All of the information about this family is based on a combination of official government documents such as the US Census through 1930, marriage and death records, family history summaries posted on various genealogy-related websites, city and town directories, newspaper archives, and interviews with descendants of the family. Several of the early interviews I did helped me identify the names of the children and the married names of the girls. None of the descendants had seen the Hine photos until I contacted them.

Unfortunately, birth and death records were not officially recorded by the State of Georgia until 1919, and it wasn’t until 1928 that all counties were compliant. Before 1919, many counties did not keep reliable and complete records. Consequently some dates are approximate. Except where noted, all the photographs in this story were provided by members of the Young family. Their invaluable and heartfelt contributions are greatly appreciated.

“My mother told me about the day she and her brothers and sisters went to the orphan’s home, and how she was crying. She said she had helped with the baby all day, and then she never saw her again.” -Annie Lou Burke, daughter of Mary Young, the third oldest child in the photo of the Young family.

The story starts with the parents, Andrew Jesse Young and Catherine Bailey Young. I will follow with a story about each of their children, from oldest to youngest.

Andrew Jesse Young

“I was told that he was white headed, blue eyed, and had a light complexion. My dad was dark haired, and all of my brothers and sisters before me were brown eyed and dark haired. But when I was born, I was white headed and blue-eyed and had a light complexion. So I took after Granddaddy Young. He died when he was 37 years old.” -Clinton Willis, son of Mell Young and grandson of Andrew Jesse Young

Andrew Jesse Young was born in Gilmer County, Georgia, in July of 1870, the third of five children born to Ely (or Eli) M. Young and Elmira (or Elmiry) Young. Ely was a farmer. They lived in the Town Creek section of the county, just south of Ellijay, the county seat. Very little else is known about him.

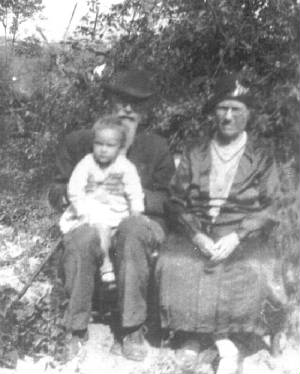

Catherine Young

“The picture of Catherine in the black dress is interesting. It looked like a widow’s dress, so I wonder if it was taken right after her husband died. She has a ring on the middle finger of her left hand, not on the ring finger. Maybe that was something commonly practiced by widows back then.” -Susan Beauchene, great-great-granddaughter of Catherine Young

Catherine Young was born Catherine M. Bailey, in Dooley County, Georgia, on August 28, 1868. Some records list 1869, including her death record. But she is listed as two years old in the 1870 census, which was counted in August, the month of her birthday; and she is listed as 12 years old in the 1880 census, which was counted in June, two months before her birthday. She was one of 12 children of Seaborn Bailey and Tobitha (Walls) Bailey, who married in 1859. Their youngest child was also named Seaborn. Mr. Bailey was a farmer. In 1880, the family was living in Lowndes County, Georgia.

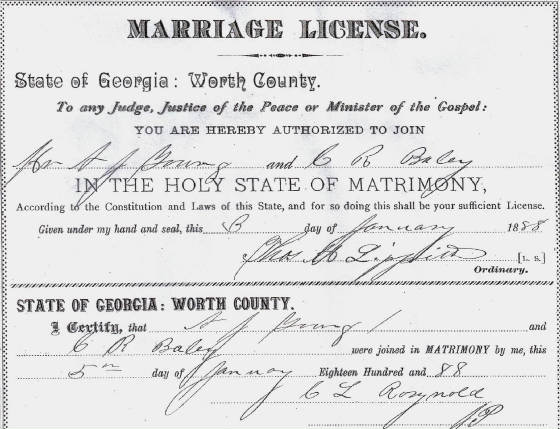

Catherine married Andrew Jesse Young (called Jesse) in Worth County, Georgia, on January 13, 1888. They had 11 known children, all born in Georgia (in order of oldest to youngest): Georgia (1888); Ella (1890); Mell, a girl (1894); Mattie, also a girl (1895); Mary (1897); Alex (1899); Eddie Lou, a girl (1900); Elzy, a boy (1902); Seaborn (1904); Elizabeth (1906); and Jesse, a boy (1907).

When Catherine and (husband-to-be) Jesse were born, Georgia was struggling with Reconstruction, which immediately followed the Civil War. White farmers could no longer depend on slavery for their labor force. By the time Catherine and Jesse married, more than a third of all farmers were sharecroppers, and Mr. and Mrs. Young would have most certainly been among them. Their situation would have likely caused them to move frequently from farm to farm, town to town, and county to county. But following their trail was not easy.

