven children employed many of whom were under fourteen years of age, and there were many hundreds of children employed in the glass companies throughout the state. Is the Illinois child labor law enforced in the glass companies of Illinois? Let us see. What is the condition today: Instead of three hundred and seventy-seven children employed by the Illinois Glass Company, many of whom were under fourteen, there are now eighty children employed; all holding certificates showing them to be between fourteen and sixteen years of age; there may be some on false certificates who are under fourteen.”

Lewis Hine caption: Group of glass workers at Shop 7, Illinois Glass Co. 12:30 P.M. One of the smallest boys is Dennis White, 1013 Liberty St.,. Location: Alton, Illinois, May 1910.

I will begin with Joseph and Frank Dwyer. Henry Maul’s story will follow.

Joseph P. Dwyer was born in Alton on January 26, 1896. Francis (Frank) Herman Dwyer was also born in Alton, on October 4, 1898. Their parents were Michael and Elizabeth Dwyer, who were married about 1890. In the 1900 census, Michael was listed as working at a box factory. Michael passed away in April of 1912, just short of two years after the Hine photos were taken. In the 1920 census, Joseph and Frank were living with their mother and two younger siblings, and were working as laborers at the local Standard Oil facility. Joseph had recently served in World War I.

Joseph married Nellie Spellman on April 26, 1921. In the 1930 census, they were living in Alton with their only child, Rosemary, who was five years old. Joseph was employed as a carpenter. His mother, Elizabeth, died 10 years later. In 1954, Joseph and Nellie moved to California to be near Rosemary and her children. Joseph passed away in California on June 9, 1971, at the age of 75. Nellie remarried, and passed away in 1985.

Frank’s life was hard to track down. He married Stella Cannon in Alton on November 26, 1920. A year later, they had their only child, Fred Dwyer. Frank was a popular boxer at the time. He and Stella divorced later. According to Frank’s 1942 draft registration, he was living in Alton, and was “divorced, without dependents.” His occupation was listed as “attendant, hospitals and other institutions,” and his education was listed as grammar school only. He passed away in Illinois in October 1965, at about the age of 67. I was unable to obtain an obituary or locate any of his direct descendants, and there are no known pictures of him other than those taken by Lewis Hine.

Edited interview with Rosemary Dodgen (RD), daughter of Joseph Dwyer. Conducted by Joe Manning (JM), on January 18, 2011. Transcribed by Celeste Ramsey and edited by Manning.

JM: What did you think of the photo of your father?

RD: I knew it was him. He was skinny. That was his nickname, ‘Skinny.’ I was kind of shocked, because Dad never talked about working as a boy. Once when I was a kid, I overheard him talking about the furnaces and how hot they were. I had no idea what he was talking about. Now I know.

JM: Had you ever seen a picture of your father at that age?

RD: No.

JM: I’m going to go through some of the information I’ve already found that led me to you in the first place. In the 1900 census, your father is living with parents, Michael and Elizabeth.

RD: We called her Lizzy.

JM: Michael was about nine years older than Elizabeth.

RD: Yes.

JM: They had three kids, Anna, Joseph, and Frank.

RD: They had more later, my Uncle Bill and at least one more.

JM: Michael was working in a box factory in 1900.

RD: From what I understand, Michael had quite a temper. He was pretty hard on the kids and my grandmother.

JM: I assume you grew up in Alton.

RD: Yes.

JM: Were you aware of the glass factory there?

RD: Oh, yes.

JM: What do you think about the fact that your father was working there at a very young age?

RD: Well, it had to be very hard. My dad also went through some tough times in the war. He received a Purple Heart. He and I didn’t have a very good relationship. Now that I know that he had to work at a tender age, I feel a little guilty. Maybe I wasn’t as thoughtful as I should have been.

JM: You were born in 1925, right?

RD: Right.

JM: In the 1930 census, it looks like you were living at 339 Dry Street?

RD: Yes, I remember that house well.

JM: Did your parents own that house?

RD: No. We rented it.

JM: What was the house like?

RD: I remember how cold it was. One time, my mom put a glass of water next to her bed, and when she woke up in the morning, it was frozen.

JM: What kind of heat did you have?

RD: We had coal. In those days, coal was hard to come by, and we didn’t have a lot of money. You could buy grades of coal and, of course, we always bought the cheapest grade of coal.

JM: And it probably burned faster and at a lower temperature.

RD: My folks bought a home when I was in high school. I remember them discussing it, because Dad wasn’t too excited about it. He was worried about making the payments. Mom said, ‘Well, we can do it, Joe. It’s only $20 a month.’ That seemed to me like a lot of money. We didn’t have much, except for the $300 dollars my dad got from the war because he had been gassed. I remember he showed me the money, and he said, ‘Rosie, I want you to look at this hundred dollar bill. You may never see one again.’

JM: Did your father graduate from high school?

RD: No, but he got through grade school.

JM: What did he do for a living?

RD: When my father got out of the service, he went to Nauvoo, Illinois to learn to become a carpenter. But he loved working with numbers. He really wanted to be a CPA. That might have just been a pipe dream, you know, something he thought he wanted to do. When he first went to work, they didn’t have a job opening for a carpenter, so he took a job as a water boy. And then they hired him on as a carpenter. I remember that he worked on a dam in Alton for a few years.

JM: How big was he?

RD: He was about 5′ 9”. He wasn’t real strong, but he had a lot of determination and grit.

JM: In the 1920 census, he was listed as working as a laborer for Standard Oil.

RD: Really? I didn’t know that.