There is no 1890 census, because it was destroyed by a fire. The family does not appear in the 1900 census, but anecdotal information indicates that they may have been living in Millen, which is in Jenkins County. There was a large cotton mill there at the time where they might have worked, but according to the caption in one of the photos, Hine said that the family “had left the farm 2 years ago to work in the mill.” They probably were still sharecroppers.

Jesse died in 1907 or 1908. According to several descendants, he succumbed to tuberculosis about six months after his youngest child, also Jesse, was born. He is buried in an unmarked grave at Millen City Cemetery, now called simply Millen Cemetery.

Mrs. Young probably left for Tifton soon after her husband died, since it would have been impossible for her to work the farm. Somehow, she and her eleven children survived by relying on the earnings of many of those children, but when Georgia and Ella “went off and got married,” things got tougher. Then Lewis Hine showed up, on January 22, 1909.

At that time, the Georgia child labor law prohibited children under the age of 12 from working in mills and factories, unless the mother was a widow or disabled. If she was, then no child under the age of 10 could work. Hine documented six of the children working at the mill: Mell, Mattie, Mary, Alex, Eddie Lou and Elzy. On that date, Alex, Eddie Lou and Elzy would have been working illegally.

Exactly three months later, on April 22, 1909, Catherine brought her seven youngest children to the South Georgia Methodist Orphan Home in the Vineville section of Macon. Mell and Mattie stayed with her. No children over the age of 12 were allowed in the orphanage. It must have been a devastating event. Catherine apparently returned to her home in Tifton, hoping to get by on her wages and those of Mell and Mattie.

How did I find out the name of the orphanage?

This was one of the most important and exciting discoveries in this story. Once I established the first names of all the children, I started searching for them in the 1910 census. I wasn’t sure if the census counted children in orphanages. I started with Alex Young, who appeared to be about 10 years old. I searched for every white male living in Georgia with the last name of Young, and with a year of birth of 1899, plus or minus two years. I came up with 256 possibilities. The 107th name on the list was a boy listed as Alick Young, born in 1899. He was listed among 129 boys and girls at the South Georgia Methodist Orphan Home, in Vineville. The census was taken on April 16, 1910.

Combing through the entire list, I spotted boys Elzie, Seaborn and Jessie Young, but no girls named Young. I looked up the orphanage and found that it still existed in the same location. I called them. A very helpful staff member expressed great interest in my inquiry, and she told me that they had records of the admissions and discharges for that period of time. She also told me that girls were usually adopted quicker than boys, which might explain why I didn’t find any of the Young girls in the orphanage at the time of the census. Subsequent research would confirm that the girls had already left with adoptive or host families.

What caused Mrs. Young to make such a drastic decision?

Lewis Hine’s visit may have had something to do with it. Could he have notified the state authorities of the child labor violations and caused some of the children to be let go, resulting in a crippling loss of income for the family? I asked Tom Beck, an expert on Hine’s work, and chief curator of the Hine child labor collection at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

“Regarding Hine and reporting violations, I do not know of any instances when Hine would have gone directly to authorities to report specific deficiencies that he found. I think that word would have gotten around quickly and the next location that Hine would have approached would have greeted him with company goons to beat him senseless. On the other hand, the National Child Labor Committee’s reports were specific in citing children’s names and the factories in which they worked. So, upon seeing the reports, local authorities might have been motivated to take action, because their credibility would have been at stake. That a report would have led to further investigation that could have resulted in children being sent to an orphanage is believable.”

Several descendants of the children heard stories that the children were taken away by the county authorities, because they were not being adequately cared for due to extreme poverty. It may be that the family’s situation became increasingly desperate after the two oldest children left the home and got married, since up until that point, they may have been working full time at the mill.

It might have been Mrs. Young’s decision. At some point, she could have come to the realization that she could no longer provide for her family, and she made the only reasonable choice she had. At the time, her parents were living about 30 miles away in Turner County, but they were almost 70 years old and probably not able to take in that many children. Her late husband’s father, 71 years old, was living in Teloga, in northern Georgia, almost 300 miles from Tifton. Who else could she have turned to?

The Orphan Home

“The Orphan Home of the South Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, is located in Vineville, a beautiful suburb of the city of Macon. It was organized June 12, 1873. It has a dairy and farm for the boys, and a cutting, fitting and making department for the girls, who also take their turn at cooking and general housework. The trustees intend adding other departments as they may be able. Of course all the children attend the school of the home. This institution was first founded as a private benevolent enterprise in 1857 by Mr. Maxwell of Macon. In 1873 it passed into the hands of the South Georgia Conference. -from Georgia, Historical and Industrial (1901)

Now called The Methodist Home for Children and Youth, the facility is, according to its website: “a multi-faceted residential care home providing a continuum of specialized treatment programs that address the needs of abused, neglected and abandoned children.” It is located 104 miles north of Tifton. Mrs. Young and the children would have had a long ride on the train, which was the only reasonable transportation at the time. Perhaps a state agency or a private charity paid the cost.

The home agreed to send me copies of their records of the Young children, provided that a direct descendant of one of the children made a written request. By that time, I had contacted several descendants, one of whom agreed to make such a request. The records include the name and year of birth of each child, the dates they entered the orphanage, the name of the person or persons that brought them there, when they left, and the names of the families they left with (which helped me trace where the children went). All seven of the children are listed. Some of the names are misspelled, some of the birth years are one or two years off, and two of the children are listed twice, each with their first name in one listing, and their middle name in the other. There are also two Young children listed for which I can find no other records, nor any mention of them by the descendants.

Both of those otherwise undocumented children are listed as being brought to the home by Catherine on the same date as the others. They were Lula, born about 1900, and Bythia, born about 1905. It doesn’t appear that either of these children could have been born around the years listed unless each of them was a twin, because other children were born in those years. In his caption, Hine says: “Husband died and left her with 11 children. 2 of them went off and got married.” These two mystery children would have given Mrs. Young 13 children instead of 11.

The one called Lula was born the same year as Eddie Lou. Since several of the children were listed twice, with different names, it looks like Eddie Lou was also listed as Lula. Bythia is more complicated. Mrs. Young’s mother was named Tobitha (Bytha in the 1910 census), so it makes sense that a child would have been named after her. The only girl in the family born about 1905 or after was Elizabeth, born in 1906. I was unable to find out her middle name, so it may have been Tobitha or Bytha. Or she might have been called Beth or Bethie, and the home misspelled it Bythia. I do not believe that Mrs. Young had more than 11 children, but perhaps we will never know for sure.

Catherine married three years later (1912), to John A. Farmer (per court records in Ashburn), where several of her descendants said she went to live after she left Tifton. Mr. Farmer was previously married, and apparently widowed about 1911. He had two minor children when Catherine married him. According to the 1920 census, Catherine, unemployed and married, but separated, was living in Ashburn with her daughter Mell (oldest child in Hine photo – did not go to orphanage), who was married with two children. On the census form, Catherine’s name looks like Kettie, and so does the name of Mell’s one-year-old daughter. But in the 1930 census, the daughter is listed as Katie. So Catherine would have been called Katie also.

In the 1930 census, Catherine (Farmer), now divorced, was living in Ashburn with her 88-year-old widowed father, Seaborn Young. She was unemployed. Records indicate that she soon reclaimed her last name of Young, and kept that name the rest of her life. Former husband John Farmer died in 1942.

Through interviews with descendants, I learned that Catherine visited two of daughter Ella’s children in Alabama after Ella passed away in 1948 (Ella was one of the two children not in the Hine photo). Catherine remained close to Mell all of her life, following her when she moved to nearby Albany about 1946. Mell apparently kept in contact with sister Georgia (oldest child – not in Hine photo), who died in 1924, so Catherine probably did as well. At one point, she lived with Mell’s daughter Katie. Catherine was also close to Mattie (did not go to orphanage), until she moved to California about 1943, though Mattie returned to visit her mother at least once.

But what about the seven children who were left at the orphanage? Catherine apparently lived for a while on an allotment provided by son Alex, who served in the armed forces for a number of years. But no one was sure whether he kept in contact with his mother. She saw Eddie Lou several times, and she apparently lived briefly with Seaborn on his farm in Worth County. She visited Mary several times, but hadn’t seen her in almost 40 years when she made her first visit. There is no evidence that she communicated with Elzy or Elizabeth. Catherine’s youngest child, son Jesse, lived with her for about a year in 1928 or 1929, before moving to Orlando, Florida.

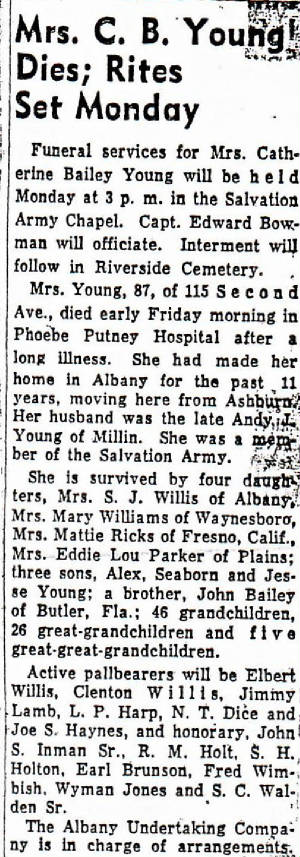

Catherine Young died in Albany on March 8, 1957, at the age of 87, according to her death records and obituary, but she was probably 88. She is buried in Albany at Riverside Cemetery. All of her living children were listed in her obituary except Elizabeth. We will learn more about Catherine in the stories that follow about each of her 11 children, and the interviews with descendants. I begin with the oldest child, one of two that did not appear in the photographs.

Chapter Five: Georgia and Ella Young, the girls that had married and left home