JM: And Frank was also working for Standard Oil.

RD: You’re kidding.

JM: At that point, your grandfather had been dead eight years.

RD: That’s right. I remember that they had a retarded daughter. Her name was Sissy. Grandma really had a hard life with her. When I was a kid, I was kind of afraid of Sissy. Grandma was worried about what was going to happen to Sissy when Grandma got older and couldn’t take care of her. My mom said, ‘Don’t worry about it. If anything happens to you, we’ll take Sissy.’ I thought that was kind of mind boggling, because that would change everything at home. But then I figured that somebody had to take her.

JM: In 1920, your grandmother and your father were living at 1009 Humboldt Court.

RD: The house was small. Grandma lived in the basement and had a small kitchen and bedroom.

JM: She died in 1940.

RD: I was still in school. And Sissy had already died. I remember that on payday, Dad and I would walk over to see Grandma, and he would give her five dollars.

JM: When you were young, did your father have a car?

RD: No. We walked everywhere, or we rode the bus or the streetcar. Dad had a friend that drove the streetcar, and he would ride with him. They would talk, and when he’d get at the end of the line, Dad would go out and pull the rope and put the trolley up on the other rope and away they’d go again. He would spend hours on the streetcar talking to him. My parents didn’t get a car until I was almost out of high school. It was during World War II. I remember that they had to put it in the garage for a long time because you couldn’t get rubber for tires.

JM: Did you go to the public schools?

RD: My parents were struggling, but they did put me through the Catholic high school. And that was quite expensive.

JM: Did your mother work too?

RD: She worked only when I was in high school. She worked in a café. The owner made his own candy. When I was in high school, I used to pack the candy. There were a bunch of us from the high school that did that. When my mom was working, I remember that Dad would expect dinner on Sunday, and Mom would put on her union button that she got from the store and say, ‘I’m Union. I don’t work on Sunday.’

JM: What did you do after you graduated from high school?

RD: I went to St. John’s School of Nursing, in Springfield, Illinois.

JM: Did your parents have to pay for it?

RD: No, because I went through what was called ‘cadet nursing.’ It was during the war, and the government paid our tuition and gave us $19 dollars a month. If the war had continued on when I graduated, I would have had to serve, but the war ended before I got out of school.

JM: When did you get married?

RD: The first time I got married was in 1952. I was already out here in California. I was working at the VA Hospital in Long Beach. I met a paraplegic there, and we got married. He died 10 years later.

JM: Why did you move to California?

RD: Well, I just wanted to get away from home, like a lot of kids, so I headed out to California with two other nurses, and went to work at Cedars in Hollywood, and then the VA. After my husband passed away, I remarried. He’s a wonderful husband, and we have three children. They all turned out to be nurses.

JM: Have they seen the photo of your father?

RD: Yes. It’s hanging on my wall. I am keeping them informed about what you are doing, because I want them to be up on it, and they are interested.

JM: What was Frank like?

RD: Uncle Frank was one of a kind. He wasn’t too bright. I don’t mean that unkindly. He had a wonderful personality. He was so kind. And that retarded sister of his; he used to play with her and tease her and hug her. He was the kindest person I ever knew. He married, divorced, and had one son. I remember him saying, ‘I don’t care where they bury me. They can bury me in Potter’s Field.’ And actually, that’s just about where the poor thing ended up. He went in the service after the war, but I don’t know how long he was in for. He was a prize fighter. They called him ‘Flunkie.’ He was always smiling and pleasant, and I really thought a lot of him.

JM: What did he do for a living most of his life?

RD: I’m not sure. He never had a trade, he just worked at whatever was available to him.

JM: When did your father die?

RD: He died in 1971, at the VA Hospital in Long Beach, California. He and my mother are buried at Los Angeles National Cemetery. I was 38 when I had my first child. My parents wanted to be near their grandchildren, so they moved out here in their older years. They were thrilled with the grandkids, and they took a real interest in them.

JM: I have a copy of a small article in the Alton newspaper, published on April 24, 1971. It says, ‘The 50th Wedding Anniversary of former Altonians Mr. and Mrs. Joseph P. Dwyer will be celebrated Sunday at their home at 4701 Clark Avenue, Long Beach, California.’

RD: Dad was in the hospital at the time and we celebrated it there. We had a little get-together, and it surprised him.

JM: When did your father retire?

RD: I’m not sure of the date. He was working as a carpenter at Alton State Hospital when he retired.

JM: Did your father have interests other than working?

RD: He liked baseball. He rooted for the St. Louis Cardinals. Other than that, I don’t remember anything else. He was one of those people that went to bed early – I mean, really early – and got up early. My dad was a very religious man. Every Friday evening, at 7:00, he went to the novena. He was very generous. If you needed a nickel and he had a dime, you’d get a nickel. After World War II, our house was full of, well, mostly black ladies. Dad was helping them get pensions from the war. I’d come home, and there’d be somebody in the house that he was helping. He started the Veterans of Foreign Wars in Alton.

In June 1971, when my dad was a patient at the VA Hospital, my mom and I visited him. Just before we left, I sat at the foot of the bed and looked at him, and he said, ‘Goodbye, Rosie.’ And I said, ‘Goodbye Dad.’ I wanted to kiss him, but I didn’t. By the time we got to the parking lot, Dad had thrown a blood clot and was dead.

JM: I never know when I contact somebody about a picture how it’s going to affect them.

RD: What the picture has done is to make me give my dad more respect.

Joseph Dwyer: 1896 – 1971

Frank Dwyer: 1898 – 1965

*Story published in 2011.